Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms | |

|---|---|

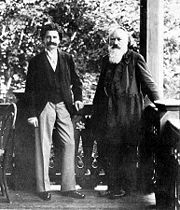

Brahms in 1889 | |

| Born | 7 May 1833 |

| Died | 3 April 1897 (aged 63) |

| Occupations |

|

| Works | List of compositions |

Johannes Brahms (/brɑːmz/; German: [joˈhanəs ˈbʁaːms] ⓘ; 7 May 1833 – 3 April 1897) was a German composer, virtuoso pianist, and conductor of the mid-Romantic period. His music is noted for its rhythmic vitality and freer treatment of dissonance, often set within studied yet expressive contrapuntal textures. He adapted the traditional structures and techniques of a wide historical range of earlier composers. His œuvre includes four symphonies, four concertos, a Requiem, much chamber music, and hundreds of folk-song arrangements and Lieder, among other works for symphony orchestra, piano, organ, and choir.

Born to a musical family in Hamburg, Brahms began composing and concertizing locally in his youth. He toured Central Europe as a pianist in his adulthood, premiering many of his own works and meeting Franz Liszt in Weimar. Brahms worked with Ede Reményi and Joseph Joachim, seeking Robert Schumann's approval through the latter. He gained both Robert and Clara Schumann's strong support and guidance. Brahms stayed with Clara in Düsseldorf, becoming devoted to her amid Robert's insanity and institutionalization. The two remained close, lifelong friends after Robert's death. Brahms never married, perhaps in an effort to focus on his work as a musician and scholar. He was a self-conscious, sometimes severely self-critical composer.

Though innovative, his music was considered relatively conservative within the polarized context of the War of the Romantics, an affair in which Brahms regretted his public involvement. His compositions were largely successful, attracting a growing circle of supporters, friends, and musicians. Eduard Hanslick celebrated them polemically as absolute music, and Hans von Bülow even cast Brahms as the successor of Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven, an idea Richard Wagner mocked. Settling in Vienna, Brahms conducted the Singakademie and Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, programming the early and often "serious" music of his personal studies. He considered retiring from composition late in life but continued to write chamber music, especially for Richard Mühlfeld.

Brahms saw his music become internationally important in his own lifetime. His contributions and craftsmanship were admired by his contemporaries like Antonín Dvořák, whose music he enthusiastically supported, and a variety of later composers. Max Reger and Alexander Zemlinsky reconciled Brahms's and Wagner's often contrasted styles. So did Arnold Schoenberg, who emphasized Brahms's "progressive" side. He and Anton Webern were inspired by the intricate structural coherence of Brahms's music, including what Schoenberg termed its developing variation. It remains a staple of the concert repertoire, continuing to influence composers into the 21st century.

Biography

Youth (1833–1850)

Upbringing

Brahms's father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was from the town of Heide in Holstein.[1][a] Against his family's will, Johann Jakob pursued a career in music, arriving in Hamburg at age 19.[1] He found work playing double bass for jobs; he also played in a sextet in the Alster-pavilion in Hamburg's Jungfernstieg.[3] In 1830, Johann Jakob was appointed as a horn player in the Hamburg militia.[4] He married Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen the same year.[5] A middle-class seamstress 17 years his senior, she enjoyed writing letters and reading despite an apparently limited education.[6]

Johannes Brahms was born in 1833. His sister Elisabeth (Elise) had been born in 1831 and a younger brother Fritz Friedrich was born in 1835.[7][b] The family then lived in poor apartments in the Gängeviertel quarter of Hamburg and struggled economically.[9] (Johann Jakob even considered emigrating to the United States when an impresario, recognizing Johannes's talent, promised them fortune there.)[10] Eventually Johann Jakob became a musician in the Philharmonisches Staatsorchester Hamburg playing double bass, horn, and flute.[11] For enjoyment, he played first violin in string quartets.[11] The family moved over the years to ever better accommodation in Hamburg.[12]

Training

Johann Jakob gave his son his first musical training; Johannes also learnt to play the violin and the basics of playing the cello. From 1840 he studied piano with Otto Friedrich Willibald Cossel. Cossel complained in 1842 that Brahms "could be such a good player, but he will not stop his never-ending composing."

At the age of 10, Brahms made his debut as a performer in a private concert including Beethoven's quintet for piano and winds Op. 16 and a piano quartet by Mozart. He also played as a solo work an étude of Henri Herz. By 1845 he had written a piano sonata in G minor.[13] His parents disapproved of his early efforts as a composer, feeling that he had better career prospects as a performer.[14]

From 1845 to 1848 Brahms studied with Cossel's teacher, the pianist and composer Eduard Marxsen. Marxsen had been a personal acquaintance of Beethoven and Schubert, admired the works of Mozart and Haydn, and was a devotee of the music of J. S. Bach. Marxsen conveyed to Brahms the tradition of these composers and ensured that Brahms's own compositions were grounded in that tradition.[15]

Recitals

In 1847 Brahms made his first public appearance as a solo pianist in Hamburg, playing a fantasy by Sigismund Thalberg. His first full piano recital, in 1848, included a fugue by Bach as well as works by Marxsen and contemporary virtuosi such as Jacob Rosenhain. A second recital in April 1849 included Beethoven's Waldstein sonata and a waltz fantasia of his own composition and garnered favourable newspaper reviews.[16]

Persistent stories of the impoverished adolescent Brahms playing in bars and brothels have only anecdotal provenance,[17] and many modern scholars dismiss them; the Brahms family was relatively prosperous, and Hamburg legislation very strictly forbade music in, or the admittance of minors to, brothels.[18][19]

Juvenilia

Brahms's juvenilia comprised piano music, chamber music and works for male voice choir. Under the pseudonym 'G. W. Marks', some piano arrangements and fantasies were published by the Hamburg firm of Cranz in 1849. The earliest of Brahms's works which he acknowledged (his Scherzo Op. 4 and the song Heimkehr Op. 7 no. 6) date from 1851. However, Brahms was later assiduous in eliminating all his juvenilia. Even as late as 1880, he wrote to his friend Elise Giesemann to send him his manuscripts of choral music so that they could be destroyed.[20]

Early adulthood (1850–1862)

Collaboration and travel

In 1850 Brahms met the Hungarian violinist Ede Reményi and accompanied him in a number of recitals over the next few years. This was his introduction to "gypsy-style" music such as the csardas, which was later to prove the foundation of his most lucrative and popular compositions, the two sets of Hungarian Dances (1869 and 1880).[21][22] 1850 also marked Brahms's first contact (albeit a failed one) with Robert Schumann; during Schumann's visit to Hamburg that year, friends persuaded Brahms to send the former some of his compositions, but the package was returned unopened.[23]

In 1853 Brahms went on a concert tour with Reményi, visiting the violinist and composer Joseph Joachim at Hanover in May. Brahms had earlier heard Joachim playing the solo part in Beethoven's violin concerto and been deeply impressed.[24] Brahms played some of his own solo piano pieces for Joachim, who remembered fifty years later: "Never in the course of my artist's life have I been more completely overwhelmed".[25] This was the beginning of a friendship which was lifelong, albeit temporarily derailed when Brahms took the side of Joachim's wife in their divorce proceedings of 1883.[26]

Brahms admired Joachim as a composer, and in 1856 they were to embark on a mutual training exercise to improve their skills in (in Brahms's words) "double counterpoint, canons, fugues, preludes or whatever".[27] Bozarth notes that "products of Brahms's study of counterpoint and early music over the next few years included "dance pieces, preludes and fugues for organ, and neo-Renaissance and neo-Baroque choral works".[28]

After meeting Joachim, Brahms and Reményi visited Weimar, where Brahms met Franz Liszt, Peter Cornelius, and Joachim Raff, and where Liszt performed Brahms's Op. 4 Scherzo at sight. Reményi claimed that Brahms then slept during Liszt's performance of his own Sonata in B minor; this and other disagreements led Reményi and Brahms to part company.[29]

The Schumanns and Leipzig

Brahms visited Düsseldorf in October 1853, and, with a letter of introduction from Joachim,[30] was welcomed by the Schumanns. Robert, greatly impressed and delighted by the 20-year-old's talent, published an article entitled "Neue Bahnen" ("New Paths") in the 28 October issue of the journal Neue Zeitschrift für Musik nominating Brahms as one who was "fated to give expression to the times in the highest and most ideal manner".[31]

