Boelcke-Kaserne concentration camp

| Boelcke-Kaserne | |

|---|---|

| Subcamp of Mittelbau-Dora | |

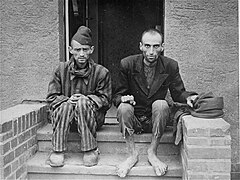

Two survivors among the dead | |

| Other names | Nordhausen |

| Known for | Graphic photographs of Nazi brutality |

| Location | Nordhausen, Germany |

| Operated by | SS-Totenkopfverbände |

| Commandant | Heinrich Josten |

| Original use | Luftwaffe barracks |

| Operational | 8 January – 11 April 1945 |

| Inmates | Sick and dying prisoners, largely Jews |

| Number of inmates | 5,700 |

| Killed | 3,000[a] |

| Liberated by | US Army |

Boelcke-Kaserne concentration camp (transl. Boelcke Barracks; also Nordhausen) was a subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp complex where prisoners were left to die after they became unable to work. It was located inside a former Luftwaffe barracks complex in Nordhausen, Thuringia, Germany, adjacent to several pre-existing forced labor camps. During its three-month existence, about 6,000 prisoners passed through the camp and almost 3,000 died there under "indescribable" conditions. More than a thousand prisoners were killed during the bombing of Nordhausen by the Royal Air Force on 3–4 April 1945. Their corpses were found by the US Army units that liberated the camp on 11 April. Photographs and newsreel footage of the camp were reported internationally and made Nordhausen notorious in many parts of the world.

History

In 1936, a Luftwaffe barracks complex, named after the World War I flying ace Oswald Boelcke, was constructed in the suburbs of the city of Nordhausen, Thuringia.[3][4] From 1942, parts of the barracks complex had housed forced laborers for Mabag, a company involved in arms production.[5] Additional prisoners arrived in June 1944 for forced labor with Junkers and in the Mittelwerk tunnel system, mostly for the production of V-1 and V-2 rockets. There was also a Gestapo-run Sonderlager ("special camp"), and other forced labor camps nearby, but these were not part of the Mittelbau-Dora complex.[3][4]

On 8 January 1945, the SS-Totenkopfverbände, which ran the concentration camp system, took over two two-storey garages of the Luftwaffe barracks to use as housing for 6,000 prisoners who were forced to work in the V-2 rocket production in nearby underground factories.[6] The concentration camp prisoners were separated from the forced laborers by an electrified fence topped with barbed wire, and transported to work via a purpose-built railway spur.[5][7] The camp commander was SS-Obersturmführer Heinrich Josten, who had previously worked at Auschwitz, and the deputy commander was SS-Hauptscharführer Josef Kestel, previously a functionary at the Dora camp.[4][7]

Beginning in late January, many Jewish prisoners in poor physical condition arrived at the Mittelbau-Dora complex from Auschwitz and Gross-Rosen.[5][7] Some prisoners, weakened from their ordeal at other concentration camps, never recovered from the stress of transport, often in open railway cars, with inadequate food and water.[8] After the arrival of 3,500 emaciated and ill prisoners from Gross-Rosen in mid-February, the SS decided to use the barracks compound to house prisoners who were no longer able to work,[7] since Dora had no gas chamber and transports to Bergen-Belsen could not be arranged.[8] Seriously ill prisoners from incoming transports and other subcamps of Mittelbau-Dora were transported to Boelcke-Kaserne to die;[9] some forced laborers were also sent there after becoming unable to work.[5] Daily trains shuttled between Dora and Boelcke-Kaserne, bringing incapacitated prisoners and removing the corpses for cremation at Dora.[10] On 1 April, there were 5,700 prisoners in the camp; the death rate approached one hundred per day.[4][7]

