Belarusians

Belarusian: Беларусы | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| c. 9 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

(Belarusian ancestry) | 600,000[3][4]–155,000[5] |

| 521,443 (2010)[6] | |

| 275,763 (2001)[7] | |

| 105,404 (2020)[8] | |

| 55,929–60,445 (2023)[9][10] | |

| 66,476 (2010)[11] | |

| 61,000[12] | |

| 31,000[13] | |

| 31,000[14] | |

| 20,000[14] | |

| 15,565[15] | |

| 12,100[14] | |

| 11,828 (2017)[16] | |

| 10,054[14] | |

| 8,529[14] | |

| 7,500[14] | |

| 7,000[14] | |

| 7,000[14] | |

| 5,828[17] | |

| 2,833[18] | |

| 2,015[19] | |

| 2,000 | |

| 2,000[14] | |

| 1,560 (2006)[20] | |

| 1,168[21] | |

| 1,002 (2009)[22] | |

| 1,000 | |

| 973 (2016)[23] | |

| below 500[14] | |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Orthodox Christianity (majority), Roman Catholicism, Belarusian Greek Catholicism, Irreligion (minority) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other East Slavs (Poleshuks, Podlashuks, Russians, Ukrainians) | |

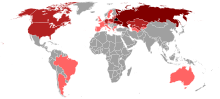

Belarusians (Belarusian: беларусы, romanized: biełarusy [bʲeɫaˈrusɨ]) are an East Slavic ethnic group native to Belarus. They natively speak Belarusian, an East Slavic language. More than 9 million people proclaim Belarusian ethnicity worldwide.[24] Nearly 7.99 million Belarusians reside in Belarus,[1][2] with the United States[3][4][5] and Russia[6] being home to more than 500,000 Belarusians each. The majority of Belarusians adhere to Eastern Orthodoxy.

Name

During the Soviet era, Belarusians were referred to as Byelorussians or Belorussians (from Byelorussia, derived from Russian "Белоруссия"). Before, they were typically known as White Russians or White Ruthenians (from White Russia or White Ruthenia, based on "Белая Русь"). Upon Belarusian independence in 1991, they became known as Belarusians (from Belarus, derived from "Беларусь"), sometimes spelled as Belarusans,[25] Belarussians[26] or Belorusians.[26]

The term White Rus' (Белая Русь, Bielaja Ruś), also known as White Ruthenia or White Russia (as the term Rus' is often conflated with its Latin forms Russia and Ruthenia), was first used in the Middle Ages to refer to the area of Polotsk.[26][27] The name Rus' itself is derived from the Rus' people which gave the name to the territories of Kievan Rus'.[28] The chronicles of Jan of Czarnków mention the imprisonment of Lithuanian grand duke Jogaila and his mother at "Albae Russiae, Poloczk dicto" in 1381.[29] During the 17th century, the Russian tsars used the term to describe the lands added from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[30] However, during the Russian Civil War, the term White Russian became associated with the White movement.[26]

Geographic distribution

Belarusians are an East Slavic ethnic group, who constitute the majority of Belarus' population.[26] Belarusian minority populations live in countries neighboring Belarus: Ukraine, Poland (especially in the Podlaskie Voivodeship), the Russian Federation and Lithuania.[26] At the beginning of the 20th century, Belarusians constituted a minority in the regions around the city of Smolensk in Russia.

Significant numbers of Belarusians emigrated to the United States, Brazil and Canada in the early 20th century. During Soviet times (1917–1991), many Belarusians were deported or migrated to various regions of the USSR, including Siberia, Kazakhstan and Ukraine.[31]

Since the 1991 breakup of the USSR, several hundred thousand Belarusians have emigrated to the Baltic states, the United States, Canada, Russia, and EU countries.[32]

Languages

The two official languages of Belarus are Belarusian and Russian. Russian was made co-official with Belarusian after the 1995 Belarusian referendum, which also established that the flag (with the hammer and sickle removed), anthem, and coat of arms would be those of the BSSR. The OSCE Parliamentary Assembly stated that the referendum violated international standards. Members of the opposition claimed that the organization of the referendum involved several serious violations of legislation, including a violation of the constitution.[33]

Genetics

Belarusians, like most Europeans, largely descend from three distinct lineages:[34] Mesolithic hunter-gatherers, descended from a Cro-Magnon population that arrived in Europe about 45,000 years ago;[35] Neolithic farmers who migrated from Asia Minor during the Neolithic Revolution 9,000 years ago;[36] and Yamnaya steppe pastoralists who expanded into Europe from the Pontic–Caspian steppe in the context of Indo-European migrations 5,000 years ago.[34]

