Amsterdam Metro

The Amsterdam Metro (Dutch: Amsterdamse metro) is a rapid transit system serving Amsterdam, Netherlands, and extending to the surrounding municipalities of Diemen and Ouder-Amstel. Until 2019, it also served the municipality of Amstelveen, but this route was closed and converted into a tram line. The network is owned by the City of Amsterdam and operated by municipal public transport company Gemeente Vervoerbedrijf (GVB), which also operates trams, free ferries and local buses.

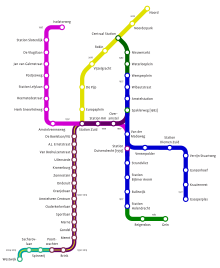

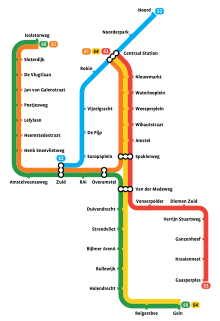

The metro system consists of five routes and serves 39 stations, with a total length of 42.7 kilometers (26.5 mi). Three routes start at Amsterdam Centraal: Route 53 and Route 54 connect the city centre with the suburban residential towns of Diemen, Duivendrecht and Amsterdam-Zuidoost (the city's southeastern borough), while Route 51 first runs south and then follows a circular route connecting the southern and western boroughs. Route 50 connects Zuidoost to the Amsterdam-West borough using a circular line, which it shares with Route 51. It is the only route that does not cross the city centre. A fifth route, Route 52, running from the Amsterdam-Noord (north) borough to Amsterdam-Zuid (south) via Amsterdam Centraal, came into operation on 21 July 2018. As opposed to the other routes, it runs mostly through bored tunnels and does not share tracks with any other route.

History

Planning history

The first plans for an underground railway in Amsterdam date from the 1920s: in November 1922, members of the municipal council of Amsterdam Zeeger Gulden and Emanuel Boekman asked the responsible alderman Ter Haar to study the possibility of constructing an underground railway in the city, in response to which the municipal department of Public Works drafted reports with proposals for underground railways in both 1923 and 1929. These plans stalled in the planning phase, however, and it took until the 1950s for the discussion about underground rail to resurface again in Amsterdam.[7][8]

The post-war population boom and increase in motorized traffic shifted the perception of underground rail transport in Amsterdam considerably: whereas in the 1920s, underground rail had been considered too expensive, halfway through the 1950s it was presented as a realistic solution to the problems caused by increased traffic. In 1955, a report published by the municipal government concerning the inner city of Amsterdam—known by the Dutch title Nota Binnenstad—suggested installing a commission to explore solutions to the traffic problems Amsterdam faced. This commission, which was headed by former director of the department of Public Works J.W. Clerx, was subsequently installed in March 1956, and published its report Openbaar vervoer in de agglomeratie Amsterdam in 1960.[9]

The aldermen and mayor of Amsterdam agreed with the conclusion of the report of the Clerx commission that an underground railway network ought to be built in Amsterdam in the near future. In April 1963 they installed the Bureau Stadsspoorweg which had the task to study the technical feasibility of a metropolitan railway, to propose a route network, to suggest the preferred order of construction of the various lines, and to study the adverse effects of constructing a metro line, such as traffic disruption and the demolition of buildings.[10]

In 1964 and 1965, Bureau Stadsspoorweg presented four reports to the municipal government of Amsterdam, which were made available to the public on 30 August 1966.[11] In March 1968, the aldermen and mayor of Amsterdam subsequently submitted a proposal to the municipal council of Amsterdam to agree to the construction of the metro network, which the council assented to on 16 May 1968 with 38 votes in favour and 3 against.[6] Under the original plan, four lines were to be built, connecting the entire city and replacing many of the existing tram lines. The following lines were planned: an east–west line from the southeast to the Osdorp district via Amsterdam Centraal railway station; a circle line from the western harbor area to the suburban town of Diemen; a north–south line from the northern district via Amsterdam Centraal to Weteringplantsoen traffic circle, with two branches at both ends; and a second east–west line from Geuzenveld district to Gaasperplas. The system would be constructed gradually and was expected to be completed by the end of the 1990s.[12]

Design and construction

The first part of the original plan to be carried out was the construction of the Oostlijn (East Line), which started in 1970. The East Line links the city centre with the large-scale Bijlmermeer residential developments in the south-east of the city. It opened in 1977. The East Line starts underground, crossing the city centre and adjacent neighbourhoods in the eastern districts until Amsterdam Amstel railway station, where it continues above ground in southeastern direction. At Van der Madeweg metro station, the line splits into two branches: the Gein Branch for Route 54 and Gaasperplas Branch for Route 53. Since 1980, the northern terminus for both routes is Amsterdam Centraal railway station.

