Capture of New Orleans

| Capture of New Orleans | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

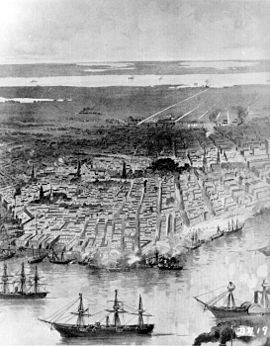

Panoramic view of New Orleans; federal fleet at anchor in the river (c. 1862) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

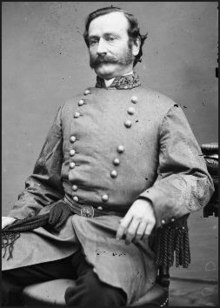

David Farragut Benjamin Butler | Mansfield Lovell | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Department of the Gulf West Gulf Blockading Squadron | Department No. 1 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| None | None | ||||||

The capture of New Orleans (April 25 – May 1, 1862) during the American Civil War was a turning point in the war that precipitated the capture of the Mississippi River. Having fought past Forts Jackson and St. Philip, the Union was unopposed in its capture of the city itself.

Many residents resented the controversial and confrontational administration of the city by its U.S. Army military governor. This capture of the largest Confederate city was a major turning point and an event of international importance. It also caught many Confederate generals by surprise who had planned for an attack from the north instead of from the Gulf of Mexico.[3]

Background

The history of New Orleans differs significantly with the histories of other cities that were included in the Confederate States of America. Because it was founded by the French and controlled by Spain for a time, New Orleans had a population who were mostly Catholic and had created a more cosmopolitan culture than in some of the Protestant-dominated states of the British colonies. Its population was highly diverse. At the time of the Civil War, much of the population was made up of French-speaking Creoles, refugees from Saint Domingue and the Haitian Revolution, enslaved and free Blacks of African and mixed descent, and recent Irish and German immigrants.[4]

New Orleans had benefited more than some other cities by the domestic slave trade, Industrial Revolution, international trade, and geographical position. It was a major port near the mouth of the Mississippi River at the Gulf Coast. The river carried freight and traffic from a huge network of rivers and tributaries, making New Orleans one of the most significant transportation centers in the early United States before the establishment of railroad and road systems. Of particular significance were the inventions of the cotton gin in 1793 and steamboat in the early 19th century.[5]: 10–11, 214

Before the steamboat, keelboat men bringing cargo downriver would break up their boats for lumber in New Orleans and travel overland back to Kentucky, Tennessee, Ohio, or Illinois to repeat the process. Steamboats had enough power to move upstream against the strong current of the Mississippi, making two-way trade possible between New Orleans and the cities in the interior river network of the Upper South and Midwest. After the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, which greatly expanded international trade, and the development of the cotton gin, cotton became a valuable export product. It became a major part of the volume of cargo moved through the city.[5]: 10–11, 214

Jacksonian democracy and manifest destiny

A formative event in the early history of New Orleans was the 1815 Battle of New Orleans. Fought during the War of 1812, the battle's American victory led by General Andrew Jackson enhanced his political career. Along with Martin Van Buren, he founded the Democratic Party. Jackson began a new political movement now known as the Jacksonian democracy.

This new direction in American politics had a profound influence on the development of New Orleans and the American Southwest. One of these developments was the construction of Fort Jackson, Louisiana, a star fort suggested by and named after Jackson. This fortress was intended to support Fort St. Philip and bar the Mississippi Delta from invasion.[6]

The presidents of the Jacksonian democracy supported the concept of manifest destiny, greatly expanding acquisition of territory in the American Southwest and the support of international trade, along with the expansion of slavery. This powerful political movement also produced sectional tension between the northern and southern portions of the United States, resulting in the creation of the Whig Party to oppose the new Democratic Party. As the political rivalry between the Jacksonian Democrats and the Whigs intensified, the Republican Party was founded, to counter the spread of slavery into states produced by territorial conquests of the Jacksonian Democrats. The victory of Abraham Lincoln, the Republican presidential candidate, in the election of 1860, resulted in the secession crisis and was a catalyst to the American Civil War.[6]

By the year 1860, New Orleans was in a position of unprecedented economic, military, and political power. The Mexican–American War, along with the annexation of Texas, had made New Orleans even more of a springboard for expansion. The California Gold Rush contributed another share to local wealth. The electrical telegraph arrived in New Orleans in 1848, and the completion of the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad from New Orleans to Canton, Mississippi, a distance of over 200 miles (320 km), added another dimension to local transportation.

