Competition law theory

Competition law theory covers the strands of thought relating to competition law or antitrust policy.

Classical perspective

The classical perspective on competition was that certain agreements and business practice could be an unreasonable restraint on the individual liberty of tradespeople to carry on their livelihoods. Restraints were judged as permissible or not by courts as new cases appeared and in the light of changing business circumstances. Hence the courts found specific categories of agreement, specific clauses, to fall foul of their doctrine on economic fairness, and they did not contrive an overarching conception of market power. Earlier theorists like Adam Smith rejected any monopoly power on this basis.

"A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly under-stocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate."[1]

In The Wealth of Nations (1776) Adam Smith also pointed out the cartel problem, but did not advocate legal measures to combat them.

"People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public, or in some contrivance to raise prices. It is impossible indeed to prevent such meetings, by any law which either could be executed, or would be consistent with liberty and justice. But though the law cannot hinder people of the same trade from sometimes assembling together, it ought to do nothing to facilitate such assemblies; much less to render them necessary."[2]

Smith also rejected the very existence of, not just dominant and abusive corporations, but corporations at all.[3]

By the latter half of the nineteenth century, it had become clear that large firms had become a fact of the market economy. John Stuart Mill's approach was laid down in his treatise On Liberty (1859).

"Again, trade is a social act. Whoever undertakes to sell any description of goods to the public, does what affects the interest of other persons, and of society in general; and thus his conduct, in principle, comes within the jurisdiction of society... both the cheapness and the good quality of commodities are most effectually provided for by leaving the producers and sellers perfectly free, under the sole check of equal freedom to the buyers for supplying themselves elsewhere. This is the so-called doctrine of Free Trade, which rests on grounds different from, though equally solid with, the principle of individual liberty asserted in this Essay. Restrictions on trade, or on production for purposes of trade, are indeed restraints; and all restraint, qua restraint, is an evil..."[4]

Neo-classical synthesis

After Mill, there was a shift in economic theory, which emphasised a more precise and theoretical model of competition. A simple neo-classical model of free markets holds that production and distribution of goods and services in competitive free markets maximizes social welfare. This model assumes that new firms can freely enter markets and compete with existing firms, or to use legal language, there are no barriers to entry. By this term economists mean something very specific, that competitive free markets deliver allocative, productive and dynamic efficiency. Allocative efficiency is also known as Pareto efficiency after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto and means that resources in an economy over the long run will go precisely to those who are willing and able to pay for them. Because rational producers will keep producing and selling, and buyers will keep buying up to the last marginal unit of possible output - or alternatively rational producers will be reduce their output to the margin at which buyers will buy the same amount as produced - there is no waste, the greatest number wants of the greatest number of people become satisfied and utility is perfected because resources can no longer be reallocated to make anyone better off without making someone else worse off; society has achieved allocative efficiency. Productive efficiency simply means that society is making as much as it can. Free markets are meant to reward those who work hard, and therefore those who will put society's resources towards the frontier of its possible production.[5] Dynamic efficiency refers to the idea that business which constantly competes must research, create and innovate to keep its share of consumers. This traces to Austrian-American political scientist Joseph Schumpeter's notion that a "perennial gale of creative destruction" is ever sweeping through capitalist economies, driving enterprise at the market's mercy.[6]

Contrasting with the allocatively, productively and dynamically efficient market model are monopolies, oligopolies, and cartels. When only one or a few firms exist in the market, and there is no credible threat of the entry of competing firms, prices raise above the competitive level, to either a monopolistic or oligopolistic equilibrium price. Production is also decreased, further decreasing social welfare by creating a deadweight loss. Sources of this market power are said to include the existence of externalities, barriers to entry of the market, and the free rider problem. Markets may fail to be efficient for a variety of reasons, so the exception of competition law's intervention to the rule of laissez faire is justified. Orthodox economists fully acknowledge that perfect competition is seldom observed in the real world, and so aim for what is called "workable" or "effective competition".[7][8][9] This follows the theory that if one cannot achieve the ideal, then go for the second best option[10] by using the law to tame market operation where it can.

Chicago School

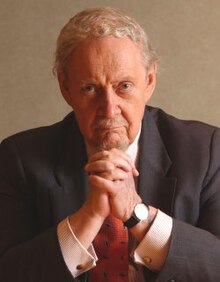

A group of economists and lawyers, who are largely associated with the University of Chicago, advocate an approach to competition law guided by the proposition that some actions that were originally considered to be anticompetitive could actually promote competition. The US Supreme Court has used the Chicago School approach in several recent cases.[11] One view of the Chicago School approach to antitrust is found in United States Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Richard Posner's booksAntitrust law[12] and Economic Analysis of Law[13] Posner once worked in the Department of Justice's antitrust division, has long been a professor at the University of Chicago Law School, and is likely the most widely cited antitrust scholar and jurist in the United States.[14]

Robert Bork was highly critical of court decisions on United States antitrust law in a series of law review articles and his book The Antitrust Paradox.[15] Bork argued that both the original intention of antitrust laws and economic efficiency was pursuit only of consumer welfare, the protection of competition rather than competitors.[16] Furthermore, only a few acts should be prohibited, namely cartels that fix prices and divide markets, mergers that create monopolies, and dominant firms pricing predatorily, while allowing such practices as vertical agreements and price discrimination on the grounds that it did not harm consumers.[17] Running through the different critiques of US antitrust policy is the common theme that government interference in the operation of free markets does more harm than good.[18] "The only cure for bad theory", writes Bork, "is better theory".[16] The late Harvard Law School Professor Phillip Areeda, who favours more aggressive antitrust policy, in at least one Supreme Court case challenged Robert Bork's preference for non intervention.[19]

Other critiques

Some economic libertarians have criticised competition law in its entirety, challenging the legitimacy of action against price fixing and cartels.[20]

See Dominic Armentaro "Antitrust: The Case for Repeal" (Ludwig Von Mises Institute 1986) and "The Case Against Antitrust" by Robert A. Levy (Cato Institute 2004). The case being that "competition law" (or "Antitrust") is based upon a false view of economics - that it harms rather than benefits consumers in the long term. And that "competition law" (or "Antitrust") is based upon principles of law and philosophy that are both false and confused.

