Armenian dress

The Armenian Taraz (Armenian: տարազ, taraz;[a]), also known as Armenian traditional clothing, reflects a rich cultural tradition. Wool and fur were used by the Armenians along with the cotton that was grown in the fertile valleys. During the Urartian period, silk imported from China was used by royalty. Later, the Armenians cultivated silkworms and produced their own silk.[1][2]

The collection of Armenian women's costumes begins during the Urartu time period, wherein dresses were designed with creamy white silk, embroidered with gold thread. The costume was a replica of a medallion unearthed by archaeologists at Toprak Kale near Lake Van, which some 3,000 years ago was the site of the capital of the Kingdom of Urartu.[3]

Overview

The Armenian national costume, having existed through long periods of historical development, was one of the signals of self-preservation for the Armenian culture. Being in an area at the crossroads of diverse eastern styles, Armenian dress is significant in not only borrowing but also often playing an influential role on neighboring nations.[4]

The costume can be divided into two main regions: Western Armenians and Eastern Armenians. Which in turn are divided into separate subregions.

The costume of the Armenians of Western Armenia is mainly divided into two regions:

1. Areas of the Eastern Provinces: Taron (including Sasun), Bardzr Hayk, Vaspurakan, and Baghesh.

2. The regions of Sebastia, Kayseri, Cilicia in the western states, and Kharberd-Tigranakert in the south.

The first group kept closer to the traditions of the Armenian costume while in the second group, the influence of some Anatolian cultures are seen.

Eastern Armenian costume can be divided into three regions:

1. Syunik-Artsakh, Zangezur, and Ayrarat.

3. Gandzak, Gugark, Shirak, Javakhk.

Colors

The Armenian costume is dominated by the colors of the four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. According to the 14th-century Armenian philosopher Grigor Tatatsi, the Armenian costume is made to express the ancestral soil, the whiteness of the water, the red of the air, and the yellow of the fire. Apricot symbolizes prudence and common sense, red symbolizes courage and martyrdom, blue symbolizes heavenly justice, white symbolizes purity. Some of the techniques used in making these costumes have survived to this day and are actively used in the applied arts, however, there are techniques that have been lost. Each province of Armenia stands out with its costume. The famous centers of Armenian embroidery – Van-Vaspurakan, Karin, Shirak, Syunik-Artsakh, Cilicia – stand out with their rhythmic and stylistic description of ornaments, color combinations and composition.[1]

Timeline

Ancient period: 900–600 BCE

The Urartians who were the predecessors to the Armenians wore a dress similar to that of Assyrians which consisted of short-sleeved tunics worn bare or with a shawl surrounding it. The Urartians decorated themselves with metal ornaments such as necklaces, bracelets, earrings, and pins. These metal ornaments were engraved with lion heads while necklaces of stone beads and long metal pins were draped across the body. Metal belts were an important part of the Urartian costume as well. The making of metal belts was considered an art form with magical scenes and animals being engraved into the belt to protect the wearer.[5]

Classical period: 600 BCE – 600 CE

The traditional dress of Armenians underwent a significant shift following the emergence of the Kingdom of Armenia as a distinct political entity. Armenian men wore fitted trousers and a distinct hat known as the Phrygian cap. This later evolved into the balshik which is a flexible accessory that is worn by shepherds and religious leaders alike.[5]

Medieval period: 600–1600 CE

Based on the works of Armenian manuscripts as well as images found on churches, coins, and khachkars, we can see that the Armenian elite wore clothing similar to that of Byzantine and Arab royalty, such as Turbans. Armenians held onto their unique traditions while also adopting from neighboring societies such as head coverings becoming commonplace for Armenian women.[5]

19th century

In her 1836 novel titled The City of The Sultan; and Domestic Manners of the Turks, Julia Pardoe described the Armenian merchants she observed immediately upon disembarking in the port of Stamboul:[6]

As I looked on the fine countenances, the noble figures, and the animated expression of the party, how did I deprecate their shaven heads, and the use of the frightful calpac, which I cannot more appropriately describe than by comparing it to the iron pots used in English kitchens, inverted! The graceful pelisse, however, almost makes amends for the monstrous head-gear, as its costly garniture of sable or marten-skin falls back, and reveals the robe of rich silk, and the cachemire shawl folded about the waist.

Pardoe also mentions they wore bejeweled rings and carried in their hands "pipes of almost countless cost.”

