Black Jungle Conservation Reserve

| Black Jungle / Lambells Lagoon Conservation Reserve Black Jungle and Lambells Lagoon[1], Northern Territory | |

|---|---|

IUCN category VI (protected area with sustainable use of natural resources)[2] | |

| Coordinates | 12°30′08″S 131°11′39″E / 12.50224101°S 131.19429779°E[2] |

| Established | 25 March 1986[2] |

| Area | 49.51 km2 (19.1 sq mi)[2] |

| Managing authorities | Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory |

| See also | Protected areas of the Northern Territory |

The Black Jungle Conservation Reserve is a protected area in the Northern Territory of Australia near the territorial capital of Darwin. The rural area of Darwin and its development has a contrasting history to the more southern regions and their rural zones. The development of the rural area around Darwin occurred after 1950 as agricultural ventures were trialed. Prior to this the area was tropical savanna with pockets of monsoon rainforest and melaleuca swamps, unchanged for thousands of years, except by the traditional Aboriginal owners of the land who hunted and gathered and managed the landscape with fire. Black Jungle Conservation Reserve is a part of the Adelaide River Coastal Floodplain system which encompasses Black Jungle and Lambells Lagoon Conservation Reserves, Fogg Dam, Leaning Tree Lagoon Nature Park, Melacca Swamp and Djukbinj National Park. These Reserves encompass a range of wetland types and form part of the internationally significant Adelaide River floodplain.

These wetland habitats are important due to their high conservation value, supporting a variety of rare and threatened species; large waterbird populations, monsoon rainforests, breeding grounds for the estuarine or Saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), and the highest global recorded biomass of predator and prey species (water python and dusky rat). The wetland systems with its diverse landscapes include sites of ritual, mythological and spiritual significance to the traditional owners and have been a source of abundant traditional foods, medicine plants and other resources. Some of these areas also contain historical World War II sites.

Introduction

The Black Jungle and Lambells Lagoon Conservation Reserves (NT land portions 8 and 16.03) are joined by a narrow vegetated corridor approximately 3 km long through horticultural private land (Brockwell 2001). These reserves adjoin the Fogg Dam Reserve forming part of the Adelaide River Coastal Floodplain area (Brockwell 2001; Dept. LRM 2013). The Black Jungle section contains spring fed monsoon rainforest patches (Barrow et al. 1993; Dept. LRM 2013) which supports large numbers of wildlife, including populations of threatened species, and provides breeding habitats for wetland birds and saltwater crocodiles (NT Parks & Wildlife Comm.; Russell-Smith 1991; Salmon 2013). Springs and permanent water sources maintain pockets of rainforest and provide a dry season refuge for waterbirds (Russell-Smith 1991; Salmon 2013). The highest density breeding ground in the world for the magpie goose, Anseranus semipalmata, has been recorded near Black Jungle swamp; the conservation reserve being of particular importance in the wet season (Brockwell 2001; Parks & Wildlife Comm. NTG; Russell-Smith 1991).

- Magpie goose - Anseranus semipalmata

- estuarine crocodile –Crocodylus porosus

- Brolga - Grus Rubicundas

Location

The Black Jungle Conservation Reserve is about 62 kilometres (39 mi) southeast of Darwin, Northern Territory, located in the Hundred of Hutchison (ILUA). The reserve has restricted access to the public except via permit for scientific purposes, i.e. research, collection of crocodile eggs (Parks & Wildlife Commission; NTG).

Climate

This region of the Northern Territory is in the dry tropics being distinctly seasonal, having a long dry season from April to November and a shorter wet season from December to March. High rainfall of approximately 1380 mm is recorded annually the most rainfall occurring in January and February. Average daily temperatures are relatively stable throughout the year ranging from 31.2 °C in July and 35.6 °C in October. Night time temperatures average 15 °C in July and 23.8 °C in January and February. Humidity builds from September and remains reasonably high throughout the wet season (Bureau of Meteorology 2006).

Vegetation Structure

The area has been classified as open woodland savannah, with pockets of wet monsoon rainforest and melaleuca swamp and some areas dominated by grass and sedge communities (Russell-Smith 1991; Russell-Smith et al. 1991). The over-storey in the woodland is co-dominated by Eucalyptus miniata and E. tetrodonata species (Russell-Smith 1991; Russell-Smith et al. 1991). An important feature of wet monsoon rainforest is the availability of permanent moisture; in the form of permanent creeks and springs, dominated by evergreen trees and palms (Russell-Smith 1991; Russell-Smith et al. 1991). Generally these patches have a canopy height of up to 30 m, overlying a dense understorey of smaller ground ferns and sedges (Russell-Smith 1991; Russell-Smith et al. 1991).

