Archaeology of Hatfield and Thorne

Over the past four decades, extensive research has been conducted on the Archaeology of Hatfield and Thorne Moors, resulting in the discovery of important Bronze Age and Neolithic trackways. These investigations have been carried out as part of wider initiatives to understand the complex and intertwined social-ecological-climatic systems that has shaped this region over the Holocene.[1] The current landscape has been heavily altered by humans, notably though drainage by Cornelius Vermuyden in the 17th century. This area is notable for its extensive palaeoecological work and serves as a model for other studies in environmental archaeology.[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Location

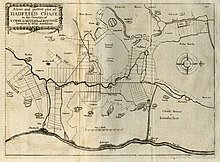

The Thorne and Hatfield Moors are within the Humberhead Levels and form part of the largest raised ombrotropic (or 'rain fed') peat mire in England. The sites are well known for their ecological significance nationally and internationally, and there are long-term management plans underway to begin to restore the peat. The rarity and importance of the ecological qualities of the site coincide with the age of the peatland and retrospective historical archaeological features, which have yet to be fully discovered, although recent excavations over the last 40 years have led to the significant finds of a Bronze Age trackway and most recently the Lindholme Neolithic Trackway, sometimes referred to as the Oliver Track after its discoverer. Hatfield and Thorne Moors are currently using conservation and management strategies to produce positive outcomes for the niche environments of the peat, the archaeological assets and ecologies with the aim to create a working balance between the different requirements.[9]

Archaeological History

Since the 1700s there has been considerable antiquarian interest in Thorne and Hatfield Moors. Literature shows throughout history that locals have taken an interest in the ancient charred cut wood stumps that began to appear from the peat extraction process'.[10] The earliest reference to archaeological records was by Abraham De la Pryme (1701) who noted the finding of bog oaks and Roman coins and as well as an assumed bog body from the region.

One of the most notable antiquarian source for the site is Hunter who gives a detailed description of the local histories and tales of the area, including an unproven find of a bog body in Hatfield.[11] John Tomlinson focused on the drainage and history of the region recording finds and the existence of the 15th century hermitage on Lindholme Island at the centre of Hatfield Moors.[12] There are several antiquarian sources for Thorne regarding the discoveries of Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age finds; which include early Bronze Age flints, Mesolithic Tranchet Axe, Neolithic Flint Flake, Mesolithic Flint Scatter, Neolithic Stone Axe, Palaeolithic burning and many more.[13][14] The Yorkshire Philosophical Society Annual Report of 1862 mentions the discovery of an undated sword within the Hatfield Chase region although a more specific location is unknown, the sword is believed to reside in the Yorkshire Museum donated by W. Coulman [11]

The Bronze Age Trackway was discovered in 1972 after findings from Turner.[15] Pollen analysis evidenced small temporary wood clearance during the Bronze Age that warranted investigation. The investigation revealed rough timbers of various sizes placed side by side to create a trackway. It is thought the trackway was created during primary phase forest clearance and in part due to the contemporary widespread flooding of the local area.[16]

The most recent find on Hatfield Moor is the Lindholme Neolithic Trackway discovered in 2004. The corduroy trackway has an average width of 3 m, but is 4 m wide in one area with rails positioned 1.9 m – 2.1 m apart. The trackway dates to approximately to 2900-2500 BC. Additionally it is the only site of its kind to be constructed of pine, which is a reflection of the local availability of this tree. It is thought the trackway was constructed in the earliest stages of peat growth in the area and as such is most likely a direct response to the swamping of a local routeway.[17][18] The Lindholme trackway was designated a scheduled monument by Historic England in 2017 [19]

Palaeoenvironmental research

The both moorlands have been the focus of vast palaeoenvironmental studies with some results published in journals, reports or monograph form. Palynological and archaeoentomological (Coleoptera) analyses account for most of the work on both moors to date, with significant plant macrofossil, peat humification and testate amoebae studies also included.[9] There are limited micromorphological analysis' regarding the interface between the pre-peat-land-surfaces and the base of the peat on the moors- primarily aimed at identifying evidence for the disturbance caused by forest clearance, ploughing, and other human activity enabling a comparison to be made. The results did not give a conclusive answer regarding the relationships between the two, however cryoturbation structures were discovered on Hatfield Moor indicating the freezing and thawing groundwater during the Devensian.[9] It also identified well-developed soil horizons beneath the peat on the northern side of the Lindholme ridge.[citation needed]

