Streamline Moderne

Top: San Francisco Maritime Museum (1937) Middle: New York Central Hudson locomotive (1939): Bottom: Blytheville Greyhound Bus Station, Arkansas (1937) | |

| Years active | 1930s–1940s |

|---|---|

| Location | International |

Streamline Moderne is an international style of Art Deco architecture and design that emerged in the 1930s. Inspired by aerodynamic design, it emphasized curving forms, long horizontal lines, and sometimes nautical elements. In industrial design, it was used in railroad locomotives, telephones, buses, appliances, and other devices to give the impression of sleekness and modernity.[1]

In France, it was called the style paquebot, or "ocean liner style", and was influenced by the design of the luxury ocean liner SS Normandie, launched in 1932.

Influences and origins

As the Great Depression of the 1930s progressed, Americans saw a new aspect of Art Deco, i.e., streamlining, a concept first conceived by industrial designers who stripped Art Deco design of its ornament in favor of the aerodynamic pure-line concept of motion and speed developed from scientific thinking. The cylindrical forms and long horizontal windowing in architecture may also have been influenced by constructivism, and by the New Objectivity artists, a movement connected to the German Werkbund. Examples of this style include the 1923 Mossehaus, the reconstruction of the corner of a Berlin office building in 1923 by Erich Mendelsohn and Richard Neutra. The Streamline Moderne was sometimes a reflection of austere economic times; sharp angles were replaced with simple, aerodynamic curves, and ornament was replaced with smooth concrete and glass.

The style was the first to incorporate electric light into architectural structure. In the first-class dining room of the SS Normandie, fitted out 1933–35, twelve tall pillars of Lalique glass, and 38 columns lit from within illuminated the room. The Strand Palace Hotel foyer (1930), preserved from demolition by the Victoria and Albert Museum during 1969, was one of the first uses of internally lit architectural glass, and coincidentally was the first Moderne interior preserved in a museum.

Architecture

Streamline Moderne appeared most often in buildings related to transportation and movement, such as bus and train stations, airport terminals, roadside cafes, and port buildings.[2] It had characteristics common with modern architecture, including a horizontal orientation, rounded corners, the use of glass brick walls or porthole windows, flat roofs, chrome-plated hardware, and horizontal grooves or lines in the walls. They were frequently white or in subdued pastel colors.

An example of this style is the Aquatic Park Bathhouse in the Aquatic Park Historic District, in San Francisco. Built beginning in 1936 by the Works Progress Administration, it features the distinctive horizontal lines, classic rounded corners railing and windows of the style, resembling the elements of ship. The interior preserves much of the original decoration and detail, including murals by artist and color theoretician Hilaire Hiler. The architects were William Mooser Jr. and William Mooser III. It is now the administrative center of Aquatic Park Historic District.

The Normandie Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico, which opened during 1942, is built in the stylized shape of the ocean liner SS Normandie, and displays the ship's original sign. The Sterling Streamliner Diners in New England were diners designed like streamlined trains.

Another example is Hollywood, California's Julian Medical Building, which has been described as a "landmark",[3] "an architectural masterpiece",[4] and "one of the crowning achievements of Streamline Moderne."[5] The building's distinctive features include a rounded Moderne corner, windswept tower, and pylon-separated horizontally-reinforced windows.[3][6]

Although Streamline Moderne houses are less common than streamline commercial buildings, residences do exist. The Lydecker House in Los Angeles, built by Howard Lydecker, is an example of Streamline Moderne design in residential architecture. In tract development, elements of the style were sometimes used as a variation in postwar row housing in San Francisco's Sunset District.

- Aquatic Park Bathhouse, now part of the Aquatic Park Historic District San Francisco (1936)

- Coca-Cola factory in Los Angeles by Robert V. Derrah (1936)

- East Finchley Tube station, London (1937)

- Hecht Company Warehouse in northeast Washington, D.C. (1937)

- Pan-Pacific Auditorium in Los Angeles, California (1935–1989)

- Marine Air Terminal of LaGuardia Airport, New York (1939)

- Hotel Shangri-La (1939), Santa Monica, California

- Greyhound Bus Station, Columbia, South Carolina (1936–1939)

- The Las Vegas Union Pacific Railroad station (mid-1930s, demolished 1971)

- Streamline Moderne church, First Church of Deliverance, Chicago, Illinois (1939), by Walter T. Bailey. Towers added 1948.