The combination of all these factors resulted in an increase in the price of prime field hands of 21 per cent in 1848, and further increases as the value of the domestic slave trade grew through the 1850s. By 1860, New Orleans was one of the greatest ports in the world, with 33 different steamship lines and trade worth 500 million dollars passing through the city. As far as population, the city outnumbered any other city in the South, and was larger than the four next-largest Southern cities combined, with an estimated population of 168,675.[8][9]: 41 [10]: 353

War and battle

The election of Lincoln in 1860 inspired governor Thomas Overton Moore to interdict an effort to make New Orleans a “free city”, or neutral area in the conflict. A solid Democrat, Moore organized a movement that voted Louisiana out of the Union in a secession convention that represented only 5 percent of the citizens of Louisiana. Moore also ordered the Louisiana militia to seize the Federal arsenal at Baton Rouge, and the Federal forts (Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip that blocked approach upriver to New Orleans, Fort Pike that guarded the entrance to Lake Pontchartrain, the New Orleans Barracks south of the city, and Fort Macomb, which guarded the Chef Menteur Pass). These military moves were ordered on January 8, 1861, before the secession convention. With military companies forming all over Louisiana, the convention voted Louisiana out of the Union 113 to 17. The outbreak of hostilities in the area of Fort Sumter, South Carolina, led to the story of New Orleans in the Civil War.[11]

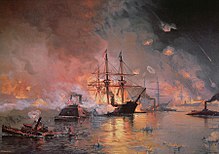

The Union's strategy was devised by Winfield Scott, whose "Anaconda Plan" called for the division of the Confederacy by seizing control of the Mississippi River. One of the first steps in such operations was the imposition of the Union blockade. After the blockade was established, a Confederate naval counterattack attempted to drive off the Union navy, resulting in the Battle of the Head of Passes. The Union countermove was to enter the mouth of the Mississippi River, ascend to New Orleans and capture the city, closing off the mouth of the Mississippi to Confederate shipping both from the Gulf and from Mississippi River ports still used by Confederate vessels. In mid-January 1862, Flag Officer David G. Farragut had undertaken this enterprise with his West Gulf Blockading Squadron. The way was soon open except the water passage past the two masonry forts held by Confederate artillery, Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip, which were above the Head of Passes approximately 70 miles (110 km) downriver below New Orleans.

From April 18 to 28, Farragut bombarded and then fought his way past these forts in the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip, managing to get thirteen of his fleet's ships upriver on April 24. Historian Allan Nevins argues the Confederate defenses were defective:

- Confederate leaders had made a tardy, ill-coordinated effort to muster at the river barrier. Fortunately for the Union, both the naval and military auxiliaries were weak. In all their work of defense, the Southerners had been hampered by poverty, disorganization, lack of skilled engineers and craftsmen, friction between State authorities and Richmond, and want of foresight.[12]

Major General Mansfield Lovell, Commander of Department 1, Louisiana, was left with one tenable option after the Union Navy broke through the Confederate ring of fortifications and defense vessels guarding the lower Mississippi: evacuation. The inner ring of fortifications at Chalmette was intended only to resist ground troops and few of the gun batteries were aimed toward the river. Most of the artillery, ammunition, troops, and vessels in the area were committed to the Jackson/St. Phillips position. Once this defense was breached, only three thousand militiamen with sundry military supplies and armed with shotguns remained to face Union troops and warships. The city itself was a poor position to defend against a hostile fleet. With high water outside the levees, Union ships were elevated above the city and able to fire down into the streets and buildings below. Besides the ever-present danger of weather-caused breaks in the levees, now an even greater threat to New Orleans was the ability of the Union military to cause a break in a major levee that would lead to flooding most of the city, possibly destroying it within a day.[13]

