Bobby Riggs

Riggs c. 1947 | |

| Full name | Robert Larimore Riggs |

|---|---|

| Country (sports) | |

| Born | February 25, 1918 Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Died | October 25, 1995 (aged 77) Encinitas, California, U.S.[1] |

| Height | 5 ft 7 in (170 cm) |

| Turned pro | 1941 (amateur tour 1933) |

| Retired | 1962 |

| Plays | Right-handed (one-handed backhand) |

| Int. Tennis HoF | 1967 (member page) |

| Singles | |

| Career record | 838–326 (71.9%)[2] |

| Career titles | 103[2] |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1939, Gordon Lowe)[3] |

| Grand Slam singles results | |

| French Open | F (1939) |

| Wimbledon | W (1939) |

| US Open | W (1939, 1941) |

| Professional majors | |

| US Pro | W (1946, 1947, 1949) |

| Wembley Pro | F (1949) |

| Doubles | |

| Career record | not listed |

| Career titles | not listed |

| Highest ranking | No. 1 (1942, Ray Bowers) |

| Grand Slam doubles results | |

| Wimbledon | W (1939) |

| Grand Slam mixed doubles results | |

| Wimbledon | W (1939) |

| US Open | W (1940) |

Robert Larimore Riggs (February 25, 1918 – October 25, 1995)[4] was an American tennis champion who was the world No. 1 amateur in 1939 and world No. 1 professional in 1946 and 1947.[3] He played his first professional tennis match on December 26, 1941.

As a 21-year-old amateur in 1939, Riggs won the singles title at Wimbledon,[5] the U.S. National Championships (now U.S. Open), and was runner-up at the French Championships. He was U.S. champion again in 1941, after a runner-up finish in the previous year. At the 1939 Wimbledon Championships he also won the Men's Doubles and the Mixed Doubles.

After retirement from his pro career, Riggs became well known as a hustler and gambler. He organized numerous exhibition challenges, inviting active and retired tennis pros to participate. In 1973, aged 55, he held two such events, first against the No. 1–ranked woman player Margaret Smith Court, which he won, and another against the then-current women's champion Billie Jean King,[6] which he lost.[7][8] The latter, the primetime "Battle of the Sexes" match, remains one of the most famous tennis events of all time, with a $100,000 ($686,000 today) winner-takes-all prize.

Tennis career

Junior career

Born and raised in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, Riggs was one of six children of Agnes (Jones) and Gideon Wright Riggs, a minister.[9] He was an excellent table tennis player as a boy and when he began playing tennis at age twelve,[1] he was quickly befriended and then coached by Esther Bartosh, who was the third-ranking woman player in Los Angeles. Depending entirely on speed and ball control, he soon began to win boys (through 15 years old) and then juniors (through 18 years old) tournaments. Although it is sometimes said that Riggs was one of the great tennis players nurtured at the Los Angeles Tennis Club by Perry T. Jones and the Southern California Tennis Association, Riggs writes in his autobiography that for many years Jones considered Riggs to be too small and not powerful enough to be a top-flight player. (Jack Kramer, however, said in his own autobiography that Jones turned against Riggs "for being a kid hustler".)[10]: 21

After initially helping Riggs, Jones then refused to sponsor him at the important Eastern tournaments. With the help of Bartosh and others, Riggs played in various National Tournaments and by the time he was 16 was the fifth-ranked junior player in the United States. The next year he won his first National Championship, winning the National Juniors by beating Joe Hunt in the finals. That same year, 1935, he met Hunt in 17 final-round matches and won all 17 of them. He went undefeated for four years of play at Franklin High School (in the Highland Park neighborhood of Los Angeles) and was the first person to win California's state high school singles trophy three times.[11]

Amateur career

- 1934

In August aged 16, Riggs won the Ohio Valley tournament beating Archie McCallum in the final. The final was "a victory of youthful determination over veteran court generalship."[12]

- 1935

In July Riggs won the Utah championships in Salt Lake City beating Joe Hunt in the final. "The largest crowd in Salt Lake tennis history watched the final day’s encounters which climaxed the greatest tournament ever staged in this state".[13]

- 1936

At 18 in 1936, Riggs was still a junior but won the Southern California Men's Title, Los Angeles Ambassador hotel event and Los Angeles metropolitan championships and then went East to play on the grass-court circuit in spite of Jones's opposition. Riggs won the U.S. Men's Clay Court Championships in Chicago, beating Frank Parker in the finals with drop shots and lobs. He also won Missouri Valley, Nassau Bowl, Cincinnati, the Eastern Clay Court Championships at Jackson Heights, Newport Casino, Pennsylvania Clay Court Championships and Dade County tournaments.

