Baden, Switzerland

Baden | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 47°28′N 8°18′E / 47.467°N 8.300°E | |

| Country | Switzerland |

| Canton | Aargau |

| District | Baden |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Stadtrat with 7 members |

| • Mayor | Stadtammann (list) Markus Schneider CVP/PDC (as of February 2018) |

| • Parliament | Einwohnerrat with 50 members |

| Area | |

• Total | 13.17 km2 (5.08 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 381 m (1,250 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2018)[2] | |

• Total | 19,340 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,800/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Badener |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (Central European Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (Central European Summer Time) |

| Postal code(s) | 5400 |

| SFOS number | 4021 |

| ISO 3166 code | CH-AG |

| Surrounded by | Birmenstorf, Ennetbaden, Fislisbach, Gebenstorf, Mellingen, Neuenhof, Obersiggenthal, Turgi, Wettingen |

| Twin towns | Sighişoara (Romania) |

| Website | www SFSO statistics |

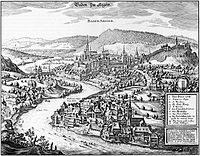

Baden (German for "baths"),[3] sometimes unofficially, to distinguish it from other Badens, called Baden bei Zürich ("Baden near Zürich")[4] or Baden im Aargau ("Baden in the Aargau"),[5] is a town and a municipality in Switzerland. It is the main town or seat of the district of Baden in the canton of Aargau. Located 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Zürich in the Limmat Valley (German: Limmattal) mainly on the western side of the river Limmat, its mineral hot springs have been famed since at least the Roman era. Its official language is (the Swiss variety of Standard) German, but the main spoken language is the local Alemannic Swiss-German dialect. As of 2018 the town had a population of over 19,000.

Geography

Downtown Baden is located on the left bank of the river Limmat in its eponymous valley.[6] Its area is divided into the Kappelerhof, Allmend, Meierhof, and Chrüzliberg. In 1962, Baden also absorbed the adjacent village of Dättwil. On the right bank of the river is the village of Ennetbaden, formerly "Little Baden" (Kleine Bäder).[7]

Baden has an area, (as of the 2004/09 survey) of 13.17 km2 (5.08 sq mi).[8] Of this area, about 8.6% is used for agricultural purposes, while 55.8% is forested. Of the rest of the land, 33.7% is settled (buildings or roads) and 1.8% is unproductive land. In the 2004/09 survey a total of 275 ha (680 acres) or about 20.8% of the total area was covered with buildings, an increase of 44 ha (110 acres) over the 1982 amount. Over the same time period, the amount of recreational space in the municipality increased by 4 ha (9.9 acres) and is now about 3.18% of the total area. Of the agricultural land, 14 ha (35 acres) is used for orchards and vineyards and 107 ha (260 acres) is fields and grasslands. Since 1982 the amount of agricultural land has decreased by 53 ha (130 acres). Over the same time period the amount of forested land has decreased by 3 ha (7.4 acres). Rivers and lakes cover 26 ha (64 acres) in the municipality.[9][10]

The hot sulfur springs, which given Baden its name, lie north of downtown[6] and number about 20.[11] They vary in temperature from 98 to 126 °F (37 to 52 °C).[11]

History

Baden is first attested in Roman sources as Aquae Helveticae ("Waters of the Helvetii").[12] Hippocrates had counseled against the use of water from mineral springs,[13] but by the time of Vitruvius,[14] Pliny,[15] and Galen they were being selectively employed for certain ailments.[13] In addition to their medical use, the Romans also revered natural springs for recreational[16] and religious use.[17] Tacitus mentions the town obliquely, describing it as "a place built up into a semblance of a town... much used for its healthful waters".[note 1] This Roman vicus was to the north of the Baden gorge on the Haselfeld, founded to support the legionary camp at Vindonissa. There was a pool complex on the left bank of the Limmat fed by a system of springs with 47 °C (117 °F) water. The main axis of the vicus was the Vindonissa road, which ran parallel to the slope. It was flanked by porticos, beyond which lay commercial and residential buildings. The center of the settlement had some wealthy villa-like structures. The resort, residential, and commercial districts all grew to a respectable size over the first half of the 1st century. In AD 69, however, the 21st Legion burned the town amid the conflicts of the Year of the Four Emperors. Its wooden buildings destroyed, the town was rebuilt in stone. The town shrank some after the closing of the Vinonissa camp in AD 101 but survived on trade. Reginus's pottery workshop and Gemellianus's bronze works flourished during the second half of the 2nd century.[7] Around the middle of the 3rd century, however, the settlement was threatened by multiple Alemanni invasions and the Huns.[11] The pools were fortified and a large number of coins stamped with references to the hot springs show it continued to be settled and frequented into late antiquity, but expansion of the settlement of Haselfeld came to an end.[7]

