Battle of New Hope Church

| Battle of New Hope Church | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

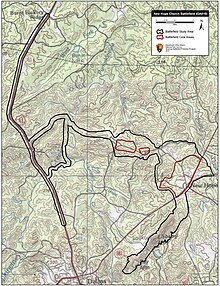

New Hope Battlefield Park, a memorial located at the site of the battle | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of Tennessee | Military Division of the Mississippi | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,000, 16 guns | 16,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 400 | 1,665 | ||||||

The Battle of New Hope Church (May 25–26, 1864) was a clash between the Union Army under Major General William T. Sherman and the Confederate Army of Tennessee led by General Joseph E. Johnston during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. Sherman broke loose from his railroad supply line in a large-scale sweep in an attempt to force Johnston's army to retreat from its strong position south of the Etowah River. Sherman hoped that he had outmaneuvered his opponent, but Johnston rapidly shifted his army to the southwest. When the Union XX Corps under Major General Joseph Hooker tried to force its way through the Confederate lines at New Hope Church, its soldiers were stopped with heavy losses.

Earlier in May, Sherman successfully maneuvered Johnston's army into retreating from three separate defensive positions. However, when Sherman's army crossed the Etowah River and attempted to move around Johnston's left flank, the Confederate general anticipated his opponent's intentions. Sherman believed that the way was clear, when in fact, Johnston quickly shifted his army into a blocking position. At New Hope Church, Hooker's corps aggressively pressed forward but its attack received a stinging repulse from one division of John Bell Hood's Confederate corps, which was well-entrenched. Thwarted, Sherman next tried to move around Johnston's right flank.

Background

Union Army

On April 30, Sherman's host numbered 110,000 soldiers of which 99,000 were available for "offensive purposes".[1] All of the Union army's 254 guns consisted of 12-pounder Napoleons, 10-pounder Parrott rifles, 20-pounder Parrott rifles, and 3-inch Ordnance rifles.[2] The 25,000 non-combatants accompanying the army included railroad employees and repair crews, teamsters, medical staff, and Black camp servants. Sherman directed elements of three armies. The Army of the Cumberland led by Major General George H. Thomas counted 73,000 troops and 130 guns, the Army of the Tennessee under Major General James B. McPherson numbered 24,500 soldiers and 96 guns, and the Army of the Ohio commanded by Major General John Schofield had 11,362 infantry, 2,197 cavalry, and 28 guns.[1]

Thomas' army consisted of the IV Corps under Major General Oliver Otis Howard, the XIV Corps under Major General John M. Palmer, the XX Corps under Major General Joseph Hooker, and three cavalry divisions led by Brigadier Generals Edward M. McCook, Kenner Garrard, and Hugh Judson Kilpatrick. McPherson's army comprised the XV Corps under Major General John A. Logan and the Left Wing of the XVI Corps under Brigadier General Grenville M. Dodge. The XVII Corps under Major General Francis Preston Blair Jr. did not join until June 8. Schofield's army was made up of the XXIII Corps under Schofield and a cavalry division led by Major General George Stoneman.[3] The IV and XX Corps each counted 20,000 soldiers, the XIV Corps had 22,000, the XV Corps totaled 11,500, and the XVI and XVII Corps each numbered about 10,000 men.[4][note 1]

Confederate Army

On April 30, Johnston's army counted 41,279 men present for duty in seven infantry divisions. There were 3,227 artillerymen present for duty serving 144 guns. Many of the guns were inferior to the Federal artillery pieces, but the crews were experienced. There were 10,000 cavalrymen, but only 8,500 present for duty and many horses were in poor condition. There were probably 8,000 non-combatants supporting the army, many of whom were disabled by wounds or otherwise unfit for combat.[5] Johnston's Army of Tennessee included two infantry corps led by Lieutenant Generals William J. Hardee and John Bell Hood, and a cavalry corps under Major General Joseph Wheeler. The army was soon joined by the corps of Lieutenant General Leonidas Polk and the cavalry division of Brigadier General William H. Jackson. Hardee's corps consisted of the divisions of Major Generals Benjamin F. Cheatham, Patrick Cleburne, William H. T. Walker, and William B. Bate. Hood's corps included the divisions of Major Generals Thomas C. Hindman, Carter L. Stevenson, and Alexander P. Stewart. Polk's corps comprised the divisions of Major Generals William Wing Loring and Samuel Gibbs French, and Brigadier General James Cantey.[6]

Operations

Sherman launched his campaign on May 7, 1864, with the Battle of Rocky Face Ridge during which he turned Johnston's western flank. This was followed by the Battle of Resaca on May 13–15 at which time Polk's corps began arriving. After Sherman turned his western flank again, Johnston withdrew. At the Battle of Cassville, Johnston tried to strike at Sherman's army, but the opportunity was fumbled. On May 19, Polk and Hood convinced Johnston to retreat to Allatoona Pass.[7] Johnston conducted the withdrawal south of the Etowah River skillfully, leaving few stragglers behind. Schofield's corps passed through Cartersville and reached the Etowah to find the bridges burnt and the Confederates gone. The Western and Atlantic Railroad ran through a gorge at Allatoona Pass and Johnston posted his army there in an extremely strong defensive position.[8]

