Battle of Sesimbra Bay

| Battle of Sesimbra Bay | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585) | |||||||

Sesimbra Bay as seen today. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

11 galleys, 1 carrack, Fort and various shore defenses |

5 galleons, 2 prizes | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 carrack captured, 2 galleys sunk, 1 fort immobilized, 800 killed or wounded[3] | 12 killed, 30 wounded[4] | ||||||

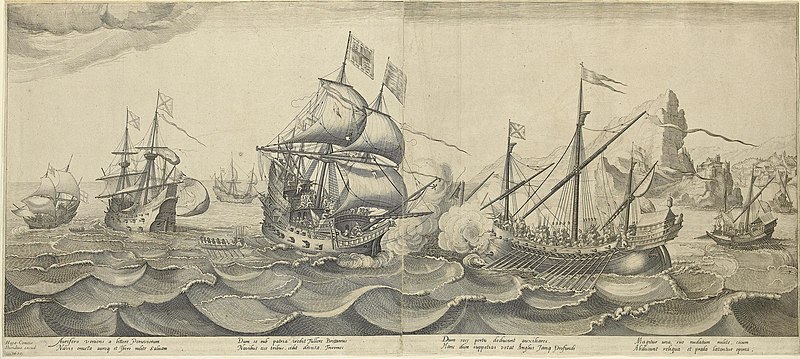

The Battle of Sesimbra Bay was a naval engagement that took place on 3 June 1602, during the Anglo-Spanish War. It was fought off the coast of Portugal (then within the Iberian Union) between an English naval expeditionary force sent out with orders by Queen Elizabeth I to prevent any further Spanish incursions against Ireland or England itself. The English force under Richard Leveson and William Monson met a fleet of Spanish galleys and a large carrack at Sesimbra Bay commanded by Álvaro de Bazán and Federico Spinola. The English were victorious in battle, sinking two galleys, forced the rest to retreat, neutralized the fort, and captured the carrack. It was the last expedition to be sent to Spain by orders of the Queen before her death the following year.[5]

Background

In order to prevent another Spanish invasion of Ireland, Queen Elizabeth I decided to fit out another fleet. Sir Richard Leveson was chosen for this command as he had defeated the Spanish under Pedro de Zubiaur at Castlehaven and successfully blockaded Kinsale from any further reinforcement later leading to the victory there early in 1602. He was to command a fleet of nine English and twelve Dutch ships, which were "to infest the Spanish coast." The Dutch ships were, however, late in joining. Leveson left his vice-admiral Sir William Monson to wait for the Dutch while he put to sea with only five ships on 19 March.[6] Within two or three days the queen sent orders to Monson to sail at once to join his admiral, for she had word that "the silver ships had arrived at Terceira" but they had in fact arrived and left again.[2][4]

Federico Spinola, younger brother of Ambrogio Spinola, had distinguished himself greatly as a soldier in the Army of Flanders and, in 1599, had successfully voyaged through the English Channel passing the Straits of Dover unmolested. Buoyed by this achievement he had indulged Philip III of Spain, the Duke of Lerma and Martín de Padilla in a vision of a massive galley-borne invasion of England from Flanders. However the council brought him down to a mere eight galleys, provided at Spinola's expense. He was on his way from San Lucar to Lisbon but was diverted by the Viceroy of Portugal to see to the protection of the richly-laden Portuguese carrack São Valentinho anchored in the bay at Sesimbra.[4]

It was not until the end of May that the two English squadrons met each other. On 1 June the English were off Lisbon with two captured Spanish prizes when word reached them that a large carrack and eleven galleys were in the vicinity of Sesimbra Bay. Some of the English ships had been sent home, mainly due to disease and/or unseaworthiness; others had separated and they too went back home. There were now only five ships in total with Leveson.[3]

Battle

On the morning of 3 June, Monson and Leveson found the Spanish ships strongly posted under the guns of Fort Santiago of Sesimbra and the old but armed moorish Sesimbra Castle further inland on a hill. The Spanish fleet consisted of eight galleys under the command of Spinola and another three under Álvaro de Bazán which had just recently arrived.[5] At mid-morning Monson with the ship Garland, Leveson with Warspite, Edward Manwaring with Dreadnought, followed by Nonpareil, Adventure and two captured prizes, entered the bay of Sesimbra.[2] As well as the Portuguese carrack São Valentinho, the Spanish galleys consisted of de Bazán's Christopher, Spinola's St Lewis, Forteleza, Trinidad, St John, Leva, Occasion, San Jacinto, Lazar, Padilla, and San Felipe.[7] The galleys had large cannons of sixty pounders in their bows and formed a tight defensive formation in the shallows around the carrack.[1]

As the English entered the bay, without hesitation they fired with everything they had at the anchored and secured galleys but made sure they were out of effective range of the Spanish 60-pounder (27 kg) cannon. Monson's Garland was able to bombard the Spanish galleys with her sixteen culverins forcing them to break formation. Much damage was caused but soon the galleys began to row side to side in the harbour in an attempt to avoid fire from Garland, which was now anchored. Leveson in Warspite however had problems with the wind and was soon being blown out of the roadstead despite efforts to keep Warspite in one position. Once out of effective range Leveson then rowed in a launch under fire and went on board Garland to join Monson and the rest of the fleet.[3][2]