The baths were frequented again by the time of Charlemagne.[11] A medieval necropolis in Kappelerhof has been dated as far back as the 7th century and a local lord fortifying the Stein by the 10th.[7] The modern name Baden is first attested in 1040.[7] Around that time, its land was held by the Lenzburgs, some of whom styled themselves as the "Counts of Baden" in the 12th century and erected a castle.[19] Upon their extinction around 1172, their domains were divided among the Hohenstaufens, Zähringens, and Kyburgs, with the Kyburgs gaining control of Baden through the marriage of Harmanns III with its heiress Richenza.[20] Around 1230, they founded the medieval city of Baden,[20] holding markets and erecting a bridge across the river in 1242.[7] Upon the death of the childless Hartman IV in 1264, his lands were seized by Rudolf von Habsburg by right of his wife Gertrude's claim. Stein Castle was held by Habsburg bailiffs and maintained the administration and archives for their surrounding territory.[7] The Confederacy besieged and destroyed the castle and its records in 1415 during its conquest of Aargau.[7] Thus, the County of Baden was established.

Under the Confederation, their bailiff held a castle on the right bank of the Limmat, controlling access to the bridge.[6] The Swiss Diet met at Baden repeatedly from 1426 to about 1712, making Baden a kind of capital for Switzerland.[6] The Town Hall (Rathaus), where the Diet met, can still be visited. Over the course of the 15th century, the town regained its popularity as a Spa Resort (Kurort).[11] The town was the site of a famous debate[11] on transubstantiation from May 21 to June 18, 1526. Although Zwingli refused to attend in person, he printed broadsheets throughout its duration and sent his assistant Johannes Oecolampadius to debate Johann Eck and Thomas Murner. In the end, a majority decided against the reformers but a substantial bloc emerged on their behalf as well. Johann Pistorius held a disputation in the city in 1589.[11] Stein was refortified sometime between 1658 and 1670 but the fortress was abandoned in 1712.[7] In 1714, the treaties of Rastatt and Baden ended hostilities between France and the Habsburgs, the last theater of the War of the Spanish Succession.[11] Another Treaty of Baden ended the Toggenburg War among the Protestant and Catholic Swiss cantons in 1718.[11] Baden was the capital of the canton of Baden from 1798 until 1803, when the canton of Aargau was created.[6]

In the 19th century, the waters were considered efficacious for gout and rheumatism.[6] They were frequented by Goethe, Nietzsche, Thomas Mann, and particularly often by Hermann Hesse, who visited the town annually over almost thirty years.[citation needed] The SNB connecting Zürich to Baden was Switzerland's first railway, opening in 1847. Prior to the First World War, foreign visitors were few in number, but the summer tourist season was thought to swell the town.[6] Around the same time, an industrial quarter opened up NW of the baths.[6]

Modern excavations have discovered three Roman bathing pools.[7] The municipalities of Baden and Neuenhof were considering a merger on 1 January 2012 into a new municipality which would have also been known as Baden. This was rejected by a popular vote in Baden on 13 June 2010.[21][22] On 1 January 2024, the former municipality of Turgi was merged into Baden.