Riggs beat Parker in the final of the Newport tournament, which was one of the lead-up events before the U.S. Championships. "Riggs, who has a well-rounded game and a rare knack of keeping the ball in play, owed his victory to his accurate backhand returns to the far corners. He pumped those shots at Parker whenever he tried to storm the net. After going two sets down Parker rallied in spectacular fashion and reached his peak early in the fourth set when he swept the first four games. He then dropped the next three but managed to crack through Riggs again in the tenth game to win the set at 6-4 and square the match. But Parker was doomed as soon as he threw away the opening game in the final set. This break appeared to unnerve him and Riggs raced through four straight games before Parker was able to win the fifth on his own service, his only triumph in the decisive series of games".[14] Although still a junior, Riggs ended the year ranked fourth in the United States Men's Rankings.

- 1937

Kramer, who was three years younger than Riggs, writes "I played Riggs a lot then at the Los Angeles Tennis Club. He liked me personally too, but he'd never give me a break. For as long as he possibly could, he would beat me at love ... Bobby was always looking down the road. 'I want you to know who's the boss, for the rest of your life, Kid,' he told me. Bobby Riggs was always candid."[10]: 31 In 1937, Riggs won 14 tournaments: Hillcrest invitational in Los Angeles, Huntington invitational in Pasadena, Southern California championships, New England championships, Nashville championships, U.S. Clay court championships, Cincinnati, Fox River Valley championships in Neenah, Colorado championships in Denver, Seabright, Southampton, Eastern grass court championships, Atlanta, and New Orleans.

- 1938

As a 20-year-old amateur, Riggs was part of the American Davis Cup winning team in 1938. He also won 14 tournaments. The events were: Miami Beach, Dixie championships in Tampa, Miami surf club, Palm Beach, Atlanta, Missouri valley, U.S. Clay court championships, Cincinnati, Fox River valley championships in Neenah, Illinois championships in Chicago, Longwood in Boston, Seabright, Eastern grass court championships and Southampton. Riggs's victory in the U.S. Clay court championships was his third in succession. He beat Gardnar Mulloy in the final in five sets. "Mulloy passed Riggs consistently in the second and third sets of their five-set match, but Bobby came back the fresher in the last two, going to the net again and again to kill Mulloy's drives".[15]

- 1939

In 1939, Riggs made it to the finals of the French Championships (where he lost to Don McNeill) but then won the Wimbledon Championships triple, capturing the singles,[5] the doubles with Cooke, and mixed doubles with Alice Marble, who also won all three titles.[16] His singles final win over Cooke lasted five sets. "In the final set the first two games fell to Riggs the next two to Cooke now calling on his attacking reserves. In the neatest and most unconcerned way possible Riggs poached the next four games against an adversary obviously footsore. Riggs won the eighth and last game easily and a match which while rather lacking pep, had been entertaining enough in its clever way."[17] Riggs won $100,000 betting on the triple win, then went on to win the U.S. Championships (beating Welby van Horn in the final), earning the world No. 1 amateur ranking for 1939. He also won events at Western indoors in Chicago, Bermuda championships, Chattanooga, Asheville, Hot Springs, Southampton, Eastern grass court championships, Pacific Coast championships and Chicago indoors. Riggs was ranked World No. 1 amateur by Pierre Gillou,[18] Ned Potter,[19] F. Gordon Lowe,[20] The Times,[21] G.H. McElhone[22] and Alfred Chave.[23]