Ben Spangberg, an architect from the Government of Amsterdam, was asked to design the stations on the line. After two years of work, he told that it was too much for one person, and Sier van Rhijn was assigned to the project as well.[13] Spangberg said that they avoided sharp corners and used smooth designs instead. He wanted to have elevators in all stations, but initially wasn't allowed due to cost issues and because Nederlandse Spoorwegen didn't want to stay behind. After further discussions, the architects were permitted to design two elevator shafts, with only one of them active.[14] Construction on the tunnels started while the stations were still being designed. The architects frequently visited the construction sites to instruct the workers to do something specific to allow for possible changes in the future.[15] Most underground areas of the line were built by using 40 metres (131 ft 3 in) long caissons. The caissons were built on the spot and lowered into their place by blasting away the soil beneath.[16] This method required the demolition the houses above the tunnel.[17] The Wibautstraat station and the tunnels near it were constructed differently, using the cut-and-cover method.[18]

During the construction of the metro tunnel, the decision to demolish the Nieuwmarkt neighbourhood in the city centre led to strong protests in the spring of 1975 from action groups consisting of locals and members of the highly active Amsterdam squatting movement. Wall decorations at the Nieuwmarkt metro station are a reference to the protests, which are known as the Nieuwmarkt riots (Nieuwmarktrellen).[19] Despite the protests, construction of the metro line continued but plans to build a highway through the area were abandoned. In addition, the original plans for an east–west metro line were cancelled. One of the sites where this line was to connect with the East Line had already been built underneath Weesperplein station. This lower level of Weesperplein station was never opened to the public, but its existence can still be noticed by the elevator buttons. Since the East Line was planned and built during the Cold War, Weesperplein station also features a bomb shelter which has never been used as such.[20]

Later lines

In 1990, the Amstelveenlijn (Amstelveen Line) was opened, which is used for Route 51. Under a political compromise between the city of Amsterdam and the municipality of Amstelveen, the northern section of the line was built as a metro line while the southern section is an extended tram line. Therefore, Route 51 was originally referred to as a 'sneltram' (express tram) service, and the vehicles were manufactured to light rail standards. The changeover between third rail and overhead tramline power took place at Zuid Station.

From March 2019 onwards, the Amstelveenlijn as a sneltram ceased to exist, and is being replaced by a tram line terminating at Zuid station, including a €300 million rebuild of the original line. For connection to the metro, passengers will have to transfer at Zuid station.[21] Line number 51 was retained for a new circular line between Isolatorweg and Central Station.

In 1997, the Ringlijn (Ring Line), which is used for Route 50, was added to the system. The line provides a rapid transit connection between the south and the west of the city, eliminating the necessity of crossing the city centre.

In 2018, the Noord-Zuidlijn (North–South Line) was added to the network. The line provides a fast connection from the north of the IJ waterway to the south of Amsterdam.

Network

From 1997 to 2018 the Amsterdam metro system consisted of four metro routes. The oldest routes are Route 54 (from Centraal station to Gein) and Route 53 (from Centraal station to Gaasperplas). Both routes are using the Oostlijn (East Line) infrastructure, which was completed in 1977. Route 51 (from Centraal station to Amstelveen Westwijk), using part of the East Line as well as the Amstelveenlijn (Amstelveen Line), was added in 1990. Route 50 (from Isolatorweg to Gein) using the Ringlijn (Ring Line or Circle Line), which was completed in 1997, as well as part of the East Line infrastructure.

A fifth line, Route 52 (from Noord station to Zuid station), was added to the network operating the Noord-Zuidlijn (North–South Line), which was completed and opened on 21 July 2018.[22]

