Catherine of Bosnia

| Catherine of Bosnia | |

|---|---|

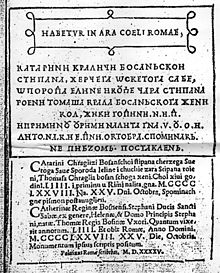

Ledger stone to Queen Catherine of Bosnia, depicting queen on a chest tomb, surrounded by the arms of her husband and father, in form of tomb effigy in shallow relief and ledger line. (reproduction from 1677)[1] | |

| Queen consort of Bosnia | |

| Tenure | May 1446 – 10 July 1461 |

| Born | 1424/1425 Blagaj, Kingdom of Bosnia |

| Died | (aged 53–54) Rome, Papal States |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Stephen Thomas of Bosnia |

| Issue | |

| House | Kosača (paternally) Kotromanić (by marriage) |

| Father | Stjepan Vukčić Kosača |

| Mother | Jelena Balšić |

| Religion | Roman Catholic, convert from Bosnian Church |

Catherine of Bosnia (Serbo-Croatian: Katarina Kosača/Катарина Косача; 1424/1425 – 25 October 1478) was Queen of Bosnia as the wife of King Thomas, the penultimate Bosnian sovereign. She was born into the powerful House of Kosača, staunch supporters of the Bosnian Church. Her marriage in 1446 was arranged to bring peace between the King and her father, Stjepan Vukčić. The queenship of Catherine, who at that point converted to Roman Catholicism, was marked with an energetic construction of churches throughout the country.

Following her husband's death in 1461, Catherine's role receded to that of queen dowager at the court of her stepson, King Stephen Tomašević. Two years later, forces of the Ottoman Empire led by Mehmed the Conqueror invaded Bosnia and put an end to the independent kingdom. Catherine's stepson was executed, while Sigismund and Catherine, her son and daughter by Thomas, were captured and taken to Constantinople, where they converted to Islam. Queen Catherine escaped, taking refuge in Dubrovnik and eventually settling in Rome, where she received a pension from the papacy. From Rome she strove to be reunited with her children. Her efforts to negotiate and offer a ransom proved futile. She died a Franciscan tertiary in Rome, having named the papacy guardians of Bosnia and her children heirs to the throne, should they ever return to Christianity.

Queen Catherine remains one of the most important figures in the folk tradition and history of Bosnia and Herzegovina. She has long been venerated by the Catholics of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and is increasingly seen as an important transethnic state symbol.

Youth

Catherine was the daughter of Stjepan Vukčić Kosača, Grand Duke of Bosnia and Duke of Hum and Primorje, Knyaz of Drina, usually considered by historiography to be the most powerful figurehead of his contemporaries amongst the Bosnian nobility. His domain later came to be known as Herzegovina, after the German title of herzog, which he later adopted in relation to the Humska Zemlja (transl. Land of Hum). Catherine's mother was Jelena Balšić, daughter of Zeta's lord Balša III and Mara Thopia of Albania. Jelena was the first of Stjepan's three wives. Catherine was the couple's first child[2] but the precise date of her birth is not known;[3] both 1424[4] and late August 1425[5] have been suggested by her biographers. It can be surmised that the place of her birth was either the Sokol Fortress, one of the residential fortresses of the House of Kosača, or the feudal town of Blagaj, Stjepan's favourite residence.[2]

Little is known about Catherine's premarital life. The earliest source that mentions her is the will of her maternal great-grandmother Jelena Lazarević, dated 25 November 1442, in which she left her her gold earrings and a snake-shaped bracelet.[2] Stjepan was a member and significant supporter of the Bosnian Church, while her mother was an Eastern Orthodox Christian; Catherine was raised in her father's confession.[6]

