Caerphilly Castle

| Caerphilly Castle | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Caerphilly County Borough | |

| Caerphilly, Wales, United Kingdom | |

Caerphilly Castle and moat | |

| Type | Medieval concentric castle |

| Area | Around 30 acres (12 ha) |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Cadw |

| Condition | Ruined, with partial restoration |

| Site history | |

| Built |

|

| Built by |

|

| In use | Open to public |

| Materials | Pennant Sandstone |

| Events | Welsh Wars Invasion of England English Civil War |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Official name | Caerphilly Castle[1] |

| Designated | 28/01/1963[1] |

| Reference no. | 13539[1] |

| Official name | Caerphilly Castle[2] |

| Reference no. | GM002[2] |

Caerphilly Castle (Welsh: Castell Caerffili) is a medieval fortification in Caerphilly in South Wales. The castle was constructed by Gilbert de Clare in the 13th century as part of his campaign to maintain control of Glamorgan, and saw extensive fighting between Gilbert, his descendants, and the native Welsh rulers. Surrounded by extensive artificial lakes – considered by historian Allen Brown to be "the most elaborate water defences in all Britain" – it occupies around 30 acres (12 ha) and is the largest castle in Wales and the second-largest castle in the United Kingdom after Windsor Castle.[3] It is famous for having introduced concentric castle defences to Britain and for its large gatehouses. Gilbert began work on the castle in 1268 following his occupation of the north of Glamorgan, with the majority of the construction occurring over the next three years at a considerable cost. The project was opposed by Gilbert's Welsh rival Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, leading to the site being burnt in 1270 and taken over by royal officials in 1271. Despite these interruptions, Gilbert successfully completed the castle and took control of the region. The core of Caerphilly Castle, including the castle's luxurious accommodation, was built on what became a central island, surrounding by several artificial lakes, a design Gilbert probably derived from that at Kenilworth. The dams for these lakes were further fortified, and an island to the west provided additional protection. The concentric rings of walls inspired Edward I's castles in North Wales, and proved what historian Norman Pounds has termed "a turning point in the history of the castle in Britain".[4]

The castle was attacked during the Madog ap Llywelyn revolt of 1294, the Llywelyn Bren uprising in 1316 and during the overthrow of Edward II in 1326–27. In the late 15th century, however, it fell into decline and by the 16th century the lakes had drained away and the walls were robbed of their stone. The Marquesses of Bute acquired the property in 1776 and under the third and fourth Marquesses extensive restoration took place. In 1950 the castle and grounds were given to the state and the water defences were re-flooded. In the 21st century, the Welsh heritage agency Cadw manages the site as a tourist attraction.

History

13th century

Caerphilly Castle was built in the second half of the 13th century, as part of the Anglo-Norman expansion into South Wales. The Normans began to make incursions into Wales from the late 1060s onwards, pushing westwards from their bases in recently occupied England.[5] Their advance was marked by the construction of castles and the creation of regional lordships.[6] The task of subduing the region of Glamorgan was given to the earls of Gloucester in 1093; efforts continued throughout the 12th and early 13th centuries, accompanied by extensive fighting between the Anglo-Norman lords and local Welsh rulers.[7] The powerful de Clare family acquired the earldom in 1217 and continued to attempt to conquer the whole of the Glamorgan region.[8]

In 1263, Gilbert de Clare, also known as "Red Gilbert" because of the colour of his hair, inherited the family lands.[9] Opposing him in Glamorgan was the native Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.[8] Llywelyn had taken advantage of the chaos of the civil war in England between Henry III and rebel barons during the 1260s to expand his power across the region.[10] In 1265 Llywelyn allied himself with the baronial faction in England in exchange for being granted authority over the local Welsh magnates across all the territories in the region, including Glamorgan.[11] De Clare believed his lands and power were under threat and allied himself with Henry III against the rebel barons and Llywelyn.[12]

