Second Battle of Newtonia

| Second Battle of Newtonia | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Field south of Newtonia, near the eastern edge of the fighting | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James G. Blunt | Joseph O. Shelby | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,500 or 2,000 | 2,000 or 3,500 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 26–400 | 24–275 | ||||||

The Second Battle of Newtonia was fought on October 28, 1864, near Newtonia, Missouri, between cavalry commanded by Major General James G. Blunt of the Union Army and Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby's rear guard of the Confederate Army of Missouri. In September 1864, Confederate Major General Sterling Price had entered the state of Missouri with hopes of creating a popular uprising against Union control of the state. A defeat at the Battle of Pilot Knob in late September and the strength of Union positions at Jefferson City led Price to abandon the main objectives of the campaign; instead he moved his force west towards Kansas City, where it was badly defeated at the Battle of Westport by Major General Samuel R. Curtis on October 23. Following a set of three defeats on October 25, Price's army halted to rest near Newtonia on October 28.

On the afternoon of the 28th, Union pursuers commanded by Blunt caught up with Price and drove back his skirmishers. Price ordered the withdrawal of his main army, and tasked Shelby with holding a rear guard. Shelby initially had a numerical advantage, and used it to outflank Blunt's shorter line. With his men low on ammunition, Blunt was considering a retreat shortly before sundown when reinforcements arrived in the form of Brigadier General John B. Sanborn and his brigade. Sanborn formed on Blunt's left, and the Union troops counterattacked. Shelby ordered a retreat, and the Union troops did not begin to pursue until October 30. Once the pursuit began, it continued until they reached the Arkansas River. The Confederates did not stop retreating until they reached Texas; Price had lost over two-thirds of his army during the campaign. Though both sides initially claimed victory, modern historians credit the Union with a victory at Newtonia. Estimates of casualties suffered during the battle range greatly.

Background

When the American Civil War began in 1861, the state of Missouri was a slave state, but did not secede. The state was politically divided: Governor Claiborne Fox Jackson and the Missouri State Guard (MSG) supported secession and the Confederate States of America, while Brigadier General Nathaniel Lyon and the Union Army supported the United States and opposed secession.[1] Under Major General Sterling Price, the MSG won several victories over the Union Army in 1861, but by the end of the year, Price and his men were restricted to the southwestern portion of the state. Meanwhile, Jackson and a portion of the state legislature voted to secede and join the Confederacy, while another element of the legislature voted to reject secession, giving the state two competing governments.[2] In March 1862, a Confederate defeat at the Battle of Pea Ridge in Arkansas gave the Union control of Missouri,[3] and Confederate activity in the state was largely restricted to guerrilla warfare and raids throughout 1862 and 1863.[4]

By the beginning of September 1864, events in the eastern United States, especially the Confederate defeat in the Atlanta campaign, gave Abraham Lincoln an advantage in the 1864 United States presidential election. Lincoln supported continuing the war, while his opponent, George B. McClellan, favored ending the conflict. At this point, the Confederacy had very little chance of winning.[5] As events east of the Mississippi River turned against the Confederates, General Edmund Kirby Smith, Confederate commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, was ordered to transfer the infantry under his command to the fighting in the Eastern and Western Theaters. This proved impossible, as the Union Navy controlled the Mississippi River, preventing a large-scale crossing.[6]

Despite having limited resources for an offensive, Smith decided that an attack designed to divert Union troops from the principal theaters of combat would have an equivalent effect as the proposed transfer of troops, through decreasing the Confederates' numerical disparity east of the Mississippi. Price and the Confederate Governor of Missouri Thomas Caute Reynolds suggested that an invasion of Missouri would be an effective offensive; Smith approved the plan and appointed Price to command the offensive. Price expected that the offensive would create a popular uprising against Union control of Missouri, divert Union troops away from principal theaters of combat (many of the Union troops previously defending Missouri had been transferred out of the state, leaving the Missouri State Militia as the state's primary defensive force), and aid McClellan's chance of defeating Lincoln in the election.[6] On September 19, Price entered the state from Arkansas with the Army of Missouri.[7]

Originally, Price and his army had hoped to capture St. Louis, but a defeat at the Battle of Pilot Knob in late September dissuaded the Confederates from assaulting that city. Jefferson City, a secondary target, was deemed too strong to attack when it was reached in early October, so the Confederates began moving westwards towards Kansas City. Major General William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Union Department of the Missouri, began mobilizing troops against Price. On October 23, Union Major General Samuel R. Curtis and the Army of the Border caught up with Price near Kansas City and badly defeated him in the Battle of Westport. The Army of Missouri then began retreating through Kansas, and was defeated three times on October 25, including the Battle of Mine Creek, which was a disastrous rout in which large quantities of supplies and soldiers were captured.[8]