Demographics

Baden has a population (as of December 2020) of 19,621.[23] As of 2015, 26.7% of the population are resident foreign nationals. In 2015 a small minority (1,261 or 6.6% of the population) was born in Germany.[24] Over the last 5 years (2010–2015) the population has changed at a rate of 6.04%. The birth rate in the municipality, in 2015, was 12.4, while the death rate was 6.9 per thousand residents.[10]

Most of the population (as of 2000) speaks German (83.8%), with Italian being second most common (3.3%) and Serbo-Croatian being third (3.0%).[25]

As of 2015, children and teenagers (0–19 years old) make up 17.6% of the population, while adults (20–64 years old) are 66.9% of the population and seniors (over 64 years old) make up 15.6%.[10] In 2015 there were 9,390 single residents, 7,371 people who were married or in a civil partnership, 744 widows or widowers, 1,506 divorced residents and 1 people who did not answer the question.[26]

In 2015 there were 8,996 private households in Baden with an average household size of 2.09 persons. In 2015 about 52.2% of all buildings in the municipality were single family homes, which is much less than the percentage in the canton (67.4%) and less than the percentage nationally (57.4%).[27] Of the 2,858 inhabited buildings in the municipality, in 2000, about 53.9% were single family homes and 25.2% were multiple family buildings. Additionally, about 19.4% of the buildings were built before 1919, while 11.1% were built between 1991 and 2000.[28] In 2014 the rate of construction of new housing units per 1000 residents was 5.25. The vacancy rate for the municipality, in 2016, was 0.34%.[10]

The historical population is given in the following chart:[29]

Economy

Baden is a medium-sized regional center and the center of the agglomeration of Baden – Brugg.[30]

As of 2014, there were a total of 29,858 people employed in the municipality. Of these, a total of 69 people worked in 8 businesses in the primary economic sector, of which two employed a total of 49 employees. The secondary sector employed 9,081 workers in 174 separate businesses. There were 10 mid-sized businesses with a total of 1,138 employees and 6 large businesses which employed 6,519 people (for an average size of 1,087). Finally, the tertiary sector provided 20,708 jobs in 2,173 businesses. In 2013 there were 5 and 123 new companies founded in the secondary and tertiary sector, respectively. In 2014 a total of 12,672 employees worked in 2,124 small companies (less than 50 employees). There were 45 mid-sized businesses with 4,896 employees and 4 large businesses which employed 3,140 people (for an average size of 785).[31] In 2014 the number of new businesses was 9 and 133. These new businesses employed a total of 204 workers in 2013, and a total of 232 in 2014.[32]

In 2015 a total of 5.2% of the population received social assistance.[10] In 2011 the unemployment rate in the municipality was 3.1%.[33]

In 2015 local hotels had a total of 87,062 overnight stays, of which 66.9% were international visitors.[34]

In 2015 the average cantonal, municipal and church tax rate in the municipality for a couple with two children earning SFr 80,000 was 4% while the rate for a single person earning SFr 150,000 was 14.5%, both of which are close to the average for the canton. In 2013 the average income in the municipality per tax payer was SFr 87,822 and the per person average was SFr 44,022, which is greater than the cantonal averages of SFr 79,140 and SFr 35,073 respectively It is also greater than the national per tax payer average of SFr 82,682 and the per person average of SFr 35,825.[35]

As of 2000 there were 9,223 total workers who lived in the municipality. Of these, 5,567 or about 60.4% of the residents worked outside Baden while 15,103 people commuted into the municipality for work. There were a total of 18,759 jobs (of at least 6 hours per week) in the municipality.[36]

In the 19th and 20th century Baden became an industrial town, main seat of the former Brown Boveri Company. Most industrial facilities have moved, but Baden is still the seat of many of the engineering services of ABB and several branches of GE's Power business which was acquired from Alstom in 2015. The former industrial quarter to the north of the city is now being redeveloped into offices, shopping and leisure facilities.

There is also a Casino in Baden.[37]

Coat of arms

The blazon of the municipal coat of arms is Argent a Pale Sable and a chief Gules.[38]

Sights

The Heisse Brunnen is a pool with hot water, built in 2021. It can be used from 7 am to 10 pm. The use is for free.[39] The old town, the Tagsatzung room in the city hall, the 1847 railway station and the building of the Stiftung Langmatt are listed as heritage sites of national significance.[40]

