Captaincy General of Santo Domingo

Captaincy General of Santo Domingo Capitania General de Santo Domingo (Spanish) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1492–1865 | |||||||||||

coat of arms of the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo | |||||||||||

| Motto: Plus ultra "Further Beyond" | |||||||||||

| Anthem: Marcha Real "Royal March" (1775–1821) | |||||||||||

Left: Flag of Spain {18th century): first national flag of Spain; Right: Flag of the Province of Santo Domingo; Bottom: Flag Cross of Burgundy

| |||||||||||

Map of the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo , when the entire island belonged to Spain (1492-1605). To the west can be seen the old Spanish villages of Lares de Guahaba, Puerto Real, Villanueva de Jaquimo, Salvatierra de la Sabana, Santa María de la Yaguana and Santa María de la Verapaz. | |||||||||||

| Status | Captaincy General of the Spanish Empire | ||||||||||

| Capital | Santo Domingo | ||||||||||

| Official languages | Spanish | ||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (official) | ||||||||||

| Monarch | |||||||||||

• 1492–1504 | Isabella I of Castile (first) | ||||||||||

• 1861–1865 | Isabella II (last) | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1492–1499 | Christopher Columbus (first) | ||||||||||

• 1864–1865 | José de la Gándara y Navarro (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Council of the Indies Ministry of Overseas (Spain) | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Colonial era | ||||||||||

| 1492 | |||||||||||

• Santo Domingo annexed to France | 1795 | ||||||||||

• Santo Domingo returned to Spain | 1815 | ||||||||||

• Unrecognized independence | 1821 | ||||||||||

• Reincorporated into Spain | 1861 | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1865 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish colonial real | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

| History of the Dominican Republic |

|---|

|

| Pre-Spanish Hispaniola (–1492) |

| Captaincy General of Santo Domingo (1492–1795) |

| French Santo Domingo (1795–1809) |

| España Boba (1809–1821) |

| Republic of Spanish Haiti (1821–1822) |

|

|

| Republic of Haiti (1820–1849) |

|

|

| First Republic (1844–1861) |

|

|

| Spanish occupation (1861–1865) |

| Second Republic (1865–1916) |

| United States occupation (1916–1924) |

| Third Republic (1924–1965) |

| Fourth Republic (1966–) |

| Topics |

|

LGBT history Postal history Jewish history |

|

|

The Captaincy General of Santo Domingo (Spanish: Capitanía General de Santo Domingo pronounced [kapitaˈni.a xeneˈɾal de ˈsanto ðoˈmiŋɡo] ) was the first Capitancy in the New World, established by Spain in 1492 on the island of Hispaniola. The Capitancy, under the jurisdiction of the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo, was granted administrative powers over the Spanish possessions in the Caribbean and most of its mainland coasts, making Santo Domingo the principal political entity of the early colonial period.[1]

Due to its strategic location, the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo served as headquarters for Spanish conquistadors on their way to the mainland and was important in the establishment of other European colonies in the Western Hemisphere. It is the site of the first European city in the Americas, Santo Domingo, and of the oldest castle, fortress, cathedral, and monastery in the region. The colony was a meeting point of European explorers, soldiers, and settlers who brought with them the culture, architecture, laws, and traditions of the Old World.

The colony remained a military stronghold of the Spanish Empire for over a century, successfully defending against British, Dutch, and French expeditions into the region until the early 17th century. After pirates working for the French colonial empire took over part of the west coast, French settlers arrived and decades of armed conflict ensued. Spain finally ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France in the 1697 Peace of Ryswick, thus establishing the basis for the future nations of the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

History

Pre-Columbian era

Prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus and the Spanish in 1492, the native Taíno people populated the island which they called Ayiti ("land of high mountains") or "Quisqueya" (from Quizqueia), meaning "great thing" or "big land" ("mother of all lands"), and which the Spanish later named Hispaniola. At the time, the island's territory consisted of five Taíno chiefdoms: Marién, Maguá, Maguana, Jaragua, and Higüey.[2] These were ruled respectively by caciques (chiefs) Guacanagarix, Guarionex, Caonabo, Bohechío, and Cayacoa.

