Atalie Unkalunt

Atalie Unkalunt | |

|---|---|

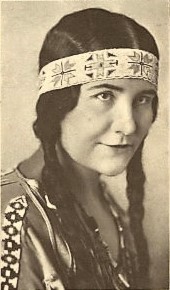

Unkalunt, 1926 | |

| Born | June 12, 1895 Stilwell, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory |

| Died | November 6, 1954 (aged 59) |

| Other names | Atalie Rider, Iva J. Rider, Iva Josephine Rider, Josie Rider |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, activist, artist, interior designer, writer |

| Years active | 1917–1951 |

| Father | Thomas LaFayette Rider |

Atalie Unkalunt (June 12, 1895 – November 6, 1954) was a Cherokee singer, interior designer, activist, and writer. Her English name Iva J. Rider appears on the final rolls of the Cherokee Nation.[1] Born in Indian Territory, she attended government-run Indian schools and then graduated from high school in Muskogee, Oklahoma. She furthered her education at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts. After a thirteen-month engagement with the YMCA as a stenographer and entertainer for World War I troops in France, she returned to the United States in 1919 and continued her music studies. By 1921, she was living in New York City and performing a mixture of operatic arias, contemporary songs, and Native music. Her attempts to become an opera performer were not successful. She was more accepted as a so-called "Indian princess", primarily singing the works of white composers involved in the Indianist movement.

Concerned with the preservation of Native American culture, Unkalunt founded the Society of the First Sons and Daughters of America in 1922. The organization allowed only tribally-affiliated Native Americans to join as full members and worked to promote Native culture and legislation which would be beneficial to Native communities. In conjunction with the society, she established a theater which featured productions written by and acted by Native people and an artists' workshop which assisted Native artists to develop and market their crafts. Among her many activities, she worked as an interior designer, wrote articles for newspapers and magazines, published a book, and researched traditional Native songs. In 1942, Unkalunt moved to Washington, D.C., and worked for the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. In the 1950s, she spent time researching Cherokee claims against the Indian Claims Commission.

Early life and education

Atalie Unkalunt, which translates from Cherokee to Sunshine Rider in English, was known as Josie Rider to her white friends.[2][3] She was born on June 12, 1895, on a farm near Stilwell, in the Going Snake District of the Cherokee Nation Indian Territory to Josephine (née Pace) and Thomas LaFayette Rider (Dom-Ges-Ke Un Ka Lunt).[4][5] Thomas was a politician and served in the first, second, and fourth Oklahoma State House of Representatives for Adair County and in the seventh and eighth state legislatures as a Senator.[6] Thomas and his children, Ola, Mary Angeline, Ruth Belle, Phoeba Montana, Mittie Earl, Roscoe Conklin, Milton Clark, Iva Josephine, Cherokee Augusta, and Anna Monetta Rider, are shown on the final Dawes Rolls for the Cherokee Nation, except the oldest and youngest, using their English names.[1][7] He was the son of Mary Ann (née Bigby) and Charles Austin Augustus Rider, who walked the Trail of Tears, and maternal grandson of Margaret Catherine (née Adair) and Thomas Wilson Bigby.[7][8] Josephine was a white woman, originally from Cherokee County, Georgia, whose family had fled Georgia during the American Civil War.[4][7][8] She was known for her singing voice, which impacted Unkalunt's choice of career.[8]

Unkalunt attended government-run Indian schools, and graduated from Central High School, in Muskogee, Oklahoma.[9][10] She then studied at the Thomas School for Girls in San Antonio, Texas, graduating in 1914.[10] In 1915, she studied piano and voice in Muskogee with Mrs. Claude L. Steele before going to Chicago to take a course in music expression.[11][12] After completing the course, she went to San Francisco and starred as the Indian female lead in a film, The Dying Race (1916), for the American Film Company.[13][14] In late 1916, she enrolled at the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, Massachusetts, studying under Millie Ryan, Clarence B. Shirley, and Charles White.[4][15] She trained in literature under Dalla Lore Sharp, at Boston University, also studying ethics, logic, and psychology; at the same time she attended the Emerson School of Oratory.[4][16] She completed her studies in 1918,[13] and then went to New York to train with the YMCA for services during World War I.[17] Stationed in France, Unkalunt worked as a secretary and entertainer for the troops for thirteen months[4][18] and sent dispatches back for the local press.[18][Notes 1]