The baronial revolt was crushed between 1266 and 1267, leaving de Clare free to advance north into Glamorgan from his main base in Cardiff.[13] De Clare started to construct a castle at Caerphilly to control his new gains in 1268. The castle lay in a basin of the Rhymney Valley, alongside the Rhymney River and at the heart of network of paths and roads, adjacent to a former Roman fort.[14] Work began at a huge pace, with ditches cut to form the basic shape of the castle, temporary wooden palisades erected and extensive water defences created by damming a local stream.[15] The walls and internal buildings were built at speed, forming the main part of the castle.[15] The architect of the castle and the precise cost of the construction are unknown, but modern estimates suggest that it could have cost as much as castles such as Conwy or Caernarfon, perhaps as much as £19,000, a huge sum for the period.[16]

Llywelyn responded by intervening with his own forces but outright conflict was prevented by the diplomatic efforts of Henry III.[17] De Clare continued building work and in 1270 Llywelyn responded by attacking and burning the site, probably destroying the temporary defences and stores.[18] De Clare began work again the following year, raising tensions and prompting Henry to send two bishops, Roger de Meyland and Godfrey Giffard, to take control of the site and arbitrate a solution to the dispute.[19]

The bishops took possession of the castle later in 1271 and promised Llywelyn that building work would temporarily cease and that negotiations would begin the following summer.[19] In February of the next year, however, de Clare's men seized back the castle, threw out the bishops' soldiers, and de Clare – protesting his innocence in these events – began work once again.[19] Neither Henry nor Llywelyn could readily intervene and de Clare was able to lay claim to the whole of Glamorgan.[15] Work on the castle continued, with additional water defences, towers and gatehouses added.[20]

Llywelyn's power declined over the next two decades. In 1277 Henry's son, Edward I, invaded Wales following a dispute with the prince, breaking his power in South Wales, and in 1282 Edward's second campaign resulted in Llywelyn's death and the collapse of independent Welsh rule.[15] Further defences were added to the walls until work stopped around 1290.[21] Local disputes remained. De Clare argued with Humphrey de Bohun, the earl of Hereford, in 1290 and the following year the case was brought before the king, resulting in the temporary royal seizure of Caerphilly.[21]

In 1294 Madog ap Llywelyn rebelled against English rule, the first major insurrection since the 1282 campaign.[22] The Welsh appear to have risen up over the introduction of taxation and Madog had considerable popular support.[22] In Glamorgan, Morgan ap Maredudd led the local uprising; Morgan had been dispossessed by de Clare in 1270 and saw this as a chance to regain his lands.[23] Morgan attacked Caerphilly, burning half of the town, but failed to take the castle.[23] In the spring of 1295 Edward pressed home a counter-attack in North Wales, putting down the uprising and arresting Madog.[22] De Clare attacked Morgan's forces and retook the region between April and May, resulting in Morgan's surrender.[23] De Clare died at the end of 1295, leaving Caerphilly Castle in a good condition, linked to the small town of Caerphilly which had emerged to the south of it and a large deer park in the nearby Aber Valley.[24]

14th – 17th centuries

Gilbert's son, also called Gilbert de Clare, inherited the castle, but he died fighting at the battle of Bannockburn in 1314 while still quite young.[25] The family's lands were initially placed under the control of the Crown, but before any decision could be taken on the inheritance, a revolt broke out in Glamorgan.[19] Anger over the actions of the royal administrators caused Llywelyn Bren to rise up in January 1316, attacking Caerphilly Castle with a large force of men.[25] The castle withstood the attack, but the town was destroyed and the rebellion spread.[25] A royal army was despatched to deal with the situation, defeating Bren in a battle at Caerphilly Mountain and breaking the Welsh siege of the castle.[25]