The Confederates were able to get an eight-hour lead over the Union troops, although the pursuers soon narrowed the gap to two-and-a-half hours by the afternoon of the 26th. Union troops reported finding Confederate stragglers dying of starvation during the retreat, and Price lost many men to desertion. Claims of the execution of prisoners were made against both armies.[9] On October 28, Price halted his retreat near Newtonia, Missouri, (the site of the 1862 First Battle of Newtonia) hoping to give his weary men a rest.[8] Grain could be obtained in the Newtonia area, while Price's path of retreat would soon go through a relatively barren part of Arkansas.[10] A small Union outpost was located in the town. Confederate soldiers who were Newtonia locals were aware of the outpost, and two detachments were sent to drive out the Union defenders. The flat prairie terrain around Newtonia precluded any element of surprise, and the defenders fled the town. One Union soldier, Lieutenant Robert H. Christian, was captured, killed (possibly after surrendering), and mutilated.[11][12]

Battle

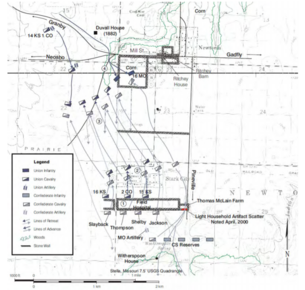

Price's men encamped south of Newtonia, in some woods near the McClain Farm.[13][14] Some of the soldiers were sent into town to bring a flour mill into use. A report of approaching Union soldiers reached the Confederate camp, and Brigadier General M. Jeff Thompson attempted to organize a group of soldiers of his brigade to meet the threat.[15] Thompson was unable to convince many of the tired Confederates to break their rest, and was only able to get about 200 men to follow him. When no Union soldiers arrived and straggling Confederate soldiers arrived to dispute the rumor, Thompson sent his men back to the camp.[15][16] At around 14:00, Union soldiers under the command of Colonel James H. Ford arrived,[14] having approached the battlefield from the northwest.[13] Ford deployed McLain's Colorado Battery and the 2nd Colorado and 16th Kansas Cavalry Regiments.[17] The Confederates were harvesting corn when the Union troops arrived and their skirmishers were quickly driven away from their position west of the town near the Mathew H. Ritchey Farm.[13][18] While this action was occurring, Union Major General James G. Blunt arrived to take command of the action;[17] he personally fought with the 16th Kansas Cavalry during this stage of the fighting.[19]

Price was caught by surprise;[20] he ordered Brigadier General Joseph O. Shelby to provide a rear guard while the rest of his army withdrew, as he believed that Curtis and the entire Union army was attacking him.[18] This movement prevented Price from sending any reinforcements to Shelby during the ensuing battle, even though they would be requested; Shelby's command was the only effective force left in the Confederate army anyway.[21] An element of Major General James F. Fagan's division had previously reported the approach of Union troops, but this report had been dismissed by Fagan.[22] Meanwhile, Blunt made two incorrect assumptions: that Curtis was close behind his force in support, and that the Confederates would not act aggressively.[20] As a result, Blunt decided to attack with his two brigades, which numbered only about 1,000 men;[18] the brigades were nominally under the command of Colonel Charles R. Jennison and Ford, although Lieutenant Colonel George H. Hoyt held temporary command of the former unit as Jennison was sick.[20][23] Hoyt's unit had arrived on the field not long after Ford's, having been close enough behind the leading unit that it was forced to ride through the dust cloud formed by Ford's movement.[17]

The Union troopers then moved up to the northern edge of the McClain Farm with four cavalry regiments in a line from left to right in the order of the 16th Kansas Cavalry, the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry Regiment, the 2nd Colorado Cavalry, and the 15th Kansas Cavalry Regiment; McLain's Battery formed up in a supporting position with four Parrott rifles.[24][25] Shelby deployed his men 500 yards (460 m) away on the other side of the farm, with the brigades of Thompson and Colonel Sidney D. Jackman in the center and two small mounted detachments covering the flanks.[24] Slayback's Missouri Cavalry Battalion and the 5th Missouri Regiment were positioned between Thompson's main body and the mounted group on the Confederate left.[26] The two guns of Collins's Missouri Battery provided artillery support; and was in turn supported by Nichols's Missouri Cavalry Regiment and Hunter's Missouri Cavalry Regiment.[27] The modern historian Charles D. Collins Jr. estimates that Shelby's division fielded about 1,500 to 2,000 men at Newtonia,[24] while the historian Mark A. Lause states that no more than 3,500 to 4,000 Confederates would have fought in the battle.[28] The two sides' artillery opened fire, Collins's Battery having the early advantage over McLain, whose pieces had trouble finding the range of the Confederates.[29] The distance between the two units was great enough that small arms fire was not attempted in large-scale, and what was shot had essentially no effect.[19][30] Either two[29] or four[31] mountain howitzers were added to the Union line by Hoyt; they were more effective than McLain's pieces, but could not gain an advantage over Collins. Fearing that the Union guns' numerical advantage would eventually overwhelm Collins,[29] Shelby ordered an attack, which outflanked the Union line and had initial success.[18] The Union soldiers fell back about 200 yards (180 m).[25] Only Thompson's brigade participated in the attack, as Jackman's men were left behind to support Collins's battery.[21] Colonel Moses W. Smith, commander of the 11th Missouri Cavalry Regiment, suffered a mortal wound during the charge.[21][32]

