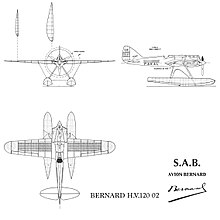

Bernard H.V.120

| H.V.120 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Role | Racing seaplane |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | Société des Avions Bernard |

| First flight | 25 March 1930 |

| Number built | 2 |

The Bernard H.V.120 was a racing seaplane designed and built by the French aircraft manufacturer Bernard. It was developed specifically to compete in the Schneider Trophy race.

The company developed it as a wooden single-seat mid-wing cantilever monoplane, equipped with twin floats and powered by a 1,680 hp (1,253 kW) Hispano Suiza 18R W-18 piston engine. Development was protracted, primarily as a result of engine-related difficulties, that delayed availability and thus did not permit the aircraft to race in the 1929 competition as intended. The first aircraft performed its maiden flight on 25 March 1930, four months after the race.

The test flight programme, while successfully demonstrating the ability to fly at 500 kmph (310 mph), was not trouble-free. The second aircraft was lost in a fatal crash during 1931; work continued with the first aircraft. During the early 1930s, the prototype was converted, and thus re-designated Bernard V.4, into a racing landplane; however, this aircraft would never actually fly as a result of funding having been pulled for the project.

Development

The Schneider Trophy competition, held annually throughout much of the interwar period, proved to be attractive to various aircraft manufacturers across Europe. For the 1929 race, it was intended for France to have been represented by two seaplanes, one that was produced by Nieuport while the other by Bernard.[1] Both projects were worked on with a high degree of secrecy and information was often intentionally vague to most external parties.[1] Despite both company's strenuous efforts, neither aircraft were ultimately able to participate at the 1929 event due to the failure of the engine manufacturer to deliver their intended powerplants on time.[1]

On 25 March 1930, the first H.V.120 conducted its maiden flight from Hourtin, roughly four months after the race.[1] Within the next 12 months, it demonstrated its ability to attain speeds as high as 500 kmph (310 mph).[2] Aside from the engine-related problems, development of the aircraft had encountered several technical issues; the weight of the finalised engine was so much that it necessitated the redesigning of both the engine mount and the forward fuselage.[citation needed] Several other changes were made, while the first aircraft had a three-bladed propeller, the second was fitted with a four-bladed Chauvière propeller instead. During July 1931, the second aircraft crashed into the water on its first flight, killing the pilot.[citation needed]

In 1933, the prototype was converted into a racing landplane, referred to as the Bernard V.4. The V.4 had widely spaced main landing gear with streamlined wheel spats.[citation needed] During December 1933, the V.4 was transported to Istres to try to achieve a French Air Ministry prize for a French aircraft to beat the world speed record before January 1934. It was due to make an attempt to fly on 27 December 1933, but strong winds kept the aircraft grounded. Further attempts in February 1934 to fly were thwarted by engine problems and lack of government finance. The project was abandoned without the aircraft having ever flown.[citation needed]

Design

The single-piece wing of the aircraft was entirely composed of wood and features laminar-type construction, akin to that of the Bernard 20 fighter aircraft.[1] Structurally, it used narrow box-girders that roughly corresponded to traditional spar. These girders, which varied in both height and length dependent upon their specific location within the wing, were fitted with plywood flanges and spruce webs that were glued together to produce a longitudinal multicellular structure.[3] This framework of the wing was attached to the formers of both the leading edge and trailing edge as well as the inter-spar ribs. The flanges were planed down to the sought profile, which was relatively thick and biconvex, before being covered with plywood.[4]

The centre section of each girder was enlarged and hollowed out to form the forward portion of the cockpit as well as a portion of the fuselage. The centre of the wing possessed considerable torsional resistance while the wingtips were noticeably more flexible.[4] The entire width of the wing's central section was traversed by four tubes, composed of steel, that terminated in sockets at each end. The wing was attached to the fuselage via the four rear sockets while the four forward sockets connected to the engine bearer.[4] Furthermore, the float gear was attached, via a duralumin frame, to the underside of the wing's central section. The ailerons, which were metal, were operated by torsion.[4]