Tenure and Land Use

Black Jungle/Lambells Lagoon Conservation Reserve is situated within the Adelaide River Coastal Floodplain and is a large, seasonally-inundated freshwater system that is traversed by a major and permanent tidal river, comprising a mix of tidal and seasonal wetland habitats (NTG – Sites of Conservation Significance). Almost half of the Adelaide River floodplain is pastoral leasehold land, belonging to Woolner and Koolpinyah Station (Russell-Smith 1991; NTG – Sites of Conservation Significance). Approximately 25% of the Adelaide River floodplain is managed for conservation, including Fogg Dam, Lambells Lagoon, Black Jungle, Malacca Swamp, Harrison Dam, Leaning Tree Lagoon and the Djukbinj National Park (Russell-Smith 1991; NTG – Sites of Conservation Significance).

History

Prior to European settlement, the region was managed traditionally by Aboriginals using fire-stick farming methods to ‘clear the land of vegetation’ (McGrath 1987). The Aborigines were known for their affinity with the land and a commitment to looking after the country (McGrath 1987). The name ‘Black Jungle’ first appeared on a plan of the ‘Umpity Doo Homestead’ block, Agricultural Lease No 28 in 1910.(De La Rue 2004; NTG 2013) ‘The Jungle’, as it was commonly referred to, was part of Koolpinyah Station granted to the Herbert brothers in 1907, by their father Government Resident Charles Edward Herbert; who was a senior member of parliament and judge in the Northern Territory between 1905 and 1910 (McGrath 1987; De La Rue 2004). Herbert had come to Darwin in 1884 and was keen to explore live cattle exports on the station, which at the time included Humpty Doo station (De La Rue 2004). In 1907 Koolpinyah Station was one of the largest and most significant cattle stations in the Northern Territory; spanning a vast area between Howards Springs to the west and the Adelaide River to the east (De La Rue 2004).

Koolpinyah Station was created when Herbert applied for leases over the area in the names of his sons (McGrath 1987; De La Rue 2004). The Koolpinyah Station lease was taken up by the Herbert brothers in 1908 for mixed farming (Territory Records 2007). Resident Herbert was instrumental in adapting land regulations for the industry believing that small mixed farming had great potential for the Territory (De La Rue 2004). The station lease was defined as a mixed farm of buffalo, goats, tropical fruit and cattle (McGrath 1987). The Herbert brothers established their homestead at a waterhole known by the local Aborigines as "Gulpinyah" (McGrath 1987). They hunted and gathered wild cattle on the station according to seasonal conditions and market demand (McGrath 1987). Aboriginal elders were welcomed by the Herberts who shared food supplies and money with them, when it was available and the elders were also allowed to camp on the property (De La Rue 2004; McGrath 1987). Botanist FAK Bleeser collected many palms in ‘The Jungle’ in the 1930s (McGrath 1987). In 1983, the Territory Government prepared the 1983 Darwin Rural Area Plan (Dept. LRM 2013; Wells 2003). While agriculture was a defined use, there was no specific agricultural or rural zone (Wells 2003). By 1990, the government had undertaken an investigation of lands suitable for horticulture with access to groundwater at Lambells Lagoon and Berry Springs (Salmon 2013; Dept. LRM 2013). Lambells Lagoon and lots in Acacia Hills were exchanged as land swaps for the Malacca Swamp and Black Jungle, which became conservation reserves, excised from the Koolpinyah pastoral station (Dept. LRM 2013; Wells 2003). These land swaps occurred prior to the Native Title Act 1993 which came into operation in January 1994 (ILUA).