This praise may have aggravated Brahms's self-critical standards of perfection and dented his confidence. He wrote to Schumann in November 1853 that his praise "will arouse such extraordinary expectations by the public that I don't know how I can begin to fulfil them".[32] While in Düsseldorf, Brahms participated with Schumann and Schumann's pupil Albert Dietrich in writing a movement each of a violin sonata for Joachim, the "F-A-E Sonata", the letters representing the initials of Joachim's personal motto Frei aber einsam ("Free but lonely").[33]

Schumann's accolade led to the first publication of Brahms's works under his own name. Brahms went to Leipzig where Breitkopf & Härtel published his Opp. 1–4 (the Piano Sonatas nos. 1 and 2, the Six Songs Op. 3, and the Scherzo Op. 4), whilst Bartholf Senff published the Third Piano Sonata Op. 5 and the Six Songs Op. 6. In Leipzig, he gave recitals including his own first two piano sonatas, and met with Ferdinand David, Ignaz Moscheles, and Hector Berlioz, among others.[28][34]

After Schumann's attempted suicide and subsequent confinement in a mental sanatorium near Bonn in February 1854 (where he died of pneumonia in 1856), Brahms based himself in Düsseldorf, where he supported the household and dealt with business matters on Clara's behalf. Clara was not allowed to visit Robert until two days before his death, but Brahms was able to visit him and acted as a go-between.

Brahms began to feel deeply for Clara, who to him represented an ideal of womanhood. But he was conflicted about their romantic association and resisted it, choosing the life of a bachelor in an apparent effort to focus on his craft.[35] Nonetheless, their intensely emotional relationship lasted until Clara's death. In June 1854 Brahms dedicated to Clara his Op. 9, the Variations on a Theme of Schumann.[28] Clara continued to support Brahms's career by programming his music in her recitals.[36]

Early compositions, reception, and polemics

After the publication of his Op. 10 Ballades for piano, Brahms published no further works until 1860. His major project of this period was the Piano Concerto in D minor, which he had begun as a work for two pianos in 1854 but soon realized needed a larger-scale format. Based in Hamburg at this time, he gained, with Clara's support, a position as musician to the tiny court of Detmold, the capital of the Principality of Lippe, where he spent the winters of 1857 to 1860 and for which he wrote his two Serenades (1858 and 1859, Opp. 11 and 16). In Hamburg he established a women's choir for which he wrote music and conducted. To this period also belong his first two Piano Quartets (Op. 25 and Op. 26) and the first movement of the third Piano Quartet, which eventually appeared in 1875.[28]

The end of the decade brought professional setbacks for Brahms. The premiere of the First Piano Concerto in Hamburg on 22 January 1859, with the composer as soloist, was poorly received. Brahms wrote to Joachim that the performance was "a brilliant and decisive – failure ... [I]t forces one to concentrate one's thoughts and increases one's courage ... But the hissing was too much of a good thing ..."[37] At a second performance, audience reaction was so hostile that Brahms had to be restrained from leaving the stage after the first movement.[38] As a consequence of these reactions Breitkopf and Härtel declined to take on his new compositions. Brahms consequently established a relationship with other publishers, including Simrock, who eventually became his major publishing partner.[28]

Brahms further made an intervention in 1860 in the debate on the future of German music which seriously misfired. Together with Joachim and others, he prepared an attack on Liszt's followers, the so-called "New German School" (although Brahms himself was sympathetic to the music of Richard Wagner, the School's leading light). In particular they objected to the rejection of traditional musical forms and to the "rank, miserable weeds growing from Liszt-like fantasias". A draft was leaked to the press, and the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik published a parody which ridiculed Brahms and his associates as backward-looking. Brahms never again ventured into public musical polemics.[39]

Failed aspirations

Brahms's personal life was also troubled. In 1859 he became engaged to Agathe von Siebold. The engagement was soon broken off, but even after this Brahms wrote to her: "I love you! I must see you again, but I am incapable of bearing fetters. Please write me ... whether ... I may come again to clasp you in my arms, to kiss you, and tell you that I love you." They never saw one another again, and Brahms later confirmed to a friend that Agathe was his "last love".[40]

Brahms had hoped to be given the conductorship of the Hamburg Philharmonic, but in 1862 this post was given to baritone Julius Stockhausen. Brahms continued to hope for the post. But he demurred when he was finally offered the directorship in 1893, as he had "got used to the idea of having to go along other paths".[41]

Maturity (1862–1876)

Move to Vienna

In autumn 1862 Brahms made his first visit to Vienna, staying there over the winter. Although Brahms entertained the idea of taking up conducting posts elsewhere, he based himself increasingly in Vienna and soon made it his home. In 1863, he was appointed conductor of the Wiener Singakademie. He surprised his audiences by programming many works by the early German masters such as Heinrich Schütz and J. S. Bach, and other early composers such as Giovanni Gabrieli; more recent music was represented by works of Beethoven and Felix Mendelssohn. Brahms also wrote works for the choir, including his Motet, Op. 29. Finding however that the post encroached too much of the time he needed for composing, he left the choir in June 1864.[42]

From 1864 to 1876 he spent many of his summers in Lichtental, where Clara Schumann and her family also spent some time. His house in Lichtental, where he worked on many of his major compositions including A German Requiem and his middle-period chamber works, is preserved as a museum.[43]

Wagner and his circle

In Vienna Brahms became an associate of two close members of Wagner's circle, his earlier friend Peter Cornelius and Karl Tausig, and of Joseph Hellmesberger Sr. and Julius Epstein, respectively the Director and head of violin studies, and the head of piano studies, at the Vienna Conservatoire. Brahms's circle grew to include the notable critic (and opponent of the 'New German School') Eduard Hanslick, the conductor Hermann Levi and the surgeon Theodor Billroth, who were to become among his greatest advocates.[44][45]

In January 1863 Brahms met Richard Wagner for the first time, for whom he played his Handel Variations Op. 24, which he had completed the previous year. The meeting was cordial, although Wagner was in later years to make critical, and even insulting, comments on Brahms's music.[46] Brahms however retained at this time and later a keen interest in Wagner's music, helping with preparations for Wagner's Vienna concerts in 1862/63,[45] and being rewarded by Tausig with a manuscript of part of Wagner's Tannhäuser (which Wagner demanded back in 1875).[47] The Handel Variations also featured, together with the first Piano Quartet, in his first Viennese recitals, in which his performances were better received by the public and critics than his music.[48]

Requiem and personal beliefs

In February 1865 Brahms's mother died, and he began to compose his large choral work A German Requiem, Op. 45, of which six movements were completed by 1866. Premieres of the first three movements were given in Vienna, but the complete work was first given in Bremen in 1868 to great acclaim. A seventh movement (the soprano solo "Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit") was added for the equally successful Leipzig premiere (February 1869). The work went on to receive concert and critical acclaim throughout Germany and also in England, Switzerland and Russia, marking effectively Brahms's arrival on the world stage.[45]

Baptised into the Lutheran church as an infant and confirmed at age fifteen in St. Michael's Church,[49] Brahms has been described as an agnostic and a humanist.[50] The devout Catholic Antonín Dvořák wrote in a letter: "Such a man, such a fine soul – and he believes in nothing! He believes in nothing!"[51] When asked by conductor Karl Reinthaler to add additional explicitly religious text to his German Requiem, Brahms is reported to have responded, "As far as the text is concerned, I confess that I would gladly omit even the word German and instead use Human; also with my best knowledge and will I would dispense with passages like John 3:16. On the other hand, I have chosen one thing or another because I am a musician, because I needed it, and because with my venerable authors I can't delete or dispute anything. But I had better stop before I say too much."[52]

Mounting successes and failed romance

Brahms also experienced at this period popular success with works such as his first set of Hungarian Dances (1869), the Liebeslieder Waltzes, Op. 52, (1868/69), and his collections of lieder (Opp. 43 and 46–49).[45] Following such successes he finally completed a number of works that he had wrestled with over many years such as the cantata Rinaldo (1863–1868), his first two string quartets Op. 51 nos. 1 and 2 (1865–1873), the third piano quartet (1855–1875), and most notably his first symphony which appeared in 1876, but which had been begun as early as 1855.[53][54]

