Armistice of 11 November 1918

The Armistice of 11 November 1918 was the armistice signed at Le Francport near Compiègne that ended fighting on land, at sea, and in the air in World War I between the Entente and their last remaining opponent, Germany. Previous armistices had been agreed with Bulgaria, the Ottoman Empire and Austria-Hungary. It was concluded after the German government sent a message to American president Woodrow Wilson to negotiate terms on the basis of a recent speech of his and the earlier declared "Fourteen Points", which later became the basis of the German surrender at the Paris Peace Conference, which took place the following year.

Also known as the Armistice of Compiègne (French: Armistice de Compiègne, German: Waffenstillstand von Compiègne) from the place where it was officially signed at 5:45 a.m. by the Allied Supreme Commander, French Marshal Ferdinand Foch,[1] it came into force at 11:00 a.m. Central European Time (CET) on 11 November 1918 and marked a victory for the Entente and a defeat for Germany, although not formally a surrender.

The actual terms, which were largely written by Foch, included the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front, the withdrawal of German forces from west of the Rhine, Entente occupation of the Rhineland and bridgeheads further east, the preservation of infrastructure, the surrender of aircraft, warships, and military materiel, the release of Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians, eventual reparations, no release of German prisoners and no relaxation of the naval blockade of Germany. The armistice was extended three times while negotiations continued on a peace treaty. The Treaty of Versailles, which was officially signed on 28 June 1919, took effect on 10 January 1920.

Fighting continued up until 11 a.m. CET on 11 November 1918, with 2,738 men dying on the last day of the war.[2]

Background

Deteriorating situation for the Germans

The military situation for the Central Powers had been deteriorating rapidly since the Battle of Amiens at the beginning of August 1918, which precipitated a German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line and loss of the gains of the German spring offensive.[3] The Allied advance, later known as the Hundred Days Offensive, entered a new stage on 28 September, when a massive United States and French attack opened the Meuse–Argonne offensive, while to the north, the British were poised to assault at the St Quentin Canal, threatening a giant pincer movement.[4]

Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire was close to exhaustion, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was in chaos, and on the Macedonian front, resistance by the Bulgarian Army had collapsed, leading to the Armistice of Salonica on 29 September.[5] With the collapse of Bulgaria, and Italian victory in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, the road was open to an invasion of Germany from the south via Austria.[6] In Germany, chronic food shortages caused by the Allied blockade were increasingly leading to discontent and disorder.[7] Although morale on the German front line was reasonable, battlefield casualties, starvation rations and Spanish flu had caused a desperate shortage of manpower, and those recruits that were available were war-weary and disaffected.[8]

October 1918 telegrams and inter-Allied negotiations

On 29 September 1918, the German Supreme Army Command at Imperial Army Headquarters in Spa of occupied Belgium informed Emperor Wilhelm II and the Imperial Chancellor, Count Georg von Hertling, that the military situation facing Germany was hopeless. Quartermaster General Erich Ludendorff claimed that he could not guarantee that the front would hold for another two hours. Stating that the collapse of Bulgaria meant that troops destined for the Western Front would have to be diverted there, and this had "fundamentally changed the situation in view of the attacks being launched on the Western Front", Ludendorff demanded a request be given to the Entente for an immediate ceasefire.[9] In addition, he recommended the acceptance of the main demands of US president Woodrow Wilson (the Fourteen Points) including putting the Imperial Government on a democratic footing, hoping for more favorable peace terms. This enabled him to save the face of the Imperial German Army and put the responsibility for the capitulation and its consequences squarely into the hands of the democratic parties and the parliament. He expressed his view to officers of his staff on 1 October: "They now must lie on the bed that they've made for us."[10]