Career

Classical music pursuits (1921–1924)

Returning stateside, Unkalunt moved to New York City in 1921, and began training with Millie Ryan.[20][21] She performed at private functions, sang on the radio, and toured throughout the country as a soprano, performing three seasons as a soloist with the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Lake Placid, New York and with Victor Herbert's orchestra.[22] Her repertoire included arias from operas, such as Carmen, Madama Butterfly, and Natoma, popular music like "Dear Eyes" by Frank H. Grey and "Thy Voice Is Like a Silver Flute" by J. H. Larway, as well as Native songs performed in costume and accompanied by a hand drum.[23] She was billed as a prima donna, an "Indian princess", and one of the foremost Native American sopranos in the country.[24] A promotional pamphlet from 1924 stated that her voice "carried the perfume of roses on the wings of song".[25] A reviewer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle said she "sang in a clear, rich voice, sympathetic and well sustained".[26]

Beginning in March 1922, and continuing until late 1923, newspaper articles reported that Unkalunt was to create the role of Nitana, in the opera of the same name, composed by Umberto Vesci, an Italian immigrant to the United States.[27] The libretto was written by Augustus Post and copyrighted in 1916.[28] According to Katie A. Callam, the first academic to write about Unkalunt's life,[29] the stereotypical story depicted a nondescript but exotic Native village, which was the home of "a noble Native warrior and an innocent Indian maiden", who became caught between the warrior and the "swaggering and paternalistic white colonizing hero".[30] After spending time in the white settlement, Nitana returned to her people in time to stop the warrior Waguntah from killing the colonist Barton and accepted the fate that the white settlers would cause the eventual demise of Native people.[31] The wide press coverage provided her career with substantial publicity and resulted in her portrait being painted by Remington Schuyler,[32] and featured on the September 1923 cover of the national magazine Farm & Fireside.[33]

For unknown reasons, the opera was not realized.[34] When Nitana fell through, Unkalunt began to write her own libretto for a Native American opera for which Herbert agreed to compose music, but the work was unfinished at his 1924 death.[34][35] After that project also failed, Unkalunt recognized that there was little chance of her singing opera in the United States.[34] Her performances were subsequently composed of Native and Indianist music, rather than opera.[36][37]

With Unkalunt's desire for Native American music to be preserved and brought to a wider audience, she had to work within the confines of public expectation and stereotypes, limiting her freedom of expression and sometimes "playing Indian" to draw in white audiences.[38][Notes 2] Native cultures were seen to be dying in the period (as in the title of Unkalunt's 1916 film) and the tendency was for white composers to apply Western harmonic systems to Native melodies in an attempt to preserve the music.[45] To be able to make a living as a performer, Unkalunt's best path as an indigenous woman was to perform these types of Indianist compositions.[46]

Ainslie scandal (1924–1928)

At the end of 1924, Unkalunt became embroiled in a lawsuit with Lucie Benedict, the daughter of the well-to-do art dealer, George H. Ainslie. Benedict alleged that Unkalunt had stolen from her father some silk material, furnishings, and clothing, originally valued at $355 but reported in court to be worn and threadbare items worth about $10. Newspapers reported that Ainslie and his wife had met the singer during a meeting of the Greenwich Village Historical Society, held in his gallery to promote Native American art. After his wife died, Ainslie befriended Unkalunt and arranged for artist friends to paint her portrait and complete a sculpture of her. When his attention became romantic, although Unkalunt refused his advances, Benedict sought to terminate her father's infatuation by accusing the singer of theft. Unkalunt testified that Ainslie was upset by her rejection and in order to hurt her backed his daughter's claims.[47][48][49]

Unkalunt was acquitted in November 1924, after Benedict admitted to planting some of the stolen items in her rooms.[50][51] Unkalunt then counter-sued Ainslie for defamation, the expenses incurred in her defense, and the loss of wages, as forty of her scheduled concerts had canceled because of the accusations.[52] She had testified at her trial that she was earning a living working as a secretary for the Tidewater Oil Company, as an assistant to a real estate agent, from writing, and from a benefactor.[48] In 1925, Ainsley won a change of venue in the case from Westchester County to Manhattan, which prompted Unkalunt to appeal the change.[53][54] The case had still not been heard in 1928, when Unkalunt filed bankruptcy declaring an unliquidated claim of $250,000 from the pending lawsuit as the majority of her available assets.[55]