During 1869, Brahms felt himself falling in love with the Schumanns' daughter Julie (then aged 24 to his 36). He did not declare himself. When later that year Julie's engagement to Count Marmorito was announced, he wrote and gave to Clara the manuscript of his Alto Rhapsody (Op. 53). Clara wrote in her diary that "he called it his wedding song" and noted "the profound pain in the text and the music".[55]

From 1872 to 1875, Brahms was director of the concerts of the Vienna Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, where he ensured that the orchestra was staffed only by professionals. He conducted a repertoire noted and criticized for its emphasis on early and often "serious" music, running from Isaac, Bach, Handel, and Cherubini to the nineteenth century composers who were not of the New German School. Among these were Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Joachim, Ferdinand Hiller, Max Bruch and himself (notably his large scale choral works, the German Requiem, the Alto Rhapsody, and the patriotic Triumphlied, Op. 55, which celebrated Prussia's victory in the 1870/71 Franco-Prussian War).[54] 1873 saw the premiere of his orchestral Variations on a Theme by Haydn, originally conceived for two pianos, which has become one of his most popular works.[54][56]

Success (1876–1889)

First symphonies and orchestral music

Brahms's First Symphony, Op. 68, appeared in 1876, though it had been begun (and a version of the first movement had been announced by Brahms to Clara and to Albert Dietrich) in the early 1860s. During the decade it evolved very gradually; the finale may not have begun its conception until 1868.[57] Brahms was cautious and typically self-deprecating about the symphony during its creation, writing to his friends that it was "long and difficult", "not exactly charming" and, significantly, "long and in C Minor", which, as Richard Taruskin points out, made it clear "that Brahms was taking on the model of models [for a symphony]: Beethoven's Fifth."[58]

Despite the warm reception the First Symphony received, Brahms remained dissatisfied and extensively revised the second movement before the work was published. There followed a succession of well-received orchestral works: the Second Symphony Op. 73 (1877), the Violin Concerto Op. 77 (1878; dedicated to Joachim, who was consulted closely during its composition), and the Academic Festival Overture (written following the conferring of an honorary degree by the University of Breslau) and Tragic Overture of 1880.

Fame, criticism, and Dvořák

In May 1876, Cambridge University offered to grant honorary degrees of Doctor of Music to both Brahms and Joachim, provided that they composed new pieces as "theses" and were present in Cambridge to receive their degrees. Brahms was averse to traveling to England and requested to receive the degree 'in absentia', offering as his thesis the previously performed (November 1876) symphony.[59] But of the two, only Joachim went to England and was granted a degree. Brahms "acknowledged the invitation" by giving the manuscript score and parts of his First Symphony to Joachim, who led the performance at Cambridge 8 March 1877 (English premiere).[60]

The commendation of Brahms by Breslau as "the leader in the art of serious music in Germany today" led to a bilious comment from Wagner in his essay "On Poetry and Composition": "I know of some famous composers who in their concert masquerades don the disguise of a street-singer one day, the hallelujah periwig of Handel the next, the dress of a Jewish Czardas-fiddler another time, and then again the guise of a highly respectable symphony dressed up as Number Ten" (referring to Brahms's First Symphony as a putative tenth symphony of Beethoven).[61]

Brahms was now recognised as a major figure in the world of music. He had been on the jury which awarded the Vienna State Prize to the (then little-known) composer Antonín Dvořák three times, first in February 1875, and later in 1876 and 1877, and had successfully recommended Dvořák to his publisher, Simrock. The two men met for the first time in 1877, and Dvořák dedicated to Brahms his String Quartet, Op. 34 of that year.[62] He also began to be the recipient of a variety of honours: Ludwig II of Bavaria awarded him the Maximilian Order for Science and Art in 1874, and the music-loving Duke George of Meiningen awarded him the Commander's Cross of the Order of the House of Meiningen in 1881.[63]

At this time Brahms also chose to change his image. Having been always clean-shaven, in 1878 he surprised his friends by growing a beard, writing in September to the conductor Bernhard Scholz: "I am coming with a large beard! Prepare your wife for a most awful sight."[64] The singer George Henschel recalled that after a concert "I saw a man unknown to me, rather stout, of middle height, with long hair and a full beard. In a very deep and hoarse voice he introduced himself as 'Musikdirektor Müller' ... an instant later, we all found ourselves laughing heartily at the perfect success of Brahms's disguise." The incident also displays Brahms's love of practical jokes.[65]

In 1882 Brahms completed his Piano Concerto No. 2, Op. 83, dedicated to his teacher Marxsen.[54] Brahms was invited by Hans von Bülow to undertake a premiere of the work with the Meiningen Court Orchestra. This was the beginning of his collaboration with Meiningen and with von Bülow, who was to rank Brahms as one of the 'Three Bs'; in a letter to his wife he wrote: "You know what I think of Brahms: after Bach and Beethoven the greatest, the most sublime of all composers."[66]

Later symphonies and continuing recognition

The following years saw the premieres of his Third Symphony, Op. 90 (1883) and his Fourth Symphony, Op. 98 (1885). Richard Strauss, who had been appointed assistant to von Bülow at Meiningen, and had been uncertain about Brahms's music, found himself converted by the Third Symphony and was enthusiastic about the Fourth: "a giant work, great in concept and invention".[67] Another, but more cautious, supporter from the younger generation was Gustav Mahler, who first met Brahms in 1884 and remained a close acquaintance. He considered Brahms a conservative master who was more turned toward the past than the future. He rated Brahms as technically superior to Anton Bruckner, but more earth-bound than Wagner and Beethoven.[68]

In 1889, Theo Wangemann, a representative of the American inventor Thomas Edison, visited the composer in Vienna and invited him to make an experimental recording. Brahms played an abbreviated version of his first Hungarian Dance and of Josef Strauss's Die Libelle on the piano. Although the spoken introduction to the short piece of music is quite clear, the piano playing is largely inaudible due to heavy surface noise.[69]

In that same year, Brahms was named an honorary citizen of Hamburg.[70]

Old age (1889–1897)

Friendship with J. Strauss

Brahms and Johann Strauss II were acquainted in the 1870s, but their close friendship belongs to the years 1889 and after. Brahms admired much of Strauss's music and encouraged the composer to sign with his publisher Simrock. In autographing a fan for Strauss's wife Adele, Brahms wrote the opening notes of The Blue Danube waltz, adding the words "unfortunately not by Johannes Brahms".[71] He made the effort, three weeks before his death, to attend the premiere of Johann Strauss's operetta Die Göttin der Vernunft (The Goddess of Reason) in March 1897.[71]

Late chamber music and songs

After the successful Vienna premiere of his Second String Quintet, Op. 111 in 1890, the 57-year-old Brahms came to think that he might retire from composition, telling a friend that he "had achieved enough; here I had before me a carefree old age and could enjoy it in peace."[72] He also began to find solace in escorting the mezzo-soprano Alice Barbi and may have proposed to her (she was only 28).[73] His admiration for Richard Mühlfeld, clarinettist with the Meiningen orchestra, revived his interest in composing and led him to write the Clarinet Trio, Op. 114 (1891); Clarinet Quintet, Op. 115 (1891); and the two Clarinet Sonatas, Op. 120 (1894).