There are 33 full metro stations,[1] Since Route 52 on the new North-South Line opened, six additional stations and 9.5 kilometres (5.9 mi) of route have been added to the metro system,[23] yielding a new combined network length of 52 kilometres (32 mi).[24] In 2019, sneltram Route 51 no longer operates into the metro network. The southern sneltram portion was closed for conversion to be incorporated into the tram network.[25]

| Colour | Route | Symbol | Line(s) | Line(s) used | Termini | Opening | Length | Stations | Passengers/day (2019 average) | Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| green | Line 50 | Ring Line, East Line (Gein branch) | Isolatorweg – Gein | 1997 | 20.1 km (12.5 mi)[5] | 20 | 100,200 | Metro | ||

| orange | Line 51 | Ring Line, East Line | Isolatorweg – Centraal Station | 1990 | 19.5 km (12.1 mi)[5] | 19 | 60,800 | |||

| blue | Line 52 | North–South Line | Noord – Zuid | 2018 | 9.5 km (5.9 mi)[23] | 8 | 84,000[2] | |||

| red | Line 53 | East Line (Gaasperplas branch) | Gaasperplas – Centraal Station | 1977 | 11.3 km (7.0 mi)[5] | 14 | 60,600 | |||

| yellow | Line 54 | East Line (Gein branch) | Gein – Centraal Station | 12.1 km (7.5 mi) | 15 | 73,500 |

East Line (Routes 53 and 54)

Route

On 14 October 1977, the first metro train ran on the Oostlijn (East Line) from Weesperplein to Amsterdam-Zuidoost, with two branches respectively going to Gaasperplas (now Route 53) and Holendrecht (now Route 54). Spaklerweg station was completed as a shell, but opened later. On 11 October 1980, both routes were extended to Amsterdam Centraal Station, which is now their northern terminus. The Gein Branch was extended in the southern direction on 27 August 1982, when the section between Holendrecht and Gein was completed. Spaklerweg station was then opened. In some plans for the Gein Branch, an extension to Weesp and Almere was being considered. According to the most recent regional planning study, that now seems unlikely.[26]

Architecture

A notable part of the East Line infrastructure is a dual metro overpass on the Gaasperplas Branch in the Bijlmermeer district between Ganzenhoef and Kraaiennest stations. This 1,100-metre (3,608 ft 11 in) long colonnade contains two single crossovers, each consisting of 33 pillars carrying 33-metre (108 ft 3 in) long beams. The center-to-center distance between the two overpasses is 15 metres (49 ft 3 in). This exceptional height was necessary because the metro had to bridge the main thoroughfares in the Bijlmermeer district which were built on a system of raised embankments and viaducts.

The stations, the infrastructure and the Diemen-Zuid maintenance facility of the East Line were designed by Ben Spängberg and Sier van Rhijn, two architects at the former Public Works Department of the City of Amsterdam. Their designs in Brutalist style are characterized by large-scale application of bare concrete and excessive space in the underground station halls. It also included a sophisticated use of colour. For example, the red colour of the train doors in the original design was also used at major facilities such as billboards, gates, elevator doors, bins, and the platform signage. For the design of the entire East Line Spängberg and Van Rhijn received Merkelbach Award in 1979. The East Line was also awarded the Betonprijs (Concrete Award) in 1981, which is commemorated by the award plaques in the concourses of Centraal station and Gein station.

As part of the city's policy that one percent of construction budgets for public works had to be spent on art, all stations on the Oostlijn have been decorated by different artists. In addition, the western wall of the tunnel was painted with lines and patterns which altered between the two stations, providing passengers with a fascinating view during the ride. Over the years, these decorations have completely been covered with graffiti. Some of the station artworks have also disappeared. Plans to remove all artworks as part of the large-scale renovation of the East Line tunnel in 2012 were altered after citizens' protests stating their historical significance.[27][28]

Renovation

Over the years, several stations along the East Line were expanded or renovated. Since 2003, the metro station at Amsterdam Centraal station has been continuously under construction in order to accommodate the new North–South Line station. As part of commercial development of the area surrounding the Amsterdam Arena football stadium, which included a new major business and shopping district, the Bijlmer Arena station was substantially enlarged in order to handle the increasing number of passengers. The new station, designed by Grimshaw and Arcadis Articon Architects, opened in 2007 and was shortlisted for the Stirling Prize of the Royal Institute of British Architects.[29] Another East Line station, Kraaiennest on Route 53, was reconstructed and upgraded in 2013 as part of the major urban renewal efforts in the Bijlmermeer district. The station designed by Maccreanor Lavington features a stainless steel facade with a floral design, which, according to the architects, "allows the station to be a lantern for the local neighbourhood, creating a sense of warmth on street level and creating an instantly recognisable feature for the station" at night time.[30] The design was awarded the 2014 EU Stirling Prize.[31][32]

A major overhaul of sixteen East Line stations was announced in June 2014. The renovation works taking place from 2015 until 2017 should bring more light and space to the stations. By removing paint layers on the walls, the original Brutalist architecture will become more pronounced. In addition, disused ticket offices are to be removed and lighting and signage will be improved.[33][34]