On 3 October 1918, the liberal Prince Maximilian of Baden was appointed Chancellor of Germany,[11] replacing Georg von Hertling in order to negotiate an armistice.[12] After long conversations with the Kaiser and evaluations of the political and military situations in the Reich, by 5 October 1918 the German government sent a message to Wilson to negotiate terms on the basis of a recent speech of his and the earlier declared "Fourteen Points". In the subsequent two exchanges, Wilson's allusions "failed to convey the idea that the Kaiser's abdication was an essential condition for peace. The leading statesmen of the Reich were not yet ready to contemplate such a monstrous possibility."[13] As a precondition for negotiations, Wilson demanded the retreat of Germany from all occupied territories, the cessation of submarine activities and the Kaiser's abdication, writing on 23 October: "If the Government of the United States must deal with the military masters and the monarchical autocrats of Germany now, or if it is likely to have to deal with them later in regard to the international obligations of the German Empire, it must demand not peace negotiations but surrender."[14]

In late October 1918, Ludendorff, in a sudden change of mind, declared the conditions of the Allies unacceptable. He now demanded the resumption of the war which he himself had declared lost only one month earlier. By this time however the German Army was suffering from poor morale and desertions were on the increase. The Imperial Government stayed on course and Ludendorff was dismissed from his post by the Kaiser and replaced by Lieutenant General Wilhelm Groener.

On 3 November 1918, Prince Max, who had been in a coma for 36 hours after an over-dose of sleep-inducing medication taken to help with influenza and only just recovered, discovered that both Turkey and Austria-Hungary had concluded armistices with the allies. General von Gallwitz had described this eventuality as being "decisive" to the Chancellor in discussions some weeks before, as it would mean that Austrian territory would become a spring-board for an Allied attack on Germany from the south. Revolution broke out across Germany the following day, together with a mutiny in the German High Seas Fleet. On 5 November, the Allies agreed to take up negotiations for a truce, now also demanding reparation payments.[15][16]

The latest note from Wilson was received in Berlin on 6 November 1918. That same day, the delegation led by Matthias Erzberger departed for France.[17] Aware that the refusal of the Kaiser to abdicate was a sticking-point in negotiations with the Allies as well as an impetus to revolution within Germany, Prince Max on his own authority announced that the Kaiser had abdicated and handed over power to Friedrich Ebert of the Social Democratic Party on 9 November. The same day, Philipp Scheidemann, also a Social Democrat, declared Germany a republic.[18]

Whilst the Germans sought negotiations along the lines of Wilson's 14 points, the French, British and Italian governments had no desire to accept them and President Wilson's subsequent unilateral promises. For example, they assumed that the de-militarization suggested by Wilson would be limited to the Central Powers. There were also contradictions with their post-War plans that did not include a consistent implementation of the ideal of national self-determination.[19] As Czernin points out:

The Allied statesmen were faced with a problem: so far they had considered the "fourteen commandments" as a piece of clever and effective American propaganda, designed primarily to undermine the fighting spirit of the Central Powers, and to bolster the morale of the lesser Allies. Now, suddenly, the whole peace structure was supposed to be built up on that set of "vague principles", most of which seemed to them thoroughly unrealistic, and some of which, if they were to be seriously applied, were simply unacceptable.[20]

To address this impasse Wilson suggested that the military chiefs be consulted. Douglas Haig, representing the British forces, urged moderation, stating that "Germany is not broken in the military sense" and that "it is necessary to grant Germany conditions that they can accept". and that surrender of occupied territories and Alsace-Lorraine would be "sufficient to seal the victory". The British also took the position that the German army should be kept mobilised as a counter to the spread of communist agitation. Ferdinand Foch, speaking for the French forces, agreed with Haig that the Germans "could undoubtedly take up a new position, and we could not prevent it", but, contrary to Haig, urged stringent terms including an occupation of the Rhineland with Allied bridgeheads over the Rhine, and the surrender of large quantities of military materiel. General Pershing, commander of the American forces, opposed any armistice being granted to the Germans. The combined effect of this feedback was to nullify Wilson's 14 points.[21]