- 1940

Riggs teamed up with Alice Marble, his Wimbledon co-champion, to win the 1940 U.S. Championships mixed doubles title. He lost in the 1940 U.S. Championships final to McNeill. Riggs won 14 tournaments in 1940 at Palm Beach, Pensacola, Miami, Augusta, U.S. Indoors, River Oaks in Houston, Cincinnati, Fox River Valley in Neenah, Western championships in Indianapolis, Seabright, Eastern grass court championships, Pacific southwest, Pacific Coast and New Orleans. At Seabright, Riggs had to come from two sets down to beat Frank Kovacs in the final. "Four times in the match Kovacs was one point removed from victory only to have the rampaging Riggs pull the game out. When the marathon ended with darkness settling over the court, a sell-out gallery stood and cheered while Bobby received the famous Seabright bowl."[24]

- 1941

In 1941, he won his second U.S. Championships singles title (beating Frank Kovacs in the final), following which he turned professional. He also won events at Palm Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Jacksonville, Pensacola, Chattanooga, Kansas City, Louisville, Western championships in Indianapolis, Seabright and Southampton.

Professional career

- 1942-1945

In the 1942 pro tour, Riggs finished second to Don Budge. He was also runner-up to Budge in the U.S. Pro. His career was quickly interrupted by military service during World War II as an enlisted Navy specialist.[25][26] While in Hawaii he was given a special mission by an admiral: "Improve the admiral's backhand", Riggs said.[27] During his military service, Riggs was a cornerstone member of the 1945 league champion 14th Naval District Navy Yard Tennis Team.

- 1945

After the war, Riggs returned to the pro circuit. He won the U.S. Pro hardcourt event in December in four sets over Budge. "Riggs, the former Franklin High School wonder, was clearly the sharper player and appeared to be getting better as the match wore on. It became a rout midway in the third, set when Budge, trailing 2-4, developed a cramp in his right forearm. He was granted a five-minute rest while his muscle was soothed but when play was resumed, Riggs continued his precise devastating base-line attack and broke the Oakland redhead's service for a 5-2 advantage. He then tacked down three straight placements and an ace to run out the set, 6-2. After a 10-minute intermission, during which time Budge's arm apparently failed to respond to treatments, they returned to the court for the formality of concluding the match. And a formality is all it was as the catlike Riggs drove home shot after shot or forced Budge into error. Riggs fairly sizzled as he racked up six straight games."[28] Riggs then won the Santa Barbara tournament over Perry.[29]

- 1946

Riggs won the US Pro title in 1946 over Budge. Riggs beat Budge in the World Pro challenge at Los Angeles in January. Riggs also won events at Palm Springs, Phoenix, Pasadena, Chattanooga, Boston, Oyster Harbors, Wentworth-by-the-Sea, Jefferson, Pittsburgh, Indianapolis, Oklahoma City and U.S. Pro hardcourt in Los Angeles.[30] There was a tournament series in 1946 organised by P. P. A.[31] The series awarded points to players based on their finish in each tournament. Riggs finished first in the tournament series with 278 points, then Budge (164 points), Kovacs (149 points), Van Horn (143 points), Earn (94 points), Sabin (74 points), Faunce (68 points), Jossi (60 points), Perry (50 points). Riggs was ranked World No. 1 pro by P. P. A.[32] This would be the first reported major professional tennis championship tournament series, and not repeated until 1959, 1960, and then 1964–68.

In the 1946 head-to-head tour against Budge, Riggs won 24 matches and lost 22, plus 1 match tied at Birmingham, Alabama establishing himself as the best player in the world.[33] Budge had sustained an injury to his right shoulder in a military training exercise during the war and had never fully recovered his earlier flexibility. In 1946, according to Kramer, "Bobby played to Budge's shoulder, lobbed him to death, won the first twelve matches, thirteen out of the first fourteen, and then hung on to beat Budge, twenty-four matches to twenty-two."