History

The Neolithic and the Bronze Age

In the Neolithic most of present-day Belarus was inhabited by Finno-Ugrians. Indo-European population appeared in the Bronze Age.[37][38]

Early Middle Ages

In the Iron Age, the south of present-day Belarus was inhabited by tribes belonging to the Milograd culture (7th–3rd century BC) and later Zarubintsy culture. Some considered them to be Balts.[39] Since the beginning of common era, these lands were penetrated by the Slavs, a process that intensified during the migration period (4th century).[39] A peculiar symbiosis of Baltic and Slavic cultures took place in the area, but it was not a fully peaceful process, as evidenced by numerous fires in Balts' settlements in the 7th-8th centuries.[40] According to Russian archaeologist Valentin Sedov, it was intensive contacts with the Balts that contributed to the distinctiveness of the Belarusian tribes from the other Eastern Slavs.[41]

The Baltic population gradually became Slavic, undergoing assimilation, a process that for eastern and central Belarus ended around the 12th century.[41] Belarusian lands in the 8th-9th centuries were inhabited by 3 tribal unions: the Krivichs, Dregoviches and Radimichs. Of these, the Krivichs played the most important role; Polotsk, founded by them, was the most important cultural and political center during this period. The principalities formed at that time on the territory of Belarus were part of Kievan Rus'. The process of the beginning of the East Slavic linguistic community and the separation of Belarusian dialects slowly took place.[41]

In the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

As a result of Lithuanian expansion, the lands of Belarus became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. This fact accelerated the Slavicization of the Baltic population. Between the 13th and 16th centuries, a distinct Ruthenian language was formed.[42] It is called "Old Belarusian language" by Belausian researchers and "Old Ukrainian" by the Ukrainian ones. The rulers and the elite of the Grand Duchy adopted elements of Ruthenian culture, primarily Ruthenian language, which became the main language of writing. Belarusians began to emerge as a nationality during the 13th and 14th centuries in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania mostly on the lands of the upper basins of Neman River, Dnieper River, and the Western Dvina River.[43] The Belarusian people trace their distinct culture to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, earlier Kievan Rus' and the Principality of Polotsk.[44]

Litvin was a term used to describe all residents of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, primarily those belonging to the noble state, without distinction of ethnicity or religion. At the same time, the term Ruthenian (Rusyn) was in use, referring primarily to all persons professing Orthodoxy; later since the end of the 16th century it took on a broader meaning, and also referred to all the persons of Eastern Slavic origin, regardless of their religion. At the same time, there was a geographical division within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania between Lithuania proper and Rus'. However, it did not correspond to an ethnic or confessional division, as Lithuania proper included a large part of central and western Belarus with cities such as Polotsk, Vitebsk, Orsha, Minsk, Barysaw and Slutsk, while the remaining lands inhabited by Slavs were called Rus.[45] From the 17th century onward, the name White Ruthenia (Belarusian: Белая Русь, romanized: Biełaja Ruś) spread, which initially referred to the territory of today's Eastern Belarus (Polotsk, Vitebsk). The term "Belarusians", "Belarusian faith" and "Belarusian speech" also appeared at that time.[45][46] As stated by historian Andrej Kotljarchuk, the first person who called himself "Belarusian" was Calvinist writer Salomon Rysinski (Solomo Pantherus Leucorussus). According to his words, he was born "in richly endowed with forests and animals Ruthenia near the border to frigid Muscovy" and doctorated at the University of Altdorf.[47]

From the 1630s, Old Belarusian (Ruthenian) started to be replaced by the Polish language, as a result of the Polish high culture acquiring increasing prestige in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. In 1697, Ruthenian was removed as one of the Grand Duchy's official languages.[48] By the 17th century, Muscovites began encouraging the use of the word Belarusian and viewed the Belarusians as Russians and their language as a Russian dialect.[46] This was done to legitimize Russian attempts of conquering the eastern lands of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth under the pretense of unifying all Russian lands.[46] During three partitions of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (1772, 1793 and 1795) most of the territories of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were annexed by the Russian Empire.

In the Russian Empire

Following the destruction of Poland–Lithuania with the Third Partition in 1795, Empress Catherine of Russia created the Belarusian Governorate from the Polotsk and Mogilev Governorates.[27] However, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia banned the use of the word Belarus in 1839, replacing it with the designation Northwestern Krai.[49] Due to the ban, various different names were used for naming the inhabitants of those territories.[46] It was part of the Pale of Settlement, which was the region where Jews were allowed permanent residency.