Arrival of the Spanish

On his first voyage the navigator Christopher Columbus, arrived in 1492 under the Spanish Crown as he landed on a large island in the region of the western Atlantic Ocean that later came to be known as the Caribbean. Columbus promptly claimed the island for the Spanish Crown, naming it La Isla Española ("the Spanish Island"), later Latinized to Hispaniola. He established a settlement in the northern part of the island, which later came under attack by the people of the area. The native Taínos' egalitarian social system clashed with the Europeans' feudalist system, which had more rigid class structures. The Europeans believed the Taínos to be misled, and they began to treat the tribes with violence and hatred.

Conquest and settlements

After the sinking of the Santa María ship Columbus established a military fort to support his claim to the island. The fort was called La Navidad because the shipwrecking and the founding of the fort occurred on Christmas Day. While Columbus was away, the garrison manning the fort was wracked by divisions that evolved into conflict. The more rapacious men began to terrorize the Taíno, the Ciguayos, and the Macorix people. The powerful Cacique Caonabo of the Maguana Chiefdom attacked the Europeans and destroyed La Navidad.

In 1493, Columbus returned to the island on his second voyage and established the first Spanish colony in the New World, the city of Isabella. This time Columbus returned to Hispaniola with seventeen ships. The settlers built houses, storerooms, a Roman Catholic church, and a large house for Columbus. He brought more than a thousand men, including sailors, soldiers, carpenters, stonemasons, and other workers. Priests and nobles came as well. The first Mass was celebrated on 6 January 1494. The town included homes, a plaza, and Columbus' stone residence and arsenal.[3]: 22

In June 1495, a large storm that the Taíno called a hurricane hit the island. The Taíno retreated to the mountains while the Spaniards remained in the colony. Several ships were sunk, including the flagship, the Marie-Galante. Cannon barrels and anchors from that era have been found in the bay. Gelatinous silt from rivers and wave action has raised the level of the bay floor and covers any parts of wrecks that may remain.[citation needed]

In 1496, his brother Bartholomew Columbus established the settlement of Santo Domingo de Guzmán on the southern coast, which became the new capital. An estimated 400,000 Tainos living on the island were soon enslaved to work in gold mines. By 1508, their numbers had decreased to around 60,000 because of forced labor, hunger, disease, and mass killings. By 1535, only a few dozen were still alive.[4]

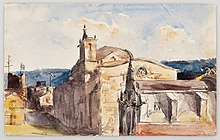

Dating from 1496, when the Spanish settled on the island, and officially from 5 August 1498, Santo Domingo became the first European city in the Americas. Bartholomew Columbus founded the settlement and named it La Nueva Isabela, after an earlier settlement in the north named after the Queen of Spain Isabella I.[5] In 1495 it was renamed "Santo Domingo", in honor of Saint Dominic.

The expectations of obtaining great wealth in the island had been high for those who had arrived, and the violent nature and competitive drive of the colonizers also created conflicts among them. In 1497, a colonial administrator Francisco Roldán rebelled against Columbus and established a rival regime in the island, recruiting half of the Spanish in 1498, and all the towns and fortresses had joined him except La Vega and La Isabella.[6][7][8]

Roldán also promised to exempt some Indians from paying tribute, which they did with gold they collected from the rivers, if they gave him their support, thus getting the help of some natives. Roldán took weapons from La Isabela and retired to Xaragua. When Christopher Columbus returned to America in 1498 on his third voyage, he began a pact with the rebels, which was signed in August 1499, where he agreed to allow the use of the indigenous people as personal service, and gave back pay for the last two years. Even to those who had not worked, he distributed land, authorized the Spaniards to join with the Tainos and to return to Spain whenever they wished. Roldán was also reinstated as Mayor of La Isabela and, in March 1500, Roldán himself helped put down a rebellion led by Pedro Riquelme and Adrián de Mújica against Columbus.

Roldan died in 1502, in a hurricane that occurred coinciding with Columbus's arrival in America on his fourth voyage to the Indies. That hurricane would also kill Francisco de Bobadilla, the investigative judge who ordered Columbus' arrest in August 1500.[9]

Establishment of Santo Domingo

Santo Domingo came to be known as the "Gateway to the New World" and the chief city and capital of all Spanish colonies in the Americas during the colonization era.[10] Spanish Expeditions which led to Ponce de León's colonization of Puerto Rico, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar's colonization of Cuba, Hernán Cortés' conquest of Mexico, and Vasco Núñez de Balboa's discovery of the Pacific Ocean were all launched from Santo Domingo.