Nowadays

Armenian traditional clothing started to fall out of use in the 1920s and was almost completely replaced by modern clothing by the 1960s. Today, Armenian traditional clothing is mostly used for dance performances where girls put on an arkhalig and long dress to simulate taraz while boys wear dark colored loose pants and a fitted jacket. In some areas of Armenia and Karabakh, elderly women still wear a short headscarf. Photo studios in Armenia allow for new generations to take pictures in traditional clothing and some women in recent times have begun to wear taraz again.[5]

An annual festival celebrating Armenian traditional dress known as Taraz Fest is hosted every year in Yerevan and Stepanakert by the Teryan cultural center and consists of showcases of the cultural dress.[7]

Men's clothing

Eastern Armenia

The basis of the Armenian men's body clothing was the lower shirt and pants. They were sewn from homemade canvas at home. The most common was the traditional tunic-shaped men's shirt – Shapik (Armenian: շապիկ) made of two cloths.[5] In an Armenian family, men's clothes, especially the head of the house, were paid special attention, as men judged the family as a whole by their appearance.[2]

The overall fashion of the Eastern Armenian costume was Caucasian, close to similar clothing worn by neighboring peoples in the Caucasus such as Azerbaijanis, Georgians, Dagestanis, and Chechens, among others.

Belt clothes

Men's body pants – Vartik (Armenian: վարտիկ; also votashor, tuban or pohan) differed from women's in that they did not have an applied decorative border at the bottom of the ankle; their pants were tucked into knitted socks and windings. A cap and vartic of traditional cut were worn in Armenia by men of all ages, from young boys to the elderly.[8]

Ballovars – shalvar (Armenian: շալվար) were worn over the body pants. They were sewn from homemade rough-shaft fabric painted black, less often dark blue or brown in the same fabric as the vartic.[1][5]

Outerwear

The basis of outer shoulder clothing in Eastern Armenia was Arkhalugh and Chukha. Arkhalugh-type clothing has a centuries-old tradition among Armenians, as evidenced by images on tombstones and medieval miniatures. It was widespread and worn by the entire male population, starting from boys aged 10–12. Arkhalugh was sewn from purchased fabrics (satin, eraser, chintz, shawl), black, blue, brown tones, lined. Its decoration was a galun ribbon in the tone of the main material, which was covered with a collar, chest incision, hem and sleeves. In wealthy families, such as in the merchant class of Yerevan, along with the ribbon, a silk cord was added.[1]

Arkhalugh (Armenian: արխալուղ) – a long, tight, waist-jacket made of fabrics including silk, satin, cloth, cashmere and velvet, depending on the social status of its owner. It was usually girded with a silver belt, less often with a belt or a leather belt with false silver buttons.[2]

With a number of similarities to the Arkhalugh, the Chukha (Armenian: չուխա) had a wider functional purpose. The Chukha is a male humeral outerwear with layers and gathers that was detachable at the waist. It was made of cloth, tirma, and homespun textiles. Outerwear served not only as warm clothes, but as clothing for special occasions.[8] Most chukhas were decorated with a bandolier for gazyr cartridges on both sides of the coat, although Armenians would seldom wear the chukha with the cartridges inserted. The right to wear a chukha symbolized a certain socio-age status, as a rule, it was worn from the age of majority (from 15 to 20 years). The Chukhas were dressed in a mushtak or burka, and later as an urban influence. Sheepskin fur coat or mushtak as clothes were worn by the wealthy, mainly of the older generation.[2]

Some Eastern Armenian men additionally chose to wear a dagger, known as a Khanchal (Armenian: Խանչալ) or Dashuyn (Armenian: Դաշույն) over either the Chukha or the Arkhalugh. It was suspended from either a leather or silver belt and hung diagonally across the man's waist.[9] Such daggers were widespread throughout the Caucasus region, including Armenia. However, due to the lack of the strong warrior culture that was present in the areas north of Armenia, the dagger was a far less ubiquitous part of a man's outfit in Armenia than it was elsewhere in the region.

Burka (Armenian: այծենակաճ, aitsenakach) was the only cape in traditional Armenian costume. Armenians wore two types of burqa: fur and felt. Fur burka was made of goat wool, with fur outside, using long-pile fur. Felt burka and in some areas fur (Lori) was worn by shepherds.[5] This was often complete with a Bashlyk, a type of hood which was suspended from the back of the Burka and worn over the Papakh to protect against rain.