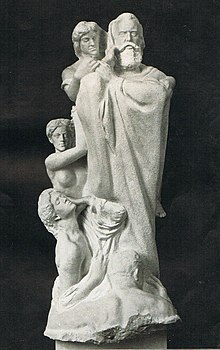

Brahms also wrote at this time his final cycles of piano pieces, Opp. 116–119 and the Vier ernste Gesänge (Four Serious Songs), Op. 121 (1896), which were prompted by the death of Clara Schumann and dedicated to the artist Max Klinger, who was his great admirer.[74] The last of the Eleven Chorale Preludes for organ, Op. 122 (1896) is a setting of "O Welt ich muss dich lassen" ("O world I must leave thee") and the last notes that Brahms wrote.[75] Many of these works were written in his house in Bad Ischl, where Brahms had first visited in 1882 and where he spent every summer from 1889 onwards.[76]

Terminal illness

In the summer of 1896 Brahms was diagnosed with jaundice and pancreatic cancer, and later in the year his Viennese doctor diagnosed him with liver cancer, from which his father Jakob had died.[77] His last public appearance was on 7 March 1897, when he saw Hans Richter conduct his Symphony No. 4; there was an ovation after each of the four movements.[78] His condition gradually worsened and he died on 3 April 1897, in Vienna at the age of 63. Brahms is buried in the Vienna Central Cemetery in Vienna, under a monument designed by Victor Horta with sculpture by Ilse von Twardowski.[79]

Music

Though most of his music is vocal, Brahms's major works are for orchestra, including four symphonies, two piano concertos (No. 1 in D minor; No. 2 in B-flat major), a Violin Concerto, a Double Concerto for violin and cello, and the Academic Festival and Tragic Overtures. He also wrote two Serenades.

His large choral work A German Requiem—not a setting of the liturgical Missa pro defunctis, but a setting of texts which Brahms selected from the Luther Bible—was composed in three major periods of his life. An early version of the second movement was first composed in 1854 after Robert Schumann's attempted suicide (and later used in his first piano concerto). Most of the Requiem was composed after Brahms's mother's death in 1865. He added the fifth movement after the 1868 premiere, and in 1869 the final work was published.

His works in variation form include the Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel and the Paganini Variations, both for solo piano, and the Variations on a Theme by Haydn (now sometimes called the Saint Anthony Variations) in versions for two pianos and for orchestra. The final movement of the Symphony No. 4 is a passacaglia.

His chamber works include three string quartets, two string quintets, two string sextets, a clarinet quintet, a clarinet trio, a horn trio, a piano quintet, three piano quartets, and four piano trios (the A-major trio being published posthumously). He composed several instrumental sonatas with piano, including three for violin, two for cello, and two for clarinet (which were subsequently arranged for viola by the composer). His solo piano works range from his early piano sonatas and ballades to his late sets of character pieces. His Eleven Chorale Preludes, Op. 122, written shortly before his death and published posthumously in 1902, have become an important part of the organ repertoire.

Brahms was an extreme perfectionist, which Schumann's early enthusiasm only exacerbated.[31] He destroyed many early work—including a violin sonata he had performed with Reményi and violinist Ferdinand David—and once claimed to have destroyed 20 string quartets before he issued his official First in 1873.[80] Over the course of several years, he changed an original project for a symphony in D minor into his first piano concerto. In another instance of devotion to detail, he laboured over the official First Symphony for almost fifteen years, from about 1861 to 1876. Even after its first few performances, Brahms destroyed the original slow movement and substituted another before the score was published.

Style, influences, and historiography

The music of Brahms is known for its debts to the Viennese Classical and earlier traditions, including its use of traditional genres and forms (e.g., sonata form). In the shadow of Beethoven, Brahms and his contemporaries increasingly exploited harmonies and emphasized motifs as fundamental structural elements.[81] The music of some of his contemporaries, especially the New German School, was more obviously innovative, virtuosic, and emotional or evocative, often with well defined dramatic or programmatic elements. In this context, many like Hanslick (and more recently Harold C. Schonberg)[82] saw in Brahms a conservative or reactionary champion of tradition and absolute music.

Such views have been variously challenged or qualified. In terms of technique, Brahms's use of developing variation, Carl Dahlhaus argued, was an expository procedure analogous to that of Liszt's and Wagner's modulating sequences.[81] Though Brahms often wrote music without an explicit or public program,[83] in his Symphony No. 4 alone he musically alluded to the second movement of Beethoven's Symphony No. 5, the texted chaconne of Bach's Cantata No. 150, and to Schumann's music, from musical cryptograms of Clara to the Fantasie in C with its use of Beethoven's An die ferne Geliebte, perhaps intending these as ironic, autobiographical reflections on the work's tragic character.[84]

Most of his music was in fact vocal, including hundreds of folk-song arrangements and Lieder[85] often about rural life. As was common from Schubert to Mahler, Brahms faithfully relied on such songs for melodic inspiration in his instrumental music[86] from his very first opus, the Piano Sonata No. 1 (its Andante is based on a Minnesang).[87] Though Brahms never wrote an opera, he was sometimes interested in composing one,[88] and he admired Wagner's music, confining his ambivalence only to the dramaturgical precepts of Wagner's theory.[51][c] In his Symphony No. 3, Brahms alluded to Wagner's Tannhäuser in the first movement (mm. 31–35) and to Götterdämmerung in the second (mm. 108–110).[89]

Brahms considered giving up composition when it seemed that other composers' innovations in extended tonality resulted in the rule of tonality being broken altogether.[citation needed]

Beethoven and the Viennese Classical tradition

Brahms venerated Beethoven; in the composer's home, a marble bust of Beethoven looked down on the spot where he composed, and some passages in his works are reminiscent of Beethoven's style. Brahms's First Symphony bears the influence of Beethoven's Fifth, for example, in struggling toward a C major triumph from C minor. The main theme of the finale of the First Symphony is also reminiscent of the main theme of the finale of Beethoven's Ninth, and when this resemblance was pointed out to Brahms he replied that any dunce[90] could see that. In 1876, when the work was premiered in Vienna, it was immediately hailed as "Beethoven's Tenth". Indeed, the similarity of Brahms's music to that of late Beethoven had first been noted as early as November 1853 in a letter from Albert Dietrich to Ernst Naumann.[91][92]

Brahms loved the classical composers Mozart and Haydn. He especially admired Mozart, so much so that in his final years he reportedly declared Mozart as the greatest composer. On 10 January 1896, Brahms conducted the Academic Festival Overture and both piano concertos in Berlin, and during the following celebration Brahms interrupted Joachim's toast with "Ganz recht; auf Mozart's Wohl" (Quite right; here's Mozart's health).[93] Brahms also compared Mozart with Beethoven to the latter's disadvantage, in a letter to Richard Heuberger in 1896: "Dissonance, true dissonance as Mozart used it, is not to be found in Beethoven. Look at Idomeneo. Not only is it a marvel, but as Mozart was still quite young and brash when he wrote it, it was a completely new thing. You couldn't commission great music from Beethoven since he created only lesser works on commission—his more conventional pieces, his variations and the like."[94] Brahms collected first editions and autographs of Mozart and Haydn's works and edited performing editions.

Early Romantics

Some early Romantic composers had a major influence on Brahms, particularly Schumann, who encouraged Brahms as a young composer. During his stay in Vienna in 1862–63, Brahms became particularly interested in the music of Schubert.[95] The latter's influence may be identified in works by Brahms dating from the period, such as the two piano quartets Op. 25 and Op. 26, and the Piano Quintet, which alludes to Schubert's String Quintet and Grand Duo for piano four hands.[95][96]

Any influence of Chopin and Mendelssohn on Brahms is less obvious. Brahms perhaps alludes to Chopin's Scherzo in B-flat minor in the Scherzo, Op. 4.[97] In the Piano Sonata, Op. 5, scherzo, he may allude to the finale of Mendelssohn's Piano Trio in C minor.[98]

Alte Musik

Brahms looked to older music, with its counterpoint, for inspiration. He studied the music of pre-classical composers, including Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Giovanni Gabrieli, Johann Adolph Hasse, Heinrich Schütz, Domenico Scarlatti, George Frideric Handel, and Johann Sebastian Bach.

His friends included leading musicologists. He co-edited an edition of the works of François Couperin with Friedrich Chrysander. He also edited works by C. P. E. Bach and W. F. Bach.

Peter Phillips heard affinities between Brahms's rhythmically charged, contrapuntal textures and those of Renaissance masters such as Giovanni Gabrieli and William Byrd. Referring to Byrd's Though Amaryllis dance, Philips remarked that "the cross-rhythms in this piece so excited E. H. Fellowes that he likened them to Brahms's compositional style."[99]

Some of Brahms's music is modeled on Baroque sources, especially Bach (e.g., the fugal finale of Cello Sonata No. 1 on Bach's The Art of Fugue, the passacaglia theme of the Fourth Symphony's finale on Bach's Cantata No. 150).