In addition to the Roman city, the ruins of castle Stein and the other sites listed above, Baden is home to a number of other Swiss Heritage Sites. The industrial sites include the ABB Schweiz archive along with the former offices of Brown Boveri Company as well as the regional former utilities plant on Haselstrasse 15. There are three designated religious buildings in Baden; the Catholic city church and Sebastians chapel, the Swiss Reformed parish church and the Synagogue on Parkstrasse 17. Perhaps included in the last two groups is the Crematorium and memorial hall on Zürcherstrasse 108. The wooden bridge between Untere Halde and Wettingerstrasse is also included in the list. A number of individual buildings are also included in the inventory. These include; Bernerhaus at Weite Gasse 13, Haus Zum Schwert on Schwertstrasse or Oelrainstrasse 29, the Hotel Verenahof, the Hotel Zum wilden Mann, the spa-theater with a glass foyer at Parkstrasse 20, the Restaurant Paradies on Cordulaplatz, Villa Boveri (since 1943 Clubhaus BBC/ABB) and the Villa Langmatt (now Museum Langmatt, an art museum[41][42]) at Römerstrasse 30.

The village of Baden is designated as part of the Inventory of Swiss Heritage Sites.[43]

Baden is also known for the traditional delicacy Spanisch Brötli, which is being made once again after a lapse of some years.

- Ruins of Stein Castle

- City Church of Baden

- Swiss Reformed church of Baden

- Villa Langmatt, now an art museum

- Stadthaus, part of the city hall complex

- Tagsatzung from 1531

- Wooden bridge over the Limmat

- Baden regional power plant, part of the utilities plant

Surrounding area

2 km (1.2 mi) south of Baden, on a distinct peninsula of the Limmat, is the Cistercian Wettingen Abbey (1227–1841), with old painted glass in the cloisters and early 17th century carved stalls in the choir of the church. 8 km (5 mi) west of Baden is the small town of Brugg (9,500 inhabitants) in a fine position on the Aare, and close to the remains of the Roman colony of Vindonissa (today Windisch), as well as to the monastery (founded 1310) of Königsfelden, formerly the burial-place of the early Habsburgs (the castle of Habsburg is but a short way off), still retaining much fine medieval painted glass.[6] Other areas surrounding Baden along the Limmat are Obersiggenthal (pop. 8170 in 2008), Untersiggenthal (pop. 6424 in 2008), Turgi (pop. 2879 in 2008), all of which have also seen population growth in the same 5-6% per year over the last several years.

Education

The Volksschule Baden, the municipal public primary and secondary school, serves levels Kindergarten through Sekundarstufe I.[44]

The Canton of Aargau school system requires students to attend 11 years of schooling (two kindergarten, six primary school and three lower secondary). The lower secondary level is divided into three tracks, Realschule, Sekundarschule and Bezirksschule. The Realschule has the lowest level of academic difficulty and typically leads to an apprenticeship or vocational school. The Sekundarschule leads to an apprenticeship, vocational education or professional training at a Fachmittelschule. Bezirksschule is the most demanding track and it usually leads to a Mittelschule or Gymnasium.[45] During the 2016/17 school year there were a total of 2,204 students attending mandatory schools in a total of 120 classes. Of these students, 372 were in 22 kindergarten classes. There were a total of 372 primary students in 51 classes (27 of which were multi-age classrooms). There were 108 students attending the Realschule in the municipality, 254 in the Sekundarschule and 420 at the Bezirksschule, with the remainder in apprenticeships or other job training.[46]

In Baden about 79.5% of the population (between age 25-64) have completed either non-mandatory upper secondary education or additional higher education (either university or a Fachhochschule).[25] Of the school age population (in the 2008/2009 school year), there are 995 students attending primary school, there are 377 students attending secondary school, there are 633 students attending tertiary or university level schooling, there are 25 students who are seeking a job after school in the municipality.[47]

Politics

In the 2015 federal election the most popular party was the SP with 22.7% of the vote. The next three most popular parties were the SVP (20.0%), the FDP (18.3%) and the GPS (11.6%). In the federal election, a total of 6,573 votes were cast, and the voter turnout was 56.5%.[48]

In the 2007 federal election the most popular party was the SP which received 24.7% of the vote. The next three most popular parties were the SVP (21.2%), the FDP (16.4%) and the Green Party (15.6%).[25]

Transportation

Baden was the destination of the first railway in Switzerland, the Spanisch Brötli Bahn transporting the richer people from Zürich to the baths of Baden. Today Baden is a regular stop on the railway lines Zürich-Basel and Zürich-Bern. Baden is a stop of the S-Bahn Zürich on the line S12 and a terminal station on the line S6.