A large discovery of gold was also found in the island, in the Cordillera Central mountain region, which led to a mining boom and a gold rush that lasted from 1500 until 1508.[3]: 44, 50, 57–58, 74 Ferdinand II of Aragon "ordered gold from the richest mines reserved for the Crown." The total sum of gold extracted during the first two decades in the Island was estimated at 30,000 kilos, an amount greater than the totality of production in Europe in those years and above the total gold collected by the Portuguese in Africa.

The colony's Spanish leadership changed several times, when Columbus departed on another exploration, Francisco de Bobadilla became governor. Settlers' allegations of mismanagement by Columbus helped create a tumultuous political situation. In 1502, Nicolás de Ovando replaced de Bobadilla as governor, it was he who dealt most brutally with the Taíno people. In June 1502,[11] Santo Domingo was destroyed by a major hurricane, and the new Governor Nicolás de Ovando had it rebuilt on a different site on the other side of the Ozama River.[12][3]: 55, 73

In 1503 the Hospital San Nicolás de Bari, first hospital in the Americas, begins construction at the behest of governor (and namesake of the hospital) Nicolás de Ovando. This grand project was in keeping with the desire to emulate European princely courts, and looked to Renaissance Italy for inspiration.[13] At the time of its completion, the wards could accommodate up to 70 patients, comparable to the most advanced churches of Rome.[14]

In 1509, the Atarazanas Reales (Royal Shipyards), a waterside building that housed the shipyards, warehouses, customs house and tax offices in the port of Santo Domingo, began construction.[15] In addition to serving as warehouses, the complex also housed the Santo Domingo office of the Casa de Contratación, headquartered in Seville. Thus, the Atarazanas also served as the first customs and tax house of the New World. Management was contracted by the Crown to the powerful Welser banking family, which had a slave-trading empire.

Enslavement of Africans

The Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand I and Isabella granted permission to the colonists of the Caribbean to import African slaves, and in 1510 the first sizable shipment consisting of 250 Black Ladinos arrived in Hispaniola from Spain. Eight years later African-born slaves arrived in the West Indies. Sugar cane was introduced to Hispaniola from the Canary Islands, and the first sugar mill in the New World was established in 1516.[16] The need for a labor force to meet the growing demands of sugar cane cultivation led to an exponential increase in the importation of slaves over the following two decades. The sugar mill owners soon formed a new colonial elite, and initially convinced the Spanish king to allow them to elect the members of the Real Audiencia from their ranks. Diego Colón arrived in 1509, assuming the powers of Viceroy and admiral. In 1512, Ferdinand established a Real Audiencia with Juan Ortiz de Matienzo, Marcelo de Villalobos, and Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón appointed as judges of appeal. In 1514, Pedro Ibanez de Ibarra arrived with the Laws of Burgos. Rodrigo de Alburquerque was named repartidor de indios and soon named visitadores to enforce the laws.[3]: 143–144, 147

The first major slave revolt in the Americas occurred in Santo Domingo on 26 December 1522, when enslaved Muslims of the Wolof nation led an uprising in the sugar plantation of admiral Don Diego Colón, son of Christopher Columbus. Many of these insurgents managed to escape to the mountains where they formed independent maroon communities in the south of the island, but the Admiral also had a lot of captured rebels hanged.[17]

Another rebel also fought back, the native Taino Enriquillo led a group who fled to the mountains and attacked the Spanish repeatedly for fourteen years. The Spanish ultimately offered him a peace treaty and gave Enriquillo and his followers their own city in 1534. By 1545, there were an estimated 7,000 maroons beyond Spanish control on Hispaniola. The Bahoruco Mountains in the south-west were their main area of concentration, although Africans had escaped to other areas of the island as well.