German Revolution

The sailors' revolt that took place during the night of 29 to 30 October 1918 in the port of Wilhelmshaven spread across Germany within days and led to the proclamation of a republic on 9 November and to the announcement of the abdication of Wilhelm II.[a] Workers' and soldiers' councils took control in most major cities west of the Elbe, including Berlin, where the new Reich government, the socialist-dominated Council of the People's Deputies, had their full support.[22] One of the primary goals of the councils was an immediate end to the war.[23]

Also on 9 November, Max von Baden handed the office of chancellor to Friedrich Ebert, a Social Democrat who the same day became co-chair of the Council of the People's Deputies.[24] Two days later, on behalf of the new government, Matthias Erzberger of the Catholic Centre Party signed the armistice at Compiègne. The German High Command pushed the blame for the surrender away from the Army and onto others, including the socialists who were supporting and running the government in Berlin.[25] In the eyes of the German Right, the blame was carried over to the Weimar Republic when it was established in 1919. This resulted in a considerable amount of instability in the new republic.[26]

Negotiation process

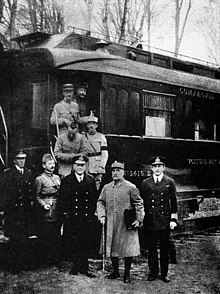

The Armistice was the result of a hurried and desperate process. The German delegation headed by Erzberger crossed the front line in five cars and was escorted for ten hours across the devastated war zone of Northern France, arriving on the morning of 8 November 1918. They were then taken to the secret destination aboard Foch's private train parked in a railway siding in the Forest of Compiègne.[27]

Foch appeared only twice in the three days of negotiations: on the first day, to ask the German delegation what they wanted, and on the last day, to see to the signatures. The Germans were handed the list of Allied demands and given 72 hours to agree. The German delegation discussed the Allied terms not with Foch, but with other French and Allied officers. The Armistice amounted to substantial German demilitarization (see list below), with few promises made by the Allies in return. The naval blockade of Germany was not completely lifted until complete peace terms could be agreed upon.[28][29]

There were very few negotiations. The Germans were able to correct a few impossible demands (for example, the decommissioning of more submarines than their fleet possessed), extend the schedule for the withdrawal and register their formal protest at the harshness of Allied terms. But they were in no position to refuse to sign. On Sunday, 10 November 1918, the Germans were shown newspapers from Paris to inform them that the Kaiser had abdicated. That same day, Ebert instructed Erzberger to sign. The cabinet had earlier received a message from Paul von Hindenburg, head of the German High Command, requesting that the armistice be signed even if the Allied conditions could not be improved on.[30][31]

The Armistice was agreed upon at 5:00 a.m. on 11 November 1918, to come into effect at 11:00 a.m. CET,[32][33] for which reason the occasion is sometimes referred to as "the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month". Signatures were made between 5:12 a.m. and 5:20 a.m., CET.[citation needed]

Allied Rhineland occupation

The occupation of the Rhineland took place following the Armistice. The occupying armies consisted of American, Belgian, British and French forces.

Prolongation

The Armistice was prolonged three times before peace was finally ratified. During this period it was also developed.

- First Armistice (11 November 1918 – 13 December 1918)

- First prolongation of the armistice (13 December 1918 – 16 January 1919)

- Second prolongation of the armistice (16 January 1919 – 16 February 1919)

- Trèves Agreement, 17 January 1919[34]

- Third prolongation of the armistice (16 February 1919 – 10 January 1920)[35]

- Brussels Agreement, 14 March 1919[36]

Peace was ratified at 4:15 p.m. on 10 January 1920.[37]

Key personnel

For the Allies, the personnel involved were all military. The two signatories were:[32]

- Marshal of France Ferdinand Foch, the Allied supreme commander

- First Sea Lord Admiral Rosslyn Wemyss, the British representative

Other members of the delegation included:

- General Maxime Weygand, Foch's chief of staff (later French commander-in-chief in 1940)

- Rear-Admiral George Hope, Deputy First Sea Lord

- Captain Jack Marriott, British naval officer, Naval Assistant to the First Sea Lord

For Germany, the four signatories were:[32]