The men's clothing complex also included a leather belt, which was worn over the arkhalugh. The leather belt had a silver buckle and false ornaments engraved with plant ornaments.[5]

Men's wedding clothes, which were both festive and culturally significant, were distinguished by the fact that the arkhalugh was made of more expensive fabric, the chukha and shoelaces were red (this color was considered to be a guardian), and the belt was silver, which they received during the wedding from the bride's parents. This type of clothing of Karabakh men was also common among other Eastern Armenians, in particular in Syunik, Gogthan, as well as in Lori.[10]

Headgear

The standard headgear of Eastern Armenians was a fur hat – Papakh (Armenian: փափախ), sewn from sheep's skins.[11] Papakhs came in a variety of different shapes and sizes, with men of different regions and villages having different preferences. Generally speaking, men from Southern Armenia and Karabakh preferred a taller and more cylindrical style of papakh, while men from Northern Armenia usually wore one that was low and wide. The most expensive and prestigious was considered to be made from Bukhara sheep wool, which was worn by representatives of the wealthy classes, especially in cities. In these cities, very high, close to cylindrical, hats were worn complete with a chuhka with folding sleeves. The headgear and hat, in particular, were the embodiment of the honor and dignity of an Armenian man. Throwing his papakha on the ground was equated to his shame and dishonor. According to traditional etiquette, in certain situations, the man was supposed to take off his hat at the entrance to church, during funerals, when meeting highly revered and respected people, etc.[1]

Western Armenia

Traditional Armenian clothing from Western Armenia was generally standard throughout despite regional differences and had a similar silhouette, bright color scheme that was distinguished by colorfulness, and an abundance of embroidery.[1]

Men's bodywear had a similar cut to the East Armenian wear. However, the body shirt was distinguished by a side section of the gate. The body pants – vartik, were covered without a step wedge, but with a wide insert strip of fabric, as a result of which the width of such pants was often almost equal to their length. They were made of woolen multicolored threads.[1]

The traditional clothing of some Western Armenian provinces, namely those around lake Van, was a regional form of dress rather than an ethnic one, as many neighboring peoples such as Kurds also dressed in a similar fashion. However, as Armenians had a virtual monopoly on weaving and dress-making in the region, coupled with the fact that Armenians were the oldest living inhabitants of the area, it is likely that it was adopted from Armenians by the neighboring peoples.[12]

Outerwear

The gate and long sleeves of the upper shirt, Ishlik, were sewn with geometric patterns of red threads. In a number of regions such as in (Vaspurakan and Turuberan), the sleeve of the shirt ended with a long hanging piece – jalahiki. The shirt was worn with a kind of vest, a spruce (tree) with open breasts, from under which the shirt's embroidered breasts were clearly visible. Such a vest was a characteristic component of the traditional men's suit only in Western Armenia.[13]

From above, a short, waist-to-waisted woolen jacket was worn on the top – a batchkon, a one-piece-sleeved salt, often quilted. The wealthy Armenians chose the thinnest, especially Shatakh cloth, mostly of domestic and local handicrafts, and tried to sew all parts of the suit from one fabric".[11]

On top of the top were worn short (up to the waist) swing clothes with short sleeves – Kazakhik made of goat fur or felt aba. The goat's jacket, covered with braids at the edges and with bundles of fur on its shoulders, was worn mainly by wealthy villagers.[14]

The outer warm clothes also included a long straight "Juppa". In wealthier families, the juppa was quilted and lined. It was preferred to be worn by mature men. In winter, in some, mainly mountainous regions (Sasun), wide fur coats made of sheepskin were worn, without a belt.

The belt as an indispensable part of men's suit in most regions Western Armenia was distinguished by its originality. The colored patterned belt was "rather a bandage around the waist. A long, wide shawl, knitted or woven, folded in width in several layers, was wrapped twice or more around the waist. The deep folds of the belt served as a kind of pocket for a handkerchief, kisset, wallet. For such a belt, you could plug both a long tube and a knife with a handle, and if necessary a dagger".[11]

The silver belt was an accessory of the city costume, it was worn in Karin, Kars, Van and other centers of highly developed craftsmanship production. Citizens, artisans, and wealthy peasants alike had belts made of massive silver plaques.[1]