By the 1540s, the Caribbean Sea had become overrun with European pirates from England, France, and the Netherlands. In 1541, Spain authorized the construction of Santo Domingo's fortified wall, and decided to restrict sea travel to enormous, well-armed convoys. In another move, which would destroy Hispaniola's sugar industry, Havana, more strategically located in relation to the Gulf Stream, was selected as the designated stopping point for the merchant flotas, which had a royal monopoly on commerce with the Americas. With the conquest of the Spanish Main, Hispaniola slowly declined. Many Spanish colonists left for the silver mines of the American mainland, while new immigrants from Spain bypassed the island. Agriculture dwindled, new imports of slaves ceased, and white colonists, free blacks, and slaves alike lived in poverty, weakening the racial hierarchy and aiding intermixing, resulting in a population of predominantly mixed Spaniard, Taíno, and African descent. Except for the city of Santo Domingo, which managed to maintain some legal exports, Dominican ports were forced to rely on contraband trade, which, along with livestock, became the sole source of livelihood for the island dwellers.

British and French incursions

In 1586, Francis Drake captured the city and held it for ransom.[18] Drake's invasion signaled the decline of Spanish dominion over the Caribbean region, which was accentuated in the early 17th century by policies that resulted in the depopulation of most of the island outside of the capital. An expedition sent by Oliver Cromwell in 1655 attacked the city of Santo Domingo, but was defeated. The English troops withdrew and took the less guarded colony of Jamaica, instead.[19] In 1697, the Treaty of Ryswick included the acknowledgement by Spain of France's dominion over the Western third of the island, now Haiti.

In 1605, Spain, unhappy that Santo Domingo was facilitating trade between its other colonies and other European powers, attacked vast parts of the colony's northern and western regions, forcibly resettling their inhabitants closer to the city of Santo Domingo.[20] This action, known as the devastaciones de Osorio, proved disastrous; more than half of the resettled colonists died of starvation or disease.[21] The city of Santo Domingo was subjected to a smallpox epidemic, cacao blight, and hurricane in 1666; another storm two years later; a second epidemic in 1669; a third hurricane in September 1672; plus an earthquake in May 1673 that killed two dozen residents.[22] San José de Ocoa, the best-known maroon settlement in Santo Domingo, was subjugated by the Spanish in 1666.

In the 17th century, the French began occupying the unpopulated western third of Hispaniola. In 1625, French and English pirates arrived on the western side of the island. The pirates were attacked in 1629 by Spanish forces commanded by Don Fadrique de Toledo, who fortified the island, and expelled the French and English. In 1654, the Spanish re-captured the west side the island.[23]

In 1655 the west of Hispaniola was reoccupied by the English and French. In 1660 the English appointed a Frenchman as Governor who proclaimed the King of France, set up French colours, and defeated several English attempts to reclaim the island.[24] In 1665, French colonization of the island was officially recognized by King Louis XIV. The French colony was given the name Saint-Domingue. By 1670 a Welsh privateer named Henry Morgan invited the pirates on the island of Tortuga to set sail under him. They were hired by the French as a striking force that allowed France to have a much stronger hold on the Caribbean region. Consequently, the pirates never really controlled the island and kept Tortuga as a neutral hideout. The capital of the French Colony of Saint-Domingue was moved from Tortuga to Port-de-Paix on the mainland of Hispaniola in 1676.

In 1680, new Acts of Parliament forbade sailing under foreign flags (in opposition to former practice). This was a major legal blow to the Caribbean pirates. Settlements were made in the Treaty of Ratisbon of 1684, signed by the European powers, that put an end to piracy. Most of the pirates after this time were hired out into the Royal services to suppress their former buccaneer allies. In the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick, Spain formally ceded the western third of the island to France.[25][26] It was an important port in the Americas for goods and products flowing to and from France and Europe. Intermittent clashes between French and Spanish colonists followed, even after the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick recognized the de facto occupations of France and Spain around the globe. Periodic confrontations also continued despite a 1731 agreement that partially defined a border between the two colonies along the Massacre and Pedernales rivers. In 1777, the Treaty of Aranjuez established a definitive border between what Spain called Santo Domingo and what the French named Saint-Domingue, thus ending 150 years of local conflicts and imperial ambitions to extend control over the island.[27]

Economic revival

The House of Bourbon replaced the House of Habsburg in Spain in 1700 and introduced economic reforms that gradually began to revive trade in Santo Domingo. The crown progressively relaxed the rigid controls and restrictions on commerce between Spain and the colonies and among the colonies. The last flotas sailed in 1737; the monopoly port system was abolished shortly thereafter. Many Spaniards and Hispaniola-born Creoles also then became pirates and privateers. By the middle of the century, the population was bolstered by emigration from the Canary Islands, resettling the northern part of the colony and planting tobacco in the Cibao Valley, and importation of slaves was renewed.