- Matthias Erzberger, a civilian politician

- Count Alfred von Oberndorff, from the Foreign Ministry

- Major General Detlof von Winterfeldt, army

- Captain Ernst Vanselow, navy

In addition the German delegation was accompanied by two translators:[38]

- Captain Geyser

- Cavalry Captain (Rittmeister) von Helldorff

Terms

Among its 34 clauses, the armistice contained the following major points:[39]

A. Western Front

- Termination of hostilities on the Western Front, on land and in the air, within six hours of signature.[32]

- Immediate evacuation of France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Alsace–Lorraine within 15 days. Sick and wounded may be left for Allies to care for.[32]

- Immediate repatriation of all inhabitants of those four territories in German hands.[32]

- Surrender of matériel: 5,000 artillery pieces, 25,000 machine guns, 3,000 minenwerfer, 1,700 aircraft (including all night bombers), 5,000 railway locomotives, 150,000 railway carriages and 5,000 road trucks.[32]

- Evacuation of territory on the west side of the Rhine plus 30 km (19 mi) radius bridgeheads of the east side of the Rhine at the cities of Mainz, Koblenz, and Cologne within 31 days.[32]

- Vacated territory to be occupied by Allied troops, maintained at Germany's expense.[32]

- No removal or destruction of civilian goods or inhabitants in evacuated territories and all military matériel and premises to be left intact.[32]

- All minefields on land and sea to be identified.[32]

- All means of communication (roads, railways, canals, bridges, telegraphs, telephones) to be left intact, as well as everything needed for agriculture and industry.[32]

B. Eastern and African Fronts

- Immediate withdrawal of all German troops in Romania and in what were the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Russian Empire back to German territory as it was on 1 August 1914, although tacit support was given to the pro-German West Russian Volunteer Army under the guise of combating the Bolsheviks. The Allies to have access to these countries.[32]

- Renunciation of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk with Russia and of the Treaty of Bucharest with Romania.[32]

- Evacuation of German forces in Africa.[32]

C. At sea

- Immediate cessation of all hostilities at sea and surrender intact of all German submarines within 14 days.[32]

- Listed German surface vessels to be interned within 7 days and the rest disarmed.[32]

- Free access to German waters for Allied ships and for those of the Netherlands, Norway, Denmark and Sweden.[32]

- The naval blockade of Germany to continue.[32]

- Immediate evacuation of all Black Sea ports and handover of all captured Russian vessels.[32]

D. General

- Immediate release of all Allied prisoners of war and interned civilians, without reciprocity.[40]

- Pending a financial settlement, surrender of assets looted from Belgium, Romania and Russia.[32]

Aftermath

The British public was notified of the armistice by a subjoined official communiqué issued from the Press Bureau at 10:20 a.m., when British Prime Minister David Lloyd George announced: "The armistice was signed at five o'clock this morning, and hostilities are to cease on all fronts at 11 a.m. to-day."[41] An official communique was published by the United States at 2:30 pm: "In accordance with the terms of the Armistice, hostilities on the fronts of the American armies were suspended at eleven o'clock this morning."[42]

News of the armistice being signed was officially announced towards 9:00 a.m. in Paris. One hour later, Foch, accompanied by a British admiral, presented himself at the Ministry of War, where he was immediately received by Georges Clemenceau, the Prime Minister of France. At 10:50 a.m., Foch issued this general order: "Hostilities will cease on the whole front as from November 11 at 11 o'clock [Central European Time]. The Allied troops will not, until further order, go beyond the line reached on that date and at that hour."[43] Five minutes later, Clemenceau, Foch and the British admiral went to the Élysée Palace. At the first shot fired from the Eiffel Tower, the Ministry of War and the Élysée Palace displayed flags, while bells around Paris rang. Five hundred students gathered in front of the Ministry and called upon Clemenceau, who appeared on the balcony. Clemenceau exclaimed "Vive la France!" – the crowd echoed him. At 11:00 a.m., the first peace-gunshot was fired from Fort Mont-Valérien, which told the population of Paris that the armistice was concluded, but the population were already aware of it from official circles and newspapers.[44]