Textures

Brahms was a master of counterpoint. "For Brahms, ... the most complicated forms of counterpoint were a natural means of expressing his emotions," writes Geiringer. "As Palestrina or Bach succeeded in giving spiritual significance to their technique, so Brahms could turn a canon in motu contrario or a canon per augmentationem into a pure piece of lyrical poetry."[100] Writers on Brahms have commented on his use of counterpoint. For example, of Op. 9, Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Geiringer writes that Brahms "displays all the resources of contrapuntal art".[101] In the A major piano quartet Opus 26, Jan Swafford notes that the third movement is "demonic-canonic, echoing Haydn's famous minuet for string quartet called the 'Witch's Round'".[102] Swafford further opines that "thematic development, counterpoint, and form were the dominant technical terms in which Brahms ... thought about music".[103]

Allied to his skill in counterpoint was his subtle handling of rhythm and meter. Bozarth speculates that his contact with Hungarian and gypsy folk music as a teenager led to "his lifelong fascination with the irregular rhythms, triplet figures and use of rubato" in his compositions.[104] The Hungarian Dances are among Brahms's most-appreciated pieces.[105] Michael Musgrave considered that only Stravinsky approached the advancement of his rhythmic thinking.[106]

His use of counterpoint and rhythm is present in A German Requiem, a work that was partially inspired by his mother's death in 1865 (at a time in which he composed a funeral march that was to become the basis of Part Two, "Denn alles Fleisch"), but which also incorporates material from a symphony which he started in 1854 but abandoned following Schumann's suicide attempt. He once wrote that the Requiem "belonged to Schumann". The first movement of this abandoned symphony was re-worked as the first movement of the First Piano Concerto.

Performance practice

Brahms played principally on German and Viennese pianos. In his early years he used a piano made by the Hamburg company Baumgarten & Heins.[107] Later, in 1864, he wrote to Clara about his attraction to instruments by Streicher.[108] In 1873 he received a Streicher piano op. 6713 and kept it in his house until his death.[109] He wrote to Clara: "There [on my Streicher] I always know exactly what I write and why I write one way or another."[108] Another instrument in Brahms's possession was a Conrad Graf piano – a wedding present of the Schumanns, that Clara Schumann later gave to Brahms and which he kept until 1873.[110]

In the 1880s for his public performances Brahms used a Bösendorfer several times. In his Bonn concerts he played on a Steinweg Nachfolgern in 1880 and a Blüthner in 1883. Brahms also used a Bechstein in several of his concerts: 1872 in Würzburg, 1872 in Cologne and 1881 in Amsterdam.[111]

Reception

Brahms looked both backward and forward. His output was often bold in its exploration of harmony and textural elements, especially rhythm. As a result, he influenced composers of both conservative and modernist tendencies.

Brahms' symphonies are prominent in the standard repertoire of symphony orchestras;[112] only Beethoven's are more frequently performed.[113] Brahms's have often been measured against Beethoven's.[113][how?]

Brahms often sent manuscripts to friends Billroth, Elisabeth von Herzogenberg, Joachim, and Clara Schumann for review.[114] They noted its textures and frequent dissonances, which Brahms wrote (to Henschel) that he preferred on the strong beat, "resolve[d] ... lightly and gently!"[114] In 1855, Clara felt Brahms's harshness most distinguished his music from Robert's.[115] Billroth described Brahms's dissonances as "cutting", "toxic", or (in the case of "In stiller Nacht") "divine".[116] In 1855, Joachim noted "steely harshness" in the Benedictus of the Missa canonica, with its "bold independence of the voices".[117] But in 1856 he objected to "extensive harshness" in Geistliches Lied,[117] telling Brahms:

You [are] so used to rough harmonies, of such polyphonic texture ... . ... You cannot ask that of the listener ... art [should] inspire collective delight ... .[117]

Some criticized Brahms's music as overly academic, dense, or muddy.[112] Even Hanslick criticized the First Symphony as academic.[118] (He later praised the "harmonic and contrapuntal art" of the Fourth Symphony's passacaglia.)[118] Elisabeth von Herzogenberg initially considered the Fourth's first movement a "work of [the] brain ... designed too much" (her opinion improved within weeks).[118] Arnold Schoenberg would later defend Brahms: "It is not the heart alone which creates all that is beautiful [or] emotional".[119] Benjamin Britten lost his taste for Brahms's "thickness of texture" and studied expressivity.[120]

Schoenberg and others, among them Theodor W. Adorno and Carl Dahlhaus, sought to advance Brahms's reputation in the early and mid-20th century against the criticisms[clarification needed] of Paul Bekker and Wagner.[121] For Brahms's centenary in 1933, Schoenberg wrote and broadcast an essay "Brahms the Progressive" (rev. 1947, pub. 1950), establishing Brahms's historical continuity (perhaps self-servingly).[122] Schoenberg portrayed him as a forward-looking innovator, somewhat polemically against the image of Brahms as an academic traditionalist.[123] He highlighted Brahms's fondness for motivic saturation and irregularities of rhythm and phrase, terming Brahms's compositional principles "developing variation". In Structural Functions of Harmony (1948), Schoenberg analyzed Brahms's "enriched harmony" and exploration of remote tonal regions.

Influence

Within his lifetime, Brahms's idiom left an imprint on several composers within his personal circle, who strongly admired his music, such as Heinrich von Herzogenberg, Robert Fuchs, and Julius Röntgen, as well as on Gustav Jenner, who was his only formal composition pupil. Antonín Dvořák, who received substantial assistance from Brahms, deeply admired his music and was influenced by it in several works, such as the Symphony No. 7 in D minor and the F minor Piano Trio.

Features of the "Brahms style" were absorbed in a more complex synthesis with other contemporary (chiefly Wagnerian) trends by Hans Rott, Wilhelm Berger, Max Reger and Franz Schmidt, whereas the British composers Hubert Parry and Edward Elgar and the Swede Wilhelm Stenhammar all testified to learning much from Brahms. As Elgar said, "I look at the Third Symphony of Brahms, and I feel like a pygmy."[124] In France, Gabriel Fauré's music showed Brahmsian concern for rhythm and texture; in Russia, Sergei Taneyev was called "the Russian Brahms";[125] and in the United States, Amy Beach's musical textures were noted for their Brahmsian richness.[126]

Ferruccio Busoni's early music shows much Brahmsian influence, and Brahms took an interest in him, though Busoni later tended to disparage Brahms. Towards the end of his life, Brahms offered substantial encouragement to Ernst von Dohnányi and to Alexander von Zemlinsky. Their early chamber works, those of Béla Bartók (who was friendly with Dohnányi), show a thoroughgoing absorption of the Brahmsian idiom.

Second Viennese School

Zemlinsky in turn taught Schoenberg, and Brahms was apparently impressed when in 1897 Zemlinsky showed him drafts of two movements of Schoenberg's early D-major quartet. Webern and later Walter Frisch identified Brahms's influence in the dense, cohesive textures and variation techniques of Schoenberg's first quartet.[127]

In 1937, Schoenberg orchestrated Brahms's Piano Quartet No. 1 as an exercise suggested by Otto Klemperer to break writer's block; Klemperer regarded it as better than the original.[128] (George Balanchine later set it to dance in Brahms–Schoenberg Quartet.)

In Anton Webern's 1933 lectures, posthumously published under the title The Path to the New Music, he claimed Brahms as one who had anticipated the developments of the Second Viennese School. Webern's 1908 Passacaglia, Op. 1, is clearly in part a homage to, and development of, the variation techniques of the passacaglia-finale of Brahms's Fourth Symphony. Ann Scott argued Brahms anticipated the procedures of the serialists by redistributing melodic fragments between instruments, as in the first movement of the Clarinet Sonata, Op. 120, No. 2.[129]

Later composers

Still later composers, like Milton Babbitt, Elliott Carter and György Ligeti paid respect to Brahms in their music, especially in terms of their treatment of meter, motives, rhythm, or texture.[130] More recently, composers like Wolfgang Rihm (e.g., Klavierstück Nr. 6, Brahmsliebewalzer, Ernster Gesang, Das Lesen der Schrift, Symphonie Nähe Fern) and Thomas Adès (e.g., Brahms) also engaged with Brahms's music, often as seen through Schoenberg's "progressive" lens.[131]

Memorials

On 14 September 2000, Brahms was honoured in the Walhalla, a German hall of fame. He was introduced there as the 126th "rühmlich ausgezeichneter Teutscher" [honorably distinguished German] and 13th composer among them, with a bust by sculptor Milan Knobloch.[132]

Notes

- ^ His family name was also sometimes spelled Brahmst or Brams, deriving from Bram, the German word for the shrub broom.[2]

- ^ Fritz also became a pianist; overshadowed by his brother, he emigrated to Caracas in 1867, and later returned to Hamburg as a teacher.[8]

- ^ Wagner harshly criticized Brahms as the latter grew in stature and popularity, but he was enthusiastically receptive of the early Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel.