While the two mountain howitzers helped hold the Union right against Confederate threats,[32] the mounted detachment on the Confederate right outflanked the Union left, causing the retreat of McLain's Battery. Blunt had ordered an orderly retreat of about 300 yards (270 m),[31] but the sight of the guns retreating demoralized some of the men of the 15th and 16th Kansas Cavalry Regiments, parts of which were routed. Watching elements of their opponents flee emboldened the Confederates, and the attack was pressed harder. The Union lines fell back all the way to the Ritchey Farm, where they reformed their lines,[33] a process which was aided by the redeployment of McLain's battery.[34] Even after this line was formed, some of the Union troops were still heading for the rear.[31] A charge by two companies of the 2nd Colorado Cavalry surprised the Confederates and temporarily threw them into disorder.[32] Confederate troops were also threatening to turn the Union left.[35] Blunt, concerned that his men would run out of ammunition, began making preparations to withdraw from the field and positioned McLain's Battery on an elevation behind his main line.[33] By now, it was approaching sundown, and Union reinforcements commanded by Brigadier General John B. Sanborn arrived on the field at around 17:00, having made a forced march from Fort Scott, Kansas after receiving orders from Curtis to join Blunt earlier in the day. After arriving, Sanborn formed his men to Blunt's left;[18][36] there were now about 1,500 or 2,000 Union soldiers in the fight.[28][37]

Curtis arrived with Sanborn, and watched McLain's Battery withdraw in a state that Curtis described as "badly cut up".[38] He helped to rally the Colorado battery, while Sanborn dismounted his men and prepared for an assault. Once Sanborn's men began attacking, Blunt's rejuvenated troopers joined in the counterattack. Two Rodman guns of Battery H, 2nd Missouri Light Artillery Regiment had arrived, giving the Union an artillery advantage of eight guns to two.[38][39][40] These newly arrived guns fired 22 shots during the battle.[35] With the Union having thrown fresh troops into the fray and with the artillery advantage growing more marked, Shelby ordered a withdrawal.[38][39] The Union counterattack drove for about 1 mile (1.6 km) before halting.[40] Elements of Fagan's command arrived to reinforce Shelby during the retreat, but the Confederates still withdrew to some woods near their original camp.[38] Lause believes that part of Brigadier General John S. Marmaduke's Confederate division also participated in the battle.[32] By this time, both sides were heavily fatigued, and Curtis and Blunt decided to postpone any pursuit until morning.[38] Ford's and Hoyt's men left the battlefield at about 21:00,[40] after which they occupied the town.[28]

Aftermath and preservation

Both armies claimed victory. Curtis reported that the Confederates had been "conquered", while Price claimed that Blunt had been driven back 3 miles (5 km) and to have inflicted severe casualties.[38] Shelby's chief of staff, John Newman Edwards, stated that "another beautiful victory had crowned the Confederate arms".[41] Both the American Battlefield Trust and the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission interpret the outcome as a Union victory.[42][43] Likewise, estimates of casualties vary greatly. A contemporary newspaper reported 113 Union casualties, and under 200 for the Confederates.[38] The modern historian Albert E. Castel places total Confederate casualties at 24 and those for the Union at 26,[18] while the modern historian Kyle Sinisi places Union losses at 114 and estimates that Confederate losses were probably similar or less than those of the Union.[44] Lause states that Blunt reported Union losses as 118 killed and wounded and that Union officer Richard J. Hinton provided a figure of 114 Union casualties. Higher figures for Confederate losses are given by Lause, who reports that the Confederates "supposedly" lost about 275 men. The frequently unreliable Edwards later stated that the Confederates lost about 800 men at Newtonia.[28] The American Battlefield Trust estimates 250 and 400, respectively.[42] It is known that 46 wounded Confederates were captured by Union troops when they were abandoned after the battle due to Price's army's inability to transport them. The Ritchey and McLain houses were both used as field hospitals, as was the Witherspoon house, which was southwest of the McLain farm.[44] Both contemporary and postwar writers either praised Blunt for playing a decisive role in the victory or criticized his decision to attack with a small force as reckless.[45]