Policy developments

Anti-cartel enforcement is a key focus of competition law enforcement policy. In the United States the Antitrust Criminal Penalty Enhancement and Reform Act 2004 raised the maximum imprisonment term for price fixing from three to ten years, and the maximum fine from $10 million to $100 million.[21] In 2007 British Airways and Korean Air pleaded guilty to fixing cargo and passenger flight prices.[22]

These actions complement the private enforcement which has always been an important feature of United States antitrust law. The United States Supreme Court summarised why Congress allows punitive damages in Hawaii v. Standard Oil.[23]

"Every violation of the antitrust laws is a blow to the free-enterprise system envisaged by Congress. This system depends on strong competition for its health and vigor, and strong competition depends, in turn, on compliance with antitrust legislation. In enacting these laws, Congress had many means at its disposal to penalize violators. It could have, for example, required violators to compensate federal, state, and local governments for the estimated damage to their respective economies caused by the violations. But, this remedy was not selected. Instead, Congress chose to permit all persons to sue to recover three times their actual damages every time they were injured in their business or property by an antitrust violation."

In the EU, the Modernisation Regulation 1/2003 means that the European Commission is no longer the only body capable of public enforcement of European Community competition law. This was done in order to facilitate quicker resolution of competition-related inquiries. In 2005 the Commission issued a Green Paper on Damages actions for the breach of the EC antitrust rules,[24] which suggested ways of making private damages claims against cartels easier.[25]

See also

- Competition policy

- Consumer protection

- Herfindahl-Hirschman Index in market structure

- History of economic thought

- SSNIP

- Relevant market

- European Community competition law

- Irish Competition law

Notes

- ^ Smith (1776) Book I, Chapter 7, para 26

- ^ Smith (1776) Book I, Chapter 10, para 82

- ^ Smith (1776) Book V, Chapter 1, para 107

- ^ Mill (1859) Chapter V, para 4

- ^ for one of the opposite views, see Kenneth Galbraith, The New Industrial State (1967)

- ^ Joseph Schumpeter, The Process of Creative Destruction (1942)

- ^ Whish (2003) p.14

- ^ Clark, "Towards a Concept of Workable Competition" (1940) 30 Am Ec Rev p.241-256

- ^ Markham, "An Alternative Approach to the Concept of Workable Competition" (1950) 40 Am Ec Rev p.349-361

- ^ c.f. Lipsey and Lancaster, "The General Theory of Second Best" (1956-7) 24 Rev Ec Stud 11-32

- ^ Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania Inc., 433 U.S. 36 (1977), Broadcast Music Inc. v. Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., NCAA v. Board of Regents of Univ. of Oklahoma, Spectrum Sports Inc. v. McQuillan, State Oil Co. v. Khan, Verizon v. Trinko, and Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc. v. PSKS, Inc.

- ^ Posner, Antitrust Law (2001) 2nd ed., ISBN 978-0-226-67576-3

- ^ Posner, Economic Analysis of Law (2007) 7th ed., ISBN 978-0-7355-6354-4

- ^ Posner (2001) p.24-25

- ^ Bork, Robert H. The Antitrust Paradox (1978) New York Free Press ISBN 0-465-00369-9

- ^ a b Bork (1978) p.405

- ^ Bork (1978) p.406

- ^ Frank Easterbrook, The Limits of Antitrust, 63 U. Tex. L. Rev. 1 (1984).

- ^ Brooke Group v. Williamson 509 US 209 (1993)

- ^ For a criticism of the libertarian view see Michael E. DeBow (2007) What's Wrong with Price Fixing: Responding to the New Critics of Antitrust, published by the Cato Institute Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ see generally, Pate (2004) at USDOJ

- ^ see, USDOJ Antitrust's press release Archived 2007-08-08 at the Wayback Machine and the court filing

- ^ Hawaii v. Standard Oil Co. of California 405 U.S. 251, 262 (1972)

- ^ Damages actions for the breach of the EC antitrust rules {SEC(2005) 1732} /* COM/2005/0672

- ^ see FAQ on the Green paper here

References

- Bork, Robert H. (1978) The Antitrust Paradox, New York Free Press ISBN 0-465-00369-9

- Bork, Robert H. (1993). The Antitrust Paradox (second edition). New York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-904456-1.

- Friedman, Milton (1999) The Business Community's Suicidal Impulse

- Galbraith Kenneth (1967) The New Industrial State

- Mill, John Stuart (1859) On Liberty online at the Library of Economics and Liberty

- Posner, Richard (2001) Antitrust Law, 2nd ed., ISBN 978-0-226-67576-3

- Posner, Richard (2007) Economic Analysis of Law 7th ed., ISBN 978-0-7355-6354-4

- Prosser, Tony (2005) The Limits of Competition Law, ch.1

- Schumpeter, Joseph (1942) The Process of Creative Destruction

- Smith, Adam (1776) An Enquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

- Wilberforce, Richard (1966) The Law of Restrictive Practices and Monopolies, Sweet and Maxwell

- Whish, Richard (2003) Competition Law, 5th Ed. Lexis Nexis Butterworths

Further reading

- Elhauge, Einer; Geradin, Damien (2007) Global Competition Law and Economics, ISBN 1-84113-465-1