In 1317 Edward II settled the inheritance of Glamorgan and Caerphilly Castle on Eleanor de Clare, who had married the royal favourite, Hugh le Despenser.[26] Hugh used his relationship with the king to expand his power across the region, taking over lands throughout South Wales.[27] Hugh employed Master Thomas de la Bataile and William Hurley to expand the Great Hall at the castle in 1325–1326, including richly carved windows and doors.[28] In 1326, however, Edward's wife, Isabella of France, overthrew his government, forcing the king and Hugh to flee west.[27][29] The pair stayed in Caerphilly Castle at the end of October and early November, before leaving to escape Isabella's approaching forces, abandoning the extensive stores and £14,000 held at the castle.[30] William la Zouche besieged the castle with a force of 425 soldiers, cornering the constable, Sir John de Felton, Hugh's son – also called Hugh – and the garrison of 130 men inside.[31] Caerphilly held out until March 1327, when the garrison surrendered on the condition that the younger Hugh was pardoned, his father having been already executed.[31]

Tensions between the Welsh and the English persisted and spilled over in 1400 with the outbreak of the Glyndŵr Rising.[32] It is uncertain what part the castle played in the conflict, but it seems to have survived intact.[33] It was captured by the forces of Glyndwr during the rebellions.[34][35] In 1416, the castle passed through Isabel le Despenser in marriage to her first husband Richard de Beauchamp, the earl of Worcester, and then to her second husband, Richard Beauchamp, the earl of Warwick.[36] Isabel and her second husband invested heavily in the castle, conducting repairs and making it suitable for use as their main residence in the region.[37] The castle passed to Richard Neville in 1449 and to Jasper Tudor, the earl of Pembroke, in 1486.[38]

After 1486, the castle went into decline, eclipsed by the more fashionable residence of Cardiff Castle; once the sluice-gates fell into disrepair, the water defences probably drained away.[39] Antiquarian John Leland visited Caerphilly Castle around 1539, and described it as having "waulles of a wonderful thiknes", but beyond a tower used to hold prisoners it was in ruins and surrounded by marshland.[40] Henry Herbert, the earl of Pembroke used the castle for his manorial court.[33] In 1583 the castle was leased to Thomas Lewis, who stripped it of much of its stone to extend his house, causing extensive damage.[40]

In 1642 the English Civil War broke out between the Royalist supporters of Charles I and those of Parliament. South Wales was predominantly Royalist in sympathy, and during the conflict, a sconce, or small fort, was built overlooking Caerphilly Castle to the north-west, on the site of the old Roman fort.[41] It is uncertain if this was built by Royalist forces or by the Parliamentary army that occupied the area during the final months of the war in March 1646, but the fort's guns would have dominated the interior of the castle.[42] It is also uncertain whether or not Caerphilly Castle was deliberately slighted by Parliament to prevent its future use as a fortification. Although several towers had collapsed by the 18th century, possibly as a result of such an operation, it is probable that this deterioration was actually the result of subsidence damage caused when the water defences retreated, as there is no evidence of deliberate destruction having been ordered.[43]

18th – 21st centuries

The Marquesses of Bute acquired the castle in 1776.[44] John Stuart, the first marquess, took steps to protect the ruins.[31] His great-grandson John Crichton-Stuart, the third marquess, was immensely rich as the result of the family's holdings in the South Wales coalfields and was passionately interested in the medieval period.[45] He had the site fully surveyed by the architect William Frame, and reroofed the great hall in the 1870s.[31] The marquess began a process of buying back leasehold properties around the castle with the intent of clearing back the town houses that had been built up to the edge of the site.[46]

The fourth marquess, John Crichton-Stuart, was an enthusiastic restorer and builder and commissioned a major restoration project between 1928 and 1939.[47] The stonework was carefully repaired, with moulds made to recreate missing pieces.[44] The Inner East Gatehouse was rebuilt, along with several of the other towers.[48] The marquess carried out landscaping work, with the intent of eventually re-flooding the lakes, and thanks to several decades of purchases was finally able to demolish the local houses encroaching on the view of the castle.[49]