Lovell loaded his troops and supplies aboard the New Orleans, Jackson, and Great Northern railroad and sent them to Camp Moore, 78 miles (126 km) north. All artillery and munitions were sent to Vicksburg. Lovell then sent the last message to the War Department in Richmond, “The enemy has passed the forts. It is too late to send any guns here; they had better go to Vicksburg.” Military stores, ships, and warehouses were then burned. Anything considered useful to the Union, including thousands of bales of cotton, were thrown into the river.[14]

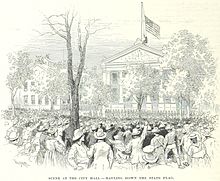

Despite the complete vulnerability of the city, the citizens along with military and civil authorities remained defiant. At 2:00 p.m. on April 25, Admiral Farragut sent Captain Bailey, First Division Commander from the USS Cayuga, to accept the surrender of the city. Armed mobs within the city defied the Union officers and marines sent to city hall. General Lovell and Mayor Monroe refused to surrender the city. William B. Mumford pulled down a Union flag raised over the former U.S. mint by marines of the USS Pensacola and the mob destroyed it. Farragut did not destroy the city in response but moved upriver to subdue fortifications north of the city. On April 29, Farragut and 250 marines from the USS Hartford removed the Louisiana State flag from the City Hall.[15] By May 2, U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward declared New Orleans "recovered" and "mails are allowed to pass".[16]

Occupation and pacification

On May 1, 1862, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler occupied the city of New Orleans with an army of 5,000, facing no resistance. Butler was a former Democratic party official, lawyer, and state legislator. He was one of the first Major Generals of Volunteers of the Civil War appointed by Abraham Lincoln. He had gained glory as a Massachusetts state militia general who had anticipated the war and carefully prepared his six militia regiments for the conflict. At the start of hostilities he immediately marched to the relief of Washington, D.C., and, despite a lack of orders, had occupied and restored order to Baltimore, Maryland. As a reward Butler was made commander of Fortress Monroe, on the Virginia Peninsula. There he gained further political renown as the first to confiscate "fugitive slaves" as contraband of war. This practice was later made a policy of war by Congress. Due to these and other astute political maneuvers, Butler had been chosen to command the army expedition to New Orleans. Because of his lack of military experience and military success, many were happy to see him go.[17]: 23–26

Challenge of occupation

The United States War Department under Edwin M. Stanton expected Butler to hold eastern Louisiana and the cities of Baton Rouge and New Orleans, maintain communications up river to Vicksburg, and support Farragut's forces for the siege of Vicksburg. In addition, the city of New Orleans itself was just as indefensible for the Union as for the Confederates. Surrounded by a fragile network of levees and lower in elevation than the river around it, New Orleans was extremely vulnerable to flooding, bombardment, and insurrection. In addition, the city was generally unhealthy and subject to devastating epidemics. Defense of the city against attacks from Confederate forces depended on an extensive outer ring of fortifications requiring a garrison of thousands of troops. As a conquered territory, Louisiana had a potential for becoming a serious logistical drain on Union forces, and an unsustainable front if contested by well-organized resistance movements. It was popularly assumed that the Confederacy would launch a major counteroffensive to retake New Orleans. As the largest population center of the Confederacy, and commanding formidable industrial and shipping resources, its permanent loss would be politically intolerable to the Confederacy.[18]