The A1 motorway tunnel Baregg is a major junction in the area. It was undergoing construction until 2004 and has been subject to controversy. In 2003, a third tunnel hole was opened to vehicles on the motorway.

Notable people

- Thomas Erastus (1524–1583), a physician and theologian [49]

- Johann Rudolph Rengger (1795–1832), a naturalist, doctor and author of a book on Paraguay

- Charles Eugene Lancelot Brown (1863–1924), joint founder of Brown, Boveri & Cie

- Walter Boveri (1865–1924), joint founder of Brown, Boveri & Cie

- Emil Frey (1889–1946), a composer, pianist and teacher

- Barbara Borsinger (1892–1973), founded hospitals to care for pandemic victims

- Albert Hofmann (1906–2008), chemist, discovered LSD

- Peter Voser (born 1958), a businessman, CEO of Royal Dutch Shell plc 2009–2013

- Alexander Birchler (born 1962), part of Hubbard/Birchler duo who make short films

- Sedmak, Tamara (born 1976), a TV presenter, model and actress [50]

- Pascale Bruderer (born 1977), a politician, President of the National Council 2009/2010

- Sport

- Max Bösiger (born 1933), a boxer, competed at heavyweight in the 1960 Summer Olympics

- Jörg Stiel (born 1968), a retired football goalkeeper, 558 club caps and 21 for his national side

- Karin Ruckstuhl (born 1980), a Dutch heptathlete, competed in the 2004 Summer Olympics

- Giuseppe Aquaro (born 1983), an Italian football defender, about 300 pro games

- Toni Müller (born 1984), a curler, bronze medallist at the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics

Sport

FC Baden is the local football team. They play their home games at the Esp Stadium in Fislisbach, a short distance from Baden.

Baden Basket 54 is based in Baden. Baden Basket 54 plays in SB League Women, the highest tier level of women's professional basketball in Switzerland.

Religion

From the 2000 census, 7,059 or 43.4% are Roman Catholic, while 4,636 or 28.5% belonged to the Swiss Reformed Church. Of the rest of the population, there are 31 individuals (or about 0.19% of the population) who belong to the Christian Catholic faith.[47]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Arealstatistik Standard - Gemeinden nach 4 Hauptbereichen". Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ "Ständige Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeitskategorie Geschlecht und Gemeinde; Provisorische Jahresergebnisse; 2018". Federal Statistical Office. 9 April 2019. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ Charnock (1859), "Baden", Local Etymology, p. 23

- ^ "Baden near Zurich". Google Search. Retrieved 2015-10-09.

- ^ Murray, Alexander (1998), Suicide in the Middle Ages, Vol. I: The Violent Against Themselves, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 28, ISBN 0-19-820539-2

- ^ a b c d e f g h i EB (1911).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Steigmeier (2011).

- ^ Arealstatistik Standard - Gemeindedaten nach 4 Hauptbereichen

- ^ "Arealstatistik Land Use - Gemeinden nach 10 Klassen". www.landuse-stat.admin.ch. Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 24 November 2016. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Regionalporträts 2017: Swiss Federal Statistical Office (in German) accessed 18 May 2017

- ^ a b c d e f g h i EB (1878).

- ^ Campbell (2012), p. 396.

- ^ a b Campbell (2012), p. 343.

- ^ Campbell (2012), p. 339.

- ^ Campbell (2012), p. 340.

- ^ Campbell (2012), pp. 344 ff.

- ^ Campbell (2012), pp. 342–343.

- ^ Tacitus, Hist, Bk. I, Ch. 67.

- ^ Hälg-Steffen (2008b).

- ^ a b Hälg-Steffen (2008a).