Headgear

The headgear in Western Armenia consisted of hats of various shapes (spherical, conical), felt, wool knitted and woven, which were usually worn in addition to the handkerchief. They had regional differences in the materials used to manufacture it as well as the style and color scheme of the ornament. A felt white cone-shaped hat was widespread – koloz with a pointed or rounded top.[15]

The widespread arakhchi, also known as arakhchin (Armenian: արախչի), was a truncated skull cap, knitted from wool or embroidered in single youth with multicolored woolen thread, with a predominance of red.[16] The way this traditional headdress was worn was a marker of its owner's marital condition, just as in Eastern Armenia, the right to wear an arakhicki belonged to a married man.[15]

Hamshen

The Hamshen province of Armenia had its own unique costume, sharing many similarities with the Caucasian costume found in Eastern Armenia. It was generally close to similar clothing worn by the neighboring Laz, Adjarian and Pontic Greek peoples. By the end of the 19th century, this costume included an undershirt, a top cover shirt, an Arkhalukh, and a short Chukha which reached a little below the waist. Hamshen Armenians traditionally wore very wide and long pants, however by the end of the 19th century this was replaced by a thinner pair of trousers called zipkas, worn with a pair of high boots. A wool or silk belt, 4–5 meters long, was tied over the trousers.

In winter, many villagers wore a Kepenek, a felt outercoat similar to the Burka, except with a hood to cover the head. As everyday headwear, men wore a Bashlyk made of silk or wool which was tied around the head to form a headband. Men who owned arms completed their outfit with a series of firearms accessories, a knife, and a Khanchal dagger.[17]

Women's clothing

Eastern Armenia

At the beginning of the 20th century, women's clothing, unlike men's clothing, still preserved its traditional complexes in historical and ethnographic regions. Women's clothing of eastern and western Armenians was more homogeneous than men's clothing. The main difference was the abundance of embroidery and jewelry in a women's suit from Western Armenia as opposed to Eastern Armenia.

Clothes

In Armenia, women wore a long red shirt – halav made of cotton fabric with oblique wedges on the sides, long straight sleeves with a gusset and a straight incision of the gate. This shirt was worn mainly by girls and young women. Long body pants were sewn from the same red fabric as the shirt, on a white lining and waist held on hold with the help of honjang.[15]

Holiday pants were sewn in silk red fabric on a white fabric lining. The lower ends of the pants collected from the ankles were to be visible from under the outerwear, so this part was sewn from more expensive and beautiful fabric and sewn (in Yerevan and Ararat) with gold embroidery or decorated (Syunik, Artsakh) with a strip of black velvet with gold-plated braid. In the women's complex of the provinces Syunik and Artsakh, an important part was the upper shirt – virvi khalav (Armenian: վիրվի հալավ) made of red silk or calico with round gate and chest incision with black velvet or satin, as well as sewn silver small jewelry.[15]

Outerwear

In the early 20th century, women's outerwear differed in great variety among Armenians. Its basis in Eastern Armenia was a long swing dress – arkhalugh with one-piece front shelves and a trimmed back, an elegant long neckline on the chest, fastened only at the waist. They sewed arkhalughs from sitz, satin or silk, usually blue, green or purple colors, lined in thin cotton vatina, lined with longitudinal lines and vertical lines on the sleeves. It was necessary to have two dresses: everyday dresses made of cotton and festive dresses made of expensive silk fabric.[18]

The clothes for the exit were a dress – mintana (Armenian: մինթանա), worn on solemn occasions on top of the arkhalig of the same cut, but without side seams.[1]

An integral part of traditional women's clothing was the belt. In the Ararat Valley, especially in the urban environment of Yerevan, the complex of women's clothing included a fabric silk belt with two long curtain rods embroidered with silk and gold threads. Syunik and Artsakh also used a leather belt with a large silver buckle and sewn silver plates made in the technique of engraving, filigree and black.[19]

Headgear

The most characteristic and complex part of Eastern Armenian taraz was a women's headdress. Before a woman was married, the hair was freely released back with several pigtails and tied to the head with a handkerchief. After marriage, the Armenian woman was to "tie her head", i.e. they put on a special "towagon" on her head – palti (Nagorno-Karabakh, Syunik), pali, poli (Meghri, Agulis), baspind (Yerevan, Ashtarak). Underneath it, a ribbon with coins (silver, very rich – with gold) or with special hangers was tied on the forehead, and silver balls hung on both sides of the face through the whiskey or interspersed with coral. The nose and mouth were tightly tied first with a white and then with a colored (red, green) handkerchief.[20]

Due to Islamic influences, many Armenian women wore a Chador when going outside per the rules of the dominant Persian or Turkish cultural norms.[5]

Western Armenia

The western Armenian variety of women's clothing was distinguished by a bright color scheme and rich decorative design. The bodywork in cut was similar to that of Eastern Armenia, with the only difference being that the shirts were sewn from white cotton fabric.