Catherine comes into focus following the accession of Stephen Thomas to the Bosnian throne in 1443. Thomas, of illegitimate birth but designated as heir by Tvrtko II, belonged to the Bosnian Church and was married according to its customs. His wife, Vojača, was the mother of his son, Stephen Tomašević. Two years after his accession, King Thomas abandoned the Bosnian "heresy" and converted to Roman Catholicism. The Catholic Church did not recognize his union with Vojača as a valid marriage, and Pope Eugene IV gave him permission to repudiate her in early 1445. The civil war between the King and Catherine's father, which had been raging since the former's enthronement, ended soon afterwards. Peace was to be sealed with the marriage of King Thomas and Catherine, a great honour to her father.[3] The project may have been envisioned as early as the beginning of 1445, when Thomas requested the annulment of his union with Vojača.[7]

Marriage

The marriage ceremony was conducted according to the Catholic rite[7] between 19 May, when Catherine arrived in Milodraž near Fojnica accompanied by her father, and 22 May 1446.[8] The wedding was attended by a delegation from the Republic of Ragusa (Dubrovnik), but it failed to end all internal strife, since leading noblemen such as Ivaniš Pavlović (Catherine's first cousin, lord of eastern Bosnia) and Petar Vojsalić (lord of Donji Kraji) snubbed it. The coronation, planned to take place in Mile near Visoko immediately after the wedding, was apparently postponed.[9] The new queen consort converted to Catholicism ("laid aside Patarin errors"), likely prior to her marriage,[7] and was allowed by Pope Eugene to choose for herself two chaplains from among Bosnian Franciscans.[10] The Queen's father appears to have contemplated converting too, but eventually gave up the idea and remained an adherent of the Bosnian Church until his death.[7]

Catherine proved to be a zealous convert.[6] She initiated and financed from her dowry the construction of churches throughout Bosnia, starting with one in Kupres in 1447, followed by churches in Krupa na Vrbasu and Jezero; a church in Jajce was built in 1458. In December 1458 she wrote to Pope Pius II to request that the church in Jajce, built along with a Franciscan monastery and a vicariate, be named after her namesake, Saint Catherine of Alexandria. Pius conceded her request in a bull issued on 13 December, granting absolution to anyone who visited Queen Catherine's church at Christmas or Easter, or on certain feast days. Another church built by Queen Catherine in Jajce and dedicated to Saint Catherine was a simple royal chapel. The churches built in Vrbanja, Vranduk, Tešanj and Vrila are attributed to both Catherine and her husband.[11]

The royal couple had at least two children together. In 1449, the King notified Ragusa of the birth of a son: this is likely to have been Sigismund. A daughter named Catherine was born in 1453.[12] Queen Catherine may have also been the mother of a third son of King Thomas, who was buried on Meleda. Mavro Orbini, a 16th-century Ragusan chronicler, believed that the boy was born to Vojača.[13] If Catherine hoped that her stepson's marriage to Maria of Serbia and his subsequent accession to the Serbian throne in 1459 would pave way for her own son's accession in Bosnia, the hopes were dashed very quickly: within three months Stephen Tomašević lost the Despotate of Serbia to the Ottomans and returned to the Bosnian royal court with his wife.[14]

Widowhood

King Thomas died in the summer of 1461, leaving Catherine a 37-year-old widow with two minor children. Her stepson, Stephen Tomašević, ascended the throne as intended.[10] Catherine's relations with him were poor during Thomas's lifetime; this now threatened to weaken the kingdom against its adversaries, most of all the rapidly expanding Ottoman Empire. Stephen Tomašević was thus determined to settle his differences with Catherine[15] and guaranteed her the title and privileges of a queen dowager.[10] Having assured himself of Stephen Tomašević's "affection" for his daughter, the Grand Duke refrained from disputing the succession and claiming the crown for his grandson by Catherine. On 1 December, the Grand Duke wrote to Venetian officials that the new King had "taken her as his mother",[15] Vojača having already died.[15] Although popularly believed to have retired to the castle of Kozograd above Fojnica as dowager, there is no historical basis for dismissing the possibility that she remained at the royal court in Jajce as the mother of Stephen Tomašević's closest heirs.[16]