- ^ [1] by 20minuten (in German) accessed 11 June 2012

- ^ Amtliches Gemeindeverzeichnis der Schweiz published by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (in German) accessed 14 January 2010

- ^ "Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit". bfs.admin.ch (in German). Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB. 31 December 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office - Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit (Land) accessed 31 October 2016

- ^ a b c Swiss Federal Statistical Office Archived 2016-01-05 at the Wayback Machine accessed 28-January-2010

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office - Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geschlecht, Zivilstand und Geburtsort (in German) accessed 8 September 2016

- ^ Statistical Atlas of Switzerland - Anteil Einfamilienhäuser am gesamten Gebäudebestand, 2015 accessed 18 May 2017

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office STAT-TAB - Thema 09 - Bau- und Wohnungswesen (in German) accessed 5 May 2016

- ^ Swiss Federal Statistical Office STAT-TAB Bevölkerungsentwicklung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, 1850-2000 (in German) accessed 27 April 2016

- ^ "Die Raumgliederungen der Schweiz 2016" (in German, French, Italian, and English). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 17 February 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office -Arbeitsstätten und Beschäftigte nach Gemeinde, Wirtschaftssektor und Grössenklasse accessed 31 October 2016

- ^ "Neu gegründete Unternehmen nach Gemeinde, Jahr, Wirtschaftssektor (NOGA 2008) und Variable". Stat-Tab. Swiss Federal Statistical Office. October 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Arbeitslosenquote 2011". Statistical Atlas of Switzerland. Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office - Hotellerie: Ankünfte und Logiernächte der geöffneten Betriebe accessed 31 October 2016

- ^ "18 - Öffentliche Finanzen > Steuern". Swiss Atlas. Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Statistical Department of Canton Aargau-Bereich 11 Verkehr und Nachrichtenwesen Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 21 January 2010

- ^ "Grand Casino Baden website". Archived from the original on 2007-06-24. Retrieved 2007-07-11.

- ^ Flags of the World.com Archived 2011-06-04 at the Wayback Machine accessed 28-January-2010

- ^ heisse Brunnen

- ^ Swiss inventory of cultural property of national and regional significance Archived May 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine 21.11.2008 version, (in German) accessed 28-Jan-2010

- ^ Hickley, Catherine (2023-11-08). "Amid Criticism, a Museum Says It Must Sell Its Cézannes to Survive". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-11-08.

- ^ Hickley, Catherine (2023-11-10). "Swiss Museum in Financial Straits Sells Three Cézannes for $53 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ^ ISOS site accessed 28-Jan-2010

- ^ Home page Archived 2019-06-08 at the Wayback Machine. Volksschule Baden. Retrieved on 23 April 2015. "Volksschule Baden Mellingerstrasse 19 Postfach 5401 Baden"

- ^ "Schulstufen". www.ag.ch. Canton Aargau - Department of Education, Culture and Sport. 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ "Bildung und Wissenschaft - Schulstatistiken". www.ag.ch. Canton Aargau - Department of Finance and Resources. 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- ^ a b Statistical Department of Canton Aargau - Aargauer Zahlen 2009 Archived 2012-02-22 at the Wayback Machine (in German) accessed 20 January 2010

- ^ "Nationalratswahlen 2015: Stärke der Parteien und Wahlbeteiligung nach Gemeinden" [National council elections 2015: strength of the parties and voter turnout by municipality] (in German). Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Archived from the original on 2016-08-02. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 09 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved 19 December 2018

References

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878), , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 227

- Campbell, J. Brian (2012), "Healing Waters: Rivers, Springs, Relaxation, and Health", Rivers and the Power of Ancient Rome, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, pp. 330–368, ISBN 978-0-8078-3480-0

- Hälg-Steffen, Franziska (6 November 2008a), "von Kyburg", Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in German), 19520

- de Kibourg (in French)

- von Kyburg (in Italian)

- Hälg-Steffen, Franziska (4 December 2008b), "von Lenzburg", Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in German), Bern, 19522

- de Lenzbourg (in French)

- von Lenzburg (in Italian)

- Steigmeier, Andreas (7 June 2011), "Baden (AG, comune)", Historical Dictionary of Switzerland (in Italian), Bern, 1633

- Baden (AG, Gemeinde) (in German)

- Baden (commune) (in French)

Attribution:

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Coolidge, William Augustus Brevoort (1911), "Baden (Switzerland)", in Chisholm, Hugh (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 184