Butler's command of the city

Butler was one of the most controversial and volatile personalities of the Civil War. He became infamous in New Orleans for his confrontational proclamations and for alleged corruption. The impression had been created by Confederate officials and sympathizers[19] that New Orleans and Louisiana were held by brute military force and terror. Butler was a political general, awarded his position by political connections and this political background made his position in New Orleans tenable until outrage forced his withdrawal in 1862. Butler faced a difficult challenge securing the Confederacy's largest city with a relatively small force. His total military command numbered 15,000 troops. He was not sent reinforcements during the time he commanded in Louisiana, between May and December 1862. Butler stated, "We were 2,500 men in a city... of 150,000 inhabitants, all hostile, bitter, defiant, explosive, standing literally in a magazine, a spark only needed for destruction." His methods of preserving order were seen as radical and totalitarian even in the North and Europe, .[20]: 108–109

Butler's General Order No. 28

The residents of New Orleans, and notably many women, did not accept the Union occupation very well. Butler's troops faced "all manner of verbal and physically symbolic insults" from women, including obvious physical avoidance such as crossing the street or leaving a streetcar to avoid a Union soldier, being spat upon, and having chamber pots being dumped upon them.[21] The Union troops were offended by the treatment, and after two weeks of occupation, Butler had had enough. He issued his General Order No. 28, which instructed Union soldiers to treat any woman who offended a soldier "as a woman of the town plying her avocation".

HDQRS. DEPARTMENT OF THE GULF

- New Orleans, May 15, 1862.

- As the officers and soldiers of the United States have been subject to repeated insults from the women (calling themselves ladies) of New Orleans in return for the most scrupulous non-interference and courtesy on our part, it is ordered that hereafter when any female shall by word, gesture, or movement insult or show contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States she shall be regarded and held liable to be treated as a woman of the town plying her avocation.

- By command of Major-General Butler:

- GEO. C. STRONG,

- Assistant Adjutant-General and Chief of Staff.[22][23]

The reaction to Butler's General Order No. 28 was swift and the outrage against it highly vocal. Southern women were highly offended by the order. He was heavily criticized both domestically and overseas, which was a problem as the Union sought to avoid European intervention in the war on the behalf of the Confederacy. Butler became known as "The Beast."[24] The British House of Lords called it a "most heinous proclamation" and regarded it as "one of the grossest, most brutal, and must unmanly insults to every woman in New Orleans." The Earl of Carnarvon proclaimed the imprisonment of women a "more intolerable tyranny than any civilized country in our day [has] been subjected to."[25] The Saturday Review criticized Butler's rule, accusing him of "gratifying his own revenge" and likening him to an uncivilized dictator:

If he had possessed any of the honourable feeling which is usually associated with a soldier's profession, he would not have made war on women. If he had even been endowed with the ordinary magnanimity of a Red Indian, his revenge would have been satiated before now. It required not only the nature of a savage, but of a very mean and pitiful kind of savage, to be induced by indignation at a woman's smile to inflict an imprisonment so degrading in its character as that which seems to constitute his favourite punishment, and accompanied by privations so cruel.... It is only a pity that so unadulterated a barbarian should have got hold of an Anglo-Saxon name.[26]

Butler tried to defend his command in New Orleans in a letter to the Boston Journal, claiming "the devil had entered the hearts of the women of [New Orleans]... to stir up strife" and falsely claimed that the order had been very effective. He said, in essence, the effective way to deal with a Confederate-sympathizing woman who is defiant was to be treat her as one would an undignified prostitute, that is to ignore her.[27] But many thought the language of the order was too ambiguous and feared that Union troops would treat New Orleans women like prostitutes in regards to soliciting them for sex and perhaps even rape.[28] Butler's inflammatory order was so controversial that it caused a significant public relations problem for the Union and he was withdrawn from New Orleans in December 1862, just eight months after taking command of the city.