Age of Piracy

Santo Domingo's exports soared and the island's agricultural productivity rose, which was assisted by the involvement of Spain in the Seven Years' War, allowing privateers operating out of Santo Domingo to once again patrol surrounding waters for enemy merchantmen.[28] Dominican pirates captured British, Dutch, French and Danish ships throughout the eighteenth century.[29] Dominicans constituted one of the many diverse units which fought under Bernardo de Gálvez during the conquest of British West Florida (1779–1781).[30][31]

Dominican privateers had already been active in the Guerra del Asiento decades prior, and they sharply reduced the amount of enemy trade operating in West Indian waters.[28] The prizes they took were carried back to Santo Domingo, where their cargoes were sold to the colony's inhabitants or to foreign merchants doing business there. During this period, Spanish privateers from Santo Domingo sailed into enemy ports looking for ships to plunder, thus disrupting commerce between Spain's enemies in the Atlantic. As a result of these developments, Spanish privateers frequently sailed back into Santo Domingo with their holds filled with captured plunder which were sold in Hispaniola's ports, with profits accruing to individual sea raiders. The revenue acquired in these acts of piracy was invested in the economic expansion of the colony and led to repopulation from Europe.[32] The enslaved population of the colony also rose dramatically, as numerous captive Africans were taken from enemy slave ships in West Indian waters.[28] The author of Idea del valor de la Isla Española emphasized the activities of Dominican privateer Lorenzo Daniel (also known as Lorencín Daniel), and noted that in his career as a privateer, Daniel captured more than 60 enemy ships, including "those used for trade as well as war”.[a]

The population of Santo Domingo grew to approximately 125,000 in the year 1791. Of this number, 40,000 were white landowners, about 70,000 were mulatto freedmen, and some 15,000 were black slaves.[34] This contrasted sharply with neighboring Saint-Domingue (Haiti), which had an enslaved population of over 500,000, representing 90% of the French colony's population, and overall seven times as numerous as the Spanish colony of Santo Domingo.[35] The French had become the wealthiest colonists in the Western Hemisphere due to the exploitation of their massive slave population. As restrictions on colonial trade were relaxed, the colonial French elites of St. Domingue offered the principal market for Santo Domingo's exports of beef, hides, mahogany and tobacco. The 'Spanish' settlers, whose blood by now was mixed with that of Taínos, Africans, and Canary Guanches, proclaimed: 'It does not matter if the French are richer than us, we are still the true inheritors of this island. In our veins runs the blood of the heroic conquistadores who won this island of ours with sword and blood.'.[36][37]

Later years

With the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution, the rich urban families linked to the colonial bureaucracy left the island, while most of the rural cattle ranchers remained, even though they lost their principal market. Nevertheless, the Spanish crown saw in the unrest an opportunity to seize all, or part, of the western region of the island in an alliance of convenience with the rebellious slaves. The Spanish governor of Santo Domingo purchased the allegiance of mulatto and black rebel leaders and their personal armies.[38] In July 1793, Spanish forces, including former slaves, crossed the border and pushed back the disheveled French forces before them.[38]

Although the Spanish and Dominican soldiers had been successful in the island during their battles against the French,[38] such had not been the case in the European front, as Spain and Portugal lost the War of the Pyrenees, and on July 22, 1795, the French Republic and Spanish crown signed the Treaty of Basel. Frenchmen were to return to their side of the Pyrenees in Europe and Spanish Santo Domingo was to be ceded to France. This period called the Era de Francia, lasted until 1809 until being recaptured by the Dominican general Juan Sánchez Ramírez in the reconquest of Santo Domingo.