Amstelveen Line (former route 51)

History

Following the Nieuwmarkt Riots in 1975, the next major expansion of the metro network into the bordering city of Amstelveen was politically sensitive. When the decision was made to begin construction of the Amstelveenlijn (Amstelveen Line) in 1984, it was originally considered an express tram service rather than a fully-fledged metro route. On 1 December 1990 the section running from Spaklerweg to Poortwachter Station in Amstelveen was completed. As the sensitivity surrounding the metro expansion waned in the 1990s, the route was increasingly being referred to as a metro service. On 13 September 2004 an extension to Amstelveen Westwijk was completed.

Originally, the entire route of the Amstelveen Line from Spaklerweg, where it connects with the East Line, to Amstelveen was to be powered via overhead wiring. Eventually, it was decided to use a third rail between Spaklerweg and Zuid station in order to be able to increase metro service on this section of the line during exhibitions at the RAI convention centre, and overhead wiring on the southern section into Amstelveen.

The line was officially opened on 30 November 1990, replacing the overcrowded bus route 67. The equipment, lightrail series S1 and S2, was built between 1990 and 1994 by Belgian manufacturer BN in Bruges. From 1994, a total of 25 light rail vehicles was in operation. Since the extension to Westwijk in 2004, a number of S3 series trains are sometimes used on this route, raising the total number of vehicles available to 29.

Shortly before the opening, two lightrail vehicles had collided during trial runs, which reduced the number of vehicles available for the route to 11. Because of the lack of equipment and startup problems, the route was initially operated with limited service. In February 1991 heavy snowfall, continuing technical problems and equipment shortages led to the decision to limit the route to the route between Centraal Station and Zuid Station for nearly seven months, with replacement bus services on the remaining route into Amstelveen.

In 2018, after the completion of the Noord-Zuidlijn (North–South Line), there would be no more room at Amsterdam Zuid station for Route 51 to continue as express tram service into Amstelveen. According to a long-term regional planning study of 2011, the Amstelveenlijn was to be upgraded to a fully-fledged metro service.[26] On 12 March 2013, however, the regional council of the City Region of Amsterdam decided that Route 51 would be replaced by an improved express tram service running from Westwijk to Zuid Station and a separate metro service running from Zuid Station and Amstel Station. Passengers from Amstelveen would then be required to change at Zuid Station to the metro route for Amstel or to the new Route 52 for Centraal Station. It was also decided that Tram Route 5 would run between Amstelveen and Westergasfabriek.[35] Conversion of the southern section of the Amstelveen Line to tram operation started in 2016.[36][37]

On 3 March 2019, the Amstelveen branch (the hybrid metro/tram line) was cut from route 51 as the tunnel connecting the metro line with the tram network had to make way for an underground section of the A10 motorway. In December 2020, the Amstelveen Line would become tram line 25.[38]

Route

From Centraal Station to Amsterdam Zuid station, Route 51 ran as a full metro service and had no at-grade intersections. The light-rail vehicles on the line were powered by a third rail with the line being suitable for 3-metre (9 ft 10 in) wide trams. The BN vehicles, however, had a width of 2.65 metres (8 ft 8 in) which was the maximum width on the southern section of the line between Zuid Station and Westwijk. In order to bridge the gap between the trains and the platforms in northern section, the vehicles were equipped with retractable footboards at the doors. In addition, the vehicles were equipped with pantographs in order to retrieve power from the overhead wiring on the southern section. From Zuid Station to Westwijk, the route operated as an express tram service. On the northern half of this section, Route 51 shared tracks with Line 5 of the tramway, with dual height platforms provided at the stops shared by both lines.

Since 3 March 2019, the Amstelveen section of route 51 has been discontinued. Line 51 was upgraded to a full metro line and now runs between Central Station and Isolatorweg. Since December 2020, tram line 25 has been serving the route from Zuid Station to Westwijk.