Outerwear

Western Armenian women wore a swinging one-piece dress – ant'ari. On top of the "antari" on solemn occasions, as well as in the cold season, a dress – juppa, was worn. This dress could be festive (burgundy, purple, blue velvet or silk, colored woolen fabric in stripes) and everyday (made of dark blue cloth).[21]

A distinctive feature of traditional women's clothing in Western Armenia was the apron – mezar. Made of cotton or expensive (velvet, cloth) fabrics, abundantly decorated (especially wedding), it was a necessary part of the outfit: as in the east it was "shameful" to go out with an open chin, so here it was "shameful" to appear without an apron.[22] The classic version of it is a red cloth apron in a set of Karin-Shirak's clothes with exquisite sewing and braid, which was tied to the "antari".

With such an apron, the open chest of the dress was covered with an embroidered bib – "krckal" rectangular or trapezoidal shape made of silk, velvet or woolen fabric, in girls and young women decorated with rich embroidery along the gate and on the chest, and "'juppa" was replaced by a jacket – "salta"" or "kurtik".[11] This swing short (to the waist) jacket was made of purple, blue, burgundy velvet or green, blue silk fabric. The jacket was festive clothes and struck by the beauty of patterned embroidery. Warm outerwear, in particular in Vaspurakan, was dalma, a kind of long coat made of black cloth lined. This swinging, waist-fitting and braided with braided gold and silk threads, the cut was similar to a "juppa". It was mainly worn by girls and young women.[23]

Headgear

The women's headgear stood out for its special wealth and beauty. The girls braided their hair in numerous braids (up to 40), of which the front braids were thrown forward on the chest and with the help of silver chains were placed on the back. Experienced braiders skillfully braided woolen threads in the color of the hair, decorating them with silver balls and brushes. Decorated with silver jewelry and felt hat in the shape of a fezka without a brush, it was hung on chains in the front by a number of newcomers, leaves, chains, amulets. The temples had hanging hangers – eresnots. In many areas, a silver flat with minted flowers, images of angels, and sunlight, among others, was sewn on the felt from above.

When she got married, the woman put on a red hat made of the thinnest felt, with a long brush of purple or blue twisted silk threads of 40 cm long, in the southern regions – "kotik", in Karina Shirak "vard" (literally rose).

All this elegant colorful complex was complemented by a lot of jewelry: necklaces, pendants, bracelets, rings, as well as a silver or gold-plated belt with a massive buckle of amazingly fine jewelry. Most of them were the property of wealthy Armenian women, especially in the trade and crafts environment in many cities of Western Armenia and Transcaucasia.[2]

Footwear

Since ancient times, footwear has been an integral part of traditional Armenian clothing. Men's and women's shoes (knitted socks and the actual shoes) were largely identical. Knitted patterned socks – Jorabs and gulpas, which, along with men's leggings, were known as early as the Urartian period and occupied an important place in Armenian footwear. In traditional everyday life, male and female patterned jorabs were knitted densely from the wool of a particular region. They could be monochromatic or multi-colored, with each region having its own favorite pattern and color. In the Ottoman Empire, Armenians and Jews were required to wear blue or purple shoes to denote their status as minorities. Later, Armenians had to wear red shoes to indicate to the Ottomans that they were Armenian.[5] They were widely used not only in everyday life, but also had ritual significance. Socks were part of the girl's dowry, and were one of the main objects of gift exchange at weddings and christenings. They were widespread throughout Armenia and remained in many areas until the 1960s.[2]