- 1947

The promoter of the 1946 Riggs–Budge tour was Jack Harris. In mid-1947, he had already made a deal with Kramer that he would turn professional after the U.S. Championships, regardless of whether he was the winner. He also told Riggs and Budge that the winner of the Professional American Singles Championship, to be held at Forest Hills, would establish the World Champion who would defend his title against Kramer. Riggs was upset, believing that he had already established his right to be the defending world champion in a tour against Kramer. For the second year in a row, Riggs defeated Budge in the Forest Hills final, this time in a close five set match (Riggs also won the U.S. Pro indoors earlier in the year). Harris signed Kramer for 35 percent of the gross receipts and offered 20 percent to Riggs. He then changed his mind, as Riggs recounted in his autobiography, "saying he could get Ted Schroeder as one of the supporting pair, provided both Kramer and I would yield 2½ percent of our shares in order to build up the offer to Ted. We both agreed — and then Schroeder refused." Harris then signed Pancho Segura and Dinny Pails at $300 ($4,090 today) per week to play the opening match of the Riggs–Kramer tour. Riggs then went on to play Kramer for 17½ percent of the gross receipts.[34]: 16

- 1948

On December 26, 1947, Kramer and Riggs embarked on their long tour, beginning with an easy victory by Riggs in front of 15,000 people, who had made their way to Madison Square Garden in New York City in spite of a record snowstorm, that had brought the city to a standstill.[35][36] On January 16, 1948, Riggs led 8 matches to 6. At the end of 26 matches, Riggs and Kramer had each won 13. By that point, however, Kramer had stepped up his second serve to take advantage of the fast indoor courts they played on and was now able to keep Riggs from advancing to the net. Kramer had also begun the tour by playing a large part of each match from the baseline. Finally realizing that he could beat Riggs only from the net, he changed his style of game and began coming to the net on every point. Riggs was unable to handle Kramer's overwhelming power game. For the rest of the tour Kramer dominated Riggs mercilessly, winning 56 out of the last 63 matches. The final score was 69 victories for Kramer versus 20 for Riggs, the last time an amateur champion had beaten the reigning professional king on their first tour. In many of the last matches, it was assumed by observers that Riggs frequently gave up after falling behind and let Kramer run out the victory. Riggs says in his autobiography that Kramer had made "nearly a hundred thousand dollars ... on the American tour alone, while I took in nearly fifty thousand as my share."[34]: 25 [37]

- 1949

Riggs won the U.S. Pro in 1949 over Budge in four sets. "Gusts of wind made accuracy almost impossible and both veterans made a surprising number of errors. Budge who won the championship in 1940 and 1942 thrilled the crowd with his whistling forehand drives when he could reach his opponent’s placements. But in the end the younger Riggs wore down the red-haired Budge who is several years older... After dropping the third set Budge rallied to go ahead at 5-3 but that was his limit- Riggs began to force the play and took the next four games in a row finishing out the match with a service ace."[38] This was Riggs's final U.S. Pro title.

- 1950-1962

In 1951, more than 20 years before he faced Court and King, Riggs played a short series of matches against Pauline Betz. These matches were scheduled for the first match of the evening before Kramer faced Segura in the main World Series contest. The Riggs–Betz matches took place towards the end of the tour (after Betz's opponent Gussie Moran had left the tour). Riggs won the 1952 Gator Bowl Pro in Jacksonville.[39] In 1953, he won at Fort Lauderdale and the PLTA fall event at Long Island. In 1954, he won events at U.S. Pro clay court championships, Canada Pro[40] and Eastern States Pro. After that he played increasingly rarely, often making up the numbers at the U.S. Pro at Cleveland.

As a senior player in his sixties and seventies, Riggs won numerous national titles within various age groups.

Playing style

Small in stature, he lacked the overall power of his larger competitors such as Budge and Kramer, but made up for it with brains, ball control, and speed. A master court strategist and tactician, he worked his opponent out of position and scored points with the game's best drop shot and lob as well as punishing ground strokes that let him come to the net for put-away shots. Kramer, one of the very few players who were undeniably better than Riggs, writes that there is a major "misconception" about Riggs. "He didn't play some rinky-dink Harold Solomon style, pitty-pattying the ball around on dirt. He didn't have the big serve, but he made up for it with some sneaky first serves and as fine a second serve as I had seen at that time. When you talk about depth and accuracy both, Riggs's second serve ranks with the other three best that I ever saw: von Cramm's, Gonzales's, and Newcombe's." In his autobiography, Riggs wrote, "In the 1946 match with Budge [for the United States Pro Championship], I charged the net at every opportunity. Employing what I called my secret weapon, a hard first serve, I attacked constantly during my 6–3, 6–1, 6–1 victory."