Ring Line (Route 50)

Opened on 1 June 1997, the Ringlijn (Ring Line or Circle Line) is entirely built on embankments and viaducts, and has no level crossings. The line was initially for political reasons called "express circle tram", but since the opening of the Ring Line the transit service on the line is referred to as a Metro Route 50 (from Gein to Isolatorweg). Because it was originally considered a tram line, the light rail vehicle width of 2,65 meters was to be applied; the width that was also used on the Amstelveen Line. The new "trams" (Series M4 and S3) have retractable running boards to bridge the space between the vehicle and the platform at existing stations. Since Route 50 proved hugely popular, the express tram vehicles were insufficient to handle the number of passengers. Instead of ordering additional vehicles, in 2000 the city of Amsterdam decided to adjust the platforms at the stations between Amstelveenseweg and Isolatorweg, whereby the older rolling stock (M1, M2 and M3) serving on the East Line could also serve on the Ring Line. Such an operation was already taken into account during the construction of the stations.

North–South line (Route 52)

In 2002, the construction of the Noord/Zuidlijn (North–South line) was started. The new metro line is the first to serve the Amsterdam North district, via a tunnel under the IJ. From there, it runs via Amsterdam Centraal to Amsterdam Zuid, which is planned to become the second biggest transport hub in the city, after Amsterdam Centraal.[39] The line includes a mixture of bored tunnels and immersed tunnels under the IJ.[40]

The construction programme experienced several difficulties, mainly at Amsterdam Centraal, resulting in the project running more than 40% over budget and the opening being delayed several times. The project initially had a budget of €1.46 billion, but after several setbacks the total cost estimate has been adjusted to €3.1 billion (at 2009 prices). The original planned opening was for 2011, but eventually the line was opened on 21 July 2018.[41]

The North–South line might be extended to Amsterdam Airport Schiphol in the future.[39] In August 2014, it was announced that the line was to be equipped with 4G mobile phone coverage, to be funded jointly by the major mobile phone operators.[42]

Planned expansion

The tram line to IJburg in the east was originally planned to be a metro line. For this reason, a short tunnel was constructed eastwards from Centraal Station underneath the railway lines. As this line was eventually constructed for tram services, the tunnel was abandoned, and there are plans to use it as part of a chocolate museum.[43] There are still plans for the tram to IJburg to be upgraded to metro and connect to the nearby city of Almere.[44]

On completion of the north–south metro line, Amsterdam Municipality announced it was analysing a possible east–west line at a projected cost of €7 billion.[45]

In January 2019, CEO of Amsterdam Airport Schiphol Dick Benschop announced that agreements had been reached to extend the north–south line to the airport and Hoofddorp.[46] In June 2019, the province of North Holland outlined plans to extend the metro to Zaandam and Purmerend along with Schiphol and Hoofddorp.[47] A station box has already been constructed for a potential underground station in Sixhaven, on the north–south line between Noorderpark and Centraal, to be opened at a later date.[48]

Technology

Rolling stock

As of January 2016, there are 90 electric multiple unit train sets in use within the Amsterdam Metro system.[49] All use standard gauge track and operate on a 750 V DC third rail electrification system.

M1/M2/M3

The original, first-generation fleet consisted of types M1, M2 and M3, designed as four-axle, two-car sets manufactured by the German firm Linke-Hofmann-Busch and delivered between 1973 and 1980. These first-generation trains are nicknamed zilvermeeuw (herring gull) because of their body of unpainted steel creating a silvery look. In 2009, all trains were provided with a new interior design by different artists. As they are built to full metro carrying capacity, they were used mainly on the east line services, Routes 53 and 54, with occasional use on Route 50.

As they neared the end of their life cycle and spare parts no longer became available, the entire fleet of M1-M3 trains was gradually taken out of service permanently from 2012 to 2015, being replaced by the modern M5 trains. The last unit (No. 23) was retired after a farewell tour on 19 December 2015 and has been preserved as a heritage train. All the other units have been scrapped, with the last of these being scrapped in December 2015.[50]

S1/S2/S3/M4

Until the arrival of the new M5 units, the remainder of the fleet consisted of smaller, narrower two section, 6-axle units that could operate both on the main metro network and the light rail ("sneltram") line to Amstelveen. Types S1 and S2, manufactured by La Brugeoise et Nivelles in Belgium, were the first units to be produced for use on this new line. In service since 1990, they currently operate exclusively on Route 51, although they could technically also be used on other lines though this has never been done. These vehicles are equipped with both third rail shoes and pantographs, along with retractable footboards to bridge the gap between the trains and the platforms on sections built to full metro standards. They are due to be withdrawn by 2020 with the conversion of the Amstelveen line to express tram service.