20th century

During World War I and the fall of Russian Empire, a short-lived Belarusian Democratic Republic was declared in March 1918. Thereafter, modern Belarus' territory was split between the Second Polish Republic and Soviet Russia during the Peace of Riga in 1921. The latter created the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, which was reunited with Western Belarus during World War 2 and lasted until the dissolution of the Soviet Union, which was ended by the Belovezh Accords in 1991. The modern Republic of Belarus exists since then.

More than two million people were killed in Belarus during the three years of German occupation in 1941–44, around a quarter of the region's population,[50] or even as high as three million killed or thirty percent of the population.[51]

Cuisine

Belarusian cuisine shares the same roots as the cuisines of other Eastern and Northern European countries.[citation needed]

See also

- List of Belarusians (ethnic group)

- Demographics of Belarus

- Dregovichs

- Krivichs

- Litvin

- Radimichs

- History of Belarus

- Belarusian Americans

References

- ^ a b "Changes in the populations of the majority ethnic groups". belstat.gov.by. Archived from the original on 28 July 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- ^ a b "Demographic situation in 2015". Belarus Statistical Office. 27 January 2016. Archived from the original on 3 February 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ a b Garnett, Sherman W. (1999). Belarus at the Crossroads. Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. ISBN 978-0-87-003172-4.

- ^ a b Kipel, Vituat. "Belarusan americans". World Culture Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 28, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Country: United States: Belarusians". Joshua Project. 2016. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ^ a b "All-Russian population census 2010 population by nationality, sex and subjects of the Russian Federation". Demoscope Weekly (in Russian). Archived from the original on December 28, 2014. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ "Всеукраїнський перепис населення 2001 - Результати - Основні підсумки - Національний склад населення". 2001.ukrcensus.gov.ua. Archived from the original on 2 January 2016. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Populacja cudzoziemców w Polsce w czasie COVID-19". Archived from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2022-01-20.

- ^ "Population by ethnicity at the beginning of year – Time period and Ethnicity | National Statistical System of Latvia". data.stat.gov.lv. Archived from the original on 2023-08-11. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ^ "Latvijas iedzīvotāju sadalījums pēc nacionālā sastāva un valstiskās piederības, 01.01.2023. - PMLP". Archived from the original on 2023-06-10. Retrieved 2023-06-10.

- ^ Перепись населения Республики Казахстан 2009 года. Краткие итоги. (Census for the Republic of Kazakhstan 2009. Short Summary) (PDF) (in Russian). Republic of Kazakhstan Statistical Agency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ "Bevölkerung in Privathaushalten nach Migrationshintergrund im weiteren Sinn nach ausgewählten Geburtsstaaten". Statistisches Bundesamt. Archived from the original on 2022-05-31. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ "Gyventojų skaičius metų pradžioje. Požymiai: Tautybė - Rodiklių duomenų bazėje". Archived from the original on 2012-09-06. Retrieved 2011-12-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Как живешь, белорусская диаспора?". Belarus Time (in Belarusian). March 13, 2012. Archived from the original on March 13, 2012.

- ^ "Ethnic Origin (264), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3), Generation Status (4), Age Groups (10) and Sex (3) for the Population in Private Households of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2011 National Household Survey". 12.statcan.gc.ca. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 2018-12-24. Retrieved 2017-08-02.

- ^ "Rahvaarv rahvuse järgi, 1. jaanuar, aasta - Eesti Statistika". Stat.ee. Archived from the original on 4 January 2018. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Población extranjera por Nacionalidad, provincias, Sexo y Año". Archived from the original on 2021-03-02. Retrieved 2021-04-12.

- ^ "Utrikes födda efter födelseland och invandringsår" [Foreign-born by country of birth and year of immigration] (XLS). Statistics Sweden (in Swedish). 31 December 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents".

- ^ "20680-Ancestry (full classification list) by Sex - Australia". 2006 Census. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel download) on March 10, 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

- ^ "Usually resident population by citizenship and age on 1 January - Both sexes" (PDF). 5 June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2011.

- ^ "POPULAÇÃO ESTRANGEIRA RESIDENTE EM TERRITÓRIO NACIONAL - 2009" (PDF). Statistics Portugal (in Portuguese). January 1, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-08-26. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ "CBS StatLine - Population; sex, age and nationality, 1 January". Statline.cbs.nl. Archived from the original on 2 August 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "The Belarusian Diaspora Awakens | German Marshall Fund of the United States". www.gmfus.org. Archived from the original on 2023-08-11. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ ""Як нас заве сьвет — "Беларашэн" ці Belarus(i)an?"". www.svaboda.org. Archived from the original on 2016-07-28. Retrieved 2016-07-28.

