Battle of Vienna, Virginia

38°54′03″N 77°15′23″W / 38.9008351°N 77.2564224°W

| Battle of Vienna, Virginia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

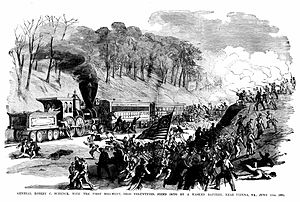

1st Ohio Infantry in action at Vienna, Virginia June 17, 1861 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Irvin McDowell Robert C. Schenck |

P. G. T. Beauregard Maxcy Gregg | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 274 | 750 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

8 killed 4 wounded | None | ||||||

The Battle of Vienna, Virginia was a minor engagement between Union and Confederate forces on June 17, 1861, during the early days of the American Civil War.

The Union was trying to protect the areas of Virginia opposite Washington, D.C., and established a camp at Vienna, at the end of a 15-mile (24.1 km) railroad to Alexandria. As Union Brig. Gen. Robert C. Schenck was transporting the 1st Ohio Infantry to Vienna by train, they were overheard by Confederate scouts led by Colonel Maxcy Gregg, who set up an ambush. They hit the train with two cannon shots, inflicting casualties of eight killed and four wounded, before the Union men escaped into the woods. The engineer had fled with the locomotive, so the Union force had to retreat on foot. The Confederates briefly attempted a pursuit in the dark, but it was called off.

Compared with later operations, the battle involved only small numbers, with the Union fielding 274 infantry, and the Confederates about 750 of infantry, cavalry and artillery. But it was widely reported by an eager press, and it worried the government, whose 90-day regiments were due to be disbanded.

Background

In the early morning of May 24, the day after the secession of Virginia from the Union was ratified by popular vote, Union forces occupied Alexandria, Virginia and Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. Union troops occupied the area up to distances of about 5 miles (8.0 km) from the river.[1] On June 1, a small U. S. Regular Army patrol on a scout as far as 8 miles (13 km) from their post at Camp Union in Falls Church, Virginia rode into Fairfax Court House, Virginia and fought a small and brief battle with part of a company of Virginia militia (soon to be Confederate Army infantry) at the Battle of Fairfax Court House.[2] The patrol brought back to the Union Army commanders an exaggerated estimate of Confederate strength at Fairfax Court House. Together with an even smaller affair the same night at a Union outpost in Arlington, the Battle of Arlington Mills,[2] the Fairfax Court House engagement made Union commanders hesitate to extend their bridgehead into Virginia.[3][4][5]

On June 16, a Union force of Connecticut infantry under Brig. Gen. Daniel Tyler rode over about 17 miles (27 km) of the Alexandria, Loudon and Hampshire Railroad line between Alexandria, Virginia and two miles (3 km) past Vienna, Virginia. They reported the line clear, although one soldier had been wounded by a shot from ambush.[6] Confederate forces were in the area, however, and it was apparent to Union Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell who was in charge of the department that the railroad would not remain safe without a guard force, especially because he had received information that the Confederates planned to obstruct it.[7][8] On June 17, McDowell sent Brig. Gen. Schenck with the 1st Ohio Infantry under the immediate command of Col. Alexander McDowell McCook[9] to expand the Union position in Fairfax County.[5] Schenck took six companies over the Alexandria, Loudon and Hampshire Railroad line, dropping off detachments to guard railroad bridges between Alexandria, Virginia and Vienna, Virginia. As the train approached Vienna, about 4 miles (6.4 km) north of Fairfax Court House and 15 miles (24 km) from Alexandria, 271 officers and men remained with the train.[9][10][11][12]

On the same day, Confederate Col. Gregg took the 6–month 1st South Carolina Infantry Regiment, about 575 men, two companies of cavalrymen (about 140 men) and a company of artillery with two artillery pieces (35 men), about 750 men in total, on a scouting mission from Fairfax Court House toward the Potomac River.[5][7][12][13] On their return trip, at about 6:00 p.m., the Confederates heard the train whistle in the distance. Gregg moved his artillery pieces to a curve in the railroad line between the present locations of Park and Tapawingo Streets in Vienna and placed his men around the guns.[5][14][15] Seeing this disposition, an elderly local Union sympathizer ran down the tracks to warn the approaching train of the hidden Confederate force. The Union officers mostly ignored his warning and the train continued down the track.[5] In response to the warning, an officer was placed on the forward car as a lookout.[16]