When Bazán's galleys did break formation Dreadnought with her shallow draught sailed into the confusion and took them all on at close range with her eleven demi-culverins and ten sakers. Bazán had suffered significant losses with all three of his galleys damaged and was himself soon so badly wounded that there was much disorganization. Monson decided to concentrate his fire on Spinola's galleys. Within a few hours Garland and Nonpareil pounded them to the point that two of his galleys, Trinidad and Occasion, were soon burned and sunk, the captain of the latter being taken prisoner.[7] The galley slaves swam (if they could) to the English ships and Bazán's battered galleys managed to flee the action heading North.[1][4]

Capture of São Valentinho

The great carrack itself was surrounded and the remaining galleys under Spinola decided that the only sensible option was to retreat out of range from the bay. The rest of his galleys were already badly damaged, the galley slaves had been exhausted to the point of near death.[4] To the surprise of the English the fire from Fort Santiago de Sesimbra began to slacken. Nonpareil, Adventure, and occasional fire from Warspite had poured enough accurate fire into the fortress to put most of the guns out of action within an hour. With the destruction and retreat of the galleys it became clear that the carrack was lost.[5]

Under closer inspection the English realized that the carrack was a huge 1,700-ton vessel, São Valentinho, recently returned from the Portuguese Indies laden with goods. The castle and the various shore defences could not fire for fear of hitting their own ships as a result ineffectual fire continued throughout the battle. The English ships though kept up enough fire to silence the rest of the shore defences. Garland and Dreadnought sailed to port and starboard respectively of São Valentinho. She was soon boarded and within minutes the top deck had been secured with only a few losses and Monson wanted no more bloodshed.[2][8]

End

A parlay was offered by Monson which the Spanish reluctantly accepted and the battle was now effectively over. After Monson boarded the carrack, he was soon recognized by several Spanish officers as being their former prisoner. It turned out the galley Leva, which was present at the battle but had fled, was the same galley present at Battle of Berlengas Islands which had taken Monson prisoner. For Monson this was revenge.[7] At first the Spanish and Portuguese under Don Diego Lobo wanted to give the English just the cargo and leave the ship with their colours flying but Monson was adamant and wanted the whole ship but would release all the prisoners under terms.[4] He also forced the Spanish to cease firing and allow the English to leave unmolested. The Spanish could not burn the ship without being fired upon by the English and had São Valentinho surrounded by which two were powerful galleons.[2][6]

In this position the Spanish agreed to the English terms, to allow São Valentinho to be taken and the castle and shore defences to cease firing. The next day after a celebratory evening meal with the Spanish and Portuguese officers on board Garland, the English vessels towed out São Valentinho and with the victorious English sailing back to Plymouth unmolested.[1]

Aftermath

Casualties were heavy amongst the Spanish; around 800, most of which were from the galleys. The Portuguese carrack São Valentinho was a great prize in itself. The cargo on board totalled over a million ducats, about £44,000 which just about covered the costs of the summer campaigning.[8] São Valentinho was very similar in design to Madre de Deus which had been captured at Flores in 1592. English casualties were only twelve killed and thirty wounded, chiefly aboard Garland. William Monson was very nearly killed. He had fought in armor and had his doublet carried away by a ball.[7]

Monson and Leveson were both received as heroes on their return by Queen Elizabeth and the booty was given to the crown.[9] Leveson and Monson in return each received £3000 from the Queen and soon after their services were recommended to King James I both becoming admirals of the English Channel.[6] The Spanish viceroy of Portugal was incensed with the defeat and the loss of the carrack, he had Don Diego Lobo condemned to death but he escaped through a window with the aid of his sister and fled to Italy.[4]

Bazán would recover from his wounds and went on to command galleys in the Kingdom of Naples and later in life was to win fame in the Relief of Genoa. Spinola would suffer another defeat, this time at the hands of Sir Robert Mansell and a Dutch fleet in October of the same year in the Battle of the Narrow Seas in which his remaining six galleys that had escaped were intercepted and destroyed with only Spinola's escaping.[9]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Bicheno, p. 298.

- ^ a b c d e f Moltey, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Wernham, pp. 395–96.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gray, Randal (1978). "Spinola's Galleys in the Narrow Seas 1599–1603". The Mariner's Mirror. 64 (1): 69–75. doi:10.1080/00253359.1978.10659067.

- ^ a b c Kirsch, p. 63.

- ^ a b c . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b c d Churchill, Awnsham (2012). Collection of Voyages and Travels;. Lightning Source UK Ltd. p. 203. ISBN 978-1-231-02983-1.

- ^ a b Rodger, N.A.M. (17 November 1999). The Safeguard of the Sea. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-393-31960-6.

- ^ a b Loades, pp. 288–89

Bibliography

- Bicheno, Hugh. (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 978-1-84486-174-3.

- Graham, Winston (1976). The Spanish Armadas. Fontana. ISBN 978-0-88029-168-2.

- Guilmartin, John Francis (2002). Galleons and Galleys. Cassell. ISBN 978-0-304-35263-0.

- Kirsch, Peter (1990). Galleon: The Great Ships of the Armada Era. Naval Inst Pr. ISBN 978-1-55750-300-8.

- Lavery, Brian (2003). The Ship of the Line – Volume 1: The Development of the Battlefleet 1650–1850. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-252-3.

- Loades, David (2003). Elizabeth I. Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-304-4.

- Motley, John Lothrop (1888). History of the United Netherlands: From the Death of William the Silent to the Twelve Years' Truce. New York: Harper & brothers. OCLC 8903843.

- Nelson, Arthur (2001). The Tudor Navy: The Ships, Men and Organisation, 1485–1603. Conway Maritime Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85177-785-6.

- Wernham, R.B. (1994). The Return of the Armadas: The Last Years of the Elizabethan Wars Against Spain 1595–1603. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820443-5.