Although the information about the imminent ceasefire had spread among the forces at the front in the hours before, fighting in many sections of the front continued right until the appointed hour. At 11 a.m., there was some spontaneous fraternization between the two sides but in general, reactions were muted. A British corporal reported: "...the Germans came from their trenches, bowed to us and then went away. That was it. There was nothing with which we could celebrate, except cookies."[45] On the Allied side, euphoria and exultation were rare. There was some cheering and applause, but the dominant feeling was silence and emptiness after 52 exhausting months of war.[45] According to Thomas R. Gowenlock, an intelligence officer with the U.S. First Division, shelling from both sides continued during the rest of the day, ending only at nightfall.[46][47]

The peace between the Allies and Germany was subsequently settled in 1919, by the Paris Peace Conference and the Treaty of Versailles that same year.[citation needed]

Last casualties

Many artillery units continued to fire on German targets to avoid having to haul away their spare ammunition. The Allies also wished to ensure that, should fighting restart, they would be in the most favourable position. Consequently, there were 10,944 casualties, of whom 2,738 men died, on the last day of the war.[2]

An example of the determination of the Allies to maintain pressure until the last minute, but also to adhere strictly to the Armistice terms, was Battery 4 of the US Navy's long-range 14-inch railway guns firing its last shot at 10:57:30 a.m. from the Verdun area, timed to land far behind the German front line just before the scheduled Armistice.[48]

Augustin Trébuchon was the last Frenchman to die when he was shot on his way to tell fellow soldiers, who were attempting an assault across the Meuse river, that hot soup would be served after the ceasefire. He was killed at 10:45 a.m.[citation needed]

Marcel Toussaint Terfve was the last Belgian soldier to die as he was mortally wounded from German machine gun fire and died from his lung wound at 10:45 a.m.[citation needed]

Earlier, the last British soldier to die, George Edwin Ellison of the 5th Royal Irish Lancers, was killed that morning at around 9:30 a.m. while scouting on the outskirts of Mons, Belgium.[citation needed]

The final Canadian, and Commonwealth, soldier to die, Private George Lawrence Price, was shot and killed by a sniper while part of a force advancing into the Belgian town of Ville-sur-Haine just two minutes before the armistice to the north of Mons at 10:58 a.m.[citation needed]

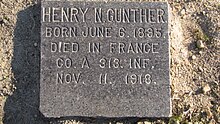

Henry Gunther, an American, is generally recognized as the last soldier killed in action in World War I. He was killed 60 seconds before the armistice came into force while charging astonished German troops who were aware the Armistice was nearly upon them. He had been despondent over his recent reduction in rank and was apparently trying to redeem his reputation.[49][50]

The last German to die in the war, though his name is not fully known, is believed to be a Lieutenant by the name of Tomas. At a time shortly after 11:00 a.m, perhaps 11:01 a.m, he exited his trench and began to walk across no-mans-land to inform the Americans there that the Armistice had just gone into effect, and that his soldiers would soon be evacuating their trenches. The Americans, who had not yet heard news of the armistice, opened fire, killing him instantly.

News of the armistice only reached Germany's African forces, still fighting in Northern Rhodesia (today's Zambia), about two weeks later. The German and British commanders then had to agree on the protocols for their own armistice ceremony.[51]

After the war, there was a deep shame that so many soldiers died on the final day of the war, especially in the hours after the treaty had been signed but had not yet taken effect. In the United States, Congress opened an investigation to find out why and if blame should be placed on the leaders of the American Expeditionary Forces, including John Pershing.[52] In France, many graves of French soldiers who died on 11 November were backdated to 10 November.[49]

Legacy

The celebration of the Armistice became the centrepiece of memories of the war, along with salutes to the unknown soldier. Nations built monuments to the dead and the heroic soldiers, but seldom aggrandizing the generals and admirals.[54] 11 November is commemorated annually in many countries under various names such as Armistice Day, Remembrance Day, Veterans Day, and in Poland, it is Independence Day.[citation needed]