Battle

The Union soldiers were riding open gondola or platform cars as the train backed down the track toward Vienna.[5] As the train rounded the curve, one of the men spotted some Confederate cavalrymen on a nearby hill. As the Ohio soldiers prepared to shoot at the horsemen, the Confederates fired their cannons from their hiding place around the curve. The Union force suffered several casualties but were spared from incurring even more by the slightly high initial cannon shots and by quickly jumping from the slow–moving train and either running into nearby woods or moving into protected positions near the cars.[16]

Schenck ordered Lieutenant William H. Raynor to go back to the engine and have the engineer take the train out of range in the other direction. Schenck quickly followed Raynor. Raynor had to help loosen the brakes. Because the brakeman had uncoupled most of the cars, the engineer left them. He did not stop for the Union soldiers to catch up but continued all the way back to Alexandria. Schenck now had no means of communication and had to have the wounded men carried back to their camp in blankets by soldiers on foot. The regiment's medical supplies and instruments had been left on the train.[16]

Many of the Union infantrymen took shelter behind the cars and tried to return fire against the Confederate force amid a confusion of conflicting orders.[16] McCook reorganized many of them in the woods.[17] Soon after the initial cannon shots and reorganization of Union forces in the woods, the two forces withdrew.[18]

As darkness fell, the Union force was able to retreat and to elude Confederate cavalry pursuers in the broken terrain. The Confederate pursuit also was apparently called off early due to apprehension that the Union force might be only the advance of a larger body of troops and because the Confederate force was supposed to return to their post that night.[17][19] Confederates took such supplies and equipment as were left behind and burned a passenger car and five platform cars that had been left behind.[19][20] When the Union commanders at Arlington got word of the attack, they sent wagons to bring back the wounded and the dead but these did not reach the location of the fighting. The next day, a Union sympathizer picked up the bodies of six of the Ohio men and brought them into the Union camp.[20]

Aftermath

The Union force suffered casualties of eight soldiers killed and four wounded.[14][16][19] The Confederates reported no casualties.[21]

The Union officers were criticized for not sending skirmishers in front of the train which had moved slowly along the track and for disregarding the warning given to them by the local Union sympathizer.[22] The Battle of Vienna followed the Union defeat at the Battle of Big Bethel only a week earlier and historian William C. Davis noted that "the press were much agitated by the minor repulse at Vienna on June 17, and the people were beginning to ask when the Federals would gain some victories."[23]

Historian Charles Poland, Jr. says the Battle of Fairfax Court House, the Battle of Arlington Mills, the Battle of Vienna, Virginia and several other brief clashes in the area at this time "were among the antecedents of the forthcoming first battle at Bull Run."[24] He also said that the battle has been "cited as the first time the railroad was used in warfare."[20] He no doubt was referring to the use of the railroad for troop movements or involvement in combat or both because some use of railroads for moving ammunition and supplies was made during the Crimean War.[25]

Further engagements took place at Vienna on July 9, 1861, and on July 17, 1861, as Union forces began their slow march to Manassas, Virginia and the First Battle of Bull Run (Battle of First Manassas).[26]

The railroad, which had eventually become the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad, was abandoned in 1968 and later turned into the Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Trail.[27] A historical marker that the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority erected near the Trail stands at the battle site, about 0.25 miles (0.40 km) east of the crossing of the Trail and Park Street.[28]

Commemorations

The Town of Vienna has given the name of "Battle Street" to a street near the battle site.[29] To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the battle, the Town hosted in 1961 a battle reenactment that featured a steam train that operated on the Washington and Old Dominion Railroad's tracks, which were still in active use.[30] The Town also commemorated the 125th anniversary of the battle in 1986.[31] On June 18, 2011, the Town and other organizations presented a reenactment of the battle near its site to commemorate the battle's 150th anniversary.[32] That reenactment featured a replica steam locomotive that had been leased from the Town of Strasburg, Virginia for $2,500 and transported to Vienna.[30]

Notes

- ^ Weigley, p. 39.

- ^ a b Long, p. 81.