Cities and towns

Society

Education

The St. Thomas Aquinas University, today the Autonomous University of Santo Domingo, is the first institution of higher education in the Americas. It was founded by papal bull in 1538 in Santo Domingo. The headquarters of the university was the Church and Convent of los Dominicos. Founded during the reign of Charles I of Spain, it was originally a seminary operated by Catholic monks of the Dominican Order. Later, the institution received a university charter by Pope Paul III's papal bull In Apostulatus Culmine, dated October 28, 1538.

In its structure and purpose the new university was modeled after the University of Alcalá in the city of Henares, Spain. In this capacity it became a standard-bearer for the medieval ideology of the Spanish Conquest, and gained its royal charter in 1558. In this royal decree, the university was given the name University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (Universidad Santo Tomás de Aquino).

The university was closed in 1801 under the French, but reopened in 1815 as a secular institution.[39]

Religion

The Archdiocese of Santo Domingo is considered the first episcopal seat in America. Of all the dioceses in the north and south of the American continent, only the archbishop of Santo Domingo corresponds to the title of first of the Indies. It is the oldest of the surviving dioceses in the Americas, the Diocese of Santo Domingo was created on August 8, 1511 by Pope Julius II's bull Romanus Pontifex of August 8, 1511. In those days, the diocese of Concepción (today in La Vega, Dominican Republic). In 1527 the diocese of Concepción de la Vega was abolished, leaving the entire island of Hispaniola under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Santo Domingo.

It was elevated to Metropolitan Archdiocese on February 12, 1546, through the bull Super universas orbis ecclesiae of Pope Paul III, being its first archbishop Alonso de Fuenmayor. The Diocese of Puerto Rico, the Diocese of Venezuela (with headquarters in Coro, founded in 1531; today the Archdiocese of Caracas), the Diocese of Cuba (with headquarters in Santiago de Cuba, initially founded in Baracoa in 1518; today Archdiocese of Santiago de Cuba), the Diocese of Honduras (based in Comayagua, initially founded in Trujillo in 1531; today Archdiocese of Tegucigalpa) and the territorial abbey of Jamaica (suppressed in 1655).

Demographics and caste system

The presence of precious metals such as gold boosted migration of thousands of Spaniards to Hispaniola seeking easy wealth. In the year 1510, there were 10,000 Spaniards in the colony of Santo Domingo, and it rose to over 20,000 in 1520. However after the depleting of the gold mines, the island began to depopulate.[40] This was followed by a limited Spanish migration toward Hispaniola, composed overwhelmingly by males. In order to counteract the depopulation and impoverishment of the colony, the Spanish Monarchy allowed the importation of African slaves to hew sugar cane.

Families stopped migrating to the colony, so the lack of Spanish females led to miscegenation, that drove the creation of a caste system, in which Spaniards were at the top, mixed-race people at middle, and Amerindians and black people at the bottom. In order to maintain their status and remain racially pure the caste system was enforced, because only pure whites were able to inherit majorats. As a result, Santo Domingo, like the rest of Hispanic America, became a pigmentocracy. The local-born whites were known as blancos de la tierra ("whites from the land"), in contrast to the blancos de Castilla, "whites from Castile".[41]

Limpieza de sangre (Spanish: [limˈpjeθa ðe ˈsaŋɡɾe], meaning literally "cleanliness of blood") was very important in Mediæval Spain,[42] and this system was replicated on the New World. The highest social class was the Visigothic nobility,[43] commonly known as people of "sangre azul" (Spanish for: "blue blood"), because their skin was so pale that their veins looked blue through it, in comparison with that of a commoner who had olive skin. Those who proved that they were descendants of Visigoths were allowed to use the style of Don and were considered hidalgos. Hidalgos nobles were the most benefited of those Spanish who emigrated to America because they received royal properties (such as cattle, lands, and slaves) and tax exemptions. These people achieved a privileged position, and most of them avoided mixing with natives or Africans.

The Spanish of the highest rank who migrated to America in the sixteenth century was the noblewoman Doña María de Toledo, granddaughter of the 1st Duke of Alba, niece of the 2nd Duke of Alba, and grandniece of King Ferdinand of Aragon; she was married to Diego Columbus, Admiral and Viceroy of the Indies.[citation needed]

Government and Laws

The Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo was the first court of the Spanish crown in America. It was created by Ferdinand V of Castile in his decree of 1511, and was implemented by Charles V in his decree of September 14, 1526. This audiencia would become part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain upon the creation of the latter two decades later.