Building a political power base in New Orleans

The most valuable asset Butler commanded in New Orleans was not his army but his formidable political heritage. Butler was a Jacksonian Democrat in all senses, and a populist and reformer. He had a great gift for identifying with the issues of the broadest levels of the voters, and turning them to his political advantage. Here the Jacksonian political legacy had come full circle in 47 years, from defending New Orleans from the British, to securing it from secession. Butler's inscription on the base of Jackson's statue, “The Union Must and Shall be Preserved,” was symbolic of his political identity. The inscription echoed Andrew Jackson's 1830 toast in response to a speech endorsing "nullification," during what was called the Nullification Crisis. Jackson stated, "Our Federal Union! It must be preserved!" That statement defined Jackson's position against any threat to the Union.[29]

The spoils system created by the Democratic Party was also part of Butler's political heritage. Butler believed the advantages of political office should be used to the advantage of friends and supporters, and to suppress political opponents. In general, Butler used these political abilities to play the various factions and interests in New Orleans, as a virtuoso conductor would inspire an orchestra, to ensure his control and reward Union supporters while isolating and marginalizing hostile pro-Confederate factions.[30]

The poorer classes as the key to the city

Butler began his rule of martial law in New Orleans by sentencing anyone calling for cheers for Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Confederate Major General P. G. T. Beauregard to three months hard labor at Fort Jackson. He also issued Order Number 25, which distributed captured Confederate food supplies of beef and sugar in the city to the poor and starving. The Union blockade and the King Cotton embargo had done damage to the port economy, leaving many without work. The value of goods passing through New Orleans had gone from $500 million to $52 million during the period 1860 to 1862.[31]

Butler raised three regiments of infantry, the 1st and, 2nd on September 27,[32] and a 3rd by November, from existing free black militia units. This Corps D'Afrique, with a total of 3,122 soldiers and officer, was supervised by Gen. Daniel Ullmann and were unusual in having black officers. They served both to add to his forces and to confront the former ruling classes of the city with the bayonets of those they had formerly enslaved. Butler also used his commercial contacts in the northeast and Washington to revive commerce in the city, exporting 17,000 bales of cotton to the northeast and re-establishing international trade. He employed many local citizens in logistics support of the Union military and in cleaning up the city, including an expansion of the existing city sewer system and setting up pumps to empty the system into the river. This policy helped free the city from the anticipated summer yellow fever epidemic, possibly saving thousands of lives. He extensively taxed the wealthy of the city to set up social programs for the lower classes. These "Robin Hood" aspects of his programs provided a broad base of political support, an extensive informal intelligence and counter-espionage organization, and provided law and order.[33][34]

Impact of the occupation on enslaved people and slavery

Butler had already done the institution of slavery in the Confederacy considerable damage by instituting his "contraband of war" policy while commanding Fort Monroe on the Virginia peninsula. This policy rationalized the retention of enslaved people fleeing the seceding states by claiming that the Confederate military was using slave labor for military use in the construction of fortifications, moving military supplies, and constructing roads and railroad grades of use to the Confederate army. Enslaved people within areas of Confederate control rapidly spread the word that Union military forces were not enforcing the fugitive slave laws, and that those fleeing slavery could find refuge within Union military lines and employment as laborers for the Union armies. As a result, the Confederacy avoided employing enslaved people in proximity of Union forces as the enslaved would flee at first opportunity to Union lines, depriving the Confederate armies of their labor and their former masters of what they regarded as their valuable property. Since the Confederate government was counting on slave labor to offset the greater numbers of Union soldiers, Butler's innovative policy struck the Confederacy at a strategic level, destroying an asset counted on to win the war.[35]

The flight of enslaved people toward the Union also diverted the resources of the Confederate military and its government to the defense of the plantations. The planters of Louisiana, afraid the laborers they enslaved would revolt, appealed for aid from Union authorities. "Our family has owned negroes for generations," wrote one "we have no one but yourself and Genls Shepley and Butler to protect us against these negroes in a state of insurrection." The plantations of Jefferson Davis, located in the state of Mississippi on Davis Bend 20 miles (32 km) downriver from Vicksburg, were also disrupted by the Union invasion. After Davis' older brother Joseph fled the area with some of his enslaved laborers in May 1862, the rest revolted, took possession of the property, and betrayed the location of valuables to Union forces, resisting any efforts by Confederate forces to recapture the area. The rebelling laborers armed themselves with guns and newspapers[clarification needed], and fought to the death any attempts to infringe upon their newfound freedom. This rebellion within a rebellion began to erode Confederate authority within Louisiana the instant Butler's troops appeared in New Orleans and, as a political fifth column, was invaluable to his occupation.[35]