References

Citations

- ^ a b Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 4.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 7.

- ^ Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 4–5.

- ^ Hofmann 1999, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 3.

- ^ Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 6–9.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Musgrave 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 9–11, 14.

- ^ Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 10, 17.

- ^ a b Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 12.

- ^ Hofmann 1999, pp. 4–8.

- ^ Hofmann 1999, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Hofmann 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 26.

- ^ Hofmann 1999, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Including tales allegedly told by Brahms himself to Clara Schumann and others; see Jan Swafford, "'Aimez-Vous Brahms': An Exchange", The New York Review of Books 18 March 1999, accessed 1 July 2018.

- ^ Swafford 2001, passim.

- ^ Hofmann 1999, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Hofmann 1999, pp. 16, 18–20.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 56, 62.

- ^ Musgrave 1999b, 45.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 49.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 64.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 494–495.

- ^ Musgrave 2000, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d e Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §2: "New Paths"

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 67, 71.

- ^ Gál 1963, p. 7.

- ^ a b Schumann 1988, pp. 199–200

- ^ Avins 1997, p. 24.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §2: "New Paths".

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 180, 182.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 211.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 206–211.

- ^ Musgrave 2000, pp. 52–53

- ^ Musgrave 2000, pp. 27, 31.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 277–279, 283.

- ^ Hofmann & Hofmann 2010, p. 40; "Brahms House", on website of the Schumann Portal, accessed 22 December 2016.

- ^ Musgrave 1999b, 39–41.

- ^ a b c d Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §3 "First maturity"

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 265–269.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 401.

- ^ Musgrave 1999b, 39.

- ^ Musgrave, Michael (September 2001). A Brahms Reader. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09199-1.

- ^ Swafford 2012, p. 327.

- ^ a b Swafford 1999.

- ^ Musgrave 1985, p. 80.

- ^ Becker 1980, pp. 174–179.

- ^ a b c d Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §4, "At the summit"

- ^ Petersen 1983, p. 1.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 383.

- ^ Musgrave 1999b, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Taruskin 2010, p. 694.

- ^ Pascall n.d.

- ^ Anon. 1916, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Taruskin 2010, p. 729.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 444–446.

- ^ Musgrave 1999a, xv; Musgrave 2000, 171; Swafford 1999, 467.

- ^ Hofmann & Hofmann 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Musgrave 2000, pp. 4, 6.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 465–466.

- ^ Musgrave 2000, p. 252.

- ^ Musgrave 2000, pp. 253–254.

- ^ J. Brahms plays excerpt of Hungarian Dance No. 1 (2:10) on YouTube Analysts and scholars remain divided as to whether the voice that introduces the piece is that of Wangemann or of Brahms. A "denoised" version of the recording was produced at Stanford University. "Brahms at the Piano" by Jonathan Berger (CCRMA, Stanford University)

- ^ "Stadt Hamburg Ehrenbürger" website: Dr. phil. h.c. Johannes Brahms (1833–1897) (in German) Retrieved 14 October 2019

- ^ a b Lamb 1975, pp. 869–870

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 568–569.

- ^ Swafford 1999, p. 569.

- ^ "Max Klinger / Johannes Brahms: Engraving, Music and Fantasy". Musée d'Orsay. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Bond 1971, p. 898.

- ^ Hofmann & Hofmann 2010, p. 42.

- ^ Swafford 1999, pp. 614–615.

- ^ Clive, Peter (2006). "Richter, Hans". Brahms and His World: A Biographical Dictionary. Scarecrow Press. p. 361. ISBN 978-1-4617-2280-9.

- ^ Zentralfriedhof group 32a, details

- ^ Bozarth, George S. ""Paths Not Taken: The" Lost" Works of Johannes Brahms."". researchgate.net. Music Review 1989. p. 186.

According to the estimate of Alwin Cranz, a boyhood friend of Brahms, the composer destroyed more than twenty string quartets before publishing the Quartets in C minor and A minor

- ^ a b Dahlhaus 1980, 46–51.

- ^ Parmer 1995, 163n17, quoting Harold C. Schoenberg's The Lives of the Great Composers (New York, 1981) 296.

- ^ Hull 1998, 167–168.

- ^ Hull 1998, 135–137, 137n5, 141–149, 141n9, 146–147n17, 150–157, 156–157n30, 157–168; quoting Eric Sams et al; Parmer 1995, 162n8.

- ^ Parmer 1995, 161.

- ^ Parmer 1995, 162–163.

- ^ Parmer 1995, 162n4, citing Bozarth's "Brahms's Lieder ohne Worte: The 'Poetic' Andantes of the Piano Sonatas".

- ^ Brody 1985, 24–37.

- ^ Parmer 1995, 162n4, citing Robert Bailey's "Musical Language and Structure in the Third Symphony".

- ^ Brahms used the German word "Esel", of which one translation is "donkey" and another is "dunce": Cassell's New German Dictionary, Funk and Wagnalls, New York and London, 1915

- ^ Floros 2010, 80.

- ^ Dietrich, Albert Hermann; Widmann, J. V. (2000). Recollections of Johannes Brahms. Minerva Group. ISBN 978-0-89875-141-3. OCLC 50646747. Retrieved 8 October 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ Spaeth, Sigmund (2020). Stories Behind the World's Great Music. Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 235.

- ^ Fisk, Josiah; Nichols, Jeff, eds. (1997). Composers On Music: Eight Centuries of Writings. University Press of New England. pp. 134–135. ISBN 978-1-55553-279-6.

- ^ a b Webster, James, "Schubert's sonata form and Brahms's first maturity (II)", 19th-Century Music 3(1) (1979), pp. 52–71.

- ^ Tovey, Donald Francis, "Franz Schubert" (1927), rpt. in Essays and Lectures on Music (London, 1949), p. 123. Cf. his similar remarks in "Tonality in Schubert" (1928), rpt. ibid., p. 151.

- ^ Rosen, Charles, "Influence: plagiarism and inspiration", 19th-Century Music 4(2) (1980), pp. 87–100.

- ^ Spanner, H.V. "What is originality?", The Musical Times 93(1313) (1952), pp. 310–311.

- ^ Phillips, P. (2007) sleeve note to English Madrigals, 25th anniversary edition, CD recording, Gimell Records.

- ^ Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 159.

- ^ Geiringer and Geiringer 1982, 210.

- ^ Swafford 2012, p. 159.

- ^ Swafford 2012, p. xviii.

- ^ Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §1, "Formative years".

- ^ Gál 1963, pp. 17, 204.

- ^ Musgrave 1985, p. 269.

- ^ Münster, Robert (2020). "Bernhard und Luise Scholz im Briefwechsel mit Max Kalbeck und Johannes Brahms". In Thomas Hauschke (ed.). Johannes Brahms: Beiträge zu seiner Biographie (in German). Vienna: Hollitzer Verlag. pp. 153–230. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1cdxfs0.14. ISBN 978-3-99012-880-0. S2CID 243190598.

- ^ a b Litzmann, Berthold (1 February 1903). "Clara Schumann von Berthold Litzmann. Erster Band, Mädchenjahre". The Musical Times. 44 (720): 113. doi:10.2307/903152. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 903152.

- ^ Biba, Otto (January 1983). "Ausstellung 'Johannes Brahms in Wien' im Musik Verein". Österreichische Musikzeitschrift. 38 (4–5). doi:10.7767/omz.1983.38.45.254a. S2CID 163496436.