- Long Beach, CA

Paquebot style

In France, the style was called Paquebot, meaning ocean liner. The French version was inspired by the launch of the ocean liner Normandie in 1935, which featured an Art Deco dining room with columns of Lalique crystal. Buildings using variants of the style appeared in Belgium and in Paris, notably in a building at 3 boulevard Victor in the 15th arrondissement, by the architect Pierre Patout. He was one of the founders of the Art Deco style. He designed the entrance to the Pavilion of a Collector at the 1925 Exposition of Decorative Arts, the birthplace of the style. He was also the designer of the interiors of three ocean liners, the Ile-de-France (1926), the L'Atlantique (1930), and the Normandie (1935).[7] Patout's building on Avenue Victor lacked the curving lines of the American version of the style, but it had a narrow "bow" at one end, where the site was narrow, long balconies like the decks of a ship, and a row of projections like smokestacks on the roof. Another 1935 Paris apartment building at 1 Avenue Paul Doumer in the 16th arrondissement had a series of terraces modelled after the decks of an ocean liner.[8]

The Flagey Building was built on the Place Flagey in Ixelles (Brussels), Belgium, in 1938, in the paquebot style,[9] and has been nicknamed "Packet Boat"[10] or "paquebot".[11] It was designed by Joseph Diongre, and selected as the winning design in an architectural competition[12] to create a building to house the former headquarters of the Belgian National Institute of Radio Broadcasting (INR/NIR).[13] The building was extensively renovated, and in 2002, it reopened as a cultural centre known as Le Flagey.[12][14]

- Main dining room of the ocean liner S.S. Normandie by Pierre Patout (1935)

- Paquebot building at 3 boulevard Victor, 15th arrondissement, Paris by Patout (1935)

- Flagey Building (or Maison de la Radio), Ixelles (Brussels), Belgium (1938)

Automobiles

The defining event for streamline moderne design in the United States was the 1933–34 Chicago World's Fair, which introduced the style to the general public. The new automobiles adapted the smooth lines of ocean liners and airships, giving the impression of efficiency, dynamism, and speed. The grills and windshields tilted backwards, cars sat lower and wider, and they featured smooth curves and horizontal speed lines. Examples include the 1934 Chrysler Airflow and the 1934 Studebaker Land Cruiser. The cars also featured new materials, including bakelite plastic, formica, Vitrolight opaque glass, stainless steel, and enamel, which gave the appearance of newness and sleekness.[15]

Other later examples include the 1950 Nash Ambassador "Airflyte" sedan with its distinctive low fender lines, as well as Hudson's postwar cars, such as the Commodore,[16] that "were distinctive streamliners—ponderous, massive automobiles with a style all their own".[17]

- The Rumpler Tropfenwagen (1921) was designed by Edmund Rumpler, who was initially an aircraft designer

- The 1931 WIKOV Supersport, Prostějov Moravia was one of the first produced truly aerodynamically designed automobiles.

- The 1933 Pierce Silver Arrow

- The 1934 Tatra 77 was one of the first serial-produced truly aerodynamically designed automobiles.

- 1934 Chrysler Airflow

- Studebaker Land Cruiser (1934)

- Stout Scarab (1935) on display at Houston Fine Arts Museum

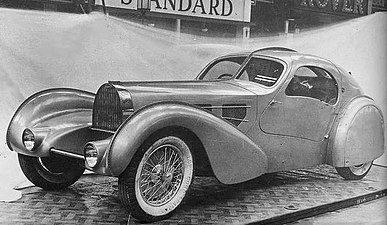

- Bugatti Aérolithe (1936)

- 1937 Cord Automobile

- Talbot Teardrop SS 150 (1938)

- 1939 Schlörwagen - Subsequent wind tunnel tests yielded a drag coefficient of 0.113

- 1939 Dodge 'Job Rated' streamline model truck

- 1946 Chevrolet DP ½-ton 'Art Deco' pickup

Planes, boats and trains

Streamlining became a widespread design practice for aircraft, railroad locomotives, and ships.

- MV Kalakala, the first streamlined ferry boat (1935)

- Hamburg Flyer (1932)

- Diesel III, the Netherlands (1934)

- DRG Class 05 (1935), world speed record for steam locomotives in 1936

- Mercury locomotive designed by Henry Dreyfuss (1936)

- Duchess of Hamilton locomotive (1938)

- Chicago PCC car

- 1936 M 290.0 Slovenská Strela speed train, Czechoslovakia. Slovenská strela was manufactured by Tatra Kopřivnice in Moravia in 1936 for Czechoslovak State Railways.