The Confederate counterstroke

The expected rebel counteroffensive came on August 5 in the form of a naval and army assault on Baton Rouge, led by Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge, resulting in the Battle of Baton Rouge. After a hard-fought battle, the Confederate forces were driven out of the city, and both Confederate and Union forces withdrew after the battle. The significant aspect of the battle was that it did not result in a popular uprising or widespread support for Confederate forces in Louisiana. As a result, Rebel forces were not able to mount a sustained campaign to retake New Orleans or the rest of the state. This can be considered a tribute to the Union consensus building wrought by Butler's political manipulation and broad-based political support. Chester G. Hearn summed up the basis of this support: “The huge, illiterate majority – the poorer classes of blacks and whites – would have starved had Butler not fed and employed them, and thousands may have died had his sanitation policies not cleansed the city of disease.”[36]

Reputation vs. results

Butler's generally abrasive style and heavy handed actions, however, caught up with him. Many of his acts gave great offense, such as the seizure of $800,000 that had been deposited in the office of the Dutch consul and his imprisonment of the French champagne magnate Charles Heidsieck. Most notorious was Butler's General Order No. 28 of May 15, issued after many provocations and displays of contempt by women in New Orleans. It stated that if any woman insulted or showed contempt for any officer or soldier of the United States, she would be regarded and shall be held liable to be treated as a "woman of the town plying her avocation," a prostitute. The order provoked protests both in the North, the South and abroad, particularly in Britain and France, and many considered it the cause of his removal from command of the Department of the Gulf on December 17, 1862. He was also nicknamed "Beast Butler" and "Spoons" for his alleged habit of pilfering the silverware of Southern homes in which he stayed. He became so reviled in the city that merchants began selling chamber pots with his likeness at the bottom.[citation needed]

On June 7, he executed William B. Mumford, who had torn down a U.S. flag placed by Farragut on the New Orleans Mint. For the execution, Butler was denounced in December 1862 by Confederate President Jefferson Davis in General Order 111 as a felon deserving capital punishment, who, if captured, should be reserved for execution. Butler's administration did have benefits to the city, which was kept both orderly and healthy. The Butler occupation was likely best summed up by Admiral Farragut, who stated, "They may say what they please about General Butler, but he was the right man in the right place in New Orleans."[36]

Aftermath

On December 14, 1862, Maj. Gen. Nathaniel Banks arrived to take command of the Department of the Gulf. Butler was not made aware of the change until Banks arrived to tell him. Contrary to common belief, Butler's inflammatory reign had little to do with his replacement. Political considerations in Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio tipped the balance. The Democratic victories in Illinois and Ohio on November 4 had alarmed the Lincoln administration.

Those new considerations reinforced the idea by Secretary of State William H. Seward, one of Butler's political opponents, that an invasion of Texas would be favorably received by a pro-union group of German American cotton farmers living there. The idea was championed by Banks, a New England political general eager to send cotton to mills in the Northeast. Banks undertook the siege of Port Hudson and, after its successful conclusion, began the Red River Campaign in pursuit of Texan cotton. The Red River expedition proved to be a costly failure and resulted in more wanton destruction and looting than the Butler occupation.[37]: 10–28

See also

Notes

- ^ Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. I, v. 18, p. 131.

- ^ Atlas to accompany the official records of the Union and Confederate armies. Plate XC.