By 1947, when John Crichton-Stuart, the fifth marquess, inherited the castle, the Bute family had divested itself of most of its land in South Wales.[50] John sold off the family's remaining property interests and in 1950 he gave Caerphilly Castle to the state.[51] The lakes were re-flooded and the final stages of the restoration work were completed in the 1950s and 1960s.[48] In the 21st century the castle is managed by the Welsh heritage agency Cadw as a tourist attraction.[48] In 2006, the castle saw 90,914 visitors.[52] It is protected as a scheduled monument and as a grade I listed building. The Great Hall is available for wedding ceremonies.[53]

Architecture

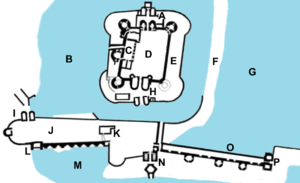

Caerphilly Castle comprises a set of eastern defences, protected by the Outer East Moat and the North Lake, and fortifications on the Central Island and the Western Island, both protected by the South Lake.[54] The site is around 30 acres (120,000 m2) in size, making it the second largest in Britain.[55] It is constructed on a natural gravel bank in the local river basin, and the castle walls are built from Pennant sandstone.[56] The castle's architecture is famous and historically significant.[57] The castle introduced concentric castle defences to Britain, changing the future course of the country's military architecture, and also incorporated a huge gatehouse.[58] The castle also featured a sophisticated network of moats and dams, considered by historian Allen Brown to be "the most elaborate water defences in all Britain".[3]

The eastern defences were reached via the Outer Main Gatehouse, which featured circular towers resting on spurred, pyramidic bases, a design particular to South Wales castles.[59] Originally the gatehouse would have been reached over a sequence of two drawbridges, linked by an intervening tower, since destroyed.[60] To the north side of the gatehouse was the North Dam, protected by three substantial towers, and which may have supported the castle's stables.[61] Despite subsidence damage, the dam still holds back the North Lake.[60] The South Dam was a massive structure, 152 metres (499 ft) long, ending in a huge buttressed wall.[62] The remains of the castle mill – originally powered by water from the dam – survive. Four replica siege engines have been placed on display.[63] The dam ended in Felton's Tower, a square fortification designed to protect the sluicegates regulating the water levels of the dam, and the South Gatehouse – also called Giffard's Tower – originally accessed via a drawbridge, which led into the town.[64]

Caerphilly's water defences were almost certainly inspired by those at Kenilworth, where a similar set of artificial lakes and dams was created.[65] Gilbert de Clare had fought at the siege of Kenilworth in 1266 and would have seen these at first hand.[65] Caerphilly's water defences provided particular protection against mining, which could otherwise undermine castle walls during the period, and are considered the most advanced of their kind in Britain.[66]

The central island held Caerphilly's inner defences, a roughly square design with a walled inner and middle ward, the inner ward protected by four turrets on each of the corners.[67] The walls of the inner ward overlooked those of the middle ward, producing a concentric defence of two enclosed rings of walls; in the medieval period, the walls of the middle ward would have been much higher than today, forming a more substantial defence.[68] Caerphilly was the first concentric castle in Britain, pre-dating Edward I's famous programme of concentric castles by a few years.[69] The design influenced the design of Edward's later castles in North Wales, and historian Norman Pounds considers it "a turning point in the history of the castle in Britain".[70] Probable subsidence has caused the south-east tower in the Inner Ward to lean outwards at an angle of 10 degrees.[71]