Industrial design

Streamline style can be contrasted with functionalism, which was a leading design style in Europe at the same time. One reason for the simple designs in functionalism was to lower the production costs of the items, making them affordable to the large European working class.[18] Streamlining and functionalism represent two different schools in modernistic industrial design.

- The first bakelite telephone (1931)

- Philips Art Deco radio set (1931)

- Electrolux Vacuum cleaner (1937)

- Streamlined toaster

- Streamlined Bakelite radio (1952)

Other notable examples

- 1923 Mossehaus, Berlin. Reconstruction by Erich Mendelsohn and Richard Neutra

- 1926: Long Beach Airport Main Terminal, Long Beach, California

- 1928: Lockheed Vega, designed by John Knudsen Northrop, a six-passenger, single-engine aircraft used by Amelia Earhart

- 1928: Doctor's Building in Kyiv, Ukraine

- 1928–1930: Canada Permanent Trust Building in Toronto

- 1930: Strand Palace Hotel, London; foyer designed by Oliver Percy Bernard

- 1930–1934: Broadway Mansions, Shanghai, designed by B. Flazer of Palmer and Turner

- 1931: The Eaton's Seventh Floor in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, designed by Jacques Carlu, in the former Eaton's department store

- 1931: Napier, New Zealand, rebuilt in Art Deco and Streamline Moderne styles after a major earthquake

- 1931–1932: Plärrer Automat, Nuremberg, Bavaria, Germany by later Nazi-collaborate architect Walter Brugmann

- 1931–1933: Hamilton GO Centre, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada by Alfred T. Fellheimer

- 1931–1944: Serralves House, Porto, Portugal, designed by José Marques da Silva

- 1932: Edifício Columbus, São Paulo, Brazil (demolished 1971)

- 1932: Arnos Grove Tube Station, London, England, designed by Charles Holden

- 1933: Casa della Gioventù del Littorio, Rome, designed by Luigi Moretti

- 1933: Ty Kodak building in Quimper, France, designed by Olier Mordrel

- 1933: Southgate tube station, London

- 1933: Burnham Beeches in Sherbrooke, Victoria, Australia. Harry Norris architect

- 1933: Merle Norman Building, Santa Monica, California See also History of Santa Monica, California

- 1933: Midland Hotel, Morecambe, England

- 1933: Edificio Lapido, Montevideo, Uruguay

- 1933–1940: Interior of Chicago's Museum of Science and Industry, designed by Alfred Shaw

- 1934: Pioneer Zephyr, the first of Edward G. Budd's streamlined stainless-steel locomotives

- 1934: Tatra 77, the first mass-market streamline automotive design

- 1934: Chrysler Airflow, the second mass-market streamline automotive design

- 1934: Hotel Shangri-La in Santa Monica, California

- 1934: Edifício Nicolau Schiesser, São Paulo, Brazil (demolished 2014)

- 1935: Ford Building in Balboa Park, San Diego, California

- 1935: The De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill-on-Sea, England

- 1935: Pan-Pacific Auditorium, Los Angeles

- 1935: Edificio Internacional de Capitalización, Mexico City, Mexico

- 1935: The Hindenburg, Zeppelin passenger accommodations

- 1935: Interior of Lansdowne House on Berkeley Square in Mayfair, London

- 1935: The Hamilton Hydro-Electric System Building, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada

- 1935: MV Kalakala, the world's first streamlined ferry

- 1935: Lee Drug, Hollywood, California, designed by B.D. Bixby[3]

- 1935: Technologist's Building in Kyiv, Ukraine

- 1935–1938: Former Belgian National Institute of Radio Broadcasting (known as the Maison de la Radio) on Eugène Flagey Square in Ixelles (Brussels), by Joseph Diongre

- 1935–1956: High Tower Court, Hollywood Heights, Los Angeles[19]

- 1936: Lasipalatsi, in Helsinki, Finland, functionalist office building and now a cultural and media center

- 1936: Florin Court, on Charterhouse Square in London, built by Guy Morgan and Partners