- ^ a b c d e f Cole, Jeffrey E. (2011-05-25). Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-59884-303-3. Archived from the original on 2023-01-16. Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ^ a b Kovalenya, A. A. (2022-05-15). Belarus: pages of history. Litres. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-5-04-162594-8. Archived from the original on 2023-05-19. Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ^ Duczko, Wladyslaw (2004). Viking Rus. Brill Publishers. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-90-04-13874-2. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Vauchez, Dobson & Lapidge 2001, p. 163

- ^ Plokhy 2001, p. 327

- ^ "Belarus: Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union - EuroDocs". eudocs.lib.byu.edu. Archived from the original on 2023-01-15. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ Heleniak, Timothy (2002-10-01). "Migration Dilemmas Haunt Post-Soviet Russia". migrationpolicy.org. Archived from the original on 2023-07-08. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ "› Беларуская Салідарнасьць » Сяргей Навумчык: Парушэньні ў часе рэфэрэндуму - 1995". Bielarus.net. Archived from the original on 2020-10-16. Retrieved 2017-01-10.

- ^ a b Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; Rohland, Nadin; Mallick, Swapan; Llamas, Bastien; Brandt, Guido; Nordenfelt, Susanne; Harney, Eadaoin; Stewardson, Kristin; Fu, Qiaomei (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (August 2019). "The first Europeans weren't who you might think". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (21 February 2017). "Thousands of horsemen may have swept into Bronze Age Europe, transforming the local population". Science. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ История Беларуси. С древнейших времен до 2012 г. / под ред. Е. К. Новика. — 3-е изд. — Минск: Вышэйшая школа, 2012. — С. 12, 13, 20. — 542 с.

- ^ Гісторыя Беларусі: У 2 ч. Частка 1. Са старажытных часоў да канца XVIII ст. / І. П. Крэнь і інш. — Мінск: РІВШ БДУ, 2000. — С. 303—304. — 656 с.

- ^ a b Shved & Grzybowski 2020, p. 54.

- ^ Pankowicz 2004, p. 90.

- ^ a b c Shved & Grzybowski 2020, p. 55.

- ^ Shved & Grzybowski 2020, p. 57-58.

- ^ Беларусы : у 10 т. / Рэдкал.: В. К. Бандарчык [і інш.]. — Мінск : Беларус. навука, 1994–2007. — Т. 4 : Вытокі і этнічнае развіццё... С. 36, 49.

- ^ "Belarus - Culture, Traditions, Arts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2023-07-15. Retrieved 2023-08-11.

- ^ a b Shved & Grzybowski 2020, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Fishman, Joshua; Garcia, Ofelia (2011-04-21). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts (Volume 2). Oxford University Press. p. 385. ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1.

- ^ "The Orthodoxy in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Protestants of Belarus". www.belreform.org. Retrieved 2024-08-19.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2009). The Politics of Language and Nationalism in Modern Central Europe. pp. 153, 156, 180.

- ^ Everett-Heath, John (2018-09-13). The Concise Dictionary of World Place-Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-256243-2. Archived from the original on 2023-08-11. Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ^ "The tragedy of Khatyn - Genocide policy". SMC Khatyn. 2005. Archived from the original on 2015-03-10.

- ^ Donovan, Jeffrey (2005-05-04). "World War II -- 60 Years After: Legacy Still Casts Shadow Across Belarus". www.rferl.org. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

Bibliography

- Pankowicz, Andrzej (2004). "Spór o genezę narodu białoruskiego. Perspektywa historyczna" [The dispute over the genesis of the Belarusian nation. A historical perspective]. Krakowskie Studia Międzynarodowe (in Polish). 4: 89–106.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2001). The Cossacks and Religion in Early Modern Ukraine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-924739-0.

- Savchenko, Andrew (2009). Belarus - A Perpetual Borderland. Leiden-Boston: Brill.

- Shved, Viachaslau; Grzybowski, Jerzy (2020). Historia Białorusi. Od czasów najdawniejszych do roku 1991 [History of Belarus. From the earliest times to 1991] (in Polish). Warsaw: WUW.

- Vauchez, André; Dobson, Richard Barrie; Lapidge, Michael (2001). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Routledge. ISBN 1-57958-282-6.

External links

Quotations related to Belarusians at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Belarusians at Wikiquote- Ethnographic Map (New York, 1953)

- CIA World Fact Book 2005