During World War II, after German success in the Battle of France, Adolf Hitler arranged that negotiations for an end of hostilities with France would take place at Compiègne in the same rail car as the 1918 conference. The Armistice of 22 June 1940 was portrayed as revenge for Germany's earlier defeat, and the Glade of the Armistice was mostly destroyed.[citation needed]

The end of the Second World War in China (end of the Second Sino-Japanese War) formally took place on 9 September 1945 at 9:00 a.m. (the ninth hour of the ninth day of the ninth month). The date was chosen to echo the 1918 Armistice (on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month), and because "nine" is a homophone of the word for "long lasting" in Chinese (to suggest that the peace won would last forever).[55]

Stab-in-the-back myth

In November 1918, the Allies had ample supplies of manpower and materiel to invade Germany. Additionally, with the fall of Austria-Hungary, an offensive was being prepared across the Alps towards Munich, Poland was in turmoil, and an air-offensive was being planned by the Independent Air Force under Trenchard against Berlin.[6] Yet at the time of the armistice, the Western Front was still some 720 kilometres (450 mi) from Berlin, and the Kaiser's armies had retreated from the battlefield in good order.[citation needed] These factors enabled Hindenburg and other senior German leaders to spread the story that their armies had not really been defeated. This resulted in the stab-in-the-back myth, which attributed Germany's defeat not to its inability to continue fighting (even though up to a million soldiers were suffering from the 1918 flu pandemic and unfit to fight), but to the public's failure to respond to its "patriotic calling" and the supposed sabotage of the war effort, particularly by Jews, Socialists, and Bolsheviks.[56][57] The myth that the German Army was "stabbed in the back" by the Social Democratic government was further pushed by reviews in the German press that grossly misrepresented British Major General Frederick Maurice's book, The Last Four Months. "Ludendorff made use of the reviews to convince Hindenburg."[58]

In a hearing before the Committee on Inquiry of the National Assembly on November 18, 1919, a year after the war's end, Hindenburg declared, "As an English general has very truly said, the German Army was 'stabbed in the back'."[58]

See also

Notes

- ^ The announcement by Prince Maximilian of Baden had great effect, but the abdication document was not formally signed until 28 November 1918.

References

Citations

- ^ "Armistice: The End of World War I,1918". EyeWitness to History. 2004. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ a b Persico 2005.

- ^ Lloyd 2014, p. 97

- ^ Mallinson 2016, p. 304

- ^ Mallinson 2016, pp. 308–309

- ^ a b Liddell Hart, B.H. (1930). The Real War. Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-0-316-52505-3. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Mallinson 2016, p. 306

- ^ Lloyd 2014, pp. 9–10

- ^ Liddell Hart, B.H. (1930). The Real War. Little, Brown, and Company. p. 378. ISBN 978-0-316-52505-3. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Axelrod 2018, p. 260.

- ^ Head of Government. Germany was - and remains to this day - a federal state. Individual states had their own kings and prime ministers. The Kaiser was also King of Prussia, the largest state, and the Imperial Chancellor almost always prime minister of Prussia.

- ^ Czernin 1964.

- ^ Czernin 1964, p. 7.

- ^ Czernin 1964, p. 9.

- ^ Morrow 2005, p. 278.

- ^ Liddell Hart, B.H. (1930). The Real War. Little, Brown, and Company. p. 382. ISBN 978-0-316-52505-3. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Leonhard 2014, p. 916.

- ^ "Arnold Brecht on his First Weeks in the Chancellery (Retrospective Account, 1966)" (PDF). GHDI - German History in Documents and Images. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Leonhard 2014, p. 884.

- ^ Czernin 1964, p. 23.

- ^ Liddell Hart, B.H. (1930). The Real War. Little, Brown, and Company. pp. 383–384. ISBN 978-0-316-52505-3. Retrieved 28 February 2024.