Cultural preservation and activism (1921–1942)

Simultaneously with her arrival in New York City, Unkalunt began working for the New York City Board of Education. She presented songs and Native legends to over three hundred and fifty public schools between 1921 and 1923. She also lectured for the United States Department of the Interior, giving presentations on Native culture.[56] In 1922, she founded an organization known as the Society of the First Sons and Daughters of America. The society allowed only persons who were authentically Native Americans to be full members. It accepted associate members who were allies and its purpose was to foster an appreciation for cultural expression and to influence lawmaking which would be of benefit to "Amerinds",[57] a phrase Unkalunt coined to call American Indians.[56] She believed that her mixed-race status allowed her to be a bridge between two cultures, saying, "I have the strength and stoicism of the Indian, but the drive of the whites...and therefore [am] able to fight for what I want".[9]

Callam describes Unkalunt as a "one-woman force promoting Native rights, particularly related to the arts".[58] She published articles in newspapers across the country promoting Native women, and fighting against government restrictions of practicing Native religions and dance rituals.[4][58] For eight years in the 1930s she operated the Indian Council Lodge in a theater on West 58th Street.[59][60] The council was a private theater troupe, which included actors such as Chief Yowlachie and presented programs both written and performed by Native people.[4][61] The theater group was operated in conjunction with the First Sons and Daughters of America, which had a membership of nearly three thousand in 1933.[62]

Unkalunt gave lectures and sang performances to women's clubs and community organizations throughout the United States. She participated in the Wisconsin Dells Indian Pageant from 1924 to 1936 and various inter-racial music festivals. She also organized Indian Day celebrations and Native dances. She broadcast musical recitals and educational programs about Native cultures via shortwave radio to Australia, France, Germany, Great Britain, Italy, South Africa, and several locations in South America, as well as on WJZ in Newark, New Jersey and WRC in Washington, D.C.[63]

In 1929, Unkalunt and other Native performers were invited to sing at the White House for the inauguration of President Herbert Hoover and his vice president Charles Curtis, a member of the Kaw Nation. She performed again at the White House in 1934.[4][64] In her performances, Unkalunt strove to present both Indianist materials and more authentic native melodies.[65] Among songs she sang were popular works by Charles Wakefield Cadman, like "From the Land of the Sky-Blue Water" and "Her Shadow"; by Thurlow Lieurance, such as "By the Weeping Waters", "Love Song", "Lullaby", "O'er an Indian Cradle", and "Rainbow Land", among others; and by Carlos Troyer, including "A Lover's Wooing" and "Invocation to the Sun God", as well as tunes by other composers.[66] Because these works were often significantly altered to suit modern tastes, Unkalunt researched more traditional works at repositories like the Smithsonian Institution and added them to her repertoire.[67] She rarely performed Cherokee songs, which Callam speculated might have been a tactic to protect her culture.[68]

Interior designer, painter, and author (1928–1942)

In the late 1920s, Unkalunt began to make her living from interior design and by 1931, it was her primary means of making a living.[69][70] She began to explore fabric art in 1927 and a series of her designs was exhibited at the New York City Art Alliance gallery. A manufacturing company produced several silk designs and a carpet manufacturer used some of her designs to weave floor coverings, expanding her interests into interior design.[71] Unkalunt turned the second-story above her garage into a workshop to allow Native artists to produce textiles, carpets, furniture and other handicrafts.[70] She exhibited some of her artwork at Douthitt Gallery operated by John F. Douthitt and the Rehn Gallery owned by Frank Knox Morton Rehn Jr., both in New York City.[60][59]

In 1928, Unkalunt designed the offices of WMCA radio station, which occupied the entire tenth floor of the Hammerstein Theatre Building. The walls featured murals such as "Spirit of the Wind" and "The Storm Clouds", works representing flight to symbolize radio's broadcasting over air. Mirrors and furnishings also used symbols drawn from Native culture.[69] She was hired by Vice President Curtis in 1929 to decorate his private study in his suite at the Mayflower Hotel, which served as his official residence in Washington.[72][73] In 1931, she redecorated the home of Rosamund Vanderbilt, following Aztecan tribal motifs.[70]