- ^ "Union captures New Orleans". www.History.com. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ Fredrick Mar Spletstoser, “The Impact of the Immigrants on New Orleans,” in The Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial Series in Louisiana History, vol. X: A Refuge for All Ages: Immigration in Louisiana History, ed. Carl A. Brasseaux (Lafayette, 1996), 287–322; Campanella, Geographies of New Orleans, 224; Earl F. Niehaus, “The New Irish, 1830–1862,” in Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial Series in Louisiana History, X, ed. Brasseaux, 378–391.

- ^ a b Howe, Daniel W. (2007). What hath God Wrought, The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. Oxford University Press, Inc. ISBN 978-0-19-507894-7.

- ^ a b Howe, pp. 8–73, 329–366.

- ^ Hearn, p. 11.

- ^ Howe, pp. 671–700.

- ^ Hearn, Chester G. (1995). The Capture of New Orleans 1862. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0-8071-1945-8.

- ^ Foote, Shelby (1986). The Civil War, A Narrative, Fort Sumter to Perryville. Vintage Books. ISBN 0-394-74623-6.

- ^ Hearn, pp. 2–11.

- ^ Allan Nevins: Ordeal of the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862–1863 (1960) p. 99.

- ^ Hearn, p. 237.

- ^ Hearn, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Hearn, pp. 243–245.

- ^ Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events of the year: 1862. New York: D. Appleton & Company. 1863. p. 228.

- ^ Marshall, Jeffrey D. (2004). "'Butler's Rotten Breath of Calumny': Major General Benjamin F. Butler and the Censure of the Seventh Vermont Infantry regiment". Vermont History. Vermont History 72 (Winter/Spring). ISSN 1544-3043.

- ^ Hearn, When the Devil came down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans, Louisiana State University Press 1997, ISBN 0-8071-2623-3, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Hearn, pp. 104–107.

- ^ McCurry, Stephanie (2010). Confederate Reckoning, Power and Politics in the Civil War South. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-04589-7.

- ^ Long, Alecia P. (2009). "(Mis)Remembering General Order No. 28: Benjamin Butler, the Woman Order, and Historical Memory". In Whites, LeeAnn (ed.). Occupied Women: Gender, Military Occupation, and the American Civil War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University. p. 28. ISBN 9780807137178.

- ^ General Orders, No. 28 (Butler's Woman Order)

- ^ Official Records of the American Civil War – Series I – Volume XV [S# 21]

- ^ Hearn, Chester G. (1997). When the Devil Came Down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University. p. 107. ISBN 9780807121801.

- ^ "Our Affairs in England: Gen. Butler's Proclamation in the House of Lords Mediation". The New York Times. June 27, 1862.

- ^ "General Butler". Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art. 14 (364): 463. October 18, 1862.

- ^ "Gen. Butler Defends the Woman Order". The New York Times. July 16, 1862. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

- ^ Rable, George (1992). ""Missing in Action": Women of the Confederacy". In Clinton, Catherine (ed.). Divided Houses: Gender and the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 140. ISBN 0195080343.

- ^ Dowdey, Clifford (1955). The Land They Fought For, The Story of the South as the Confederacy, 1832–1865. Doubleday & Company, Inc., Garden City, NY. p. 28

- ^ Marshall, p. 24.

- ^ Hearn, Capture of New Orleans, p. 41.

- ^ Westwood, Howard C. “Benjamin Butler’s Enlistment of Black Troops in New Orleans in 1862.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 26, no. 1, 1985, pp. 5–22. JSTOR 4232388. Accessed 11 Feb. 2024.

- ^ Hearn, When the Devil came down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Marshall, p. 28.

- ^ a b McCurry, pp. 253–260, 271–273.

- ^ a b Hearn, When the Devil came down to Dixie: Ben Butler in New Orleans, p. 4.

- ^ Johnson, Ludwell H. (1993). Red River Campaign, Politics & Cotton in the Civil War. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-486-5.

References

External links

- Newspaper coverage of the capture of New Orleans Archived December 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Map: 29°57′27″N 90°03′47″W / 29.95750°N 90.06306°W