Battle of Jackson

| Battle of Jackson | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

The Battle of Jackson, Mississippi by Alfred E. Mathews, 31st Ohio, shows the charge of the 17th Iowa, 80th Ohio and 10th Missouri on May 14, 1863 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

XV Corps XVII Corps | Jackson Garrison | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 286–332 | c. 200–850 | ||||||

Location in Mississippi | |||||||

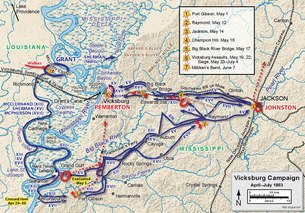

The Battle of Jackson was fought on May 14, 1863, in Jackson, Mississippi, as part of the Vicksburg campaign during the American Civil War. After entering the state of Mississippi in late April 1863, Major General Ulysses S. Grant of the Union Army moved his force inland to strike at the strategic Mississippi River town of Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Battle of Raymond, which was fought on May 12, convinced Grant that General Joseph E. Johnston's Confederate army was too strong to be safely bypassed, so he sent two corps, under major generals James B. McPherson and William T. Sherman, to capture Johnston's position at Jackson. Johnston did not believe the city was defensible and began withdrawing. Brigadier General John Gregg was tasked with commanding the Confederate rear guard, which fought Sherman's and McPherson's men at Jackson on May 14 before withdrawing. After taking the city, Union troops destroyed economic and military infrastructure and also plundered civilians' homes. Grant then moved against Vicksburg, which he placed under siege on May 18 and captured on July 4. Despite being reinforced, Johnston made only a weak effort to save the Vicksburg garrison, and was driven out of Jackson a second time in mid-July.

Prelude

In early 1863, during the American Civil War, Major General Ulysses S. Grant of the Union Army was planning operations against the strategic Confederate-held Mississippi River city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. After early efforts failed, Grant decided to move south of the city on the opposite side of the river, and then cross the Mississippi to move against the town and its garrison. In late April, 24,000 Union soldiers were landed at Bruinsburg, Mississippi, as part of that plan.[1] Grant's men fought their way inland and then moved east with the intention of later turning to the west and attacking Vicksburg from that direction. The movement was conducted in three columns.[2] Meanwhile, Confederate troops from across the country were dispatched to reinforce the defenders of Vicksburg. The reinforcements gathered at Jackson, Mississippi, and on May 10, General Joseph E. Johnston was sent to command the growing force.[3] Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, the commander of the Vicksburg garrison, ordered one of the units at Jackson, Brigadier General John Gregg's brigade, to move to the town of Raymond.[4]

On May 12, one of the Union columns, under the command of Major General James B. McPherson, encountered Gregg's Confederates near Raymond. The ensuing Battle of Raymond was a Union victory, although McPherson's poor handling of the battle allowed the badly-outnumbered Confederates to prolong the battle. The fighting at Raymond changed Grant's approach to the campaign. Realizing that the Confederate force in Jackson was stronger than he had believed, Grant was unwilling to leave the enemy force in his rear and decided to send his men against the Jackson position.[5] Unsure if McPherson's XVII Corps was strong enough to take the city, Grant ordered McPherson to attack Jackson from the northwest, while Major General William T. Sherman's XV Corps struck from the southwest.[6]

Johnston, who had a reputation for defeatism,[7][8] arrived in Jackson on May 13. About 6,000 Confederate troops held the city, including Gregg's recently defeated men, although additional reinforcements were expected. During his journey to Jackson, Johnston had learned that Grant's army had moved into Mississippi, while Pemberton's force was holding a defensive position along the Big Black River. The Union force was between the Confederate positions.[7] Johnston decided that Jackson could not be held in what the historians William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel described as "unseemly haste", sent a telegram to his commanding officers in Richmond, Virginia, stating "I am too late", and ordered the evacuation of the city.[6] While Johnston and his staff made the 25-mile (40 km) retreat to Canton by rail, the rest of his army made the retreat on foot.[6][7] Gregg's men were tasked with serving as a rear guard at Jackson. While retreating, Johnston sent Pemberton a misleading message suggesting that Johnston's men would support Pemberton in an offensive movement when he had no intention of doing so. The historian Donald L. Miller believes that this was designed to present the appearance in the official records that he was not abandoning Vicksburg.[9]

Battle

On May 14, the Union soldiers made contact with the Confederate rear guard 5 miles (8.0 km) from Jackson during a thunderstorm.[10] Two Confederate officers, Brigadier General W. H. T. Walker and Colonel Peyton Colquitt had formed a roadblock outside of town with their brigades, but the rainfall forced the action to halt. During the respite provided by the rain, the Confederates learned of Sherman's approach, and sent a unit of mounted infantry to confront his column. After the rain stopped, the Union advance resumed.[11] The delay during the rain had been necessary to prevent the paper cartridges used at the time from becoming waterlogged and unusable.[12] McPherson, unsure of the strength of the force he was facing, initially acted cautiously, using artillery fire to probe the Confederate lines. After determining that he was not facing a large force, McPherson ordered Brigadier General Marcellus M. Crocker's division to attack the Confederate lines.[10] Initial Confederate resistance cost McPherson about 300 casualties,[12] but Crocker's attack forced the Confederate pickets back into the fortifications around Jackson, and the Union soldiers soon carried the main defenses as well.[10] By the time McPherson's men had reached the fortifications, all of the Confederate defenders except for the crews of seven cannons had withdrawn.[12]