"Riggs", said Kramer, "was a great champion. He beat Segura. He beat Budge when Don was just a little bit past his peak. On a long tour, as up and down as Vines was, I'm not so sure that Riggs wouldn't have played Elly very close. I'm sure he would have beaten Gonzales — Bobby was too quick, he had too much control for Pancho — and Laver and Rosewall and Hoad."

Kramer went on to say that Riggs "could keep the ball in play, and he could find ways to control the bigger, more powerful opponent. He could pin you back by hitting long, down the lines, and then he'd run you ragged with chips and drop shots. He was outstanding with a volley from either side, and he could lob as well as any man ... he could also lob on the run. He could disguise it, and he could hit winning overheads. They weren't powerful, but they were always on target."

Grand Slam

Singles : 3 titles, 2 runners-up

| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | 1939 | French Championships | Clay | 5–7, 0–6, 3–6 | |

| Win | 1939 | Wimbledon | Grass | 2–6, 8–6, 3–6, 6–3, 6–2 | |

| Win | 1939 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 6–4, 6–2, 6–4 | |

| Loss | 1940 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 6–4, 8–6, 3–6, 3–6, 5–7 | |

| Win | 1941 | U.S. Championships | Grass | 8–6, 7–5, 3–6, 4–6, 6–2 |

Pro Slam

Singles : 3 titles, 3 runners-up

| Result | Year | Championship | Surface | Opponent | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss | 1942 | US Pro | Grass | 2–6, 2–6, 2–6 | |

| Win | 1946 | US Pro | Grass | 6–3, 6–1, 6–1 | |

| Win | 1947 | US Pro | Grass | 3–6, 6–3, 10–8, 4–6, 6–3 | |

| Loss | 1948 | US Pro | Grass | 12–14, 2–6, 6–3, 3–6 | |

| Loss | 1949 | Wembley Pro | Indoor | 6–2, 4–6, 3–6, 4–6 | |

| Win | 1949 | US Pro | Grass | 9–7, 3–6, 6–3, 7–5 |

Performance timeline

Riggs joined the professional tennis circuit in 1941 and as a consequence was banned from competing in the amateur Grand Slams.

| W | F | SF | QF | #R | RR | Q# | DNQ | A | NH |

(A*) 1-set matches in preliminary rounds.

| 1936 | 1937 | 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | 1945 | 1946 | 1947 | 1948 | 1949 | 1950 | 1951 | 1952 | 1953 | 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | SR | W–L | Win % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grand Slam tournaments | 3 / 8 | 40–5 | 88.9 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Australian Open | A | A | A | A | A | not held | not eligible | 0 / 0 | 0–0 | – | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| French Open | A | A | A | F | not held | not eligible | 0 / 1 | 6–1 | 85.7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wimbledon | A | A | A | W | not held | not eligible | 1 / 1 | 7–0 | 100.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| US Open | 4R | SF | 4R | W | F | W | not eligible | 2 / 6 | 27–4 | 87.1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pro Slam tournaments | 3 / 18 | 36–16 | 69.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Pro | A | A | A | A | A | A | F | A | NH | A | W | W | F | W | SF | A | SF | A | SF | 1R | A | QF | A | QF | QF | QF | A | A* | A* | 3 / 13 | 29–11 | 72.5 |

| French Pro | A | A | A | A | not held | A | NH | A | A | A | A | A | 0 / 0 | 0–0 | – | |||||||||||||||||

| Wembley Pro | NH | A | NH | A | not held | F | SF | QF | QF | QF | NH | NH | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | 0 / 5 | 7–5 | 58.3 | ||||||||||

| Win–loss | 2–1 | 5–1 | 3–1 | 19–1 | 5–1 | 6–0 | 4–1 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 5–0 | 6–0 | 4–1 | 6–1 | 3–2 | 3–3 | 1–1 | 3–2 | 0–1 | 1–1 | 0–0 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–1 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 0–0 | 6 / 26 | 76–21 | 78.4 | ||