Types M4 and S3 were built by CAF in Spain to expand the fleet and have been in service since 1997. Type M4 was built for the new Ring Line service to Isolatorweg and is hence only third rail equipped. They mainly operate on Route 50 but can also be found on Routes 53 and 54, but never on route 51 due to their lack of pantographs. Four vehicles of the same design, designated type S3, have been equipped with pantographs to also serve on Route 51, but these rarely appear on other lines. As the platforms on the Ring Line were originally built to a smaller loading gauge than those on Routes 53 and 54, M4 and S3 sets were also equipped with retractable footboards to permit boarding on the section that Route 50 shares with Route 54. When the platforms on the Ring Line were narrowed to accommodate the older but wider M1-M3 sets, the boards were permanently removed on all M4 sets, but not on the S3 sets due to the limited loading gauge of the Amstelveen line.

M5

A newer addition to the Amsterdam Metro fleet is the M5 series, manufactured by the Polish manufacturer Alstom Konstal based on its Metropolis family of high-capacity metro trains, variants of which are in use in several foreign metro systems. Delivered from June 2013 onwards, the M5 series departs radically from previous generation units by coming in six-car articulated sets with gangway connections between all cars. Although the trains are suitable for unmanned service, they remain controlled by drivers for the time being. However, the trains are compatible with Alstom's "Urbalis" communications-based train control system which will replace the current signalling system by 2017 and enable automatic train operation across the entire network.[needs update] The M4 sets have been similarly equipped with this system in early 2016.

The initial order of 28 M5 metro sets, each carrying up to 1,000 passengers, was placed to replace all M1-M3 sets on the East Line as well as to increase overall capacity on the generally overstretched metro network. As such, they are used on all routes except Route 51. For Route 52 on the North–South Line an option was taken on a second series of 12 trains which was originally designated M6. However, the GVB now refers to all trains of this type as the M5 series.[51]

M7

The newest addition to the Amsterdam Metro fleet is the M7 series, manufactured by the Spanish manufacturer CAF, which entered passenger service on February 28, 2023. Onwards, the M7 series departs radically from previous generation M5 units by coming in three-car articulated sets with gangway connections between all cars.

The initial order of 30 M7 metro sets, was placed to replace all S1-S2 in 2024, and S3-M4 in 2027. As such, they are used on line 50, and later on 53 and 54.

Summary

| Vehicle | Type | Description[52] | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Series M1, M2, and M3 Full metro units for operation on Route 50 (mostly m4/S3), 53 and 54 Built by LHB (44 units total[citation needed]) |

Cars per unit: 2 Length: 37.5 m (123 ft 3⁄8 in) Width: 3.0 m (9 ft 10+1⁄8 in) Weight (fully loaded): 54 t (119,000 lb) Maximum speed: 70 km/h (43 mph) Power: 4 x 195 kW DC power supply: 750 volts |

1977–2015 |

|

Series S1 and S2 Hybrid metro/tram units for operation on Route 51 Built by BN (25 units total) |

Cars per unit: 2 Length: 30.6 m (100 ft 4+3⁄4 in) Width: 2.65 metres (8 ft 8+3⁄8 in) Weight (fully loaded):48.5 t (107,000 lb) Maximum speed: 70 km/h (43 mph) Power: 6 x 77 kW DC power supply: 600/750 volts |

1990–2024 |

|

Series S3 and M4 Light metro units for operation on Routes 50 and 51, sometimes operates on Route 53 Built by CAF (4 S3 units, 33 M4 units) |

Cars per unit: 2 Length: 30.9 m (101 ft 4+1⁄2 in) Width: 2.7 m (8 ft 10+1⁄4 in) Weight (fully loaded):48.0 t (105,800 lb) Maximum speed: 70 km/h (43 mph) Power: 6 x 70 kW DC power supply: 750 volts |

1997–present |

|

Series M5 Full metro units for Routes 50, 52, 53 and 54 Built by Alstom Konstal (28 units total) |

Cars per unit: 6 Length: 116.2 m (381 ft 2+3⁄4 in) Width: 3.0 m (9 ft 10+1⁄8 in) Weight: 190 t (420,000 lb) Maximum speed: 90 km/h (56 mph) Power: 16x200 kW DC power supply: 750 volts |

2013–present |

|

Series M7

Full metro units for Routes 50, 53 and 54 Built by CAF (30 units total) |

Cars per unit: 3 Length: 59.6 m (195 feet 629⁄64 in) |

2023–present |

Ticketing system

The OV-chipkaart, a nationwide contactless smart card system, is the only valid form of ticket on the metro system.[53] It replaced the so-called strippenkaart system on 27 August 2009, after the two systems had run parallel since 2006. Ticket barriers have been installed in all metro stations, with free-standing card readers where platforms are shared with train or tram lines. Amstelveen Line light rail stations are only equipped with free-standing card readers.