Access to the central island occurred over a drawbridge, through a pair of gatehouses on the eastern side. Caerphilly Castle's Inner East Gatehouse, based on the gatehouse built at Tonbridge in the 1250s, reinforced a trend in gatehouse design across England and Wales.[72] Sometimes termed a keep-gatehouse, the fortification had both exterior and interior defences, enabling it to be defended even if the perimeter of the castle was breached.[73] Two huge towers flanked the gatehouse on either side of an entrance that was protected by portcullises and murder-holes.[74] The substantial size of the gatehouse allowed it to be used for accommodation as well as defence and it was comfortably equipped on a grand scale, probably for the use of the castle constable and his family.[75] Another pair of gatehouses protected the west side.[76]

Inside the inner ward was the castle's Great Hall and accommodation. Caerphilly was built with fashionable, high-status accommodation, similar to that built around the same time in Chepstow Castle.[77] In the medieval period the Great Hall would have been subdivided with wooden screens, colourful decorations, with rich, detailed carving and warmed by a large, central fireplace.[78] Some carved medieval corbels in the shape of male and female heads survive in the hall today, possibly depicting the royal court in the 1320s, including Edward II, Isabella of France, Hugh Despenser and Eleanor de Clare.[79] To the east of the Great Hall was the castle chapel, positioned above the buttery and pantry.[80] On the west side of the hall were the castle's private apartments, two solar blocks with luxurious fittings.[81]

Beyond the central island was the Western Island, probably reached by drawbridges.[76] The island is called Y Weringaer or Caer y Werin in Welsh, meaning "the people's fort", and may have been used by the town of Caerphilly for protection during conflicts.[82] On the north-west side of the Western Island was the site of the former Roman fort, enclosing around 3 acres (1.2 ha), and the remains of the 17th-century civil-war fortification built on the same location.[76]

In popular culture

The long-running British television show Doctor Who chose Caerphilly Castle as a filming location for several episodes, including "The End of Time" in 2009, "The Vampires in Venice" in 2010, two parter "The Rebel Flesh" and "The Almost People" in 2011; “Robot of Sherwood" in 2014 and “Heaven Sent” in 2015. For "The End of Time", producers used the residential quarters of the East Gatehouse, Constable's Hall and Braose Gallery for the filming of a dungeon in the fictional Broadfell Prison.[83]

See also

- Castles in Great Britain and Ireland

- List of castles in Wales

- Castell Coch, also restored by the Marquesses of Bute

Notes

- ^ a b c Cadw. "Caerphilly Castle (13539)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b Cadw. "Caerphilly Castle (GM002)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b Brown 2004, p. 81

- ^ Pounds 1994, p. 165

- ^ Carpenter 2004, p. 110

- ^ Prior 2006, p. 141; Carpenter 2004, p. 110

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 5

- ^ a b Renn 2002, p. 6

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 7

- ^ Carpenter 2004, pp. 384–386

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 7–8

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 8

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 9

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 4, 9

- ^ a b c d Renn 2002, pp. 11–12

- ^ Pounds 1994, pp. 166, 176

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 9–10

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 10, 13

- ^ a b c d Renn 2002, p. 10

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 13

- ^ a b Renn 2002, p. 14

- ^ a b c Prestwich 2010, p. 2

- ^ a b c Renn 2002, p. 15

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 15, 20; "Caerphilly Castle (94497)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Renn 2002, p. 16

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 17

- ^ a b Renn 2002, p. 18

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 18, 41; Newman 2001, p. 169

- ^ "Great Archaeological Sites in Caerphilly - 6. CAERPHILLY CASTLE" (PDF). Glamorgan-Gwent Archaeological Trust.