On 2 April, 3,000 prisoners were transported to the Mittelbau main camp and to Ellrich, a subcamp of Mittelbau. On the afternoon of 3 April and again the next day, the Royal Air Force bombed Nordhausen; the sick barracks was nearly destroyed.[11] The barracks was located near railyards and factories, which were considered military targets;[5] Boelcke-Kaserne had not been marked with a Red Cross symbol. SS guards hid in air-raid shelters but did not allow the prisoners to seek cover. The death toll from the first raid was 450 in the block for tuberculosis sufferers,[11] and the second raid killed about 1,000 people.[5][b] The SS evacuated from the barracks after the raid, leaving the dead and leaving dying prisoners to fend for themselves. Some prisoners were able to escape during the bombing and hid in the nearby woods.[12][13]

Conditions

Housing conditions were particularly bad, because there were no bunks; prisoners had to sleep in a thin layer of straw. One of the garages held four blocks of prisoners still able to work, for whom conditions were slightly better, but for all prisoners, rations were grossly insufficient to sustain life.[7][5] According to the Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, "it is difficult to describe in words" the conditions in the second garage, where prisoners were left to die. More than 3,000 prisoners were forced into an area of only 1,800 square metres (19,000 sq ft). Although there were toilets, they did not work for lack of water, and many prisoners were unable to move. Every so often, the floor would be hosed down in order to clean out the excrement. SS guards barely entered the camp, instead allowing the prisoners to die from neglect. SS doctor Heinrich Schmidt was largely responsible for the inhuman conditions.[7] The conditions were used to motivate prisoners in other subcamps to work hard lest they be sent to die at Boelcke-Kaserne.[5] Prisoners called it a "living crematorium" (German: lebendes Krematorium).[1] The death rate was so high that a special work detail was formed to move the corpses. Prisoners assigned to this duty could draw the rations of the dead.[14]

Boelcke-Kaserne housed the largest percentage of Jews in the Mittelbau-Dora complex, except for one labor subcamp for Jewish women. Forty percent of the prisoners were Polish, of whom most were thought to be Jews. The other main national groups were Russians, Frenchmen, and Hungarian Jews.[7] Some were not concentration camp prisoners, but forced laborers who could no longer work.[5] Most of the prisoner functionaries were German "green triangle" prisoners (convicted criminals) whose beatings and cruelty made the situation even worse.[7][14]

- Boelcke-Kaserne after liberation

- Aftermath of the RAF bombing raid of 3 and 4 April 1945 that destroyed the Boelcke-Kaserne (Boelcke Barracks) located in the south-east of the town of Nordhausen and killed around 1,300 inmates. The barracks was a subcamp of the Mittelbau-Dora Nazi concentration camp. Used as an overflow camp for sick and dying inmates from January 1945, numbers rose from a few hundred to over 6000, and the conditions saw up to 100 inmates die every day.

- German civilians bury victims under US Army supervision

- Two emaciated survivors

- Corpses after liberation

Liberation and aftermath

On 11 April, advance parties of the US 3rd Armored Division entered Nordhausen with little opposition.[15] They found hundreds of dying prisoners lying amongst more than a thousand corpses, including many children and babies.[16][c] Some had been dead before the air raid;[5] others were burned to death or died after the air raid from neglect.[16] The American soldiers were outraged; one wrote, "No written word can properly convey the atmosphere of such a charnel house, the unbearable stench of decomposing bodies, the sight of live human beings... lying cheek by jowl with the ten-day dead..."[15] A 15 April report describes the camp as "the most horrifying example of Nazi terrorism imaginable".[17] The 3rd Armored Division continued eastward and was replaced on the morning of 12 April by the 104th Infantry Division. According to some accounts, soldiers of the 104th Infantry Division killed German civilians in Nordhausen who denied knowledge of the atrocities, believing that they were partially responsible.[17]

The prisoners in the worst critical condition were taken to the 51st Field Hospital. Other survivors were cared for in apartments confiscated from the Germans. Despite these efforts, at least 59 former prisoners died of starvation and exhaustion.[15][18] By 14:30 on 13 April, all survivors had been removed from the camp. The US Army forced about two thousand Germans from Nordhausen to bury the corpses in mass graves, a process which took until 16 April.[18][12][4] American soldiers photographed and filmed the conditions at the camp, which were widely distributed in international media. Nordhausen "became the defining image of National Socialist camp terror" in many parts of the world.[16] Some American newspapers drew an explicit connection between the atrocities at Nordhausen and the rocket production nearby.[19]