The aircraft had an oval-section fuselage, the midsection of which was intentionally minimised in terms of its size.[4] Structural elements included a pair of box girders that formed two vertical walls; these were united via several frames of spruce and plywood. These girders consist of a pair of longerons, complete with spruce uprights and crosspieces, that were assembled by gussets and entirely covered by plywood. Both the top and bottom of the fuselage were also covered with plywood, which was stiffened via a series of longitudinal stringers.[5] A single-piece horizontal empennage was encased into the tip of the fuselage and secured via four bolts; it had a framework of two box spars and ribs and was covered with plywood. The fin, which shared a similar design, was integral with the fuselage.[6]

The floats were mounted in a similar fashion to that of a catamaran; they were connected to the central section of the wing by wooden panels and highly resistant steel tubing.[6] Furthermore, each float was connected with the wing via a pair of wires with elastic attachments that prevented abnormal stresses from being transferred through the wires; such forces could occur during a hard landing or in the event of the wing having suffered deformation.[6] Fuel was housed inside of both floats; in operation, the fuel from the left float would automatically transfer across to the right float, from which the fuel was pumped to the engine.[7]

It was powered by a single Hispano Suiza 18R inline piston engine, capable of producing up to 1,400 hp.[6] Installed within the nose of the aircraft, it was covered by a cowling that fused with the leading edge of the wing. The atypical engine arrangement required a purpose-designed mount, consisting of a cradle that was directly attached to the two lower forward sockets of the wing's centre section and supported by a pair of tubes that were attached to the two upper forward sockets of the wing.[8] A compact header tank was present that used air pressure to prevent fuel delivery issues while the aircraft was performing tight turns or high-G manoeuvres, although a prolonged bank could exceed its capabilities. Cooling was primarily achieved via sizable wing-mounted radiators; these covered three quarters of the wing's surface area.[9] A separate radiator on the side of the fuselage was present to cool the oil; just aft of the pilot's position was the oil tank.[2]

Variants

- H.V.120-01

- Prototype, first flew 25 March 1930 had a direct drive three-bladed propeller.

- H.V.120-02

- Fatal crash on first flight in July 1931, had a reduction gear to drive a four-bladed propeller

- V.4

- Prototype H.V.120 re-built as a landplane in 1933 with a 1,125 hp (839 kW) Hispano-Suiza 18Sb engine and shorter span wings, not flown.

Specifications (H.V.120-01)

Data from Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft,[10] National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics[11]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 8.24 m (27 ft 0 in)

- Wingspan: 8.65 m (28 ft 5 in)

- Height: 3.60 m (11 ft 10 in)

- Wing area: 11.00 m2 (118.4 sq ft)

- Max takeoff weight: 2,100 kg (4,630 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Hispano Suiza 18R W-18 inline piston engine, 1,253 kW (1,680 hp)

- Propellers: 3-bladed

Performance

- Maximum speed: 530 km/h (330 mph, 290 kn)

References

Citations

Bibliography

- The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Aircraft (Part Work 1982-1985). Orbis Publishing.

- "The Bernard 120 seaplane (French) : a 1400 hp single-seat monoplane racer" National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, 1 March 1931. NACA-AC-139,

93R19940.

Further reading

- Liron, Jean (1990). Les avions Bernard. Collection Docavia. Vol. 31. Paris, France: Éditions Larivière. ISBN 2-84890-065-2.

- Meurillon, Louis (November 1976). "La Coupe Schneider et la Société des Avions Bernard (5)" [The Schneider Cup and the Bernard Company, Part 5]. Le Fana de l'Aviation (in French) (84): 3–7. ISSN 0757-4169.

- Meurillon, Louis (December 1976). "La Coupe Schneider et la Société des Avions Bernard (6)" [The Schneider Cup and the Bernard Company, Part 6]. Le Fana de l'Aviation (in French) (85): 4–7. ISSN 0757-4169.

- Meurillon, Louis (January 1977). "La Coupe Schneider et la Société des Avions Bernard (7)" [The Schneider Cup and the Bernard Company, Part 7]. Le Fana de l'Aviation (in French) (86): 3–7. ISSN 0757-4169.

- Meurillon, Louis (February 1977). "La Coupe Schneider et la Société des Avions Bernard (8)" [The Schneider Cup and the Bernard Company, Part 8]. Le Fana de l'Aviation (in French) (87): 3–7. ISSN 0757-4169.