Hustling and gambling

Riggs was famous as a hustler and gambler,[41][42] when in his 1949 autobiography he wrote that he had made $105,000 ($2,300,000 today) in 1939 by betting in England, on himself, to win all three Wimbledon championships: the singles, doubles and mixed doubles. At the time, most betting was illegal in England. From an initial $500 bet on his chances of winning the singles competition, he eventually won the equivalent of $1.5 million in 2010 dollars. According to Riggs, World War II kept him from taking his winnings out of the country, so that by 1946 after the war had ended, he then had an even larger sum waiting for him in England as it had been increased by interest.

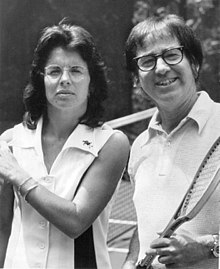

"Mother's Day Massacre" and "Battle of the Sexes"

In 1973, Riggs saw an opportunity to both make money and draw attention to the sport of tennis. He came out of retirement to challenge one of the world's greatest female players to a match, claiming that the female game was inferior and that a top female player could not beat him, even at the age of 55. After many failed attempts to lure Billie Jean King, he challenged Margaret Court, 30 years old and the top female player in the world, and they played on May 13, Mother's Day, in Ramona, California. Riggs used his drop shots and lobs to keep Court off balance;[43][44] his easy 6–2, 6–1 victory in less than an hour landed him on the cover of both Sports Illustrated and Time magazine.[44][45] The match was called the "Mother's Day Massacre".[46]

Riggs had originally challenged Billie Jean King, but she had declined, regarding the challenge as a fatuous gimmick. Following Court's loss to Riggs, King decided to accept his challenge,[47][48] and the two met in the Houston Astrodome on prime-time television on Thursday, September 20, in a match billed as The Battle of the Sexes.[6] The oddsmakers and writers favored Riggs;[49] he built an early lead, but King won in straight sets (6–4, 6–3, 6–3) for the $100,000 winner-take-all prize.[7][8]

The ESPN program Outside the Lines[50] made an allegation that Riggs took advantage of the overwhelming odds against King and threw the match to get his debts to the mob erased. The program featured a man who had been silent for 40 years, for reasons of self-protection, who claimed that he had worked at a country club, and there heard several members of the mafia talking about Riggs throwing the match in exchange for cancelling his gambling debt to the mob. The program also stated that Riggs's close friend and estate executor Lornie Kuhle vehemently denied Riggs was ever in debt to the mob or received a payoff from them.

In the 2017 film adaptation Battle of the Sexes, Riggs was played by Steve Carell, with Emma Stone as Billie Jean King.[51][52]

Personal life and death

Riggs was married twice, and had two sons from the first marriage, and three sons and a daughter from the second.[53] Before he was 21 Riggs dated a fellow tennis player Pauline Betz. Then, at the Illinois state tournament, he met Catherine "Kay" Fischer. They married in early December 1939 in Chicago, and divorced in the early 1950s.[54]

Riggs met his second wife, Priscilla Wheelan, on the courts of the LaGorce Country Club in Miami. Priscilla came from a wealthy family that owned the prominent America Photograph Corporation based in New York.[55] They married in September 1952,[54] divorced in 1971, and remarried in 1991.[56]

Riggs was diagnosed with prostate cancer in 1988. He and Lornie Kuhle founded the Bobby Riggs Tennis Club and Museum in Encinitas, California to increase awareness of the disease and house his memoirs/trophies. Riggs died on October 25, 1995, at his home in Leucadia, Encinitas, California, aged 77. He was survived by two sons from his first marriage, three children from his second marriage, two brothers and four grandchildren.[4][57]

In his final days, Riggs remained in friendly contact with Billie Jean King, and King phoned him often. She called him shortly before his death, offering to visit him, but he did not want her to see him in his condition. She phoned him one last time, the night before his death and, according to King in an HBO documentary about her, the last thing she told Riggs was "I love you."[58]

Honors

- Riggs was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1967.[1][59]

- Riggs Drive in Sandy, Utah was named for Riggs.[60] An adjoining street was named for Jack Kramer.