- ^ Sturm, Reinhard (23 December 2011). "Vom Kaiserreich zur Republik 1918/19" [From Empire to Republic 1918/19]. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (in German). Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Piper, Ernst (2018). "Deutsche Revolution 1918/19". Informationen zur Politischen Bildung (in German) (33): 14.

- ^ Mommsen, Hans (1996). The Rise and Fall of Weimar Democracy. Translated by Forster, Elborg; Jones, Larry Eugene. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 21, 28–29. ISBN 978-0807847213.

- ^ Scriba, Arnulf (1 December 2014). "Die Dolchstosslegende" [The Stab-in-the-back Myth]. Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ Barth, Boris (8 October 2014). Daniel, Ute; Gatrell, Peter; Janz, Oliver; Jones, Heather; Keene, Jennifer; Kramer, Alan; Nasson, Bill (eds.). "Stab-in-the-back Myth". 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Freie Universität Berlin. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Rudin 1967, pp. 320–349.

- ^ Rudin 1967, p. 377.

- ^ Haffner 2002, p. 74.

- ^ Haffner 2002, p. 113.

- ^ Rudin 1967, p. 389.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Armistice 1918.

- ^ Poulle 1999.

- ^ Salter 1921, pp. 223, 228–229.

- ^ Edmonds & Bayliss 1987, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Salter 1921, pp. 223, 229.

- ^ Edmonds & Bayliss 1987, p. 189.

- ^ "The Armistice delegations in 1918".

- ^ Rudin 1967, pp. 426–427.

- ^ Leonhard 2014, p. 917.

- ^ "Peace Day in London". The Poverty Bay Herald. Gisborne, New Zealand. 2 January 1919. p. 2. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "World Wars: Daily Mirror Headlines: Armistice, Published 12 November 1918". London: BBC. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Reich Quit Last War Deep in French Forest". The Milwaukee Journal. Milwaukee. 7 May 1945. p. 10. Retrieved 7 September 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "The News in Paris". The Daily Telegraph. 11 November 1918.

- ^ a b Leonhard 2014, p. 919.

- ^ "How World War I Soldiers Celebrated the Armistice". 10 November 2016.

- ^ Gowenlock, Thomas (1937). Soldiers of Darkness. Doubleday, Doran & Co. OCLC 1827765.

- ^ Breck 1922, p. 14.

- ^ a b "The last soldiers to die in World War I". BBC News Magazine. 29 October 2008. Archived from the original on 7 November 2008. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ "Michael Palin: My guilt over my great-uncle who died in the First World War". The Daily Telegraph. 1 November 2008. Archived from the original on 4 November 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

We unearthed many heart-breaking stories, such as that of Augustin Trébuchon, the last Frenchman to die in the War. He was shot just before 11 a.m. on his way to tell his fellow soldiers that hot soup would be available after the ceasefire. The parents of the American Pte Henry Gunther had to live with news that their son had died just 60 seconds before it was all over. The last British soldier to die was Pte George Edwin Ellison.

- ^ "Where World War One finally ended". BBC News. 25 November 2018. Archived from the original on 26 November 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Persico 2005, p. IX.

- ^ "Armistice Day: moving events mark 100 years since end of first world war – as it happened". The Guardian. 11 November 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ Theodosiou 2010, pp. 185–198.

- ^ Hans Van De Ven, "A call to not lead humanity into another war", China Daily, 31 August 2015.

- ^ Baker 2006.

- ^ Chickering 2004, pp. 185–188.

- ^ a b Shirer 1960, p. 31.

Sources

- . 11 November 1918 – via Wikisource.

- Axelrod, Alan (2018). How America Won World War I. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Baker, Kevin (June 2006). "Stabbed in the Back! The past and future of a right-wing myth". Harper's Magazine.

- Breck, Edward (1922). The United States naval railway batteries in France. Department of the Navy, Office of Naval Records and Library. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- Chickering, Rodger (2004). Imperial Germany and the Great War, 1914–1918. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83908-2. OCLC 55523473.