Thorne Moor showed evidence of faunal activity prior to the peat formation, as part of soils were able to support deciduous woodland prior to peat growth.[9] There have been analysis of the palynological sequences for Thorne Moor as well as radiocarbon dating for the pollen sequencing (and humification, plant macrossil and testate amoebae). Hatfield has seen more detailed research on Coleoptera in the form of complete sequences supported by radiocarbon dating [9]

There has been considerable contribution to the understanding of the palaeoenvironment of Hatfield and Thorne Moors- however the full potential of these surveys is to some extent restricted due to an incomplete understanding of the landscape context of the various sampling sites. There is a strong archaeological record of both peatlands from antiquarian sources which provide evidence of human activity within the area but there is a lack of surviving, material where the source is identified. The damage caused by the peat extraction may contribute to the lack of finds most recently however it may be because of lack of human presence. However, despite the effect of drainage and cutting the area still hold the potential for preservation of organic material, including archaeological features and artefacts.[20]

See also

- Environmental archaeology

- Humberhead Levels

- Thorne and Hatfield Moors

- North Lincolnshire

- South Yorkshire

- Cornelius Vermuyden

- Hatfield Neolithic Trackway

- Amcotts Moor Woman

- Bog bodies

External links

- [1]List of Historic Maps from the Humberhead Levels

References

- ^ "Project Background | RECONSTRUCTING THE 'WILDSCAPE'". 5 February 2024. Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2024.

- ^ Van De Noort, Robert; Ellis, S.; Chapman, Henry; University of Hull; English Heritage, eds. (1997). Wetland heritage of the Humberhead levels: an archaeological survey. Kingston upon Hull: Humber Wetlands Project, University of Hull. ISBN 978-0-85958-192-9.

- ^ Mansell, Lauren Joanne (2012). "Floodplain-mire Interactions and Palaeoecology: Implications for Wetland Ontogeny and Holocene Climate Change".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Smith, B.M. (1985). "A palaeoecological study of raised mires in the Humberhead Levels".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Smith, Brian M. (2002). A Palaeoecological Study of Raised Mires in the Humberhead Levels. University of Michigan Press.

- ^ Kirby, Jason Robert (1999). "Holocene floodplain vegetation dynamics and sea-level change in the lower Aire valley, Yorkshire".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Gearey, B. R.; Marshall, P.; Hamilton, D. (2009). "Correlating Archaeological and Palaeoenvironmental Records using a Bayesian Approach: A Case Study from Sutton Common, South Yorkshire, England". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (7): 1477–1487. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.03.003.

- ^ Gearey, B. R. (2007). "Palaeoenvironment". 154. Council for British Archaeology.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f Chapman H P; Geary B R (2013). Modelling archaeology and palaeoenvironments in wetlands: The hidden landscape archaeology of Hatfield and Thorne Moors, eastern England. Oxbow Books. ISBN 9781782971740.

- ^ Abraham de Pryme 1701 cited in Buckland (1979). Thorne Moors: A Palaeological Study of a Bronze Age Site: A contribution of the history of the British Insect fauna

- ^ a b Hunter (1828). Classical Country Histories: South Yorkshire, republished (1974)EP Publishing

- ^ Tomlinson (1882) cited by Chapman and Geary (2014).Modelling Archaeology and Paleoenvironments in Wetlands

- ^ South Yorkshire HER

- ^ The Yorkshire Archaeological Journal (1973/4). VOL 45/46

- ^ 1965 cited in Buckland (1979). Thorne Moors: A Palaeological Study of a Bronze Age Site: A contribution of the history of the British Insect fauna

- ^ Buckland (1979). Thorne Moors: A Palaeological Study of a Bronze Age Site: A contribution of the history of the British Insect fauna

- ^ Chapman and Geary (2005). A Neolithic Trackway on Hatfield Moors – a significant discovery, "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), [PDF], accessed 7 December 2015 - ^ University of Birmingham (2015).Hatfield Trackway and Platform, Hatfield Moors, South Yorkshire, http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/historycultures/departments/caha/news/projects/environmental/hatfield.aspx, [www.doc], accessed 7 December 2015

- ^ Historic England. "Lindholme Neolithic timber trackway and platform, Hatfield (1443481)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ^ Coles and Coles 1996 cited in Chapman and Geary (2014)Modelling Archaeology and Paleoenvironments in Wetlands