Sherman's advance met less opposition. Only small amount of artillery fire resisted his advance, and Sherman detached the 95th Ohio Infantry Regiment to test the Confederate fortifications. The Ohio regiment found that the position had been abandoned, and were informed by an African American civilian that only a token Confederate artillery force remained. When Sherman's overall advance occurred not long afterwards, these artillerymen were captured and found to be militiamen and armed civilians.[13] In addition to the seven cannons captured by McPherson's men, Sherman's advance took a further ten.[14]

Aftermath

After taking the town, the Union soldiers, primarily Sherman's men, demolished infrastructure in the city. Factories, warehouses, and other military and economic sites were destroyed.[15] Grant and Sherman personally visited a textiles plant before Sherman ordered its destruction.[16] Iron rails of the Southern Railroad of Mississippi were damaged by bending them into circular shapes known as Sherman's neckties. Despite official orders from Sherman prohibiting such behavior, civilian homes were also plundered and burned. Between fires that had been set by retreating Confederates destroying supplies and those set by Union troops during the occupation, Jackson suffered significant fire damage.[15] For a time, Grant had his headquarters in the same building that Johnston had stayed in while he was in the town.[11]

Estimates of casualties suffered in the battle vary. The historian Shelby Foote stated that the Confederates lost a little over 200 men, while Grant lost 332: 48 killed, 273 wounded, and 11 missing.[14] Historians William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel place Union losses at 300 (42 killed, 251 wounded, and 7 missing), while putting Confederate losses at about 845 men; the National Park Service agrees with both figures.[16][17] The Civil War Battlefield Guide, edited by Frances Kennedy, gives Union losses as 286 men and Confederate losses as 850.[18] Almost all of the Union losses were suffered by McPherson's corps.[14][16]

After Jackson was captured, the forces of Johnston and Pemberton were cut off from each other.[18] On May 16, Grant's men defeated Pemberton decisively at the Battle of Champion Hill.[19] By May 18, the Union soldiers had reached Vicksburg and placed the city under siege. The siege of Vicksburg continued until July 4, when Pemberton surrendered.[20] During the siege, reinforcements from across the Confederacy continued to be diverted to Johnston, who eventually amassed 32,000 men. Named the Army of Relief, Johnston's force did not move against Grant until July 1, and then upon reaching the Union lines at the Big Black River two days later, decided that the defenses could not be taken and did not bring on a battle.[21] Johnston ordered a retreat on July 5, and on July 7, Johnston's retreating troops reoccupied Jackson. Grant responded by sending Sherman with 46,000 men to follow Johnston. This movement, known as the Jackson Expedition, reached the city of July 10.[22] The city was soon placed under siege; a limited Union attack that mistakenly occurred was repulsed on July 12. Johnston again abandoned Jackson on the night of July 16/17.[23]

Battlefield preservation

The City of Jackson preserves 2 acres (0.81 ha) of the battlefield: one in a public park and another on the campus of the University of Mississippi Medical Center.[24]

References

Citations

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Bearss 1998, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Bearss 2007, p. 216.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 121.

- ^ Bearss 1998, pp. 164–166.

- ^ a b c Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Miller 2019, p. 388.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 124.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 388–389.

- ^ a b c Miller 2019, p. 391.

- ^ a b Bearss 2007, p. 221.

- ^ a b c Foote 1995, p. 182.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 125–126.

- ^ a b c Foote 1995, p. 183.

- ^ a b Miller 2019, pp. 392–393.

- ^ a b c Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 126.

- ^ "Battle of Jackson (May 14)". National Park Service. February 15, 2018. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1998, p. 167.

- ^ Bearss 1998b, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Bearss 1998c, pp. 171–173.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 182–184.

- ^ National Park Service 2010, p. 5.

Sources

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Raymond, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 164–167. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Champion Hill, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 171–173. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Battle and Siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 164–167. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (2007) [2006]. Fields of Honor. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0093-9.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Foote, Shelby (1995) [1963]. The Beleaguered City: The Vicksburg Campaign (Modern Library ed.). New York: The Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60170-8.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Shea, William L.; Winschel, Terrence J. (2003). Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9344-1.

- Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation's Civil War Battlefields: State of Mississippi (PDF). Washington, D. C.: National Park Service. 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

External links

Media related to Battle of Jackson at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Battle of Jackson at Wikimedia Commons