During the night after the battle, most of Shelby's men left the field to rejoin Price's main command, having completed their mission of providing a rear guard.[18] The Confederate 12th Missouri Cavalry Regiment was left on the field until morning as an observation force.[46] Sanborn's men spent the night east of Newtonia, while the other two Union brigades fell back to the northwest of the town.[40] Price's army, which Castel described as being essentially an armed mob after the October 25 Battle of Marmiton River, began falling completely apart.[18][47] Rosecrans had received orders from General Ulysses S. Grant to divert any troops not needed to deal with Price east of the Mississippi, so two brigades, including Sanborn's, were detached from Curtis on October 29. Curtis planned on stopping the pursuit, but the detached troops were returned to him the next day, and the pursuit resumed.[48] Price withdrew to the Arkansas River via Cane Hill, Arkansas; Curtis's pursuit ended on November 8, at the Arkansas River. After marching through the Indian Territory, the Confederates reached Texas. The campaign had cost Price more than two-thirds of the men he had taken into Missouri.[18]

The battlefield was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Second Battle of Newtonia Site on December 23, 2004.[49] Within the historic district are four contributing properties: the battlefield proper, the position of McLain's Battery on the ridge, a cornfield at the site of the Ritchey Farm, and the site of a historic road that led to Granby.[50] Most of the areas where fighting occurred are preserved in the district, which shares a boundary with the First Battle of Newtonia Historic District at two places.[51] Modern landscape use is similar to that in 1864, although railroad construction and open-pit mining have intruded on the site.[52] The American Battlefield Trust has been involved in the preservation of 8 acres (3.2 ha) at Newtonia.[53]

The Ritchey House and 25 acres of the battlefields including the Old Newtonia Cemetery were added to Wilson's Creek National Battlefield in 2022 by the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, despite National Park Service opposition due to the lack of connection, need for protection, or enhancement of public enjoyment.[54][55]

References

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 20–25.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 34–37.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 377–379.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 343.

- ^ a b Collins 2016, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Collins 2016, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1998, pp. 134, 380–386.

- ^ Lause 2016, pp. 173–174.

- ^ Lause 2016, p. 175.

- ^ Wood 2010, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Collins 2016, p. 172.

- ^ a b Wood 2010, p. 118.

- ^ a b Wood 2010, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, p. 316.

- ^ a b c Wood 2010, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Castel 1998, p. 386.

- ^ a b Sinisi 2020, p. 318.

- ^ a b c Collins 2016, p. 173.

- ^ a b c Wood 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, p. 314.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, p. 317.

- ^ a b c Collins 2016, pp. 174–175.

- ^ a b Sinisi 2020, p. 319.

- ^ Wood 2010, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, p. 315.

- ^ a b c d Lause 2016, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Collins 2016, p. 175.

- ^ Wood 2010, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Sinisi 2020, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d Lause 2016, p. 177.

- ^ a b Collins 2016, p. 177.

- ^ Wood 2010, p. 125.

- ^ a b Wood 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Sinisi 2020, pp. 317, 321.

- ^ Collins 2016, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d e f g Collins 2016, p. 179.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2013, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Sinisi 2020, p. 321.

- ^ Wood 2010, p. 129.

- ^ a b "Second Battle of Newtonia". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "Technical Volume II: Battle Summaries" (PDF). Civil War Sites Advisory Commission. 1998. p. 82. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ a b Sinisi 2020, p. 322.

- ^ Wood 2010, p. 131.

- ^ Wood 2010, p. 130.

- ^ Castel 1993, p. 245.

- ^ Collins 2016, p. 181.

- ^ "National Register Database and Research". National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 28, 2018. Retrieved September 18, 2020.

- ^ Stith & Maserang 2004, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Stith & Maserang 2004, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Stith & Maserang 2004, pp. 8, 25.

- ^ "Newtonia Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ "S. Rept. 117-185 - Wilson's Creek National Battlefield Addition". Congress.gov. October 18, 2022.

- ^ Ostmeyer, Andy (October 15, 2021). "Fight to preserve Newtonia continues, but with new sense of urgency". Joplin Globe. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

Sources

- Castel, Albert (1993) [1968]. General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West (Louisiana Paperback ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1854-0.

- Castel, Albert (1998). "Newtonia II, Missouri". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Collins, Charles D. Jr. (2016). Battlefield Atlas of Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (PDF). Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-940804-27-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Lause, Mark A. (2016). The Collapse of Price's Raid: The Beginning of the End in Civil War Missouri. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-826-22025-7.

- "Newtonia Battlefields Special Resource Study" (PDF). National Park Service. 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- Sinisi, Kyle S. (2020) [2015]. The Last Hurrah: Sterling Price's Missouri Expedition of 1864 (paperback ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-4151-9.

- Stith, Matthew M.; Maserang, Roger (April 2004). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Second Battle of Newtonia Site" (PDF). Missouri Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved September 19, 2020.

- Wood, Larry (2010). The Two Civil War Battles of Newtonia. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-59629-857-6.