Cabeza la Vaca

Cabeza la Vaca | |

|---|---|

Panoramic view of Cabeza la Vaca | |

| Coordinates: 38°05′N 6°25′W / 38.083°N 6.417°W | |

| Country | Spain |

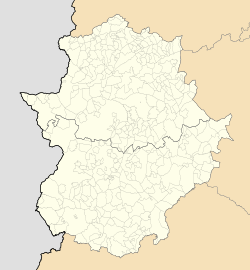

| Autonomous community | Extremadura |

| Province | Badajoz |

| Comarca | Tentudía |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Luis David Zapata Macías (PSOE) |

| Area | |

• Total | 64 km2 (25 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 759 m (2,490 ft) |

| Population (2023)[3] | |

• Total | 1,272 |

| • Density | 20/km2 (51/sq mi) |

| Demonym | cabezalavaqueño/a |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

Cabeza la Vaca is a municipality located in the province of Badajoz, Extremadura, Spain. The economy of the municipality is based on agriculture. The surroundings of the area have thousands of evergreen oaks, olive trees, pine trees and leafy scrubland.

Economy

The economy is based on agriculture, with the breeding of pigs, goats, and sheep being common. Pork and pork products are made here like a variety of sausages such as red sausage. Other food items produced here are black pudding, eggs, green ham, cheeses, and vegetable preserves. Chestnuts, acorns, and cork are also produced.

History

In the Iron Age, this region, like all of the south of Extremadura, where Cabeza la Vaca is located, was inhabited by Celtic people known as the Celtici, but they were also on the border with the Turduli and Turdetanian (tartessian derived) who were located in the southeast. Throughout the second century B.C., the Roman conquest and settlement in the south of Extremadura displaced the Celtic languages around this zone. It is possible the region which nowadays is Cabeza la Vaca may enjoy a period of prosperity as the Roman road Ruta de Plata vía (Silver way in English) is close up connecting the south and north of the Iberian Peninsula. Roman coins have been found around Cabeza la Vaca by farmers when plowing the ground. Rome maintained control through to the 5th century. The end of the Roman rule enabled the Visigothic period. In other parts of the peninsula, this first domain meant a stagnation stage; nevertheless judging by the number of scripts and remains found around the zone and in the same village (reused elements on fountains or columns), this epoch was important for those lands.

The Muslim conquest, between 711 and 716, did not mean the end of the Christianity. In this mountainous, steep and craggy landscapes there were resistors through to the 9th century, then the zone was depopulated, hence the scant remains related to the Muslim and lack of continuity of Cabeza la Vaca with other previous settlements. After the Christian reconquest in the first half of the twelfth century by the Kingdom of Lion and the order of Santiago, around 1230, some huts and cabins, perhaps related to unknown and razed town from the Visigothic epoch and survivors of the Muslim domain, were gradually attracting settlers from the North, until the end of century the location was renamed to Cabeza de la Vaca de León, starting out the modern history of the town. The language of Lion spread through Extremadura, however the Castilian was imposed in the 14th century. The proximity of another Spanish kingdom, Portugal, along with civil wars within Castilla y Leon and terrible plagues led to instability through to the 15th century, when Cabeza de la Vaca consolidated firmly.

The town was closely linked to the conquest of America and to the Kingdom of Seville from the late 15th century. Among the personages more important the village highlights Diego María de la Tordoya illustrious neighbor Cow Head, born probably in the decade of 1460-1470, was one of the companions of Columbus on the first expedition to the New World, and died there. On the other hand, it finds some movements of population at the Archive of Indies, specially in the 17th century toward New Spain and Peru.

The 17th is marked by the collapse of the economic system based on old almost medieval structures, and above all by the conflict with Portugal, which broke the unit of Spain. Whereas, the 18th century was characterized by growth. A lot of lands around Cabeza la Vaca were used for farming and specially livestock, according as the religious orders lost strength, configuring the current economic model of the village. The confiscations from the 19th century intensified this process, but the lands fell into fewer hands. The society of Cabeza la Vaca divided into farmers, owners of properties, and agricultural laborers. This, coupled with the population growth, caused profound social inequalities. Yet the second half of this century had relative prosperity, because the agricultural economy shifted gradually from a communal village to a more efficient private farm-based agriculture; nevertheless, there were less need for manual labor on the farm, so many went to the cities.

In 1905 the town reached over 5,000 inhabitants, but the population then gradually declined. Too much population for a backward economic and especially poorly organized area. Since the 1920s migration toward the near zones or Badajoz, Seville and Madrid appeared, which intensified from the 1950s to the 1970s, when six in ten people emigrated, also toward other regions like Barcelona or Valencia. Remittances from emigrants became the main source of wealth throughout the century. Another event within the century was the Spanish Civil War. Franco's troops entered with little resistance into a village terrified by the excesses of the Republicans such as the confiscation of food or the burning of Churches in nearby towns. But, on the other hand, the 1940s were years of repression too by the Guardia Civil, with rebels in near mountains and crags to Cabeza La Vaca until well into the 1950s.

From the 1950s until the end of the Francoism, the village adopted the widespread use of electricity, and since the early 1980s, the water supply, inasmuch as people came to the fountains to pick up the water. From the mid 1980s, Cabeza la Vaca, much like the Tentudia region, transformed from a stagnant rural society to a service society.

Art

Among the main attractions, besides its nature, is the historic monument called the Cross of the Rollo from the 16th century when the country was ruled by Felipe II. Other main attractions are the Fontanilla, which is in an early Gothic style created in 1339; or the local church from the 14th century with its belfry from the 18th century. Also, there is a bullring and clock tower from the 19th century located in the municipality.

References

- ^ "Corporación municipal". Ayuntamiento de Cabeza la Vaca (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ "Entidades Locales". ssweb.seap.minhap.es. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

- ^ "Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (Spanish Statistical Institute)". www.ine.es. Retrieved 17 August 2024.

External links