References

- ^ a b c Bobby Riggs. Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ a b "Bobby Riggs: Career match record". Tennis Base. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Official Encyclopedia of Tennis (First ed.). United States Lawn Tennis Association. 1972. p. 425.

- ^ a b Finn, Robin (October 26, 1995). "Irrepressible Riggs succumbs". The Dispatch. Lexington, NC. The New York Times. p. 1B.

- ^ a b "Riggs defeats Cooke to take Wimbledon title". Chicago Daily Tribune. July 8, 1939. p. 13.

- ^ a b Jares, Joe (September 10, 1973). "Riggs to riches – take two". si.com. p. 24.

- ^ a b "Billie Jean slam-bangs Riggs to defeat". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. September 21, 1973. p. 1, sec. 1.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, Curry (October 1, 1973). "There she is, Ms. America". Sports Illustrated. p. 30.

- ^ Garraty, John A.; Carnes, Mark C. (2005). American National Biography. Oxford University Press. pp. 476–. ISBN 978-0-19-522202-9.

- ^ a b Kramer, Jack; Deford, Frank (1979). The Game, My 40 Years in Tennis. Putnam. ISBN 0-399-12336-9.

- ^ Mcbride, Carrie. "Riggs, Robert Larimore ("Bobby")". encyclopedia.com. The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives. Retrieved August 27, 2019.

- ^ "The Cincinnati Enquirer". August 20, 1934 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Salt Lake Tribune". July 8, 1935 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Los Angeles Times". August 23, 1936 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Tampa Times". June 30, 1938 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Americans sweep 6 Wimbledon titles". Chicago Sunday Tribune. July 9, 1939. p. 1, sec. 2.

- ^ "The Evening Standard". July 7, 1939 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Les 10 meilleurs tennismen et tenniswomen du monde : Les Classements de M. P. Gillou" [The 10 best male and female tennis players in the world: the rankings of Mr. P. Gillou]. L'Auto (in French). September 22, 1939. pp. 1, 5.

- ^ "D'après E.C. Potter Junior : Le classement américain des " dix meilleurs " du tennis" [According to E.C. Potter Junior: The American ranking of the "ten best" in tennis]. L'Auto (in French). November 5, 1939. p. 3.

- ^ Almanacco illustrato del tennis 1989. Edizioni Panini. 1989. p. 693.

- ^ "Tennis Rankings: English Writer's Views". Gisborne Herald. Vol. 66, no. 20069. October 16, 1939. p. 4.

- ^ "HOME NEWS". The Sydney Morning Herald. No. 31, 737. New South Wales, Australia. September 19, 1939. p. 1. Retrieved November 28, 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Californians Head the World Tennis Rankings". Telegraph (Brisbane). Queensland, Australia. September 22, 1939. p. 13 (SECOND EDITION). Retrieved November 28, 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "The Tampa Bay Times". July 28, 1940 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Guam: U.S. makes little island into mighty base", Life, p. 74, July 2, 1945

- ^ Baron, S. (1997). They Also Served: Military Biographies of Uncommon Americans. MIE Publishing. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-877639-37-1.

- ^ Einstein, Charles. "When Football Went to War". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ "Los Angeles Times". December 10, 1945 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Lancaster New Era". December 31, 1945 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ The history of Professional tennis, Joe McCauley, 2003, p.189-192

- ^ McCauley, Joseph (2000). The History of Professional Tennis. The short run book company Ltd. pp. 42–43.

- ^ McCauley, Joseph (2000). The History of Professional Tennis. The short run book company Ltd. p. 43.

- ^ "American Lawn Tennis". July 15, 1946. p. 34.

- ^ a b Riggs, Bobby (1949). Tennis Is My Racket. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- ^ "Bobby Riggs Spoils Jack Kramer's Pro Debut, Winning Garden Match In 4 Sets Before Record Crowd". Times Daily. December 27, 1947. p. 8.

- ^ Anderson, Dave (January 21, 1963). "Tennis In A Blizzard". Sports Illustrated. Vol. 18, no. 3. pp. M3–M4.