- Czernin, Ferdinand (1964). Versailles, 1919. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Haffner, Sebastian (2002). Die deutsche Revolution 1918/19 [The German Revolution 1918/19] (in German). Kindler. ISBN 978-3-463-40423-3.

- Edmonds, James Edward; Bayliss, Gwyn M. (1987) [1944]. Bayliss, Gwyn M (ed.). The Occupation of the Rhineland 1918–29. History of the Great War. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-290454-0. OCLC 59076445.

- Leonhard, Jörn (2014). Die Büchse der Pandora: Geschichte des Ersten Weltkriegs [Pandora's Box : History of the First World War] (in German). Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-66191-4.

- Lloyd, Nick (2014). Hundred Days: The End of the Great War. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0241953815.

- Mallinson, Allan (2016). Too Important for the Generals: Losing and Winning the First World War. London: Bantam Press. ISBN 978-0593058183.

- Morrow, John H. Jr. (2005). The Great War: An Imperial History. Psychology Press.

- Persico, Joseph E. (2005). 11th Month, 11th Day, 11th Hour (illustrated, reprint ed.). London: Random House. ISBN 978-0-09-944539-5. OCLC 224671506.

- Poulle, Yvonne (1999). "La France à l'heure allemande" (PDF). Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes (in French). 157 (2): 493–502. doi:10.3406/bec.1999.450989. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 September 2015.

- Rudin, Harry Rudolph (1967). Armistice, 1918. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780208002808.

- Salter, Arthur (1921). Allied Shipping Control: An Experiment in International Administration. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Shirer, William Lawrence (1960). The rise and fall of the Third Reich: a history of Nazi Germany. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781451642599.

- Theodosiou, Christina (2010). "Symbolic narratives and the legacy of the Great War: the celebration of Armistice Day in France in the 1920s". First World War Studies. 1 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1080/19475020.2010.517439. ISSN 1947-5020. S2CID 153562309.

Further reading

- Best, Nicholas (2009). The Greatest Day in History: How, on the Eleventh Hour of the Eleventh Day of the Eleventh Month, the First World War Finally Came to an End. New York City: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-772-0. OCLC 191926322.

- Brook-Shepherd, Gordon (1981). November 1918: the last act of the Great War. Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-216558-7. OCLC 8387384.

- Cuthbertson, Guy (2018). Peace at Last: A Portrait of Armistice Day, 11 November 1918. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300254877.

- Halperin, S. William (March 1971). "Anatomy of an Armistice". The Journal of Modern History. 43 (1): 107–112. doi:10.1086/240590. ISSN 0022-2801. OCLC 263589299. S2CID 144948783.

- Kennedy, Kate, and Trudi Tate, eds. The Silent Morning: Culture and Memory After the Armistice (2013); 14 essays by scholars regarding literature, music, art history and military history table of contents Archived 1 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Lowry, Bullitt, Armistice, 1918 (Kent State University Press, 1996) 245pp

- Triplet, William S. (2000). Ferrell, Robert H. (ed.). A Youth in the Meuse-Argonne. Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press. pp. 284-85. ISBN 0-8262-1290-5. LCCN 00029921. OCLC 43707198.

- Weintraub, Stanley. A stillness heard round the world: the end of the Great War (1987)

External links

- Armistice records and images from the UK Parliament Collections

- La convention d'armistice du 11 novembre 1918 The Armistice agreement (in French – link updated, accessed 13 February 2014)

- The Armistice Demands, translated into English from German Government statement The World War I Document Archive, Brigham Young University Library, accessed 27 July 2006

- Waffenstillstandsbedingungen der Alliierten Compiègne, 11. November 1918 (German text of the Armistice, abbreviated)

- Watch six online National Film Board of Canada documentaries about the Armistice

- Map of Europe on Armistice Day at omniatlas.com

- European newspapers from 12 November 1918 – The European Library via Europeana

- The Moment the Guns Fell Silent – American Front, Moselle River 11 November 1918 – Metro.co.uk

- Sound of the Armistice – Recreated sounds at the moment of the armistice – by Coda to Coda Labs