Unkalunt published a collection of poetry and legends in The Earth Speaks, which was released in 1939.[60][74] A review in The Tennessean described that the book conveyed legends regarding the origin of the world, and various aspects of nature. She related the voices of the earth, including the wild roar of water in a river gorge, the songs of birds and buzz of insects, and music in summer breezes and falling rain.[74] William S. Gailmor, reviewing the work for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, said the book combined reality and myth to portray the magic of nature and the ability of plants, flowers, and herbs to provide both beauty and medicine. He stated that her "feeling for the earth was lyrical".[75] Historian Grant Foreman noted in his review that she had presented legends in poetic form and illustrated them with her own drawings.[76]

Later life (1942–1954)

In 1942, Unkalunt moved to Washington, D.C., at the request of Nelson Rockefeller to take up a post in the science and education department of the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs.[77][78] She continued to produce content for newspapers and magazines, sang at women's and community group gatherings, and participated in programs sponsored by the State Department for Voice of America.[79] In the early 1950s, she became interested in the work of the Indian Claims Commission and began researching in government archives to advance the work of attorneys working on Cherokee claims for breaches in treaty provisions.[80] Her organization, the First Sons and Daughters of America, continued to work on Native issues, and in 1951 had a membership of 2,400.[81]

Death and legacy

Unkalunt died on November 6, 1954, at her home at 1410 M Street NW, Washington, D.C., after a heart attack. She was buried three days later at Cedar Hill Cemetery, in nearby Suitland, Maryland. At the time of her death, she was remembered as an authority on Native American folklore.[78] In 1957, Umkalunt's nephew, Major T. L. Rider, donated a collection of her stage costumes and artifacts to the Indian Museum in Ponca City, Oklahoma. Among those items were her sand-painted piano, buckskin costumes, and beaded accessories.[59] Seventy-five images of Unkalunt, which had been donated to the C.H. Nash Museum at Chucalissa by Mrs. Dale Hall, were given by Chucalissa to the Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation in 1978.[82] The Heye collections were merged into the holdings of the Smithsonian Institution in 1990 and became part of the National Museum of the American Indian, which had been founded in 1989.[83][84] Despite her prominence in life and her connection with other noted Native performers and leaders, Unkalunt's history was not studied by academics until the 21st century.[29]

Works

- John R. Freuler (producer) (1916). The Dying Race (Motion picture). San Francisco, California: American Film Company.[13][14]

- [Unkalunt], Princess Atalie (May 22, 1929). Land of the Sky Blue Water (10-inch recording). Camden, New Jersey: Victor Talking Machine Company. BVE-Test-644.[85]

- [Unkalunt], Princess Atalie (May 22, 1929). Navajo Drinking Song (10-inch recording). Camden, New Jersey: Victor Talking Machine Company. BVE-Test-645.[85]

- [Unkalunt], Princess Atalie (1939). The Earth Speaks. New York, New York: Fleming H. Revell Company. OCLC 34883152.

- [Unkalunt], Princess Atalie (1950). Talking Leaves. New York, New York: unpublished manuscript.[4]

- Unkalunt, Atalie (1954). "Forward". In Hirsh, Alice (ed.). From Pipes Long Cold. Boston, Massachusetts: Bruce Humphries, Inc. OCLC 13242675.[4]

Notes

- ^ Ewen & Wolklock state she joined in 1917 and served for eighteen months abroad.[4] However newspapers confirm she was abroad only thirteen months from October 1918 to November 1919.[17][18] Callam noted that because she could not pay her own expenses as entertainers were expected to do, Unkalunt was officially a stenographer for the business unit of the YMCA and had to falsify her birth date to meet the 25-year-age requirement for service.[19]

- ^ Playing Indian is a term which defines racist entertainment depicting people of Native American descent in stereotypical ways. It is similar to minstrelsy, which made caricatures of African Americans.[39] It can describe white people who have misappropriated Native culture and symbolism, as is described in Philip J. Deloria's Playing Indian.[40][41] It can also describe actual Native performers, who were forced to modify their performances to be acceptable to white audiences.[2] For example, Native women were expected to perform as princesses in buckskin dresses and be adorned with beaded accessories, while males were portrayed as chiefs wearing feathered headdresses and fringed buckskins and often spoke in broken English or were stoically silent.[42][43][44]

References

Citations

- ^ a b Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes 1981, p. 370.