Conservation

There are large areas of land set aside for the protection of conservation and biodiversity in the Top End of the Northern Territory; including Black Jungle, Malacca Swamp and the mangroves lining the Litchfield waterways (NTG – Sites of Conservation Significance; Russell-Smith 1991). There are also large parcels of land set aside to protect the water catchments (Salmon 2013). Salmon (2013) suggests that conservation of these areas did not emerge from a desire to protect the landscape; but from the need to protect the aquifers. Groundwater extraction in horticultural areas on the margin of the floodplain, impacts on freshwater springs and rainforest patches such as those around Black Jungle Swamp (Liddle et al. 2006). Conservation management of Black Jungle was established in 1986 and is controlled by the Northern Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission (NTG – Sites of Conservation Significance; Salmon 2013). Public access is strictly by permit only which is usually only granted for scientific research and crocodile egg harvesting (NTG – Sites of Conservation Significance; Liddle et al. 2006). It has been recorded that the reserve is sometimes illegally entered, usually by hunters in vehicles, or by ‘recreational’ vehicle users who damage fences and gates to gain entry to the reserve (Liddle et al. 2006).

Joint Management

The Register of Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ATNS 2011) describes the area as ‘the parcel of land near Black Jungle in the Hundred of Hutchison, Northern Territory of Australia, containing an area of 2006 hectares more or less being Section 8 more particularly delineated on Survey Plan S83/230A lodged with the Surveyor General, Darwin’ (ATNS 2011). Joint management between Northern Territory Government Parks and Wildlife Commission, and traditional Aboriginal owners has been operating in the Territory since 1981 to manage parks within the NT (ATNS 2011). The ILUA area falls within the Yilli Rreung Regional Council ATSIC area and the Litchfield Shire Council (ATNS 2011). In 2003, the Parks and Reserves Act was passed so that outstanding land and native title claims affecting twenty-seven parks and reserves could be settled (Parks & Reserves Act 2015). In 2005 the Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act was amended, setting out the principles and objectives for joint management for 27 'framework' parks (Parks & Reserves Act 2015).

Significant rare species

Black Jungle Reserve, Black Jungle Palm Site and the Black Jungle Orchid Site are included on the Register of the National Estate, for their natural values (Australian Heritage Council). Four conservation dependent species, including two which are listed in the IUCN Red List, are also found within the reserve and are listed below:

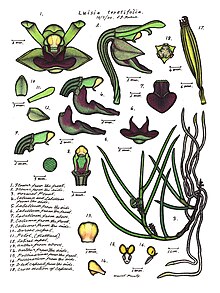

Luisia trsitis, Hook.f., orchid

This species is listed as Vulnerable by IUCN as less than 1000 mature individuals occupy an area of less than 20 km2 (Holmes et al. 2005). This epiphytic orchid species grows in straggly clumps and has wiry, erect or semi-pendulous slender stems up to 30 cm long. The roots are thick and cord-like, approx. 5 mm wide. The inflorescence raceme is up to 15 cm long with groups of 1 to 3 flowers of green or yellow-green, and a dark red to burgundy centre, approximately 1 cm wide. Flowering occurs from November to December, but has also been recorded in February (Holmes et al. 2005). L. tristis is found on the margins of monsoon vine forest and rainforest in areas of relatively bright light (suggesting reliance on breaks in the canopy) and is associated with other epiphytes (Holmes et al. 2005). This orchid has been recorded in Bankers Jungle and Black Creek, within the Black Jungle Conservation Reserve, Koolpinyah Station and Melville Island (Russell-Smith 1991). These are the only known mainland records of this species (Holmes et al. 2005; Russell-Smith 1991). Both Bankers Jungle and Black Creek are spring-fed monsoon rainforest patches on the margin of the Adelaide River Floodplain (Holmes et al. 2005; Russell-Smith 1991).

Ptychosperma bleeseri Burret, Darwin palm

Not yet assessed by the IUCN. The species is listed as endangered under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and specially protected under sections 45 and 47 of the Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 1993 (Hay 1997; Parks & Wildlife Commission).

The palm is found in only eight small rainforest patches southeast of Darwin, within the Adelaide and Howard River catchments (Barrow et al. 1993; Dept. NT Parks & Wildlife Comm.; Liddle et al. 2006). Palm habitats occur in an area 30 km long by 20 km wide forming a total area of 40 ha (Dept. NT Parks & Wildlife Commission; Liddle et al. 2006). Three of the eight patches occur within the Black Jungle Conservation Reserve: (Barrow et al. 1993; Parks & Wildlife Commission) Black Creek, portions of rainforest at Crocodile Creek and BJ3 and are listed in the Register of the National Estate under the Australian Heritage Commission Act 1975 (Parks & Wildlife Commission). The remaining patches occur on freehold or pastoral lease land (Dept Env & Heritage 2003; Liddle et al. 2006; Parks & Wildlife Commission). P. bleeseri, commonly known as the Darwin Palm, has a slender growth habit with a height of up to 12 m (Liddle et al. 2006). The multiple green trunks are 3 – 6 cm wide and the feathery fronds have leaflets that grow up to 1.5 m long (Liddle et al. 2006). Flowering spikes are produced in the dry season, April to August, with the main fruiting period occurring between August and December (Dept. Env. & Heritage 2003; Liddle et al. 2006). Threats to the species include invasion by weeds, habitat degradation caused by feral animals including grazing of seedling by pigs and changes in water quantity and quality due to changing land use in the catchment (Barrow et al. 1993; Liddle et al. 2006). Intense fires can also threaten regeneration by eliminating adult plants and preventing seedling establishment (Barrow et al. 1993; Dept. Env. & Heritage; Liddle et al. 2006).