- 1936: Campana Factory, historic factory in Batavia, Illinois

- 1936: Edifício Guarani, São Paulo, Brazil

- 1936: Nordic Theater, Marquette, Michigan

- 1936: Alkira House, Melbourne

- 1936: Longford Cinema, Manchester, England (closed since 1995)

- 1937: Earls Court Exhibition Centre, London

- 1937: Earl's Court tube station, London, facing the Earls Court Exhibition frontage

- 1937: Blytheville Greyhound Bus Station in Blytheville, Arkansas

- 1937: Regent Court, residential apartments on Bradfield Road, Hillsborough, Sheffield

- 1937: Malloch Building, residential apartments at 1360 Montgomery Street in San Francisco

- 1937: B B Chemical Company, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, built by Coolidge, Shepley, Bulfinch & Abbott

- 1937: Belgium Pavilion, at the Exposition Internationale, Paris

- 1937: TAV Studios (Brenemen's Restaurant), Hollywood

- 1937: Dudley Zoo, Dudley, UK

- 1937: Hecht Company Warehouse in Washington, D.C.

- 1937: Minerva (or Metro) Theatre and the Minerva Building, Potts Point, New South Wales, Australia

- 1937: Bather's Building in the Aquatic Park Historic District, now the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park Maritime Museum

- 1937: Barnum Hall (High School auditorium), Santa Monica, California

- 1937: J.W. Knapp Company Building (department store) Lansing, Michigan

- 1937: Wan Chai Market, Wan Chai, Hong Kong

- 1937: River Oaks Shopping Center, Houston

- 1937: Toronto Stock Exchange Building, mix of Art Deco and Streamline Moderne

- 1937: Pittsburgh Plate Glass Enamel Plant, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, by Alexander C. Eschweiler

- 1937: Old Greyhound Bus Station (Jackson, Mississippi)

- 1937: Gramercy Theatre, New York City

- 1937: Gdynia Maritime University in Poland, by Bohdan Damięcki

- 1938: Esslinger Building in San Juan Capistrano, California

- 1938: Fife Ice Arena in Kirkcaldy, United Kingdom

- 1938: Mark Keppel High School, Alhambra, California

- 1938: Greyhound Bus Terminal (Evansville, Indiana)

- 1938: 20th Century Limited, New York City

- 1938: Jones Dog & Cat Hospital, West Hollywood, California, by Wurdeman & Beckett (remodel of 1928 original construction)[20]

- 1938: Greyhound Bus Depot (Columbia, South Carolina)

- 1938: Marine Court, St Leonards, East Sussex, England

- 1939: Bartlesville High School, Bartlesville, Oklahoma

- 1939: First Church of Deliverance in Chicago, Illinois

- 1939: Marine Air Terminal, LaGuardia Airport, New York City

- 1939: Road Island Diner, Oakley, Utah

- 1939: Albion Hotel, South Beach, Miami Beach, Florida

- 1939: Pavilions at the 1939 New York World's Fair

- 1939: Regal Shoes Building, Hollywood, California, designed by Walker & Eisen[3]

- 1939: Department of Water and Power Building, Los Angeles, California[21]

- 1939: Boots Court Motel in Carthage, Missouri

- 1939: Cardozo Hotel, Ocean Drive, South Beach, Miami Beach, Florida

- 1939: Daily Express Building, Manchester, England

- 1939: East Finchley tube station, London, England

- 1939: Appleby Lodge, Manchester, England

- 1939: Philharmonic Hall, Liverpool, England

- 1939–1940: Interior of Coffman Memorial Union, Minneapolis, Minnesota (renovated 1976, restored 2003)

- 1940: Gabel Kuro jukebox designed by Brooks Stevens

- 1940: Ann Arbor Bus Depot, Michigan

- 1940: Jai Alai Building, Taft Avenue Manila, Philippines (demolished 2000)

- 1940: Hollywood Palladium, Los Angeles, California

- 1940: Las Vegas Union Pacific Station, Las Vegas, Nevada

- 1940: Rivoli Cinemas, 200 Camberwell Road Hawthorn East, Melbourne, Australia

- 1940: Pacaembu Stadium, São Paulo, Brazil

- 1941: Avalon Hotel, Ocean Drive, South Beach, Miami Beach, Florida

- 1942: Coral Court Motel in Marlborough, Missouri

- 1942: Normandie Hotel in San Juan, Puerto Rico

- 1942: Mercantile National Bank Building in Dallas, Texas

- 1942: Musick Memorial Radio Station in Auckland, New Zealand

- 1943: Edifício Trussardi in São Paulo, Brazil

- 1944: Huntridge Theater, Las Vegas, Nevada

- 1945: Muscats Motors, Gżira, Malta

- 1945: Ressano Garcia Railway Station, Mozambique

- 1946: Gerry Building, Los Angeles, California

- 1946: Canada Dry Bottling Plant, Silver Spring, Maryland

- 1946: Broadway Theatre, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada

- 1949: Sault Memorial Gardens, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario

- 1949: Beacon Lodge, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada

- 1951: Federal Reserve Bank Building, Seattle, Washington

- 1954: Poitiers Theater designed by Edouard Lardillier

- 1955: Eight Forty One (former Prudential Life Insurance Building), Jacksonville, Florida, designed by KBJ Architects

- 1957: Edinburgh Place Ferry Pier (Star Ferry Pier, Central), Hong Kong (demolished 2006)

- 1957: Tsim Sha Tsui Ferry Pier, Hong Kong

- 1965: Hung Hom Ferry Pier, Hong Kong

- 1968: Wan Chai Pier, Hong Kong (demolished 2014)

In motion pictures

- Tanks, aircraft and buildings in William Cameron Menzies's 1936 movie Things to Come

- The buildings in Frank Capra's 1937 movie Lost Horizon, designed by Stephen Goosson

- The design of the "Emerald City" in the 1939 movie The Wizard of Oz

- The main character's helmet and rocket pack in the 1991 movie The Rocketeer

- The High Tower apartments, featured in the 1973 film The Long Goodbye and 1991 film Dead Again[19]

- The Malloch Apartment Building at 1360 Montgomery St, San Francisco that serves as apartment for Lauren Bacall's character in Dark Passage

See also

- Century of Progress Chicago's second World's Fair (1933–34)

- Constructivist architecture

- Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne (1937) (1937 Paris Exposition)

- Googie architecture

- PWA Moderne – a Moderne style in the United States completed between 1933 and 1944 as part of relief projects sponsored by the Public Works Administration (PWA) and the Works Progress Administration (WPA)

- Raygun Gothic

- Streamliner

References

- ^ "A true example of Streamline Moderne". Times of Malta. 6 September 2012. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016.

- ^ Bridge, Nicole. Architecture 101, Simon & Schuster, New York, (2015), page 203.

- ^ a b c d "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment District". United States Department of the Interior - National Park Service. April 4, 1985.

- ^ Winter, Robert (2009). An Architectural Guidebook to Los Angeles. Gibbs Smith. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-4236-0893-6.

- ^ "Owl Drug/Julian Medical - Hollywood Historic Site". Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Oudin, Bernard. Dictionnaire des Architectes, Sechiers, Paris, (1994), (in French), page 372.

- ^ Texier, Simon (2012), Paris Panorama of Architecture, Parigramme, p. 142, ISBN 9782840966678

- ^ "Le Flagey - Découvrez Bruxelles en musique". Bruxelles ma Belle (in French). 16 November 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "New course for packet boat". SVR-Architects. 14 July 2002. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Februari 2017: Flagey architectuurwandeling en pianoconcert". Antwerpencultuurstad (in Dutch). 17 February 2017. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ a b "The Flagey Building". Flagey. Retrieved 8 May 2021.

- ^ "Flagey". jazz.brussels. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ "Flagey N.V." SVR-Architects. 17 October 2002. Retrieved 9 May 2021.

- ^ McCourt, Mark, "When Art Deco is Really Streamline Moderne", Hemmings Daily, 29 May 2014

- ^ "1948 Hudson Models – Tech Pages Article". Auto History Preservation Society. Retrieved February 14, 2018.

- ^ Reed, Robert C. (1975). The Streamline Era. San Marino, California: Golden West Books. ISBN 0-87095-053-3.

- ^ Nickelsen, Trine (15 June 2010). "Aluminium – en kulturhistorie" (in Norwegian). Apollon. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ a b Bettsky, Aaron (15 July 1993). "A Hollywood Ending for Those Who Take This Elevator to the Top". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ Bos, Sascha (16 July 2014). "Historic 1938 Building Could Complicate Massive WeHo Development". LA Weekly. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Lankershim Arts Center". City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs. Retrieved September 18, 2024.