- ^ Frisch & Karnes 2009, p. 78.

- ^ Cai, Camilla (1989). "Brahms's Pianos and the Performance of His Late Works". Performance Practice Review. 2 (1): 59. doi:10.5642/perfpr.198902.01.3. ISSN 1044-1638.

- ^ a b Frisch 2003, xiii.

- ^ a b Frisch 2003, ix.

- ^ a b Floros 2010, 208.

- ^ Floros 2010, 209.

- ^ Floros 2010, 210.

- ^ a b c Floros 2010, 208–209.

- ^ a b c Frisch 2003, 153.

- ^ Frisch 2003, Schoenberg's 1946 "Heart and Brain in Music" essay, quoted 154.

- ^ Musgrave 1985, 269–270.

- ^ Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §6, ¶4–10.

- ^ Musgrave 1999a, xx.

- ^ Kross 1983, 142.

- ^ MacDonald 2001, p. 406.

- ^ Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §6: "Influence and reception".

- ^ Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). "Amy Beach". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Frisch 1984, 164–165, partly quoting Webern's 1912 essay "Schoenberg's Music".

- ^ Maurer Zenck 1999, 183, 191n71.

- ^ Scott, Ann Besser (1995). "Thematic transmutation in the music of Brahms: A matter of musical alchemy". Journal of Musicological Research. 15 (2): 177–206. doi:10.1080/01411899508574717. ISSN 0141-1896.

- ^ Bozarth and Frisch 2001, §6: "Influence and reception"; Musgrave 1985, 269–270.

- ^ Grimes 2018, 523–528, 538–542; Massey 2021, 124–129, citing Venn 2015; Venn 2015, 164–168, 175, 192–193, et passim, citing Adrian Jack's "Brendel's Poems Set to Music" in The Independent (3 July 2001), Hélène Cao's Thomas Adès le voyageur: Devenir compositeur, être musicien (Paris, 2007) 34–35, and Elaine Barkin's "About Some Music of Thomas Adès", Perspectives of New Music 47(1):171–172.

- ^ "Johannes Brahms hält Einzug in die Walhalla". Bayerisches Staatsministerium für Wissenschaft, Forschung und Kunst. 14 September 2000. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

Sources

- Anon. (1916). Programme, Volumes 1916–1917, Boston Symphony Orchestra, pub. 1916

- Avins, Styra, ed. (1997). Johannes Brahms: Life and Letters. Translated by Joseph Eisinger and S. Avins. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816234-6.

- Becker, Heinz (1980). "Brahms, Johannes". In Stanley Sadie (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 3. London: Macmillan. pp. 154–190. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- Bond, Ann (1971). "Brahms Chorale Preludes, Op. 122". The Musical Times. 112 (1543): 898–900. doi:10.2307/955537. JSTOR 955537.

- Bozarth, George S. and Walter Frisch. 2001. "Brahms, Johannes". Grove Music Online (accessed 23 Nov. 2024). doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.51879. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- Brody, Elaine. 1985. "Operas in Search of Brahms". The Opera Quarterly. 3(4):24–37. doi:10.1093/oq/3.4.24.

- Dahlhaus, Carl. 1980. Between Romanticism and Modernism: Four Studies in the Music of the Later Nineteenth Century, trans. Mary Whittall and Arnold Whittall from original in German (Emil Katzbichler, 1974). California Studies in 19th-Century Music Series, gen. ed. Joseph Kerman. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03679-6 (hbk).

- Floros, Constantin. 2010. Johannes Brahms, "Free but Alone": A Life for a Poetic Music, trans. Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch from original in German (Arche Verlag AG, 2010). Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang GmbH. ISBN 978-3-631-61260-6 (hbk).

- Frisch, Walter. 1984. Brahms and the Principle of Developing Variation. California Studies in 19th-Century Music Series, gen. ed. Joseph Kerman. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04700-6 (hbk).

- Frisch, Walter. 2003. Brahms: The Four Symphonies. Yale Music Masterworks Series, gen. ed. and fwd. George B. Stauffer. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Reprint from original in 1996 by Schirmer Books. ISBN 978-0-300-09965-2 (pbk).

- Frisch, Walter; Karnes, Kevin C., eds. (2009). Brahms and His World (revised ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14344-6.

- Grimes, Nicole. 2018. "Brahms as a Vanishing Point in the Music of Wolfgang Rihm: Reflections on Klavierstück Nr. 6". Music Preferred: Essays in Musicology, Cultural History and Analysis, in Honour of Harry White, ed. Lorraine Byrne-Bodley, 523-549. Vienna: Hollitzer. ISBN 978-3-99012-401-7 (hbk).

- Gál, Hans (1963). Johannes Brahms: His Work and Personality. Translated by Joseph Stein. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Hull, Kenneth. 1998. "Allusive Irony in Brahms's Fourth Symphony", 135–168. In Brahms: Biographical, Documentary, and Analytical Studies, Vol. 2, ed. Michael Musgrave. Companion to Brahms: Biographical, Documentary, and Analytical Studies, Vol. 1, ed. Robert Pascall. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52-132606-3 (hbk). Reprinted in 2000, Symphony No. 4 in E Minor, Op. 98: Authoritative Score, Background, Context, Criticism, Analysis, ed. Kenneth Hull, 306–325. Norton Critical Scores Series. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-96677-0 (pbk). Abridged from PhD diss., "Brahms the Allusive: Extra-Compositional Reference in the Instrumental Music of Johannes Brahms". Princeton: Princeton University. 1989.

- Geiringer, Karl and Irene Geiringer. 1982. Brahms: His Life and Work. Third edition, revised and enlarged with appendix ("Brahms as a Reader and Collector"). New York: Da Capo Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-306-80223-2 (pbk).

- Hofmann, Kurt. "Brahms the Hamburg musician 1833–1862". In Musgrave (1999), pp. 3–30.

- Hofmann, Kurt; Hofmann, Renate (2010). Brahms Museum Hamburg: Exhibition Guide. Translated by Trefor Smith. Hamburg: Johannes-Brahms-Gesellschaft.

- Kross, Siegfried. 1983. "Brahms the symphonist". Brahms: Biographical, Documentary, and Analytical Studies, ed. Robert Pascall, 125–146. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Digitally reprinted 2008. ISBN 978-0-521-24522-7 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-521-08836-7 (pbk).

- Lamb, Andrew (October 1975). "Brahms and Johann Strauss". The Musical Times. 116 (1592): 869–871. doi:10.2307/959201. JSTOR 959201.

- MacDonald, Malcolm (2001) [1990]. Brahms. Master Musicians (2nd ed.). Oxford: Dent. ISBN 978-0-19-816484-5.)

- Massey, Drew. 2021. "The Dilemmas of Musical Surrealism". In Thomas Adès in Five Essays, 93–139. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199374960.003.0005. ISBN 978-0-19-754039-8 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-19-937496-0 (hbk).

- Maurer Zenck, Claudia. 1999. "Challenges and Opportunities of Acculturation: Schoenberg, Krenek, and Stravinsky in Exile". In Driven into Paradise: The Musical Migration from Nazi Germany to the United States, eds. Reinhold Brinkmann and Christoph Wolff, 172–193. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21413-2 (hbk).

- Musgrave, Michael (1985). The Music of Brahms. Oxford: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-7100-9776-7.

- Musgrave, Michael, ed. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Brahms. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.. Digitally reprinted 2006. ISBN 978-0-521-48129-8 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-521-48581-4 (pbk).

- Musgrave, Michael (1999a). Preface. In Musgrave (1999), pp. xix–xxii.

- Musgrave, Michael (1999b). "Years of transition: Brahms and Vienna 1862–1875". In Musgrave (1999), pp. 31–50.

- Musgrave, Michael (2000). A Brahms Reader. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06804-7.

- Parmer, Dillon. 1995. "Brahms, Song Quotation, and Secret Programs". 19th-century Music. 19(2):161–190. doi:10.2307/746660.

- Pascall, Robert (n.d.). Brahms: Symphony No. 1/Tragic Overture/Academic Festival Overture (CD liner). Naxos Records. 8.557428. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - Petersen, Peter (1983). Brahms: Works for Chorus and Orchestra (CD liner). Polydor Records. 435 066-2.