- ^ Long, pp. 81–86.

- ^ Connery, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e f Poland, p. 44.

- ^ Davis, p. 70.

- ^ a b Lossing and Benson, p. 525.

- ^ Tomes, p. 323.

- ^ a b Crafts, p. 235.

- ^ Poland, p. 44 says the number was 274. Yet Poland says in a footnote on p. 84 that Schenck left camp with 697 and detached 387 for guard duty, which would have left him with 310 men. Given Eicher's and Davis's number of 271 for the remaining Union force, the 274 number Poland gives on p. 44 should be closer to the correct number of men on the train as it approached Vienna.

- ^ Eicher, p. 78, gives the slightly different figure of 271 men, which actually coincides with General Schenck's report.

- ^ a b Davis, 1977, p. 71

- ^ Scott, pp. 128–130.

- ^ a b Eicher, p. 78

- ^ Williams, p. 8

- ^ a b c d e Poland, p. 45.

- ^ a b Tomes, p. 325.

- ^ Tomes, pp.325-326.

- ^ a b c Lossing, 1866, p. 526

- ^ a b c Poland, p. 46

- ^ Hotchkiss, 1899, p. 94.

- ^ Poland, p. 47

- ^ Davis, 1977, p. 72

- ^ Poland, p. 43.

- ^ Wolmar, Christian. The Railways and War. Retrieved June 12, 2011

- ^ Long, 1971, pp. 92, 96

- ^ Williams, p. 131

- ^ Historical marker at battle site: "Civil War Action at Vienna". HMdb.org: The Historical Marker Database. Archived from the original on 2012-10-13. Retrieved 2013-02-02.

- ^ Coordinates of Battle Street in Vienna: 38°53′54″N 77°15′36″W / 38.8984606°N 77.2600108°W

- ^ a b Voth, Sally (June 14, 2011). "Vienna borrows Train Raid replica: Town locomotive to be used in re-enactment". Northern Virginia Daily. Strasburg, Virginia. Archived from the original on 2013-04-11. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ Hendry, Erica R. (January 19, 2011). "Battle, Secession Vote Re-Enactments Planned For Civil War Commemoration: In Vienna, activities to commemorate the 150th anniversary of The Civil War begin in May". Vienna Patch. Vienna, Virginia. Archived from the original on 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ^ "Battle of Vienna Reenactment". Town of Vienna, Virginia government. Archived from the original on 2013-04-09. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

References

- Connery, William S. Civil War Northern Virginia 1861. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2011. ISBN 978-1-60949-352-3.

- Crafts, William August (1867). The southern rebellion: being a history of the United States from the Commencement of President Buchanan's administration through the War for the Suppression of the Rebellion. Vol. 1. Boston: Samuel Walker & Co. OCLC 6007950. Retrieved February 2, 2013. At Google Books.

- Davis, William C. Battle at Bull Run: A History of the First Major Campaign of the Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8071-0867-7.

- Eicher, David J. The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-84944-5.

- Hotchkiss, Jed. Clement A. Evans, ed. Confederate Military History. vol. III. Atlanta: Confederate Publishing Company, 1899. OCLC 1004885555

- Long, E. B. The Civil War Day by Day: An Almanac, 1861–1865. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1971. OCLC 68283123.

- Lossing, Benson John; Barritt, William (1866). Pictorial history of the civil war in the United States of America'. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: George W. Childs. OCLC 1007582. Retrieved February 2, 2013. At Google Books.

- Poland, Charles P. Jr. (2004). The Glories Of War: Small Battles And Early Heroes Of 1861. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 1418440671. At Google Books.

- Tomes, Robert (1864–1867). The War with the South: A History of the Great Rebellion. Vol. 1. New York: Virtue and Yorston. OCLC 476284. Retrieved February 2, 2013. At Google Books.

- Scott, Robert Nicholson, et al., United States War Department (1880). The War of the Rebellion: a compilation of the official records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Vol. II. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. OCLC 427057. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) At Google Books. - Weigley, Russell F. A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861–1865. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-253-33738-0.

- Williams, Ames W. (1989). The Washington and Old Dominion Railroad. Arlington, Virginia: Arlington Historical Society. ISBN 0926984004. Retrieved 2013-03-05. At Google Books.