- ^ a b Callam 2020, p. 92.

- ^ Muskogee Times-Democrat 1923, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ewen & Wollock 2015, p. 367.

- ^ The Chronicles of Oklahoma 1932, p. 612.

- ^ Starr 1921, pp. 658–659.

- ^ a b c Starr 1921, p. 658.

- ^ a b c Callam 2020, p. 93.

- ^ a b Callam 2020, p. 94.

- ^ a b Muskogee Times-Democrat 1914, p. 5.

- ^ Adair County Republican 1915, p. 4.

- ^ Muskogee Times-Democrat 1915, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Lardy 1918, p. 22.

- ^ a b Chicago Historical Society 2008.

- ^ Muskogee Times-Democrat 1916, p. 5.

- ^ The Standard Sentinel 1918a, p. 2.

- ^ a b The Standard Sentinel 1918b, p. 8.

- ^ a b c The Standard Sentinel 1919, p. 2.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 96.

- ^ The Adair County Democrat 1921, p. 1.

- ^ The Evening News 1922, p. 8.

- ^ Ewen & Wollock 2015, p. 367; The Adair County Democrat 1921, p. 1; The Evening News 1922, p. 8; The Adair County Democrat 1927, p. 1; The Ponca City News 1959, p. 2.

- ^ Muskogee Times-Democrat 1921, p. 4.

- ^ Ewen & Wollock 2015, p. 367; The Pawhuska Daily Journal 1925, p. 7; The Morning Call 1945, p. 15; Callam 2020, p. 112.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 89.

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1938, p. 17.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 109, 113.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 112.

- ^ a b Callam 2020, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 114.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 121.

- ^ a b c Callam 2020, p. 122.

- ^ The Adair County Democrat 1927, p. 1.

- ^ The Daily Record 1926, p. 3.

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1926, p. 7.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 18–19, 92.

- ^ Melnick 2000, p. 31.

- ^ Melnick 2000, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Faragher 2000, pp. 279–280.

- ^ Lomawaima 2016, p. 258.

- ^ Bold 2022, p. 84.

- ^ Baird 2003, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 25.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 89–91.

- ^ Detroit Free Press 1924, p. 63.

- ^ a b The New York Times 1924a, p. 25.

- ^ The New York Times 1924b, p. 25.

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1924, p. 2.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 127.

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1925, pp. 1, 5.

- ^ The Yonkers Statesman 1925, p. 2.

- ^ The Daily News 1925, p. 14.

- ^ The New York Evening Post 1928, p. 1.

- ^ a b Callam 2020, p. 97.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 145.

- ^ a b Callam 2020, p. 98.

- ^ a b c The Ponca City News 1959, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Callam 2020, p. 99.

- ^ The Oswego Palladium-Times 1932, p. 2.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 125.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 99, 107–108.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 98, 103.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 100.

- ^ Callam 2020, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 102.

- ^ Callam 2020, p. 104.

- ^ a b The Morning Call 1928, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Baron 1931, p. 3.

- ^ McCann 1929, p. 12E.

- ^ McCann 1929, p. 13.

- ^ The Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1929, p. 12E.

- ^ a b The Tennessean 1940, p. 20.

- ^ Gailmor 1940, p. 49.

- ^ Foreman 1940, p. 396.

- ^ Tix 1942, p. 57.

- ^ a b The Washington Post and Times Herald 1954, p. 20, column 4.

- ^ The Morning Call 1945, p. 15; The Evening Star 1949, p. 28; King 1951, p. 14; The Sunday News 1951, p. 49.

- ^ King 1951, p. 14.

- ^ The Evening Star 1951, p. 6.

- ^ Menyuk & Galban 2017.

- ^ O'Neal & Menyuk 2011.

- ^ Deloria 2018, p. 106.

- ^ a b Callam 2020, p. 105.

Bibliography

- Baird, Robert (2003). "Indian Leaders". In Rollins, Peter C. (ed.). The Columbia Companion to American History on Film: How the Movies Have Portrayed the American Past. New York, New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 161–168. ISBN 978-0-231-50839-1.

- Baron, Mark (June 22, 1931). "A New Yorker at Large". The Billings Gazette. Billings, Montana. p. 3. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bold, Christine (2022). 'Vaudeville Indians' on Global Circuits, 1880s–1930s. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-26490-6.