The audiencia president was at the same time governor and captain general of the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo, which granted him broad administrative powers and autonomy over the Spanish possessions of the Caribbean and most of its mainland coasts. This combined with the judicial oversight that the audiencia judges had over the region meant that the Santo Domingo Audiencia was the principal political entity of this region during the colonial period.

|

Native rights

In 1501 Queen Isabella declared Native Americans as subjects to the crown, this implied that enslaving them was illegal except on very specific conditions. This would lead to the necessity of importing African slaves to the island in the years to come. Native chiefs were responsible for keeping track of the laborers in their community. The encomienda system did not grant people land, but it indirectly aided in the conquistadors and settlers' acquisition of land with the intent of establishing new towns and populations. As initially defined, the encomendero and his heirs expected to hold these grants in perpetuity.

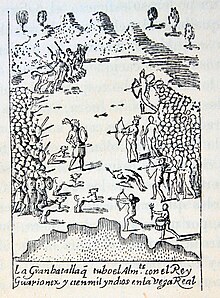

The encomiendas became very corrupt and harsh. In the neighborhood of La Concepción, north of Santo Domingo, the adelantado of Santiago heard rumors of a 15,000-man army of Tainos planning to stage a rebellion.[44] Upon hearing this, the adelantado captured the caciques involved and had most of them hanged.

Later, a chieftain named Guarionex laid havoc to the countryside before an army of about 3,090 routed the Ciguana people under his leadership.[45] Although expecting Spanish protection from warring tribes, the islanders sought to join the Spanish forces. They helped the Spaniards deal with their ignorance of the surrounding environment.[46] The change of requiring the encomendado to be returned to the crown after two generations was frequently overlooked, as the colonists did not want to give up the labor or power.

Gallery

- Contemporary map showing the border situation on Hispaniola following the Treaty of Aranjuez

See also

- List of colonial governors of Santo Domingo

- Timeline of Santo Domingo

- History of the Dominican Republic

- Spanish colonization of the Americas

- Annexation of the Dominican Republic to Spain

- French Colony of Saint-Domingue

Notes

References

- ^ Spain (1680). Recopilación de las Leyes de Indias. Titulo Quince. De las Audiencias y Chancillerias Reales de las Indias. Madrid. Spanish-language facsimile of the original.

- ^ Perez, Cosme E. (20 December 2011). Quisqueya: un país en el mundo: La Revelación Maya Del 2012. Palibrio. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-4633-1368-5. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d Floyd, Troy (1973). The Columbus Dynasty in the Caribbean, 1492–1526. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- ^ Hartlyn, Jonathan (1998). The Struggle for Democratic Politics in the Dominican Republic. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-8078-4707-0.

- ^ Greenberger, Robert (1 January 2003). Juan Ponce de León: The Exploration of Florida and the Search for the Fountain of Youth. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8239-3627-4. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Bakewell, Peter John (2004), A history of Latin America: c. 1450 to the present, Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, p. 83, ISBN 0-631-23160-9.

- ^ Peter Bakewell, "A History of Latin America to 1825: 3rd Edition", pg 114 Wiley Blackwell, 2010. Retrieved 4/11/2016.

- ^ Columbus, Ferdinand (1959). The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his son Ferdinand. New Brunswick: Rutgers, The State University. pp. 191–214.

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1942), Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus, Boston: Little, Brown and Co., p. 590.

- ^ Bolton, Herbert E.; Marshall, Thomas Maitland (30 April 2005). The Colonization of North America 1492 to 1783. Kessinger Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7661-9438-0. Retrieved 4 June 2012.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Clayton, Lawrence A. (25 January 2011). Bartolom de Las Casas and the Conquest of the Americas. John Wiley & Sons. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4051-9427-3. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ Meining 1986:9

- ^ Bailey, Galvin Alexander (2005). Art of Colonial Latin America. New York: Phaidon Press. p. 133. ISBN 0714841579.