Josten and Kestel were tried at the Auschwitz Trial in Kraków and the Buchenwald Trial at Dachau respectively; both were convicted and executed for crimes committed at other camps. Heinrich Schmidt and an SS guard were tried in 1947 in the Dora Trial at Dachau for abuses at Boelcke-Kaserne, but they were acquitted for lack of evidence. Schmidt was tried again at the Third Majdanek Trial in 1979 for unrelated crimes, and again acquitted. No one else was tried for crimes committed at the subcamp.[4][12]

According to Michael J. Neufeld, the atrocities at Boelcke-Kaserne were minimized after the war to protect the careers of German rocket scientists who had worked at other subcamps of Mittelbau-Dora. Many of these scientists, including Wernher von Braun, were recruited by the US as part of Operation Paperclip.[19] Since 1974, there has been a memorial at the site.[20]

References

Notes

- ^ SS files list 1,662 deaths between 8 January and 2 April 1945, but this is believed to be incomplete, and does not include those who died in the bombing or around the time of liberation. The figure of 3,000 does not include the 2,250 sick and dying prisoners who were sent on an "annihilation transport" to Bergen-Belsen around 8 March; almost all perished.[1][2]

- ^ According to German historian Jens-Christian Wagner, the total number killed in both air raids was 1,300, including forced laborers in the adjacent camp.[4]

- ^ Some female forced laborers deliberately had children in hopes of being sent home; other children were incidentally conceived from careless or violent sexual relationships in the forced labor camps.[5]

Citations

- ^ a b Wagner 2001, p. 495.

- ^ "Mittelbau (Dora) Main Camp". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- ^ a b USHMM 2009, p. 990.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wagner 2005, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Schafft & Zeidler 2011, p. 45.

- ^ USHMM 2009, pp. 974, 991.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i USHMM 2009, p. 991.

- ^ a b Sellier 2003, p. 280.

- ^ USHMM 2009, pp. 969, 1937.

- ^ Sellier 2003, p. 282.

- ^ a b USHMM 2009, pp. 991–2.

- ^ a b c USHMM 2009, p. 992.

- ^ Wagner 2001, p. 284.

- ^ a b Sellier 2003, p. 283.

- ^ a b c Sellier 2003, p. 313.

- ^ a b c USHMM 2009, pp. 970, 990.

- ^ a b Mauriello 2017, p. 35.

- ^ a b Mauriello 2017, p. 36.

- ^ a b Neufeld 2009, p. 71.

- ^ "Boelcke-Kaserne". nordhausen-im-ns.de (in German). Retrieved 26 August 2018.

Bibliography

- Mauriello, Christopher E. (2017). Forced Confrontation: The Politics of Dead Bodies in Germany at the End of World War II. Lanham: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-4985-4806-9.

- Neufeld, Michael J. (2009). "Creating a Memory for the German Rocket Program for the Cold War". Remembering the space age: Proceedings of the 50th Anniversary Conference. Government Printing Office. ISBN 978-1-4700-3180-0.

- Schafft, Gretchen E.; Zeidler, Gerhard (2011). Commemorating Hell: The Public Memory of Mittelbau-Dora. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09305-0.

- Sellier, Andre (2003). A History of the Dora Camp: The Untold Story of the Nazi Slave Labor Camp That Secretly Manufactured V-2 Rockets. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 978-1-4617-3949-4.

- USHMM (2009). Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945. Vol. 1. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-0-253-35328-3.

- Wagner, Jens-Christian [in German] (2005). "Nordhausen (Boelcke-Kaserne)". In Benz, Wolfgang; Distel, Barbara; Königseder, Angelika (eds.). Der Ort des Terrors (in German). Vol. 7. Munich: C.H.Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-52967-2.

- Wagner, Jens-Christian (2001). Produktion des Todes (in German). Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89244-439-8.