Graphic design

Signage on the Amsterdam metro system has featured multiple designs stemming from different eras. The original 1974 signage uses the M.O.L. typeface, which was specially designed for the metro by Gerard Unger. The openings within the letters are larger than normal in order to improve the letters' legibility when illuminated. The name M.O.L. refers to the Dutch word mol which means mole in English. The idea to use a mole as the mascot for the metro was rejected by city authorities.[54] Other versions are the 1991 version found on the Amstelveen Line, the 1995 version found mainly on Ring Line and the 2009 version which has replaced earlier versions at many stations. In 2016 the City Region of Amsterdam commissioned a new signage system and logo in an effort to harmonize all of the signage and wayfinding elements across all metro lines, in time for the renovation of the East Line and opening of the North-South Line.[55] The new design is based on the already-existing R-net branding, though somewhat modified.[56] It uses the Profile typeface and harks back to the original Unger design by using blue, white and red design elements. All of the wayfinding systems commissioned after the original 1974 one are designed by Mijksenaar.

- 1974 original design at Diemen Zuid station, featuring M.O.L. typeface

- 1991 style sign at Zonnestein station

- 1995 style sign at Isolatorweg station

- 2009 style sign at Bijlmer ArenA station

- 2016 style sign at Vijzelgracht station

Communications

A communications backbone for the Amsterdam Metro was installed by Thales, which is also responsible for associated maintenance.

Map

See also

Notes

- ^ a b "Maps - Metro stations overview". GVB. Archived from the original on 13 April 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ a b Duursma, Mark (26 September 2018). "Meer mensen met metro dan met tram door Noord/Zuidlijn". NRC. Archived from the original on 29 August 2021. Retrieved 22 August 2019.

- ^ "Jaarverslag 2018" [2018 Annual Report] (pdf) (in Dutch). GVB Holding NV. p. 45. Retrieved 22 June 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jaarverslag 2016" [Annual Report 2016] (in Dutch). GVB Holding NV. 23 May 2017. p. 18. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Network". GVB. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ a b Davids 2000, p. 158.

- ^ Jansen 1972.

- ^ Davids 2000, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Davids 2000, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Davids 2000, p. 164.

- ^ Davids 2000, pp. 165–166.

- ^ "Plan Stadsspoor" (PDF) (in Dutch). Communications Department, City of Amsterdam. 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Margreet Bosma (8 November 2012). "12 jaar lang aan de ontwerptafel van de Oostlijn. Interview met Ben Spängberg, architect". Wij Nemen Je Mee (in Dutch). Government of Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Margreet Bosma (13 November 2012). "Twaalf jaar lang aan de ontwerptafel van de Oostlijn– deel 2". Wij Nemen Je Mee (in Dutch). Government of Amsterdam. Archived from the original on 28 October 2022. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Margreet Bosma (8 November 2012). "12 jaar lang aan de ontwerptafel van de Oostlijn. Interview met Ben Spängberg, architect". Wij Nemen Je Mee (in Dutch). Government of Amsterdam. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ Ouwendijk 1977, p. 27.

- ^ Marc Kruyswijk (16 October 1977). "40 jaar metro: 'Zonder zou Amsterdam zijn vastgelopen'". Het Parool (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ Ouwendijk 1977, p. 28.

- ^ "Civil unrest, Nieuwmarkt ABC". Amsterdam City Archives. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Boondoggles: Unfinished metro station underneath Weesperplein junction". Jur Oster. 28 March 2013. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "AMSTELVEEN-LINE MAKEOVER – Amstelveen inzicht". Archived from the original on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 20 December 2018.

- ^ "Planning & Kosten". Noord/Zuidlijn (in Dutch). Gemeente Amsterdam [City of Amsterdam]. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Metronetstudie" [Metronet Study] (PDF) (in Dutch). Department of Infrastructure, Traffic and Transport, City of Amsterdam. 5 June 2007. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ "Metronetstudie" [Metronet Study] (PDF) (in Dutch). Department of Infrastructure, Traffic and Transport, City of Amsterdam. 5 June 2007. p. 93. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2014.

- ^ "Dutch start reconstruction of Amstelveen LRT". International Railway Journal. 5 March 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ a b "PlanAmsterdam: Structural Vision Amsterdam 2040" (PDF). Department of Physical Planning, City of Amsterdam. 2011.