Sherman planned to force Johnston's army to retreat behind the Chattahoochee River. To do this he decided to outflank Johnston's army on the west by marching to Dallas and then Marietta. On May 20, Sherman ordered his army to be ready to move on May 23. Since it would be leaving the railroad line, the army carried 20 days of supplies in its wagons and evacuated all its wounded and unfit men to the rear. Sherman was anxious about his railroad supply line which ran 80 mi (129 km) back to Chattanooga. Fearing the railroad might be damaged by Confederate cavalry raids, Sherman ordered Brigadier General John E. Smith's XV Corps division from Huntsville, Alabama, and nine XXIII Corps regiments from East Tennessee and Kentucky forward to guard the Western and Atlantic Railroad. To replace these units, he summoned northern state governors to recruit 100-day regiments to garrison the rear area railroads.[9]

Sherman directed McPherson's two corps on his right wing to march from Kingston south to Van Wert and then east to Dallas. Since Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis' division (XIV Corps) was already to the west at Rome, it moved with McPherson. Thomas' three corps were ordered to march south through Euharlee and Stilesboro toward Dallas. Garrard's cavalry covered McPherson's wing, while McCook's horsemen scouted ahead of Thomas's center. Preceded by Stoneman, Schofield's left wing marched from Cartersville to the Etowah. Stoneman's cavalry found Milam's Bridge burned and a pontoon bridge was laid nearby. Hooker crossed his XX Corps ahead of Schofield's XXIII Corps and therefore was able to move ahead of Thomas' other two corps.[10]

Unsure if Sherman was moving around his left flank, Johnston ordered Wheeler's cavalry to cross to the north bank of the Etowah to see if Sherman's army was still there. On May 24 Wheeler reported that Sherman's army was to the west near Kingston. Avoiding Kilpatrick's cavalry, which was patrolling the area, Wheeler's horsemen captured 70 wagons and burned others.[11] Also on May 24, McPherson reached a point 8 mi (13 km) west of Dallas. Riding ahead, Garrard's troopers reported that Confederate infantry was at Dallas. Hooker reached Burnt Hickory ahead of Thomas' other corps; Schofield's corps was to the northeast. Alerted by reports from Jackson's cavalry division, Johnston deduced that the Union army was maneuvering to turn his left flank. That afternoon, McCook's horsemen captured a Confederate courier with a message that Johnston's army was moving toward Dallas. Nevertheless, Sherman remained confident that Johnston would not try to block him at Dallas; he ordered his army to press forward.[12]

Battle

On the morning of May 25, Hardee's corps took position at Dallas, blocking the road to Marietta, with Polk's corps on its right flank. On the far right flank, Hood's corps moved into position near New Hope Church, northeast of Dallas. Hood posted Hindman's division on the left flank and Stevenson's division on the right flank. Stewart's division deployed in the center, reinforced by one of Stevenson's brigades. Hood's soldiers immediately dug rifle pits and piled up breastworks of logs and rocks. Confederate observers on Elsberry Mountain reported seeing dust clouds that indicated Sherman's troops were coming. That afternoon, Hood's troops captured a Union soldier who admitted that he belonged to Hooker's corps.[13]

On May 25, McPherson's left wing took the road southeast from Van Wert to Dallas. Davis' division turned off to the east on a side road. Hooker's XX Corps marched on the road from Burnt Hickory to Dallas, with Brigadier General John W. Geary's division on the main road. The other divisions advanced on minor roads, with Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams to the right and Major General Daniel Butterfield to the left of the main road. The IV and XIV Corps marched to the right of Hooker's corps and Schofield's corps remained close to Burnt Hickory.[14] At Pumpkinvine Creek, the Federals found some Confederates trying to set the bridge on fire. Hooker's cavalry escort drove off the bridge-burners and Geary's troops crossed the stream.[13] At the left fork in the road near Owen's Mills, Geary's division took the route toward New Hope Church. As his column advanced, it was met by determined resistance by the 32nd Alabama and 58th Alabama Infantry Regiments and Austin's Sharpshooters under Colonel Bushrod Jones. Geary was compelled to deploy Colonel Charles Candy's brigade in an extended skirmish line in order to drive Jones' Confederates back.[15]

Geary's troops took several prisoners who told them that Hood's corps was directly ahead. Both Thomas and Hooker were startled by this information because, like Sherman, they did not expect to run into major opposition so soon. Fearing that Geary's troops were exposed to a sudden attack, Thomas summoned the divisions of Williams and Butterfield to march rapidly to Geary's assistance.[17] Having marched down the right fork toward Dallas, Williams' troops had to retrace their route to Owen's Mills, then turn right into the road Geary had taken.[15] Between 4 pm and 5 pm, both Williams' and Butterfield's troops reinforced Geary. Still convinced that only minor Confederate forces were in the Dallas area, Sherman ordered Thomas to attack; Thomas passed the order to Hooker.[18]