Typhonium johnsonianum A. Hay and S.M. Taylor

Family: Aracea Order: Arales Red List Category and criteria: Vulnerable D1 and 2 T. johnsonianum is known only by 2 specimens collected in 1993 and 1994, both within the Black Jungle Reserve in the Northern Territory, Australia (Hay 1997; Hay et al. 1996). The extent of occurrence and area of occupancy for the species have been estimated as less than 100 and 10 km2 respectively (Hay 1997; Hay et al. 1996). This species is known exclusively from the reserve, surrounding threats such as expanding agriculture, overgrazing and mining are not likely to affect this species (Hay 1997). Although T. johnsonianum was found in wet monsoon forest with a high water table during the wet season, conditions are much different in the dry season and fires, therefore, could be a serious threat, considering the restricted area and number of individuals currently known (Hay 1997; Hay et al. 1996). T. johnsonianum is therefore listed as Vulnerable under D1 and D2 (IUCN Red List; Hay 1997; Hay et al. 1996). The species is found in open grassy clearings between Acacia auriculiformis and Melaleuca forest with Lophostemon lactifluus near the flood plain edge, in sandy well drained soil with seasonal inundation (Hay 1997; Hay et al. 1996).

Nososticta koolpinyah, (Order: Odonata) Koolpinyah threadtail dragonfly

Watson and Theischinger 1984. Data Deficient ver 3.1 The species is endemic to Australia and the range includes Black Jungle, Koolpinyah Station and Melville Island in the Northern Territory and is considered as a rare to scarce species which frequents freshwater streams and terrestrial habitats (Endersby 2012; Hawking 2009). Threats to this dragonfly include farming, agro-industry and mining which is believed to negatively impact on the habitat of this species (Hawking 2009).

See also

Protected areas of the Northern Territory

References

- ^ "Place Names Register Extract for Black Jungle / Lambells Lagoon Conservation Reserve". NT Place Names Register. Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Terrestrial Protected Areas by Reserve Type in Northern Territory (2016)". CAPAD 2016. Australian government. 2016. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Australian Heritage Council, Department of the Environment. Online accessed: 14 May 2015: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/

- Barrow, P., Duff, G., Liddle, D. and Russell-Smith, J. 1993. Threats to monsoon rainforest habitat in northern Australia: the case of Ptychosperma bleeseri Burret (Aracaceae). Australian Journal of Ecology, Vol. 18 (4), pp. 463 – 471

- ATNS Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements Projects. 2011. Black Jungle/Lambells Lagoon Conservation Reserve Indigenous Land Use Agreement. Online accessed 14 May 2015 http://www.atns.net.au/objects/DI2004_052.jpg

- Bureau of Meteorology 2006. Online accessed: 28 April 2015 http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/

- Brockwell, C.J. 2001. Archaeological settlement patterns and mobility strategies on the lower Adelaide River, Northern Australia. Thesis: Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Law, Business and Arts, Northern Territory University, Darwin, Australia.

- De La Rue, K. 2004. The Evolution of Darwin 1869 – 1911: A history of the Northern Territory's capital city during the years of South Australian administration. Charles Darwin University Press, Darwin, Australia.

- Department of Environment and Heritage 2003. Biodiversity – Threatened Species and Ecological Communities – Threatened Species Publications – Darwin palm Ptychosperma bleeseri

- Online accessed: 14 May 2015 http://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/threatened/publications/darwin-palm-ptychosperma-bleeseri

- Department of Land & Resource Management. 2013. www.lrm.nt.gov.au/__.../Sensitive-Veg-Factsheets_Monsoon_Feb2013.p

- Endersby I. 2012. Watson and Theischinger: the etymology of the dragonfly (Insecta: Odonata) names which they published. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of N.S.W., Vol. 145, nos. 443 and 444, pp. 34 – 53.