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 18–19

- ^ a b c d Renn 2002, p. 19

- ^ Davies 1990, pp. 68–69

- ^ a b Newman 2001, p. 169

- ^ Bradley, Arthur Granville (2020). Owen Glyndwr, Outlook Verlag GmbH, Germany, p. 158

- ^ The Bell at Caerleon, Owain Glyndwr, Internet Archive, 2012

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 20

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 20–21

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 21

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 22; Goodall 2011, p. 192

- ^ a b Renn 2002, p. 21; Newman 2001, p. 169

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 22; Lowry 2006, p. 26

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 22, 47

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 22, 35

- ^ a b Renn 2002, p. 22

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 22; Davies 1981, pp. 26–27, 29

- ^ Davies 1981, p. 75

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 22; Davies 1981, p. 30

- ^ a b c Renn 2002, p. 23

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 23; Davies 1981, p. 75

- ^ Davies 1981, pp. 29–30

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 23; Davies 1981, p. 30

- ^ "Background Paper: Tourism, 2008" (PDF). Caerphilly County Borough. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ "Weddings and wedding photography". Cadw. Cadw. Archived from the original on 13 August 2018. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 24–25

- ^ Clark 1852, pp. 1, 3; Hull 2009, p. 73

- ^ Newman 2001, p. 167; Clark 1852, pp. 1, 3

- ^ Spurgeon 1983, p. 214

- ^ King 1991, pp. 118–119; Pounds 1994, p. 165

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 28; Spurgeon 1983, p. 217

- ^ a b Renn 2002, p. 29

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 29, 31

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 28–29

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 31

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 32–33

- ^ a b Renn 2002, pp. 8–9

- ^ Wiggins 2003, pp. 13; Brown 2004, p. 81

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 34

- ^ King 1991, pp. 112–113; Renn 2002, p. 35

- ^ King 1991, p. 112

- ^ Pounds 1994, p. 165; King 1991, p. 113

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 35

- ^ King 1991, pp. 118–119; Goodall 2011, pp. 193; Renn 2002, p. 36

- ^ King 1991, p. 118

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 38–39

- ^ King 1991, p. 118; Renn 2002, pp. 38–39

- ^ a b c Renn 2002, p. 47

- ^ Pounds 1994, pp. 140–141

- ^ Renn 2002, pp. 39–43

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 43

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 41

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 45

- ^ Renn 2002, p. 48

- ^ "Caerphilly Castle". BBC: Doctor Who in Wales. BBC. 27 April 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

Bibliography

- Brown, R. Allen (2004). Allen Brown's English Castles. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. doi:10.1017/9781846152429. ISBN 978-1-84383-069-6.

- Carpenter, David (2004). The Struggle for Mastery: the Penguin History of Britain 1066–1284. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014824-4.

- Clark, George T. (1852). A Description and History of the Castles of Kidwelly and Caerphilly, and of Castell Coch. London, UK: W. Pickering. OCLC 13015278.

- Davies, John (1981). Cardiff and the Marquesses of Bute. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-2463-9.

- Davies, R. R. (1990). Domination and Conquest: the Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Wales, 1100–1300. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-02977-3.

- Goodall, John (2011). The English Castle. New Haven, US and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11058-6.

- Hull, Lisa (2009). Understanding the Castle Ruins Of England And Wales: How to Interpret the Meaning of Masonry and Earthworks. Jefferson, US: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3457-2.

- King, D. J. Cathcart (1991). The Castle in England and Wales. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00350-6.

- Lowry, Bernard (2006). Discovering Fortifications: From the Tudors to the Cold War. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0651-6.

- Newman, John (2001). The Buildings of Wales: Glamorgan. London, UK: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-071056-4.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Prestwich, Michael (2010). "Edward I and Wales". In Williams, Diane; Kenyon, John (eds.). The Impact of Edwardian Castles in Wales. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books. pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-1-84217-380-0.

- Prior, Stuart (2006). A Few Well-Positioned Castles: the Norman Art of War. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-3651-7.

- Renn, Derek (2002). Caerphilly Castle. Cardiff, UK: Cadw. ISBN 978-1-85760-082-7.

- Spurgeon, Jack (1983). "The Castles of Glamorgan: Some Sites and Theories of General Interest". Château Gaillard: Études de castellologie médiévale. 8: 203–226.

- Wiggins, Kenneth (2003). Siege Mines and Underground Warfare. Princes Risborough, UK: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0547-2.