Soon after 5 pm, Hooker gave the order to attack, with Williams' division on the right and Butterfield's division on the left and Geary's division in support. Butterfield's line was slightly behind Williams in order to protect against a flank attack.[18] All three divisions were formed in columns of brigades. That is, within each division, each brigade was deployed in line, one behind the other.[19] All three divisions advanced about 1 mi (1.6 km) through dense woods and underbrush. In Williams' division, Hooker and Williams rode behind the first brigade. When the troops reached the bottom of a slope, they were greeted by a storm of rifle and artillery fire. The Union soldiers threw themselves to the ground behind whatever cover they could find and fired back. As they came under fire, Butterfield's and Geary's soldiers also lay down.[18] The 4,000 Confederate defenders belonged to Stewart's division, with the brigades of Brigadier Generals Marcellus Augustus Stovall, Henry D. Clayton, and Alpheus Baker in the front line, from left to right, and Brigadier General Randall L. Gibson's brigade in reserve. Stewart's line was also supported by 16 cannons. Though facing 16,000 Federals, Stewart's entrenched soldiers had no trouble defending their position.[20]

The Union generals hoped that their opponents would be caught in the open, but it became clear that the Confederates were protected by earth and log field fortifications. The only clearly visible target was a Confederate artillery battery, which took casualties. Williams' first brigade under Colonel James S. Robinson fired off its 60 rounds per man and was replaced in the battle line by Brigadier General Thomas H. Ruger's brigade. Brigadier General Joseph F. Knipe's brigade waited in the third line. Johnston, who arrived at Hood's headquarters that afternoon, asked Stewart if he needed reinforcements.[21] Stewart replied, "My own troops will hold the position." The battle went on for three hours, and during the last hour a thunderstorm added its noise and rain to the din of battle. Hooker reported suffering 1,665 killed and wounded. The Union troops called the battlefield the "Hell Hole".[22] As the defeated Federals slowly withdrew, the Confederates gave a cheer. Stewart reported losing 300–400 casualties.[23] Another source stated there were 1,665 Union and 400 Confederate casualties.[24]

Aftermath

Johnston and Hood both commended Stewart for his successful defense. On the other hand, Sherman was badly disappointed that his maneuver was so unexpectedly blocked. Sherman hated Hooker and unfairly criticized him for not immediately pushing ahead with Geary's division. Sherman believed that by waiting for his other two divisions to arrive, Hooker allowed the Confederates time to entrench. He hoped that he was only facing Hood's corps, but it was finally beginning to dawn on him that Johnston's entire army was in front of him. The sound of fighting was heard in Atlanta and caused a minor panic among the civilians there.[23]

During the night, the Union army entrenched, and skirmishing continued throughout May 26. McPherson's wing and Davis' division occupied Dallas in the afternoon and established a position two miles farther east. The troops of Thomas and Schofield concentrated near New Hope Church. A 1 mi (1.6 km) gap existed between Thomas and McPherson, but it was concealed by the heavily wooded terrain. Likewise, there was a gap between Hardee's corps east of Dallas and the corps of Hood and Polk at New Hope Church. Johnston detached Cleburne's division from Hardee and added it to his right flank. Thwarted in his attempt to turn the Confederate left flank, Sherman decided to attack the Confederate right flank.[25] His efforts resulted in the Battle of Pickett's Mill on May 27.[26]

Battlefield

Much of the New Hope Church battlefield is today privately owned and is located at the intersection of Bobo Road and Hwy 381 (Dallas Acworth Hwy) in Dallas. The American Battlefield Trust and its partners have acquired and preserved almost five acres of the battlefield as of mid-2023.[27]

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Dodge was promoted Major General on June 7, 1864. (Boatner, p. 243)

- Citations

- ^ a b Castel 1992, p. 112.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 115.

- ^ Battles & Leaders 1987, pp. 284–289.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 113.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 106–111.

- ^ Battles & Leaders 1987, pp. 289–292.

- ^ Boatner 1959, pp. 30–32.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 68.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 220.

- ^ a b Castel 1992, p. 221.

- ^ Cox 1882, pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b Cox 1882, p. 72.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 71.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 221–222.

- ^ a b c Castel 1992, p. 223.

- ^ Cox 1882, p. 73.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 224–225.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 223–225.

- ^ Foote 1986, p. 348.

- ^ a b Castel 1992, p. 226.

- ^ American Battlefield Trust 2021.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 228–229.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 234.

- ^ "New Hope Church Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved June 20, 2023.

References

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 4. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987 [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-572-8.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Castel, Albert E. (1992). Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0562-2.

- Cox, Jacob D. (1882). "Atlanta". New York, N.Y.: Charles Scribner's Sons. Retrieved September 7, 2021.

- Foote, Shelby (1986). The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y.: Random House. ISBN 0-394-74622-8.

- "New Hope Church Battlefield". American Battlefield Trust. 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

See also

- "Battle of New Hope Church Monument Dedication". Sons of Confederate Veterans: Hardee Camp #1397. May 25, 2014. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- "The Campaign for Atlanta: The "Hell Hole" (May 21-June 6)". National Park Service. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide. Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- "New Hope Church". American Battlefield Trust. 2021. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- "New Hope Church Map". American Battlefield Trust. 2021. Retrieved September 9, 2021. This is an excellent map.