- Parks and Reserves (Framework For The Future) Act. Northern Territory. Database last updated: May 2015. Online accessed 20 May 2015 http://www5.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nt/consol_act/parftfa452/

- Hawking, J. 2009. Nososticta koolpinyah. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Ver.2014.3 Online accessed: 10 May 2015 www.iucnredlist.org.

- Hay, A. 1997. Two new species and a new combination in Australian Typhonium (Araceae Tribe Areae) Edinburgh Journal of Botany 54, 329–336.

- Hay, A. and Taylor, S.M. 1996. A new species of Typhonium Schott Araceae-Areae) from the Northern Territory, with notes on the conservation status of two Areae endemic to the Tiwi Islands. Telopea – Journal of Plant Systematics. Vol. 6 (4), pp. 563 - 567

- Holmes, J.,Bisa, D., Hill, A. and Crase B. 2005. A Guide to Threatened, Near Threatened and Data Deficient Plants in the Litchfield Shire of the Northern Territory. WWF – Australia, Sydney.

- Liddle, D.T., Brook, B.W., Matthews, J., Taylor, S.M. and Caley,P. 2006. Threat and response: A decade of decline in a regionally endangered rainforest palm affected by fire and introduced animals, Biological Conservation, Volume 132, Issue 3, Pages 362–375, ISSN 0006-3207, doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2006.04.028

- McGrath, A. 1987. Born in the Cattle – Aborigines in Cattle Country. Allen and Unwin Australia Pty Ltd. North Sydney, Australia.

- Northern Territory Government, Department of Land Resource Management. Sensitive Vegetation in the Northern Territory. 2013. Monsoon Rainforest. Online accessed: 12 May 2015 www.lrm.nt.gov.au/__.../Sensitive-Veg-Factsheets_Monsoon_Feb2013.pdf

- Northern Territory Government http://www.ntlis.nt.gov.au/placenames/view.jsp?id=2013

- Northern Territory Government – Sites of Conservation Significance https://web.archive.org/web/20150321041608/http://lrm.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/13928/12_adelaide.pdf

- Northern Territory Government. Adelaide River Conservation Reserves Joint Management Plan. August 2014. Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory. www.parksandwildlife.nt.gov.au

- Northern Territory Parks and Wildlife Commission http://www.parksandwildlife.nt.gov.au/manage/joint#.VT-PlosfrIU

- Northern Territory Government 2015 Department of Land Resource Management. Online accessed 12 May 2015: www.lrm.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/.../12_adelaide.pdf

- Ox Flux Australia & New Zealand Flux Research & Monitoring. On line accessed: 29 April 2015 http://data.ozflux.org.au

- Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory. A Trial Management Program for Ptychosperma bleeseri Burret in the Northern Territory of Australia. Online accessed: 12 May 2015 https://web.archive.org/web/20150324154920/http://www.lrm.nt.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0016/11185/management_program_for_ptychosperma_bleeseri.pdf

- Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory. Adelaide River Conservation Area. August 2011. Online accessed: 12 May 2015 www.lifestylent.nt.gov.au

- Place Names Committee of the Northern Territory http://placenames.nt.gov.au/origins/greater-darwin#b

- Russell-Smith, J. and Bowman, D.M.J.S. 1991. Conservation of monsoon rainforest isolates in the Northern Territory, Australia. Biological Conservation, Vol. 59, pp. 51 – 63

- Russell-Smith, J. 1991. Classification, species richness and environmental relations of monsoon rainforest in northern Australia. Journal of Vegetation Science 2, 259–278.

- Salmon, J. 2013. Drivers of change in Darwin's hinterland. Thesis, Faculty of Engineering, Health, Science and the Environment. Charles Darwin University

- Shapcott, A. 2000. Conservation and genetics in the fragmented monsoon rainforest in the Northern Territory, Australia: a case study of three frugivore-dispersed species. Australian Journal of Botany Vol. 48, 397–407.

- Shapcott, A. 1998. The genetics of Ptychosperma bleeseri, a rare palm from the Northern Territory, Australia. Biological Conservation, Vol. 5, pp. 203 – 209

- Wells, S.2003. Negotiating Place in Colonial Darwin – Interactions between Aborigines and whites, 1869 – 1911. Thesis, University of Technology, Sydney.