- Callam, Katie A. (April 2020). 'To Look After and Preserve': Curating the American Musical Past, 1905-1945 (PhD). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Retrieved August 6, 2022.

- Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes (1981). Index to the Final Rolls of Citizens and Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes in Indian Territory. Vol. 2: Cherokees by Blood: (Ice, Lewis)-Seminoles by Blood and Freedmen. Washington, D. C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. OCLC 9619071.

- Deloria, Philip J. (Spring 2018). "The New World of the Indigenous Museum". Daedalus. 147 (2). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press for the American Academy of Arts and Sciences: 106–115. doi:10.1162/DAED_a_00494. ISSN 0011-5266. JSTOR 48563023. OCLC 7358628062. S2CID 57571590. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- Ewen, Alexander; Wollock, Jeffrey (2015). "Rider, Iva Josephine (Princess Atalie Unkalunt, "Sunshine Rider") (1895–1954)". Encyclopedia of the American Indian in the twentieth century (First ed.). Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-8263-5595-9.

- Faragher, John Mack (May 2000). "Book Review: Playing Indian by Philip J. Deloria". Pacific Historical Review. 69 (2). Berkeley, California: University of California Press: 279–280. doi:10.2307/3641443. ISSN 0030-8684. JSTOR 3641443. OCLC 5972226858. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- Foreman, Grant (December 1940). "Book Reviews: The Earth Speaks by Princess Atalie; pp. 223 (New York, 1939.)". Chronicles of Oklahoma. XVIII (4). Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Oklahoma Historical Society: 396. ISSN 0009-6024. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- Gailmor, William S. (April 28, 1940). "Sorcery of Nature Caught by Indian". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. p. 49. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- King, John M. (October 12, 1951). "Noted Cherokee Leader Serves Her People". The Sequoyah County Times. Sallisaw, Oklahoma. p. 14. Retrieved August 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- Lardy, Augustin (May 19, 1918). "A Real Cherokee Indian Girl in Boston". Sunday Magazine. Boston, Massachusetts: The Boston Post. p. 22. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- Lomawaima, K. Tsianina (Summer 2016). "A Principle of Relativity through Indigenous Biography". Indigenous Conversations About Biography. 39 (3). Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press: 248–269. ISSN 0162-4962. JSTOR 26405098. OCLC 6909709713. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- McBride, Bunny (1997). Molly Spotted Elk: A Penobscot in Paris. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2756-9.

- McCann, Annabel Parker (April 21, 1929). "Indian Princess to Decorate Vice President's Apartment". The Washington Post. No. 19302. Washington, D.C. p. 13. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- Melnick, Jeffrey (Fall 2000). "Book Review: Playing Indian by Philip J. Deloria". The Radical Teacher (58). Brooklyn, New York: Center for Critical Education, Inc.: 31–32. ISSN 0191-4847. JSTOR 20710052. OCLC 5542767162. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- Menyuk, Rachel; Galban, Maria (2017). "Photographs of Princess Atalie Unkalunt Collection". Smithsonian Online Virtual Archives. Suitland, Maryland: National Museum of the American Indian. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- O'Neal, Jennifer; Menyuk, Rachel (2011). "Museum of the American Indian/Heye Foundation Records, 1890–1989". sova.si. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on March 9, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- Starr, Emmet (1921). "Rider, Thomas L.". History of the Cherokee Indians and Their Legends and Folk Lore. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: The Warden Company. pp. 658–659. OCLC 2702462.