- Schumann, Robert (1988). Schumann on Music. tr. and ed. Henry Pleasants. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-25748-8.

- Swafford, Jan (1999). Johannes Brahms: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-72589-4.

- Swafford, Jan (2001). "Did the Young Brahms Play Piano in Waterfront Bars?". 19th-Century Music. 24 (3): 268–275. doi:10.1525/ncm.2001.24.3.268. ISSN 0148-2076. JSTOR 10.1525/ncm.2001.24.3.268.

- Swafford, Jan (2012). Johannes Brahms: A Biography. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 978-0-307-80989-6.

- Taruskin, Richard (2010). Music in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538483-3.

- Venn, Edward. 2015. "Thomas Adès and the Spectres of Brahms". Journal of the Royal Musical Association. 140(1):163–212. doi:10.1080/02690403.2015.1008867.

Further reading

- Adler, Guido. 1933. "Weiheblatt zum 100. Geburtstag des Johannes Brahms: Wirken, Wesen, und Stellung. Mitgliedes unserer leitenden Kommission." Studien zur Musikwissenschaft (Wien). 20:6–27. Reprinted in 1933, "Johannes Brahms: Wirken, Wesen, und Stellung. Gedenkblatt zum 100. Geburtstag gewidmet ihrem Mitgliede von der leitenden Kommission der Denkmäler der Tonkunst in Österreich". Wien: Universal Edition. Trans. in 1933 by W. Oliver Strunk, "Johannes Brahms: His Achievement, His Personality, and His Position". The Musical Quarterly. 19(2):113–142. doi:10.1093/mq/XIX.2.113.

- Beaudoin, Richard. 2024. Sounds as They Are: The Unwritten Music in Classical Recordings. Oxford Studies in Music Theory, gen. ed. Steven Rings. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-765930-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-19-765928-1 (hbk). doi:10.1093/ oso/ 9780197659281.001.0001.

- Brown, A. Peter. 2003. The Second Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Brahms, Bruckner, Dvořák, Mahler, and Selected Contemporaries. Vol. 4, The Symphonic Repertoire. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-33488-6 (hbk).

- Brown, Clive. 2000. Classical & Romantic Performing Practice 1750–1900, fwd. Roger Norrington. Reprinted 2002, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816165-3 (hbk).

- Burkholder, J. Peter. 1984. "Brahms and Twentieth-Century Classical Music". 19th-century Music. 8(1):75–83. doi:10.2307/746255.

- Dingle, Christopher, ed. et al. 2019. The Cambridge History of Music Criticism. The Cambridge History of Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03789-2 (hbk). doi:10.1017/9781139795425.

- Fink, Robert. 1993. "Desire, Repression & Brahms's First Symphony". repercussions. 2(1):75–103.

- Floros, Constantin. 2012. Humanism, Love and Music, trans. Ernest Bernhardt-Kabisch from the original German. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-653-04219-1 (ebk). ISBN 978-3-631-63044-0 (hbk).

- Frisch, Walter. 1993. The Early Works of Arnold Schoenberg, 1893–1908. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07819-2 (hbk).

- Frisch, Walter. 2005. German Modernism: Music and the Arts. California Studies in 20th-Century Music, gen ed. Richard Taruskin. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24301-9 (hbk).

- Fuller Maitland, John Alexander. 1911. Brahms. The New Library of Music Series, gen ed. Ernest Newman. New York: John Lane Co.

- Grimes, Nicole. 2019. The Poetics of Loss in Nineteenth-Century German Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-47449-8 (hbk). doi:10.1017/9781108589758.

- Grimes, Nicole. 2012. "The Schoenberg/Brahms Critical Tradition Reconsidered". Music Analysis 31(2):127–175. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2249.2012.00342.x.

- Grimes, Nicole, Siobhán Donovan, and Wolfgang Marx, eds. et al. 2013. Rethinking Hanslick: Music, Formalism, and Expression. Vol. 97, Eastman Studies in Music Series, senior ed. Ralph P. Locke. Rochester: University of Rochester. ISBN 978-1-58046-432-1 (hbk).

- Hadow, William Henry. 1895. Frederick Chopin, Antonin Dvořák, and Johannes Brahms. Vol. 2, Studies in Modern Music. London: Seeley and Co. Reprinted, London: Kennikat Press, 1970.

- Hancock, Virginia. 1983. Brahms's choral compositions and his library of early music. Studies in Musicology Series (76), gen ed. George Buelow. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. Reprint of DMA thesis. Portland: University of Oregon. 1977.

- Hart, Brian, A. Peter Brown, eds. et al. 2023. The Symphony in the Americas. Vol. 5, The Symphonic Repertoire, founding ed. A. Peter Brown. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-06754-8 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-253-06753-1 (hbk).

- Hefling, Stephen E., ed. et al. 2004. Nineteenth-Century Chamber Music. Routledge Studies in Musical Genres, gen. ed. R. Larry Todd. Reprinted (New York: Schirmer Books, 1998). New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96650-4 (pbk).

- Krummacher, Friedhelm. 1994. "Reception and Analysis: On the Brahms Quartets, Op. 51, Nos. 1 and 2". 19th-century Music. 18(1):24–45. doi:10.2307/746600.

- Loges, Natasha and Katy Hamilton, eds. et al. 2019. Brahms in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-16341-6 (hbk). doi:10.1017/9781316681374.

- Musgrave, Michael. 1979. "Schoenberg and Brahms: A study of Schoenberg's response to Brahms's music as revealed in his didactic writings and selected early compositions". PhD thesis. London: King's College.

- Notley, Margaret. 1993. "Brahms as Liberal: Genre, Style, and Politics in Late Nineteenth-Century Vienna". 19th-century Music. 17(2):107–123. doi:10.2307/746329.

- Pederson, Sana. 1993. "On the Task of the Music Historian: The Myth of the Symphony after Beethoven". repercussions. 2(2):5–30.

- Rink, John. 2024. Music in Profile: Twelve Performance Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-756542-1 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-19-756539-1 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-19-756540-7 (pbk). doi:10.1093/oso/9780197565391.001.0001.

- Scherzinger, Martin with Neville Hoad. 1997. "Anton Webern and the Concept of Symmetrical Inversion: A Reconsideration on the Terrain of Gender". repercussions. 6(2):63–147.

- Schoenberg, Arnold. 1990. Structural Functions of Harmony, ed. Leonard Stein. Reprint from revised edition with corrections, 1969. First published 1954. London and Boston: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-13000-9 (pbk).

- Schubert, Giselher. 1994. "Themes and Double Themes: The Problem of the Symphonic in Brahms". 19th-century Music. 18(1):10–23. doi:10.2307/746599.

- Taruskin, Richard. 1995. Text and Act: Essays on Music and Performance. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509437-4 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-19-509458-9 (pbk).

- Taruskin, Richard. 2009. Music in the Early Twentieth Century. The Oxford History of Western Music, Vol. 4. Rev. edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538484-0 (pbk).

- Taruskin, Richard. 2020. Cursed Questions: On Music and Its Social Practices. Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-97545-3 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-520-34428-0 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-520-34429-7 (pbk).

- Todd, R. Larry, ed. et al. 2004. Nineteenth-Century Piano Music. Routledge Studies in Musical Genres, gen. ed. R. Larry Todd. Second edition. Reissued (New York: Schirmer Books, 1990). Digitally reprinted in 2006. New York and London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-19-765930-4 (ebk). ISBN 978-0-415-96890-4 (pbk).

- Vaillancourt, Michael. 1993. "Brahms's 'Sinfonie-Serenade' and the Politics of Genre". The Journal of Musicology. 26(3):379–403. doi:10.1525/jm.2009.26.3.379.

External links

- Brahms Institut, Lübeck Academy of Music

- Free scores by Brahms at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Free scores by Johannes Brahms in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores Mutopia Project

- Johannes Brahms at the Musopen project

- Texts and translations of vocal music by Brahms, LiederNet Archive

- "Discovering Brahms". BBC Radio 3.

- Listings of live performances, Bachtrack

- Johannes Brahms WebSource

- Digitised recordings at the British Library Sounds