In 1462, Catherine's situation worsened. Her brother Vladislav revolted against their father and sought help from the Ottomans. The Grand Duke and the King started preparing defenses, but the latter made a fatal mistake by provoking the powerful enemy further and then relying on the help of Christendom. In the spring of 1463, the Ottoman sultan Mehmed the Conqueror and his army started marching towards Bosnia. Catherine, who is thought to have been on her way south to visit her feuding family, immediately hastened back home.[16][17]

By May, fortresses were rapidly falling to the Ottomans. The royal family appears to have decided to disperse from Jajce and flee towards Croatia and the coast in several directions to confuse and mislead the invaders.[16] Catherine found herself besieged in Kozograd Castle, while her children were captured in the town of Zvečaj and taken to Mehmed's capital of Constantinople. Her stepson was deceived into surrendering in Ključ, from where he ordered all his castellans to surrender the fortresses, but Kozograd defied the King's order.[18] Its defenders appear to have stalled the Ottomans while Catherine escaped. Vladislav was informed by the Ragusans on 23 May that they would send vessels for his sister if she succeeded in reaching the coast.[19] Two days later, her stepson was executed on Mehmed's orders. The Queen rode to Konjic and from there probably towards Drijeva, before finally embarking on the promised vessels in Ston and sailing to Lopud, an island held by the Republic of Ragusa.[20] The two queens, Catherine and Maria, were the only members of the royal family to escape the Ottomans.[16]

Refuge in Dubrovnik

Catherine arrived on Lopud in the second half of June 1463. The Ragusan authorities, concerned that harbouring the Queen might provoke an Ottoman attack on their own state, refused her entry into Dubrovnik itself until 23 July, after her father and brothers launched a successful counter-attack against the Ottomans and pushed them away from the Ragusan borders. Her widowed stepdaughter-in-law, Queen Maria, was also denied access to the Ragusan islands until July. In Dubrovnik, Queen Catherine attempted to claim the tribute of Ston, paid annually to Bosnian rulers, but the authorities declined on 20 August. Moreover, they decided that the annual rent for the use of houses and land belonging to the Bosnian royal family should be kept in their own treasury until the legal heir could be established. On 26 October, Catherine entrusted Ragusa with Thomas's silver sword, stipulating that it should be handed over to Sigismund "should he ever be freed"; or else to nobody but the person she would name as heir. Soon afterwards she left Dubrovnik for Slano.[21] A reason for Ragusa's reluctance to comply with Catherine's demands may have been the reconquest of parts of Bosnia by the Hungarian king Matthias Corvinus, Ragusa's overlord, who attempted to revive the Bosnian kingdom by installing puppet kings.[22]

The Kosačas liberated almost all of their land during the autumn of 1463, and even succeeded in occupying some of the former royal domain.[23] Catherine likely headed towards her family's holdings, which were again under Ottoman attack in the summer of 1465. Catherine and Vladislav retreated to the peninsula of Pelješac until Ragusa granted them refuge on one of their islands.[24] Catherine left Ragusa permanently in September 1465, but her subsequent whereabouts can only be conjectured. She likely lived in Zachlumia or in the area of Šibenik. The Grand Duke, her father, died in 1466.[25]

Roman pension

In 1467, Catherine sailed towards the Italian Peninsula, possibly at the suggestion of the Veronese humanist Leonardo Montagna, who dedicated two poems to her. She took her own vessel and disembarked in Ancona.[27] By 29 October 1467, the Queen was in Rome,[27] already receiving a very generous pension from the Papal State.[28] Upon arrival, she rented a house for herself and her entourage, consisting of Bosnian nobility who had followed her. On 1 October 1469, she moved to the rione of Pigna, into a house near San Marco Evangelista al Campidoglio.[29] Pope Sixtus IV gave her considerable property adjacent to the Tiber.[30]