- Tix, Polly (October 11, 1942). "Oklahoma Has Another Celebrated Name in Washington". The Oklahoman. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. p. 57. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Ainslie 'Princess' Repudiates Title" (PDF). The New York Times. New York, New York. November 11, 1924. p. 25. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Air Force Officer Visiting Here after Newfoundland Duty Tour". The Ponca City News. Ponca City, Oklahoma. April 17, 1959. p. 2. Retrieved August 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Artist Lists Suit As Bankrupt Asset" (PDF). The New York Evening Post. New York, New York. September 6, 1928. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "A Stilwell Princess Sings on Steel Pier". The Adair County Democrat. Stilwell, Oklahoma. September 15, 1927. p. 1. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Cherokee Prima Donna to Give Recital". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. February 6, 1926. p. 7. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Curtis Remains Democratic, Though He and Ganns Occupy Capital Hotel's Royal Suite" (PDF). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. June 16, 1929. p. 11E, 12E. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Delights Boston Audience". The Standard Sentinel. Stilwell, Oklahoma. May 16, 1918. p. 2. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Former Oswego Woman Is Author of Indian Opera" (PDF). The Oswego Palladium-Times. Oswego, New York. February 18, 1932. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Gets Change of Venue". The Yonkers Statesman. Yonkers, New York. March 25, 1925. p. 2. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Give Outdoor Play at Jane Elkus Camp". The Daily Record. Long Branch, New Jersey. July 27, 1926. p. 3. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Harrisburgers Have Part in Today's Radio Concert". The Evening News. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. July 3, 1922. p. 8. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Indian Legends". The Tennessean. Nashville, Tennessee. June 2, 1940. p. 20. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Indians Thank Truman for Reburial Gesture". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. September 2, 1951. p. 6. Retrieved August 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Iva J. Rider". The Adair County Democrat. Stilwell, Oklahoma. February 10, 1921. p. 1. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "John Rudolph Freuler papers, 1910–1955". CHS Media. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Historical Society. 2008. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- "Luncheon to Have Indonesian Theme". The Evening Star. Washington, D.C. February 23, 1949. p. 28. Retrieved September 22, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Miss Atalie Rider". The Washington Post and Times Herald. Washington, D.C. November 8, 1954. p. 20, column 4. Retrieved August 7, 2022.

- "Miss Iva J. Rider". Adair County Republican. Bunch, Oklahoma. May 28, 1915. p. 4. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Miss Iva J. Rider". The Standard Sentinel. Stilwell, Oklahoma. October 24, 1918. p. 8. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Miss Iva J. Rider". The Standard Sentinel. Stilwell, Oklahoma. November 16, 1919. p. 4. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Miss Iva Rider". Muskogee Times-Democrat. Muskogee, Oklahoma. March 9, 1915. p. 5. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Miss Rider to Graduate". Muskogee Times-Democrat. Muskogee, Oklahoma. May 4, 1914. p. 5. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Mrs. Claude L. Steele". Muskogee Times-Democrat. Muskogee, Oklahoma. October 23, 1916. p. 5. Retrieved August 5, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Muskogee Maiden Annexes Fame in New York Music". Muskogee Times-Democrat. Muskogee, Oklahoma. January 20, 1921. p. 4. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Prefers To Be Plain 'Josie'". Muskogee Times-Democrat. Muskogee, Oklahoma. February 13, 1923. p. 5. Retrieved August 7, 2022 – via Newspaperarchive.com.

- "Princess Atalie Is Woman of Talents". The Pawhuska Daily Journal. Pawhuska, Oklahoma. April 6, 1925. p. 7. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Princess Atalie Unkalunt" (PDF). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. May 11, 1938. p. 17. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Princess Atalie Unkalunt: Indian Soprano". The Morning Call. Paterson, New Jersey. April 20, 1945. p. 15. Retrieved August 6, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Princess Atalie Unkalunt Sues Ainslee for $250,000 for 'Destroying Good Name'". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. February 22, 1925. pp. 1, 5. Retrieved August 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "'Princess' Freed of Ainslie Charges; Cheers for Towns". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. November 15, 1924. p. 2. Retrieved August 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Princess to Appeal Venue Change in Her $250,000 Suit". The Daily News. New York, New York. April 3, 1925. p. 14. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Says Mrs. Benedict Detested 'Princess'" (PDF). The New York Times. New York, New York. November 14, 1924. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2022. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Thomas Lafayette Rider". The Chronicles of Oklahoma. 10 (4). Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Oklahoma Historical Society: 612. December 1932. ISSN 0009-6024. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- "Totzauer to Present 15 in Student Recital Today at Studio". The Sunday News. Ridgewood, New Jersey. May 20, 1951. p. 49. Retrieved August 9, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Wealthy Mr. Ainslie's Surprising Change of Heart". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. December 7, 1924. p. 63. Retrieved August 7, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- "WMCA Studios in Broadway Quarters". The Morning Call. Allentown, Pennsylvania. December 29, 1928. p. 20. Retrieved August 8, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.