See also

Gallery

- Bridal dress from Shamakh, 19th century

- Cilician bride

- New Julfa taraz embroidered by hand, 16th to 17th century

- Chaharmahal woman

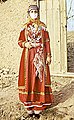

- Talin taraz

- Vostan taraz

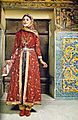

- During Bagratuni dynasty, featuring ermine, 9th to 12th century

- Syunik taraz, 18th century

- Kharberd taraz

- Shatakh (Vaspurakan) taraz with ornamented hat, teasels and plaits

- Taraz of Lower Hayk

- Bridal dress of Akhaltsikha, 19th century

- Armenian traditional clothing

- Girls in Armenian National Dress

- Armenian singer Sirusho in Vaspurakan Taraz for her "PreGomesh" music video

- Armenian men from Gyumri

- Traditional wedding ceremony of slaughtering a bull, early 20th century, Lori

- Armenian from Lake Van region

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i L. M. Vardanyan, G. G. Sarkisyan, A. E. Ter-Sarkisyants (2012). Armenians / otv. ed. Institute of Archeology and Ethnography of NAS RA. pp. 247–274. ISBN 978-5-02-037563-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Levon Abrahamian (2001). Nancy Sweezy (ed.). Armenian folk arts, culture, and identity. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253337047.

- ^ The Costumes of "Armenian Women" and "ARMENIA Crossroads of Culture- by Anahid V. Ordjanian

- ^ Patrick Arakel (1967). Armenian national clothing. Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Armenian SSR. page 16

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jill Condra (2013). "Armenia". Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing Around the World. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 31–43. ISBN 9780313376375.

- ^ Pardoe, Miss (Julia) (1836). The City of the Sultan; and Domestic Manners of the Turks. Cambridge University Press. p. 6. doi:10.1017/CBO9781107449954. ISBN 9781107449954.

- ^ Armenpress (29 July 2016). "Yerevan Taraz Fest to be held in Stepanakert". armenpress.am. Yerevan.

- ^ a b Avakyan N. H. Armenian folk clothes (19th and early 20th century). Yerevan, 1983. Pages 61–62

- ^ Аствацатурян, Э. Г. Оружие народов Кавказа, История оружия.

- ^ Alla Ervandovna Ter-Sarkisyanets "Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh", p. 628-629.

- ^ a b c d Lisician S. D. Essays on ethnography of pre-revolutionary Armenia // KES. 1955 Т. Я. С. 182–264

- ^ Arakel, Patrick (1967). Armenian Costume (in Armenian). Yerevan. p. 14.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Naapetyan R. And the family and family ritual of the Armenians of Akhdznik. Yerevan, 2004. С. 52

- ^ Arakel Patrick. Armenian clothing from ancient times to the present day. Research and drawings of Arakel Patrick's album. Yerevan, 1967

- ^ a b c d Avakyan N. H. Armenian folk clothes (19th – early 20th centuries). Yerevan

- ^ L.S. Gushchyan (1916). Treasures of Western Armenia. Ministry of Culture of the Russian Federation; Russian Museum of Ethnography. p. 52. ISBN 978-9939-9077-6-5.

Man's hat Arakhchi

- ^ Torlakyan, B.G. The Costume of the Hamshen Armenians at the End of the 19th Century (in Armenian).

- ^ Lisitsian S. D. Armenians of Zangezur. Yerevan, 1969. C. 116

- ^ Avakyan A. N. Gladzor School of Armenian Miniatures. Yerevan, 1971. С. 216

- ^ Lisician S. D. Essays on ethnography of pre-revolutionary Armenia // KES. 1955 Т. Я. С. 224–225

- ^ N. Avagyan N. H. Armenian folk clothes (19th and early 20th century). Yerevan, 1983. Page 19

- ^ Lisician S. D. Essays on ethnography of pre-revolutionary Armenia // KES. 1955 Т. Я. С. 227–230

- ^ Avakyan N. H. Armenian folk clothes (19th and early 20th century). Yerevan, 1983. Page 30

Notes

- ^ Western Armenian pronunciation: daraz

Further reading

- Chopoorian, Greg. "Continuity and Adaptation: The Changing Tale of Armenian Clothing.” Medieval History Magazine, 13 (September 2004): 29–35

- Derzon, Manoog. Village of Parchanj General History (1600–1937). Boston: Baikar Press, 1938.

- Hai Guin Society of Tehran. The Costumes of Armenian Women. Tehran: International Communicators, 1976.

- Lind-Sinanian, Gary. Armenian Folk Costumes, A Coloring Book for Children. Watertown, Ma: Armenian Library and Museum, 2004.

- Micklewight, Nancy. “Late-Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Wedding Costumes as Indicators of Social Change.” Muqarnas, 6 (1989): 161–174.

- Scarce, Jennifer. Women's Costume of the Near and Middle East. London: St. Edmundsbury Press, 2003.