- ^ Collins, Bud (2010). The Bud Collins History of Tennis (2nd ed.). New York: New Chapter Press. pp. 66, 67. ISBN 978-0942257700.

- ^ "The Knoxville Journal". June 27, 1949 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Honoloulu Star Bulletin". January 1, 1953 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Shreveport Journal". June 14, 1954 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Berkow, Ira (April 5, 1973). "Bobby Riggs: male chauvinist or hustler?". Argus-Press. Owosso, MI. NEA. p. 15.

- ^ Grimsley, Will (June 24, 1977). "Riggs still collects". Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). Associated Press. p. 19.

- ^ "Riggs "Courts" Margaret – then hustles a victory". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. May 14, 1973. p. 28.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, Curry (May 21, 1973). "Mother's Day Ms. match". Sports Illustrated. p. 34.

- ^ "Time Magazine Cover: Bobby Riggs – September 10, 1973". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007.

- ^ Roberts, Selena (August 21, 2005). "Tennis's Other 'Battle of the Sexes,' Before King-Riggs". The New York Times. Retrieved January 8, 2018.

- ^ "Riggs gets backing for tennis match with King". Florence Times. Alabama. Associated Press. July 12, 1973. p. 12.

- ^ "Evert claims Riggs refused her challenge". The Bulletin. Bend, OR. Associated Press. August 2, 1973. p. 11.

- ^ "Las Vegas favors Riggs". Ellensburg Daily Record. Washington. UPI. September 20, 1973. p. 8.

- ^ Van Natta, Don Jr. (August 25, 2013). "The Match Maker: Bobby Riggs, The Mafia and The Battle of the Sexes". ESPN.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (November 19, 2015). "Emma Stone Set to Star as Billie Jean King in Fox Searchlight's 'Battle of the Sexes' (EXCLUSIVE)". Archived from the original on March 29, 2016.

- ^ Battle of the Sexes (2017). IMDb

- ^ Sorensen, Steve (February 13, 1986). "Bobby Riggs, the legendary tennis hustler, has a hundred bucks that says he can beat you. Somehow". San Diego Reader.

- ^ a b Kirkpatrick, Curry (July 30, 1973). "All the World's a Stage". Sports Illustrated.

- ^ Tully, Shawn (September 20, 2017) Before the ‘Battle of the Sexes,’ I Was Bested by Bobby Riggs. finance.yahoo.com

- ^ Curry, Jack (1991) SIDELINES: BATTLE OF SEXES; Bobby Riggs in Love Rematch. The New York Times.

- ^ Oates, Bob (October 26, 1995) "Star-Turned Hustler Bobby Riggs Is Dead : Tennis: Wimbledon and U.S. Open champion who lost to Billie Jean King in the 'Battle of the Sexes' succumbs at 77 after long bout with cancer.", Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Interview with Billie Jean King, US Open telecast, August 28, 2006.

- ^ Finn, Robin (October 27, 1995) "Bobby Riggs, Brash Impresario Of Tennis World, Is Dead at 77", The New York Times.

- ^ (40.571914, −111.831420) Lat & Long Map. latlong.net

Sources

- Deford, Frank; Kramer, Jack (1979). The Game: My 40 Years in Tennis. New York: Putnam. ISBN 0-399-12336-9.

- McGann, George; Riggs, Bobby (1973). Court hustler. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott. ISBN 0-397-00893-7.

- Lecompte, Tom (2003). The Last Sure Thing: The Life & Times of Bobby Riggs. Black Squirrel Publishing. ISBN 0-9721213-0-7.

- LeCompte, Tom, "The 18-Hole Hustle", American Heritage Magazine, August/September 2005, volume 56, issue 4

- Roberts, Selena (2005). A Necessary Spectacle: Billie Jean King, Bobby Riggs, and the Tennis Match That Leveled the Game. New York: Crown. ISBN 1-4000-5146-0.

- Caroline Seebohm, Little Pancho, 2009

- Pancho Gonzales, Man with a Racket, 1959

- Gardnar Mulloy, As It Was, 2009