The Queen was a prominent figure in Roman society. Her presence at the proxy wedding of Grand Prince Ivan III of Russia and the Byzantine princess Sophia Palaiologina in 1472 was widely noted, as was her pilgrimage to L'Aquila on the occasion of the translation of Bernardino of Siena's relics to a new church (the construction of which was funded, among others, by King Thomas). That she lived a comfortable life can be deduced from the impression she left on Roman chroniclers, who wrote about the entourage of 40 mounted knights accompanying her on a pilgrimage to St. Peter's Basilica to celebrate the new year 1475.[30]

Despite the honours and financial security she enjoyed, Catherine was preoccupied with reuniting with her children. Intent on finding a proxy for negotiations with the Sublime Porte, as well as obtaining resources for their release, she turned to Ludovico III Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua, on 23 July 1470.[31] On 11 February 1474, she addressed a letter to the Duke of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, asking him to help her reach the Ottoman border and enter negotiations.[32] Sforza obliged. In the summer of 1474, the Queen was in Novi, a city in her family's possession. She was accompanied by her brother Vlatko's wife, Margarita Marzano, and probably wanted Vlatko's help in establishing contact with their younger half-brother, Hersekzade Ahmed Pasha, who had converted to Islam and become an Ottoman statesman. Whether she succeeded in that endeavor is not clear, but in any case she failed to reunite with either of her children. They both followed in their uncle's footsteps, becoming Muslims and, in Sigismund's case, also attaining high-ranking posts in the Ottoman Empire.[31]

Death and burial

Disappointed at the failure, Catherine returned to Rome and entered the Secular Franciscan Order, probably inspired by a monk at the Basilica of Santa Maria in Ara Coeli. Shortly before her death, in 1478, Catherine was visited by Nicholas of Ilok, the puppet king of Hungarian-controlled parts of Bosnia. He proposed that she recognize him as legitimate king and attempted to win her favor for several days. Nicholas recorded that the ailing Queen became "so infuriated that she looked like a sharp sabre".[33]

On 20 October 1478, Catherine made her last will, recorded by a Dalmatian priest, in the presence of seven witnesses, six of whom were Franciscans of Ara Coeli. She expressed a wish to be buried before the main altar of Ara Coeli. Considering herself entitled to dispose of the Bosnian crown, she named Pope Sixtus IV and his successors guardians of the kingdom, obligating them to enthrone her son should he convert back to Christianity or else her daughter should she reconvert. Most of her personal belongings were inherited by her courtiers. Her chapel inventory was left to Saint Jerome's Church for the Slavic Nation, while the saint's relics were to be passed to Saint Mary's Church in Jajce. She decreed that, if her son never returned to the Christian faith, King Thomas's silver sword left in Dubrovnik for safekeeping should be handed to her nephew by Vladislav, Balša Hercegović.[33] The Queen died five days after composing the will, which was immediately taken to the Pope along with her husband's sword and spurs.[33][34]

Catherine was buried according to her wishes, but her tombstone was moved from the floor to a wall of Ara Coeli during works on the interior of the church in 1590.[35][1] The original epitaph was destroyed at that time, but the Roman calligrapher Giovanni Battista Palatino had recorded it in 1545 and published two years later. It was uniquely bilingual and digraphic, written both in Latin language and script and in Bosnian language and Cyrillic. Only the Latin epitaph was restored, and can be found on her tombstone today.[1]

Legacy

Along with the 12th-century Ban Kulin, Queen Catherine is one of the two princely personages who entered Bosnian folk tradition.[36] As such, she is traditionally referred to as "the last queen of Bosnia" – erroneously, as her stepdaughter-in-law both replaced her as queen and outlived her.[37] The cult of Queen Catherine, who was first mentioned as beatified in the Paris-published Martyrologium franciscanum in 1638,[33] originated in the Franciscan province of Bosna Argentina during the Ottoman rule. Following the Ottoman conquest, a majority of Bosnians converted to Orthodoxy or Islam, and the Franciscans started promoting Catherine as a symbol of Bosnia's statehood and of its pre-Ottoman Catholic identity.[38] This is particularly evident in Central Bosnia, where folk tradition concerning Catherine is most vivid.[39]