- ^ "'Metrokunst waardevol voor stad' ('Metro art valuable for city')". FoliaWeb. 26 March 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Stations Oostlijn mogen (beschadigde) kunstwerken houden (East Line station keep their (damaged) art works)". Het Parool. 27 September 2012. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Bijlmer Station by Grimshaw". DeZeen Magazine. 9 September 2008. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Maccreanor Lavington overhauls Amsterdam's Kraaiennest metro station". DeZeen Magazine. 8 April 2014. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "The best new buildings – 2014 RIBA National Award winners are announced". Royal Institute of British Architects. 19 June 2014. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014.

- ^ "Amsterdam metro station is world famous for its architecture". DutchNews.nl. 29 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Stationsrenovatie Oostlijn (Station renovation East Line)" (in Dutch). Metro Department, City of Amsterdam. 25 June 2014.

- ^ "MetroMorphosis Amsterdam: Renovation of 18 metro stations on the Eastern Line". Zwarts en Jansma Architects. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Tram 5 vanaf 2018 naar Westergasfabriek)". rtva.nl. 1 June 2017. Archived from the original on 10 December 2018. Retrieved 10 December 2018.

- ^ "Persbericht: Regioraad stelt plannen voor ombouw Amstelveenlijn vast (Press notice: Regional council approves plans for conversion of Amstelveen Line)". Amstelveenlijn.nl. 12 March 2013. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Beschrijving voorkeursvariant Amstelveenlijn (Description Preferred Version Amstelveen Line), p. 12" (PDF). City Region of Amsterdam. 13 March 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Inge Jacobs (11 September 2019). "Vernieuwde Amstelveenlijn krijgt lijnnummer 25". OV Pro (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 16 November 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Zuidas Visie" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 June 2006. Retrieved 13 July 2006.

- ^ "Last section of Noord/Zuidlijn nears completion". Railway Gazette International. Archived from the original on 29 September 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- ^ "Planning en begroting" [Planning and Budgeting]. Noord/Zuidlijn (in Dutch). Gemeente Amsterdam [Municipality of Amsterdam]. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "New Amsterdam metro line to get 4G coverage". Telecompaper. 8 August 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2014.

- ^ "The biggest useless works of Amsterdam". Archived from the original on 24 December 2010. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "A Metro from Amsterdam to Almere (pdf)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "Amsterdam completes EUR 3.1 billion metro line". Railway PRO. 23 January 2018. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Amsterdam metro line to be extended to Schiphol airport". I Am Expat. 9 January 2019. Archived from the original on 29 July 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ "Provincie wil metro naar Zaandam, Purmerend, Hoofddorp en Schiphol". NH Nieuws (in Dutch). 12 June 2019. Archived from the original on 13 June 2019. Retrieved 17 November 2019.

- ^ "Amsterdam krijgt brug over het IJ". www.amsterdam.nl (in Dutch). 11 January 2017.

- ^ "Amsterdamse Metro (Metro Amsterdam)" (in Dutch). Dutch Wikipedia. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Laatste rit en afscheid Zilvermeeuw Metro GVB Amsterdam (Last ride and farewell of the "Herring gull" Metro GVB Amsterdam)" (in Dutch). Huey-dean van Eerde. 19 December 2015. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ "Nieuwe metro: de M5 Metropolis (New Metro: the M5 Metropolis)" (in Dutch). GVB. Archived from the original on 17 August 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ "Metro - Metro statistics". GVB. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "OV-Chip card in Amsterdam". Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "M.O.L. (1974)". Gerard Unger. Archived from the original on 10 December 2008. Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ "Wayfinding: nieuwe borden op metrostations - Stadsregio Amsterdam". www.stadsregioamsterdam.nl. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- ^ "'R-net' op onze metroborden; wat is het?". www.wijnmenjemee.nl. 21 January 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

References

- Davids, Carel (2000). "Sporen in de stad. De metro en de strijd om de ruimtelijke ordening in Amsterdam" (PDF). Tijdschrift Holland. 32 (3/4): 157–182. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- Jansen, L. (1972). "Een oud metroplan" (PDF). Ons Amsterdam. 24: 310–314. Retrieved 25 July 2017.

- Ouwendijk, Cees (October 1977). Een metro in Amsterdam (PDF) (in Dutch). Gemeente Vervoerbedrijf. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

External links

Media related to Metro, Amsterdam (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Metro, Amsterdam (category) at Wikimedia Commons- GVB – official website