- ^ Palm, Erwin Walter (1955). Los Monumentos Arquitectónicos de La Española, Con una introducción a América. 2 vols. Ciudad Trujillo: Universidad de Santo Domingo.

- ^ Banco Popular. Santo Domingo Colonial: Sus Principales Monumentos. Santo Domingo: Banco Popular, 1998

- ^ Sharpe, Peter (26 October 1998). "Sugar Cane: Past and Present". Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ Jose Franco, Maroons and Slave Rebellions in the Spanish Territories, in "Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas", ed. by Richard Price (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), p. 35.

- ^ "Dominican Republic – THE FIRST COLONY". Library of Congress. Retrieved 18 March 2009.

- ^ Marley, David (1998). Wars of the Americas. ABC-CLIO. pp. 148–149. ISBN 9780874368376.

- ^ Knight, Franklin W. (1990). The Caribbean: The Genesis of a Fragmented Nationalism (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 54. ISBN 0-19-505440-7.

- ^ Harvey, Sean (2006). The Rough Guide to the Dominican Republic (3rd ed.). New York: Rough Guides. pp. 352. ISBN 1-84353-497-5.

- ^ Marley, David (2005). Historic Cities of the Americas: An Illustrated Encyclopedia, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 94.

- ^ The Buccaneers In The West Indies In The XVII Century – Chapter IV

- ^ The Buccaneers In The West Indies In The XVII Century – Chapter IV

- ^ "Hispaniola Article". Britannica.com. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ "Dominican Republic 2014". Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. p. 422.

- ^ a b c Hazard, Samuel (1873). Santo Domingo, Past And Present; With A Glance At Haytl. p. 100.

- ^ "Corsairs of Santo Domingo a socio-economic study, 1718–1779" (PDF).

- ^ Figueredo, D. H. (2007). Latino Chronology: Chronologies of the American Mosaic. ISBN 9780313341540.

- ^ Chavez, Thomas E. (2002). Spain and the Independence of the United States: An Intrinsic Gift. ISBN 9780826327949.

- ^ Ricourt, Milagros (2016). The Dominican Racial Imaginary: Surveying the Landscape of Race and Nation in Hispaniola. Rutgers University Press. p. 57.

- ^ Bosch, Juan (2016). Social Composition of the Dominican Republic. Routledge. p. 101.

- ^ Valverde, Antonio Sánchez (1862). idea del valor de la isla española.

- ^ "Dominican Republic – THE FIRST COLONY". Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- ^ Peasants and Religion: A Socioeconomic Study of Dios Olivorio and the Palma Sola Religion in the Dominican Republic. p. 565.

- ^ "Dominican Republic—The First Colony". U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved 15 July 2008.

- ^ a b c Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars: Volume 1. Potomac Books.

- ^ "Las Universidades" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 2 May 2015.

- ^ Bosch, Juan (1995). Composición Social Dominicana (PDF) (in Spanish) (18 ed.). Santo Domingo: Alfa y Omega. p. 45. ISBN 9789945406108. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

"Aunque, siguiendo a Herrera, Sánchez Valverde diga que después de lo que escribió Oviedo aumentó el número de ingenios, parece que el punto más alto de la expansión de la industria azucarera se consiguió precisamente cuando Oviedo escribía sobre ella en 1547. Ya entonces había comenzado el abandono de la isla por parte de sus pobladores, que se iban hacia México y Perú en busca de una riqueza que no hallaban en la Española".

- ^ Moreau de Saint-Méry, Médéric Louis Élie. Description topographique et politique de la partie espagnole de l'isle Saint-Domingue. Philadelphia. pp. 55–59.

- ^ "The Visigoths in Spain" (aspx). Spain Then and Now. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ^ Kurlansky, Mark (30 September 2011). The Basque History Of The World. Random House. ISBN 9781448113224.

- ^ Pietro Martire D'Anghiera (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 121. ISBN 9781113147608. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ Pietro Martire D'Anghiera (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 143. ISBN 9781113147608. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ^ Pietro Martire D'Anghiera (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. p. 132. ISBN 9781113147608. Archived from the original on 31 July 2020. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

Further reading

- "Santo Domingo". Encyclopædia Metropolitana. Vol. 18. London: B. Fellowes et al. 1845. hdl:2027/mdp.39015082485213.