The life of Queen Catherine has been one of the most popular themes in the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina, attracting the attention of scholars from the neighbouring countries of Croatia and Serbia as well. With the rise of ethnic nationalism, historians attempted to ascribe to her a particular national identity – Croat, Serb or Bosniak, which is completely anachronistic to medieval times.[38]

Due to her association with both of its eponymous historical regions, as well as her personal and close familial ties to Catholicism, Eastern Orthodoxy, Bosnian Christianity and Islam, Queen Catherine is increasingly becoming an important state symbol in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The anniversary of her death attracts more attention each year and is now marked with a "Mass for the Homeland". Schools, community centers, institutions and various associations are being named after the Queen. An official delegation of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina laid a wreath at her tomb for the first time in 2014. Moreover, Catherine is becoming a transethnic symbol, although mainly between Catholic Croats and Muslim Bosniaks. Both groups tend to claim her as exclusively their own, as is the case with the rest of Bosnian medieval history. The political and religious leaders of the third group, Orthodox Serbs, also tend to claim Bosnian medieval history as exclusively their own but have not yet shown significant interest in Catherine herself.[40]

Family tree

| Ancestry of Catherine of Bosnia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ^ a b c Regan 2010, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Regan 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b Ljubez 2009, p. 127.

- ^ Pandžić 1979, p. 15.

- ^ Tošić 1997, p. 75.

- ^ a b Mandić 1960, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d Fine 2007, p. 241.

- ^ Pandžić 1979, p. 16.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Pandžić 1979, p. 17.

- ^ Ljubez 2009, p. 141.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 17.

- ^ Ljubez 2009, p. 128.

- ^ Regan 2010, pp. 18–19.

- ^ a b c Mandić 1960, p. 277.

- ^ a b c d Regan 2010, p. 19.

- ^ Pandžić 1979, p. 18.

- ^ Regan 2010, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 22.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 23.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 9.

- ^ a b Regan 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 31.

- ^ Pandžić 1979, p. 19.

- ^ a b Regan 2010, p. 32.

- ^ a b Regan 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Pandžić 1979, pp. 20–21.

- ^ a b c d Regan 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Pandžić 1979, p. 23.

- ^ Pandžić 1979, p. 24.

- ^ Tošić 1997, p. 111.

- ^ Regan 2010, p. 73.

- ^ a b Regan 2010, p. 75.

- ^ Palavestra 1979, p. 94.

- ^ Lovrenović 2014.

Sources

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (2007), The Bosnian Church: Its Place in State and Society from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century, Saqi, ISBN 978-0863565038

- Lovrenović, Ivan (25 October 2014). "Čija je kraljica Katarina" (in Serbo-Croatian). Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 10 December 2015.

- Ljubez, Bruno (2009), Jajce Grad: prilog povijesti posljednje bosanske prijestolnice (in Serbo-Croatian), HKD Napredak

- Mandić, Dominik (1960), Bosna i Hercegovina: Državna i vjerska pripadnost sredovječne Bosne i Hercegovine (in Serbo-Croatian), Croatian Historical Institute

- Palavestra, Vlajko (1979), "Narodna predanja o bježanju kraljice Katarine iz Bosne", Povijesnoteološki simpozij u povodu 500 obljetnice smrti bosanske kraljice Katarine (in Serbo-Croatian), Franjevačka teologija u Sarajevu

- Pandžić, Bazilije (1979), "Katarina Vukčić Kosača (1424–1478)", Povijesnoteološki simpozij u povodu 500 obljetnice smrti bosanske kraljice Katarine (in Serbo-Croatian), Franjevačka teologija u Sarajevu

- Regan, Krešimir (2010), Bosanska kraljica Katarina (in Serbo-Croatian), Breza, ISBN 978-9537036553

- Tošić, Đuro (1997), "Bosanska kraljica Katarina (1425–1478)", Zbornik za istoriju Bosne i Hercegovine 2 (in Serbo-Croatian), Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts