Alexander II Zabinas

| Alexander II Zabinas | |

|---|---|

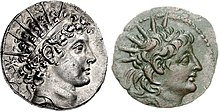

Alexander II's portrait on the obverse of a tetradrachm | |

| King of Syria | |

| Reign | 128–123 BC |

| Predecessor | Demetrius II |

| Successor | Cleopatra Thea, Antiochus VIII |

| Born | c. 150 BC |

| Died | 123 BC |

| Dynasty | Seleucid |

| Father | Probably Alexander I |

Alexander II Theos Epiphanes Nikephoros (Ancient Greek: Ἀλέξανδρος Θεὸς Ἐπιφανὴς Νικηφόρος Aléxandros Theòs Epiphanḕs Nikēphóros, surnamed Zabinas; c. 150 BC – 123 BC) was a Hellenistic Seleucid monarch who reigned as the King of Syria between 128 BC and 123 BC. His true parentage is debated; depending on which ancient historian, he either claimed to be a son of Alexander I or an adopted son of Antiochus VII. Most ancient historians and the modern academic consensus maintain that Alexander II's claim to be a Seleucid was false. His surname "Zabinas" (Ζαβίνας) is a Semitic name that is usually translated as "the bought one". It is possible, however, that Alexander II was a natural son of Alexander I, as the surname can also mean "bought from the god". The iconography of Alexander II's coinage indicates he based his claims to the throne on his descent from Antiochus IV, the father of Alexander I.

Alexander II's rise is connected to the dynastic feuds of the Seleucid Empire. Both King Seleucus IV (d. 175 BC) and his brother Antiochus IV (d. 164 BC) had descendants contending for the throne, leading the country to experience many civil wars. The situation was complicated by Ptolemaic Egyptian interference, which was facilitated by the dynastic marriages between the two royal houses. In 128 BC, King Demetrius II of Syria, the representative of Seleucus IV's line, invaded Egypt to help his mother-in-law Cleopatra II who was engaged in a civil war against her brother and husband King Ptolemy VIII. Angered by the Syrian invasion, the Egyptian king instigated revolts in the cities of Syria against Demetrius II and chose Alexander II, a supposed representative of Antiochus IV's line, as an anti-king. With Egyptian troops, Alexander II captured the Syrian capital Antioch in 128 BC and warred against Demetrius II, defeating him decisively in 125 BC. The beaten king escaped to his wife Cleopatra Thea in the city of Ptolemais, but she expelled him. He was killed while trying to find refuge in the city of Tyre.

With the death of Demetrius II, Alexander II became the master of the kingdom, controlling the realm except for a small pocket around Ptolemais where Cleopatra Thea ruled. Alexander II was a beloved king, known for his kindness and forgiving nature. He maintained friendly relations with John I Hyrcanus of Judea, who acknowledged the Syrian king as his suzerain. Alexander II's successes were not welcomed by Egypt's Ptolemy VIII, who did not want a strong king on the Syrian throne. Thus, in 124 BC an alliance was established between Egypt and Cleopatra Thea, now ruling jointly with Antiochus VIII, her son by Demetrius II. Alexander II was defeated, and he escaped to Antioch, where he pillaged the temple of Zeus to pay his soldiers; the population turned against him, and he fled and was eventually captured. Alexander II was probably executed by Antiochus VIII in 123 BC, ending the line of Antiochus IV.

Background

The death of the Seleucid king Seleucus IV in 175 BC created a dynastic crisis because of the illegal succession of his brother Antiochus IV. Seleucus IV's legitimate heir, Demetrius I, was a hostage in Rome,[note 1] and his younger son Antiochus was declared king. Shortly after the succession of young Antiochus, however, Antiochus IV assumed the throne as a co-ruler.[2] He may have had his nephew killed in 170/169 BC (145 SE (Seleucid year)).[note 2][4] After Antiochus IV's death in 164 BC, his son Antiochus V succeeded him. Three years later Demetrius I managed to escape Rome and take the throne, killing Antiochus V in 161 BC.[5] The Seleucid dynasty was torn apart by the civil war between the lines of Seleucus IV and Antiochus IV.[6]

In 150 BC Alexander I, an illegitimate son of Antiochus IV,[7] managed to dethrone and kill Demetrius I. He married Cleopatra Thea, the daughter of Ptolemy VI of Ptolemaic Egypt, who became his ally and supporter.[8] The Egyptian king changed his policy and supported Demetrius I's son Demetrius II, marrying him to Cleopatra Thea after divorcing her from Alexander I, who was defeated by his former father in law and eventually killed in 145 BC. The Egyptian king was wounded during the battle and died shortly after Alexander I.[9] His sister-wife and co-ruler, the mother of Cleopatra Thea, Cleopatra II, then married her other brother, Ptolemy VIII who became her new co-ruler.[10]

Diodotus Tryphon, Alexander I's official, declared the latter's son Antiochus VI king in 144 BC. Tryphon then had him killed and assumed the throne himself in 142 BC.[11] The usurper controlled lands in the western parts of the Seleucid empire, including Antioch,[9] but Demetrius II retained large parts of the realm, including Babylonia, which was invaded by the Parthian Empire in 141 BC.[12] This led Demetrius II to launch a campaign against Parthia which ended in his defeat and capture in 138 BC.[13] His younger brother Antiochus VII took the throne and married Demetrius II's wife. He was able to defeat Tryphon and the Parthians, restoring the lost Seleucid provinces.[14]

In Egypt, without divorcing Cleopatra II, Ptolemy VIII married her daughter by Ptolemy VI, Cleopatra III, and declared her co-ruler.[note 3][17] Cleopatra II revolted and took control over the countryside. By September 131 BC, Ptolemy VIII lost recognition in the capital Alexandria and fled to Cyprus.[18] The Parthians freed Demetrius II to put pressure on Antiochus VII, who was killed in 129 BC during a battle in Media.[19] This opened the way for Demetrius II to regain his throne and wife Cleopatra Thea the same year.[20] Ptolemy VIII returned to Egypt two years after his expulsion;[21] he warred against his sister Cleopatra II, eventually besieging her in Alexandria; she then asked her son-in-law Demetrius II for help, offering him the throne of Egypt.[20] The Syrian king marched against Egypt and by spring 128 BC, he reached Pelusium.[22]

In response to Demetrius II's campaign, Ptolemy VIII incited a rebellion in Syria.[22] The Syrian capital Antioch proclaimed a young son of Antiochus VII named Antiochus Epiphanes king, but the city was willing to change hands in such unstable political circumstances.[23] Ptolemy VIII sent Alexander II as an anti-king for Syria, forcing Demetrius II to withdraw from Egypt.[22] According to the third century historian Porphyry, in his history preserved in the work of his contemporary Eusebius, and also to the third century historian Justin, in his epitome of the Philippic Histories, a work written by the first century BC historian Trogus, Alexander II was a protégé of Ptolemy VIII.[note 4][27] The first century historian Josephus wrote the Syrians themselves asked Ptolemy VIII to send them a Seleucid prince as their king, and he chose Alexander II.[28] According to the Prologues of the Philippic Histories, the Egyptian king bribed Alexander II to oppose Demetrius II.[note 5][31]

Parentage and name

Alexander II was probably born in c. 150 BC.[note 6][33] His name is Greek, meaning "protector of men".[34] According to Justin, Alexander II was the son of an Egyptian trader named Protarchus.[35] Justin also added that "Alexander" was a regnal name bestowed upon the king by the Syrians.[36] Justin further stated that Alexander II produced a fabricated story claiming he was an adopted son of Antiochus VII.[37] Porphyry presented a different account in which Alexander II was claimed to be the son of Alexander I.[38]

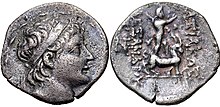

Modern historic research prefers the detailed account of Justin regarding Alexander II's claims of paternity and his connection to Antiochus VII.[37] However, a 125 BC series of gold staters minted by Alexander II had his epithets,[39] the same ones used by King Antiochus IV, father of Alexander I, and arranged in the same order they had on Antiochus IV's coins. Zeus carrying a Nike is depicted on the reverse of the stater; the Nike is carrying a wreath which crowns the epithet Epiphanes, an element featured in Antiochus IV's coinage.[40] Many themes of Antiochus IV's line appeared on Alexander II's coinage, such as the god Dionysus which was used by Alexander I in 150 BC,[41] in addition to the lion scalp, another theme in Alexander I's coinage.[42] Furthermore, Alexander II was depicted wearing the radiate crown; six rays protrude from the head and are not attached to the diadem, which is a theme that characterized all portraits of Antiochus VI when depicted wearing the radiate crown.[43] Based on those arguments, the account of Porphyry regarding Alexander II's claim of descent from Alexander I should be preferred to the account of Justin.[36][42][40]

Surname and legitimacy

Popular surnames of Seleucid kings are never found on coins, but are handed down only through ancient literature.[44] The surname of Alexander II has different spellings; it is "Zabinaeus" in the prologue of the Latin language Philippic Histories, book XXXIX. "Zebinas" was used by Josephus. The Greek rendition, Zabinas, was used by many historians such as Diodorus Siculus and Porphyry.[45] Zabinas is a Semitic proper name,[35] derived from the Aramaic verb זבן (pronounced Zabn), which means "buy" or "gain".[23][46] The meaning of Zabinas as a surname of Alexander II is "a slave sold in the market" according to philologist Pierre Jouguet.[47] This is based on a statement by Porphyry. He wrote that Alexander II was named Zabinas by the Syrians because he was a "bought slave".[27] In the view of archaeologist Jean-Antoine Letronne, who agreed that Alexander II was an imposter, a coin meant for the public could not have had "Zabinas" inscribed on it as it is derisory.[note 7][46] On the other hand, historian Philip Khuri Hitti noted that "Zebina", another rendering of Zabinas, occurs in Ezra (10:43), indicating it originally meant "bought from god".[48] The numismatist Nicholas L. Wright also considered that Zabinas meant "purchased from the god".[49]

Though academic consensus considers Alexander II an imposter of non-Seleucid birth,[50] Josephus accepted the king as a Seleucid dynast but did not specify his connection to earlier kings.[51] Historian Kay Ehling ascribed Josephus's acceptance to Alexander II's successful propaganda.[52] Wright, however, contends that Alexander II should be considered a legitimate Seleucid and a descendant of Antiochus IV using the following arguments:[53]

- Porphyry's account of the adoption by Antiochus VII might be based on facts.[51] Justin called Antiochus VI a step-son of Demetrius II.[54] In Wright's view, this association between Antiochus VI and his father's enemy might be an indication that Demetrius II adopted Antiochus VI in an attempt to close the rift in the royal family. Likewise, it is possible Alexander II was indeed a son of Alexander I adopted by Antiochus VII. The second century historian Arrian spoke of an Alexander, the son of Alexander I, who was elevated to kingship by Tryphon in 145 BC; this passage is puzzling as it is numismatically proven that it was Antiochus VI whom Tryphon raised to the throne. According to Wright, the language of Arrian indicates he probably had access to sources mentioning Alexander II as a son of Alexander I.[51]

- Justin's account regarding Protarchos, the alleged Egyptian father of Alexander II, is illogical.[35] Wright suggested Alexander II was an illegitimate son of Alexander I;[55] it is probable Alexander II might have been a younger son of Alexander I destined to become a priest, hence he was called Zabinas—purchased from the god.[35] It is dubious Alexander II was a low-born Egyptian man, whose claims to the throne were based on publicly known falsifications, yet he was accepted by the Syrians as their king.[53] The story about Alexander II's Egyptian origin was probably invented by the court of Demetrius II, maintained by the court of his son Antiochus VIII, and kept alive by ancient historians due to its scandalous nature.[35]

King of Syria

Ascending the throne

The young Antiochus Epiphanes likely died of an illness.[56] Alexander II, whose earliest coins from the capital are dated to 184 SE (129/128 BC), probably landed in northern Syria with Ptolemaic support and declared himself king, taking Antioch in the process;[23] the fall of the capital probably took place in spring 128 BC.[57] According to Justin's epitome, the Syrians were ready to accept any king other than Demetrius II.[36] Probably soon after capturing Antioch, Alexander II incorporated Laodicea ad mare and Tarsus into his domains.[note 8] Other cities, such as Apamea, had already freed themselves from Demetrius II during his Egyptian campaign and did not come immediately under Alexander II's authority.[57]

Epithets and royal image

Hellenistic kings did not use regnal numbers, which is a modern practice; instead, they used epithets to distinguish themselves from similarly named monarchs.[59][60] The majority of Alexander II's coins did not feature an epithet,[61] but the 125 BC series of gold staters bore the epithets Theos Epiphanes (god manifest) and Nikephoros (bearer of victory). Three bronze issues, one of them minted in Seleucia Pieria, are missing the epithet Theos but retain Epiphanes and Nikephoros.[62] Those epithets, an echo of those of Antiochus IV's, served to emphasise the legitimacy of Alexander II as a Seleucid king.[38]

Alexander the Great (d. 323 BC), founder of the Macedonian Empire, was an important figure in the Hellenistic world; his successors used his legacy to establish their legitimacy. Alexander the Great never had his image minted on his own coins,[63] but his successors, such as the Ptolemaics, sought to associate themselves with him; cities were named after him, and his image appeared on coins.[64] In contrast, the memory of Alexander the Great was not important for Seleucid royal ideology.[note 9][69][70] However, Alexander I and Alexander II, both having Egyptian support, were the only Seleucid kings who paid particular attention to Alexander the Great by depicting themselves wearing the lion scalp, a motif closely connected to the Macedonian king.[71] By associating himself with Alexander the Great, Alexander II was continuing the practice of Alexander I, who used the theme of Alexander the Great to strengthen his legitimacy.[note 10][73]

The native Syro-Phoenician religious complex was based on triads that included a supreme god, a supreme goddess, and their son; the deities taking those roles were diverse. It is possible that by 145 BC Dionysus took the role of the son.[74] The Levant was a multi-ethnic, multi-cultural region, but the religious complex was a unifying force. The Seleucid monarchs understood the possibility of using this complex to expand their support base amongst the locals by integrating themselves into the triads.[75] Usage of the radiate crown, a sign of divinity, by the Seleucid kings, probably carried a message: that the king was the consort of Atargatis, Syria's supreme goddess.[note 11][77] The radiate crown was utilised for the first time at an unknown date by Antiochus IV, who chose Hierapolis-Bambyce, the most important sanctuary of Atargatis, to ritually marry Diana, considered a manifestation of the Syrian goddess in the Levant.[78] Alexander I's nickname, Balas, was probably used by the king himself. It is the Greek rendering of Ba'al, the Levant's supreme god. By using such an epithet, Alexander I was declaring himself the embodiment of Ba'al. Alexander I also used the radiate crown to indicate his ritual marriage to the supreme goddess.[49] Alexander II made heavy use of the motifs of Dionysus in his coins.[42] It is possible that, by utilising Dionysus, the son of the supreme god, Alexander II presented himself as the spiritual successor of his god-father, in addition to being his political heir.[49]

Policy

One of Alexander II's first acts was the burial of Antiochus VII's remains which were returned by the Parthians. Burying the fallen king earned Alexander II the acclaim of Antioch's citizens;[note 12][36] it was probably a calculated move aiming at gaining the support of Antiochus VII's loyal men.[80] The seventh century chronicler John of Antioch wrote that following Antiochus VII's death, his son Seleucus ascended the throne and was quickly deposed by Demetrius II and fled to Parthia. Historian Auguste Bouché-Leclercq criticised this account, which is problematic and could be a version of Demetrius II's Parthian captivity corrupted by John of Antioch. However, it is possible that a son of Antiochus VII named Seleucus was captured by the Parthians along with his father and was later sent with Antiochus VII's remains to take the throne of Syria as a Parthian protégé. If this scenario happened, then Seleucus was faced by Alexander II and had to return to Parthia.[36]

Since he ascended the throne with Egyptian help, Alexander II was under Ptolemaic influence, which was manifested in the appearance of the Egyptian style double filleted cornucopiae on the Syrian coinage.[note 13][83] In Egypt, the double cornucopiae on coins might have been a reference to the union between the king and his consort.[84] If the appearance of cornucopiae on Alexander II's coinage was connected to Ptolemaic practices, then it can be understood that Alexander II might have married a Ptolemaic princess, though such a marriage is not recorded by ancient literature.[45]

According to Diodorus Siculus, Alexander II was "kindly and of a forgiving nature, and moreover was gentle in speech and in manners, wherefore he was deeply beloved by the common people".[85] Diodorus Siculus wrote that three of Alexander II's officers, Antipater, Klonios, and Aeropos, rebelled and entrenched themselves in Laodicea. Alexander II defeated the rebels and recaptured the city; he pardoned the culprits.[86] Bouché-Leclercq suggested that this rebellion took place in 128 BC and that the officers either defected to Demetrius II's side, were working for the son of Antiochus VII, or were instigated in their rebellion by Cleopatra Thea.[note 14][90]

War against Demetrius II

Between August 127 BC and August 126 BC, Ptolemy VIII regained Alexandria;[91] Cleopatra II fled to Demetrius II with the treasury of Egypt.[92] Despite Alexander II's success in taking the capital, Demetrius II retained Cilicia,[93] and Seleucia Pieria remained loyal to him, so did many cities in Coele-Syria; this led Alexander II to launch a campaign in the region.[94] The armies of the two kings passed through Judea causing a plight for the inhabitants. This led the Jews to send an embassy to Rome demanding "the prohibition of the marching of royal soldiers through the Jewish territory 'and that of their subjects'";[note 15][96] the embassy was between c. 127–125 BC.[97] By October 126 BC, Ashkelon fell into Alexander II's hands. Numismatic evidence indicates that Samaria came under Alexander II's control.[97] In the beginning of 125 BC, Demetrius II was defeated near Damascus and fled to Ptolemais.[94] Cleopatra Thea refused to allow her husband to stay in the city, so he headed to Tyre on board a ship.[98] Demetrius II asked for temple asylum in Tyre, but was killed by the city's commander (praefectus) in the spring or summer of 125 BC.[99]

Alexander II minted bronze coins depicting him with an elephant scalp headdress on the obverse,[94] and an aphlaston appears on the reverse; this can mean that Alexander II claimed a naval victory.[note 16][99] The sea battle between Alexander II and Demetrius II, which is not documented in ancient literature, may have occurred only during the voyage of Demetrius II from Ptolemais to Tyre.[99] The elephant scalp headdress was a theme in Alexander the Great's posthumous coinage minted by his successors.[note 17][63] According to Ehling, by appearing with the elephant scalp, Alexander II alluded to Alexander the Great's conquest of Tyre which took place in 332 BC after seven months of siege.[note 18][99] The 125 BC gold staters containing Alexander II's epithets were probably struck to celebrate his victory over Demetrius II.[note 19][62]

Relations with Judea

Under Antiochus VII, the Judean high-priest and ruler John Hyrcanus I acquired the status of a vassal prince, paying tribute and minting his coinage in the name of the Syrian monarch.[103] Following Antiochus VII's death, John Hyrcanus I ceased paying the tribute and minted coinage bearing his own name,[104] but ties were kept with the Seleucid kingdom through monograms, representing Seleucid kings, that appeared on the early coins.[105] The dating of this event is conjectural, with the earliest date possible 129 BC but more likely 128 BC.[106] Demetrius II apparently planned an invasion of Judea, which was halted due to the king's failed invasion of Egypt and the uprising that erupted in Syria.[107] According to Josephus, John Hyrcanus I "flourished greatly" under Alexander II's rule;[108] apparently, the Judean leader sought an alliance with Alexander II to defend himself against Demetrius II.[107]

The 127 BC embassy sent by Judea to Rome asked the senate to force the Syrian abandonment of: Jaffa, the Mediterranean harbours which included Iamnia and Gaza, the cities of Gazara and Pegae (near Kfar Saba), in addition to other territories taken by King Antiochus VII. A Roman senatus consultum (senatorial decree), preserved in Josephus's work Antiquities of the Jews (book XIV, 250), granted the Jews their request regarding the cities, but did not mention the city of Gazara.[109] The senatorial decree mentions the reigning Syrian king as Antiochus son of Antiochus, which can mean only Antiochus IX, who assumed the throne in 199 SE (114/113 BC).[110] The decree might indicate the Syrians had already abandoned Gazara in c. 187 SE (126/125 BC). This supports the notion that an agreement between Alexander II and John Hyrcanus I was signed early in the Syrian king's reign.[note 20] Such a treaty would have established the alliance between Alexander II and Judea, and stipulated a territorial agreement where John Hyrcanus I received the lands south of Gazara including that city, while Alexander II maintained control over the region north of Gazara including Samaria.[109]

John Hyrcanus I recognised Alexander II as his sovereign.[note 21][113] The earliest series of coins minted by the high priest showed the Greek letter Α (alpha) positioned prominently above John Hyrcanus I's name. The alpha must have been the first letter of a Seleucid king's name, and many scholars, such as Dan Barag, suggested that it represents Alexander II.[note 22][106] Another clue indicating the relationship between Alexander II and John Hyrcanus I is the latter's use of the double cornucopiae motif on his coins; a pomegranate motif appeared in the centre of the cornucopiae to highlight the authority of the Jewish leader.[108] This imagery was apparently a cautious policy by John Hyrcanus I. In case Alexander II was defeated, the Judean coins motifs were neutral enough to appease an eventual successor, while if Alexander II emerged victorious and decided to interfere in Judea, the cornucopiae coins could be used to show the king that John Hyrcanus I already accepted Alexander II's suzerainty.[116] The high priest eventually won the independence of Judea later in Alexander II's reign;[113] once John Hyrcanus I severed his ties with the Seleucids, the alpha was removed.[106]

Height of power and the break with Egypt

Following Demetrius II's death, Alexander II, commanding a force of forty thousand soldiers, brought Seleucia Pieria under his control.[117] Cilicia was also conquered in 125 BC along with other regions.[118] The coinage of Alexander II was minted in: Antioch, Seleucia Pieria, Apamea, Damascus, Beirut, Ashkelon and Tarsus, in addition to unknown minting centers in northern Syria, southern Coele-Syria and Cilicia (coded by numismatists: uncertain mint 111, 112, 113, 114).[119] In Ptolemais, Cleopatra Thea refused to recognise Alexander II as king; already in 187 SE (126/125 BC), the year of her husband's defeat, she struck tetradrachms in her own name as the sole monarch of Syria. Her son with Demetrius II, Seleucus V, declared himself king, but she had him assassinated. The people of Syria did not accept a woman as the sole monarch. This led Cleopatra Thea to choose her younger son by Demetrius II, Antiochus VIII, as a co-ruler in 186 SE (125/124 BC).[120]

According to Justin, Ptolemy VIII abandoned Alexander II after the death of Demetrius II and reconciled with Cleopatra II who went back to Egypt as a co-ruler.[121] Justin stated that Ptolemy VIII's reason for abandoning Alexander II was the latter's increased arrogance swelled by his successes that led him to treat his benefactor with insolence.[122] The change of Ptolemaic policy probably had less to do with Ptolemy VIII's pride than with Alexander II's victories; a strong neighbour in Syria was not a desired situation for Egypt.[123] It is also probable that Cleopatra Thea negotiated an alliance with her uncle.[124] Soon after Cleopatra II's return, Ptolemy VIII's daughter by Cleopatra III, Tryphaena, was married to Antiochus VIII. An Egyptian army was sent to support the faction of Antiochus VIII against Alexander II.[note 23][121] The return of Cleopatra II and the marriage of Antiochus VIII both took place in 124 BC.[127]

War with Antiochus VIII, defeat and death

Supported by the Egyptian troops, Antiochus VIII waged war against Alexander II, who lost most of his lands.[128] He lost Ashkelon in 189 SE (124/123 BC).[129] The final battle took place at an unknown location in the first half of 123 BC, ending with Alexander II's defeat.[128][125] Different ancient historians presented varying accounts of Alexander II's end. Josephus merely stated that the king was defeated and killed,[28] while Eusebius mentioned that Alexander II committed suicide with poison because he could not live with his defeat.[130] Most details are found in the accounts of Diodorus Siculus and Justin:[126]

- In the account of Diodorus Siculus, Alexander II decided to avoid the battle with Antiochus VIII since he had no confidence in his subjects'[131] aspirations for political change or their tolerance for the hardships that warfare would bring. Instead of fighting, Alexander II decided to take the royal treasuries, steal the valuables of the temples, and sail to Greece at night. While pillaging the temple of Zeus with some of his foreign subordinates, he was discovered by the populace and barely escaped with his life. Accompanied by a few men he went to Seleucia Pieria, but the news of his sacrilege arrived before him. The city closed its gates, forcing him to seek shelter in Posidium. Two days after pillaging the temple, Alexander II was caught and brought in chains to Antiochus VIII in his camp, suffering the insults and humiliation at the hands of his enemies. People who witnessed the indignation of Alexander II were shocked at the scene they thought could never happen. After accepting what had occurred in front of them was reality, they looked away with astonishment.[132]

- In the account of Justin, Alexander II fled to Antioch following his defeat at the hands of Antiochus VIII. Lacking the resources to pay his troops, the king ordered the removal of a golden Nike from the temple of Jupiter (Zeus), joking that "victory was lent to him by Jupiter". A few days later, Alexander II himself ordered the golden statue of Jupiter to be taken out under the cover of night. The city's populace revolted against the king, and he was forced to flee. He was later deserted by his men and caught by bandits; they delivered him to Antiochus VIII, who ordered him executed.[121]

Alexander II issued two series of gold staters. One bears his epithets and dates to 125 BC according to many numismatists, such as Oliver Hoover and Arthur Houghton, and another bearing only the title of king (basileus). Earlier numismatists, such as Edward Theodore Newell and Ernest Babelon, who only knew about the 125 BC stater, suggested that it was minted with the gold pillaged from the temple. However, the iconography of that stater does not match that used for Alexander II's late coinage, as the diadem ties fall in a straight fashion on the neck. On the other hand, the arrangement of the diadem ties on the stater that lacks the royal epithets is more consistent with Alexander II's late tetradrachm, making it more reasonable to associate that stater with the Nike theft.[note 24][62]

Though his last coins were issued in 190 SE (123/122 BC), ancient historians do not provide the explicit date of Alexander II's death.[133] He probably died by October 123 BC since the first Antiochene coins of Antiochus VIII were issued in 190 SE (123/122 BC).[134][126] Damascus kept striking coinage in the name of Alexander II until 191 SE (122/121 BC), when the forces of Antiochus VIII took it.[126] According to Diodorus Siculus, many who witnessed the king's end "remarked in various ways on the fickleness of fate, the reversals in human fortunes, the sudden turns of tide, and how changeable life could be, far beyond what anyone would expect".[135] No wife or children of Alexander II, if he had any, are known;[27] with his death, the line of Antiochus IV became extinct.[53]

See also

Notes

- ^ According to the 188 BC Treaty of Apamea, King Antiochus III, who lost a war against Rome, agreed to send his son Antiochus IV as a hostage. After Antiochus III's death in 187 BC, his eldest son Seleucus IV replaced Antiochus IV with his own son Demetrius I, as the son of the ruling king was considered a better guarantee of loyalty by Rome. The exchange took place before 178 BC.[1]

- ^ Some dates in the article are given according to the Seleucid era which is indicated when two years have a slash separating them. Each Seleucid year started in the late autumn of a Gregorian year; thus, a Seleucid year overlaps two Gregorian ones.[3]

- ^ Cleopatra III was not mentioned as a queen or a wife of Ptolemy VIII in a document dated to 8 May 141 BC. The first attestation of Cleopatra III as wife of Ptolemy VIII dates to 14 January 140 BC (P. dem. Amherst 51), thus, the marriage took place between May 141 BC and January 140 BC. The word for queen, "Pr-ʿȜ.t", is hard to read in P. dem. Amherst 51 as only traces of ink remain; the Egyptologist Pieter Pestman expressed his doubts of its existence,[15] while the Egyptologist Giuseppina Lenzo, after inspecting the original document, considered the title's presence plausible.[16]

- ^ The original Philippic Histories of Trogus consisted of forty four books and is lost.[24] Justin produced a three hundred page epitome of Trogus's forty four books, which was in reality an extract of the original work.[25] It does not seem that Justin added his own material to the epitome, but his book was not an accurate reproduction of the original work.[26] Justin's epitome, a summarised version of the original work and full of omissions, eclipsed Trogus's in popularity and resulted in the latter's disappearance.[24]

- ^ Fragments of Trogus's original history survive in the works of several ancient historians. The Prologues of Trogus are summaries of each of the forty-four books, whose author and date are unknown, that reached the modern era appended to some of the manuscripts containing Justin's epitome of Trogus's original work.[29] It is possible the prologues preserve some of Trogus's original wording.[30]

- ^ Historian Kay Ehling proposed, based on the king's portrait known from his coins, that Alexander II was no more than twenty years old when his reign began in 128 BC. If he was a son of Alexander I, who died in 145 BC, then he could not have been younger than sixteen years old when he ascended the throne.[32]

- ^ Hubertus Goltzius forged a medal of Alexander II carrying the surname "Zebinas" based on the work of Josephus; this medal was unanimously rejected by numismatists.[46]

- ^ Ehling suggested that Tarsus came under Alexander II's rule early in his reign.[57] Others, such as the numismatists Arthur Houghton and Oliver Hoover, maintained that the city produced enough coins in the name of Demetrius II to make it plausible that he retained it throughout his reign which ended in 125 BC.[58]

- ^ The image of Alexander the Great appeared on the coinage of the first Seleucid king Seleucus I, who used his predecessor's memory to legitimise his rule.[65] On the other hand, Seleucus I's successors, starting with his son Antiochus I, dropped Alexander the Great's image from their coinage, and derived their legitimacy from the deified Seleucus I.[66] However, the "Alexander portrait type", based on the image of Alexander created by his immediate successors, was the base for the royal portrait type used by the Seleucid monarchs. The "Alexander portrait type" is characterised by the upward gaze of the king, and an anastolic hair (a cut where the hair arises off-centre from the forehead, allowing it to fall over it, forming a fringe, and the remaining hair falling on the shoulders, forming a mane or crown).[67][68]

- ^ Alexander I, in contrast to all previous kings, was probably born out of wedlock to Antiochus IV and a concubine, and he was called a bastard by the second century historian, Appian.[7] Since Antiochus IV was a deified king, Alexander I used the epithet theopator (son of the god), which emphasised his divine descent and paid no attention to his mother whose status was insignificant for a god's son. By using the iconography of Alexander the Great, Alexander I was alluding to the fact that a son of a deity does not need conventional legitimacy, since Alexander the Great was said to be the son of Zeus-Amon instead of his actual father, Philip II.[72]

- ^ Wright proposed the hypothesis regarding the connection between the Seleucid radiate crowns and Atargatis. He considered it likely, but difficult to prove, that a radiate crown indicates a ritual marriage between the goddess and a king.[76]

- ^ This episode might explain the account of Justin regarding the adoption of Alexander II by Antiochus VII.[36] The historian Thomas Fischer argued that Seleucus, son of Antiochus VII, actually succeeded his father in Antioch following the failed Parthian campaign, then he escaped to Parthia when Demetrius II reached the capital.[79]

- ^ The earliest appearance of cornucopiae in Near Eastern coinage was in Ptolemaic Egypt.[81] Ptolemy II minted coins depicting filleted cornucopiae to commemorate his sister and queen, Arsinoe II, following her death in c. 268 BC.[45] Demetrius I was the first Syrian king to introduce the cornucopia motif in Syrian coinage, but Alexander II was the first Syrian king to use the motif in an Egyptian style. He also introduced his own style depicting symmetrical cornucopiae with intertwined ends.[82]

- ^ The Laodicea meant is most likely Laodicea ad mare, a notion supported by several historians such as Bouché-Leclercq, Getzel M. Cohen and John D Grainger.[87] The historian Edwyn Bevan suggested Laodicea in Phoenicia (modern Beirut), and that the rebellion took place after Demetrius II's death.[88] The historian Adolf Kuhn connected this episode to the fight between Alexander II and Demetrius II's son, Antiochus VIII, thus dating it to 123 BC.[89] Bouché-Leclercq considered Kuhn's suggestion possible, but rejected Bevan's hypothesis.[90]

- ^ The Jewish delegation was led by Simon son of Dositheus, Apollonius son of Alexander and Diodorus son of Jason.[95]

- ^ The inscription of Antigonus son of Menophilus, a Seleucid admiral (nauarchos), was discovered in the city of Miletus. Antigonus described himself as the "admiral of Alexander, king of Syria"; Alexander II could be the king mentioned.[100] The archaeologist Peter Herrmann considered it possible that Alexander II was the king in question, but maintained that a better candidate would be Alexander I, who was known for his relations with Miletus.[101]

- ^ In Ptolemaic Egypt, Alexander the Great was shown wearing an elephant scalp, a motif not used by the Macedonian king himself. It first appeared on posthumous coins issued by Ptolemy I.[102]

- ^ In the view of Hoover, although Alexander II appeared wearing the elephant scalp, Alexander the Great was probably not alluded to. According to Hoover, in a Seleucid context, a king's utilisation of the elephant scalp probably indicated a victory in the East.[69] This view is contested by many scholars, such as Wright, who maintained that Alexander II's usage of the elephant scalp motif was connected to Alexander the Great.[35]

- ^ Alexander II's gold staters did not have any magistrate marks, indicating that they were a special issue and not part of the regular production. Therefore, the gold staters must have been issued under special circumstances.[62]

- ^ Kuhn asserted that the alliance was sealed only after the death of Demetrius II and before the ascension of his successor Antiochus VIII.[111]

- ^ John Hyrcanus I was virtually independent and his gestures towards Alexander II were just a facade.[112]

- ^ French numismatist Louis Félicien de Saulcy suggested in 1854 that the alpha represented the initial letter of the name of either Antiochus VII or Alexander II. Numismatists Dan Barag and Shraga Qedar suggested Alexander II or Antiochus VIII instead.[106] Historian Baruch Kanael considered it implausible that the alpha designated a king, since no Seleucid king is known to have settled for the appearance of his initials instead of his full name on the coins of vassal states.[114] Some scholars attribute the alpha series coins to John Hyrcanus II, and many interpretations were offered to explain the letter.[115] For example, the numismatist Arie Kindler suggested that it might represent Salome Alexandra, mother of John Hyrcanus II, or, in the view of the numismatist Ya'akov Meshorer, might be a reference for Antipater the Idumaean, John Hyrcanus II's advisor and the power behind the throne.[105]

- ^ The treaty between Cleopatra Thea and Ptolemy VIII is not mentioned in ancient sources, but several historians, such as Alfred Bellinger and John Whitehorne, consider its existence likely.[125][124] The installation of Antiochus VIII on his throne might also have been part of the deal; given the fact that Cleopatra Thea killed her eldest son to remain a sole monarch, her acceptance of sharing her power with Antiochus VIII can be understood if it was part of a deal she struck under the pressure of Alexander II's victories.[126]

According to Bouché-Leclercq, it was Cleopatra II who probably pushed for Egypt's abandonment of Alexander II, and the establishment of the alliance between Ptolemy VIII and Antiochus VIII, which included the dynastic marriage of the Syrian king and Tryphaena.[122] - ^ The association of the gold stater with the sacrilege act can be accepted only if the account of Justin is preferred to that of Diodorus Siculus, as he stated that Alexander II was caught only two days after pillaging the temple, giving the king no time to mint currency.[62]

References

Citations

- ^ Allen 2019, p. 137.

- ^ Sartre 2009, p. 243.

- ^ Biers 1992, p. 13.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 78.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 127.

- ^ Kosmin 2014, p. 133.

- ^ a b Wright 2011, p. 43.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 209.

- ^ a b Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 261.

- ^ Lenzo 2015, pp. 226, 227.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 315.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 262.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 263.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, pp. 349, 350.

- ^ Pestman 1993, p. 86.

- ^ Lenzo 2015, p. 228.

- ^ Whitehorne 2002, p. 206.

- ^ Mørkholm 1975, p. 11.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 350.

- ^ a b Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 409.

- ^ Mitford 1959, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Hoover & Iossif 2009, p. 48.

- ^ a b c Chrubasik 2016, p. 143.

- ^ a b Justin 1997, p. 1.

- ^ Winterbottom 2006, p. 463.

- ^ Anson 2015, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Ogden 1999, p. 152.

- ^ a b Josephus 1833, p. 413.

- ^ Justin 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Yardley 2003, p. 92.

- ^ Justin 1994, p. 284.

- ^ Ehling 2008, p. 208.

- ^ Grainger 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Romm 2005, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f Wright 2011, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d e f Shayegan 2003, p. 96.

- ^ a b Ehling 1995, p. 2.

- ^ a b Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 444.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 442.

- ^ a b Mørkholm 1983, p. 62.

- ^ Ehling 1995, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Ehling 1995, p. 5.

- ^ Ehling 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Ehling 2008, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Jacobson 2013a, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Letronne 1842, p. 63.

- ^ Jouguet 1928, p. 380.

- ^ Hitti 1951, p. 256.

- ^ a b c Wright 2005, p. 81.

- ^ Wright 2008, p. 536.

- ^ a b c Wright 2008, p. 537.

- ^ Ehling 2008, p. 209.

- ^ a b c Wright 2008, p. 538.

- ^ Justin, Cornelius Nepos & Eutropius 1853, p. 244.

- ^ Wright 2012, p. 10.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 436.

- ^ a b c Ehling 1998, p. 145.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 447.

- ^ McGing 2010, p. 247.

- ^ Hallo 1996, p. 142.

- ^ Fleischer 1991, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d e Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 449.

- ^ a b Rice 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Wallace 2018, p. 164.

- ^ Erickson 2013, pp. 110, 112.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 71.

- ^ Plantzos 1999, p. 54.

- ^ Smith 2001, p. 196.

- ^ a b Hoover 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Dahmen 2007, p. 15.

- ^ Hoover 2002, pp. 54, 56.

- ^ Wright 2011, p. 44.

- ^ Wright 2011, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 77, 78.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Wright 2005, p. 79.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 79, 80.

- ^ Wright 2005, pp. 74, 78.

- ^ Colledge 1972, p. 426.

- ^ Chrubasik 2016, p. 171.

- ^ Eyal 2013, p. 203.

- ^ Barag & Qedar 1980, p. 16.

- ^ Jacobson 2013a, p. 50.

- ^ Fulińska 2010, p. 82.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus 1984, p. 111.

- ^ Cohen 2006, p. 112.

- ^ Cohen 2006, p. 114.

- ^ Bevan 1902, p. 251.

- ^ Kuhn 1891, p. 17.

- ^ a b Bouché-Leclercq 1913, p. 393.

- ^ Mitford 1959, pp. 103, 104.

- ^ Green 1990, p. 540.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 441.

- ^ a b c Ehling 1998, p. 146.

- ^ Shatzman 2012, p. 61.

- ^ Shatzman 2012, pp. 62, 64.

- ^ a b Finkielsztejn 1998, p. 45.

- ^ Ehling 1996, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d Ehling 1998, p. 147.

- ^ Kosmin 2014, p. 112.

- ^ Herrmann 1987, p. 185.

- ^ Maritz 2016, p. 41.

- ^ Hoover 1994, p. 43.

- ^ Hoover 1994, p. 47.

- ^ a b Hendin 2013, p. 265.

- ^ a b c d Barag & Qedar 1980, p. 18.

- ^ a b Shatzman 2012, p. 51.

- ^ a b Hoover 1994, p. 50.

- ^ a b Finkielsztejn 1998, p. 46.

- ^ Seeman 2013, p. 196.

- ^ Kuhn 1891, p. 16.

- ^ Ehling 1998, p. 51.

- ^ a b Jacobson 2013b, p. 21.

- ^ Kanael 1952, p. 191.

- ^ Brug 1981, p. 109.

- ^ Hoover 1994, p. 51.

- ^ Ehling 1998, p. 148.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, pp. 441, 442.

- ^ Houghton, Lorber & Hoover 2008, p. 445.

- ^ Ehling 1998, pp. 148, 149.

- ^ a b c Justin 1742, p. 279.

- ^ a b Bouché-Leclercq 1913, p. 398.

- ^ Chrubasik 2016, p. 172.

- ^ a b Whitehorne 2002, p. 161.

- ^ a b Bellinger 1949, p. 64.

- ^ a b c d Bellinger 1949, p. 65.

- ^ Otto & Bengtson 1938, pp. 103, 104.

- ^ a b Ehling 1998, p. 149.

- ^ Spaer 1984, p. 230.

- ^ Eusebius 1875, p. 257.

- ^ Stronk 2016, p. 521.

- ^ Stronk 2016, p. 522.

- ^ Schürer 1973, p. 132.

- ^ Ehling 1998, p. 150.

- ^ Stronk 2016, p. 523.

Sources

- Allen, Joel (2019). The Roman Republic in the Hellenistic Mediterranean: From Alexander to Caesar. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-95933-6.

- Anson, Edward M. (2015). Eumenes of Cardia: A Greek among Macedonians. Mnemosyne, Supplements, History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity. Vol. 383 (second ed.). Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-29717-3. ISSN 2352-8656.

- Barag, Dan; Qedar, Shraga (1980). "The Beginning of Hasmonean Coinage". Israel Numismatic Journal. 4. Israel Numismatic Society. ISSN 0021-2288.

- Bellinger, Alfred R. (1949). "The End of the Seleucids". Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 38. Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. OCLC 4520682.

- Bevan, Edwyn Robert (1902). The House of Seleucus. Vol. II. Edward Arnold. OCLC 499314408.

- Biers, William R. (1992). Art, Artefacts and Chronology in Classical Archaeology. Approaching the Ancient World. Vol. 2. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-06319-7.

- Bouché-Leclercq, Auguste (1913). Histoire des Séleucides (323–64 avant J.-C.) (in French). Ernest Leroux. OCLC 558064110.

- Brug, John F. (1981). "An Interdisciplinary Study of the "A" Coins of Yehochanan". The Augur: Journal of the Biblical Numismatic Society. 31/32. Biblical Numismatic Society. Archived from the original on 4 June 2020. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- Chrubasik, Boris (2016). Kings and Usurpers in the Seleukid Empire: The Men who Would be King. Oxford Classical Monographs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-78692-4.

- Cohen, Getzel M. (2006). The Hellenistic Settlements in Syria, the Red Sea Basin, and North Africa. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 46. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-93102-2.

- Colledge, Malcolm A. R. (1972). "Thomas Fischer: Untersuchungen zum Partherkrieg Antiochos' VII. im Rahmen der Seleukidengeschichte. (München Diss.) Pp. ix + 125: 1 Map. Tübingen: Privately Printed, 1970 (Obtainable from the Author, Heinleinstrasse 28, 74 Tübingen-Derendingen.) Paper, DM.12". The Classical Review. 22 (3). Cambridge University Press for the Classical Association: 426–427. doi:10.1017/S0009840X00997439. ISSN 0009-840X. S2CID 163004316.

- Dahmen, Karsten (2007). The Legend of Alexander the Great on Greek and Roman Coins. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-15971-0.

- Diodorus Siculus (1984) [c. 20 BC]. Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Vol. 423. Translated by Walton, Francis R. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-434-99423-6.

- Ehling, Kay (1995). "Alexander II Zabinas – Ein Angeblicher (Adoptiv-)Sohn Des Antiochos VII. Oder Alexander I. Balas?". Schweizer Münzblätter (in German). 45 (177). Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Numismatik. ISSN 0016-5565.

- Ehling, Kay (1996). "Zu einer Bronzemünze des Alexander II. Zabinas". Schweizer Münzblätter (in German). 46 (183). Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Numismatik. ISSN 0016-5565.

- Ehling, Kay (1998). "Seleukidische Geschichte zwischen 130 und 121 v.Chr". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte (in German). 47 (2). Franz Steiner Verlag: 141–151. ISSN 0018-2311. JSTOR 4436499.

- Ehling, Kay (2008). Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der späten Seleukiden (164-63 v. Chr.) vom Tode Antiochos IV. bis zur Einrichtung der Provinz Syria unter Pompeius. Historia – Einzelschriften (in German). Vol. 196. Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-09035-3. ISSN 0071-7665.

- Erickson, Kyle (2013). "Seleucus I, Zeus and Alexander". In Mitchell, Lynette; Melville, Charles (eds.). Every Inch a King: Comparative Studies on Kings and Kingship in the Ancient and Medieval Worlds. Rulers & Elites. Vol. 2. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-22897-9. ISSN 2211-4610.

- Eusebius (1875) [c. 325]. Schoene, Alfred (ed.). Eusebii Chronicorum Libri Duo (in Latin). Vol. 1. Translated by Petermann, Julius Heinrich. Apud Weidmannos. OCLC 312568526.

- Eyal, Regev (2013). The Hasmoneans: Ideology, Archaeology, Identity. Journal of Ancient Judaism. Supplements. Vol. 10. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-55043-4. ISSN 2198-1361.

- Finkielsztejn, Gerald (1998). "More Evidence on John Hyrcanus I's Conquests: Lead Weights and Rhodian Amphora Stamps". Strata: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. 16. The Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. ISSN 0266-2442.

- Fleischer, Robert (1991). Studien zur Seleukidischen Kunst (in German). Vol. I: Herrscherbildnisse. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-805-31221-9.

- Fulińska, Agnieszka (2010). "Iconography of the Ptolemaic Queens on Coins: Greek Style, Egyptian Ideas?". Studies in Ancient Art and Civilization. 14. Jagiellonian University Institute of Archaeology. ISSN 1899-1548.

- Grainger, John D. (1997). A Seleukid Prosopography and Gazetteer. Mnemosyne, Bibliotheca Classica Batava. Supplementum. Vol. 172. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-10799-1. ISSN 0169-8958.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Hellenistic Culture and Society. Vol. 1. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08349-3. ISSN 1054-0857.

- Hallo, William W. (1996). Origins. The Ancient Near Eastern Background of Some Modern Western Institutions. Studies in the History and Culture of the Ancient Near East. Vol. 6. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10328-3. ISSN 0169-9024.

- Hendin, David (2013). "Current Viewpoints on Ancient Jewish Coinage: A Bibliographic Essay". Currents in Biblical Research. 11 (2). SAGE Publishing: 246–301. doi:10.1177/1476993X12459634. ISSN 1476-993X. S2CID 161300543.

- Herrmann, Peter (1987). "Milesier am Seleukidenhof. Prosopographische Beiträge zur Geschichte Milets im 2. Jhdt. v. Chr". Chiron: Mitteilungen der Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts (in German). 17. Verlag C.H.Beck. ISSN 0069-3715.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1951). History of Syria: including Lebanon and Palestine. Macmillan. OCLC 5510718.

- Hoover, Oliver (1994). "Striking a Pose: Seleucid Types and Machtpolitik on the Coins of John Hyrcanus I". The Picus. 3. Classical & Medieval Numismatic Society. ISSN 1188-519X.

- Hoover, Oliver (2002). "The Identity of the Helmeted Head on the 'Victory' Coinage of Susa". Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau. 81. Schweizerischen Numismatischen Gesellschaft. ISSN 0035-4163.

- Hoover, Oliver D.; Iossif, Panagiotis (2009). "A Lead Tetradrachm of Tyre from the Second Reign of Demetrius II". The Numismatic Chronicle. 169. Royal Numismatic Society. ISSN 0078-2696.

- Houghton, Arthur; Lorber, Catherine; Hoover, Oliver D. (2008). Seleucid Coins, A Comprehensive Guide: Part 2, Seleucus IV through Antiochus XIII. Vol. 1. The American Numismatic Society. ISBN 978-0-980-23872-3. OCLC 920225687.

- Jacobson, David M. (2013a). "Military Symbols on the Coins of John Hyrcanus I". Strata: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. 31. The Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. ISSN 0266-2442.

- Jacobson, David M. (2013b). "The Lily and the Rose: A Review of Some Hasmonean Coin Types". Near Eastern Archaeology. 76 (1). The American Schools of Oriental Research: 16–27. doi:10.5615/neareastarch.76.1.0016. ISSN 2325-5404. S2CID 163858022.

- Josephus (1833) [c. 94]. Burder, Samuel (ed.). The Genuine Works of Flavius Josephus, the Jewish Historian. Translated by Whiston, William. Kimber & Sharpless. OCLC 970897884.

- Jouguet, Pierre (1928). Macedonian Imperialism and the Hellenization of the East. The History of Civilization. Translated by Dobie, Marryat Ross. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd. OCLC 834204719.

- Justin (1742) [c. 200 AD]. Justin's History of the World. Translated into English. With a Prefatory Discourse, Concerning the Advantages Masters Ought Chiefly to Have in Their View, in Reading and Ancient Historian, Justin in Particular, with their Scholars. By a Gentleman of the University of Oxford. Translated by Turnbull, George. T. Harris. OCLC 27943964.

- Justin; Cornelius Nepos; Eutropius (1853) [c. 200 AD (Justin), c. 25 BC (Nepos), c. 390 AD (Eutropius)]. Justin, Cornelius Nepos, and Eutropius, Literally Translated, with Notes and a General Index. Bohn's Classical Library. Vol. 44. Translated by Watson, John Selby. Henry G. Bohn. OCLC 20906149.

- Justin (1994) [c. 200 AD]. Develin, Robert (ed.). Justin: Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus. With Introduction and Explanatory Notes. American Philological Association Classical Resources Series. Vol. 3. Translated by Yardley, John C. Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1-555-40950-0.

- Justin (1997) [c. 200 AD]. Heckel, Waldemar (ed.). Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus. Clarendon Ancient History Series. Vol. I. Books 11-12, Alexander the Great. Translated by Yardley, John C. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-198-14907-1.

- Kanael, Baruch (1952). "The Greek Letters and Monograms on the Coins of Jehohanan the High Priest". Israel Exploration Journal. 2 (3). Israel Exploration Society: 190–194. ISSN 0021-2059. JSTOR 27924485.

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- Kuhn, Adolf (1891). Beiträge zur Geschichte der Seleukiden vom Tode Antiochos VII. Sidetes bis auf Antiochos XIII. Asiatikos 129–64 V. C (in German). Altkirch i E. Buchdruckerei E. Masson. OCLC 890979237.

- Lenzo, Giuseppina (2015). "A Xoite Stela of Ptolemy VIII Euergetes II with Cleopatra II and Cleopatra III (British Museum EA 612)". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 101 (1). Sage Publishing in Association with Egypt Exploration Society: 217–237. doi:10.1177/030751331510100111. ISSN 0307-5133. S2CID 193697314.

- Letronne, Jean-Antoine (1842). Recueil des inscriptions grecques et latines de l'Égypte (in French). Vol. Deuxième. L'Imprimerie Royal. OCLC 83866272.

- Maritz, Jessie (2016) [2004]. "The Face of Alexandria – the Face of Africa?". In Hirst, Anthony; Silk, Michael (eds.). Alexandria, Real and Imagined. Publications of the Centre for Hellenic Studies, King's College London. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-95959-9.

- McGing, Brian C. (2010). Polybius' Histories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-71867-2.

- Mitford, Terence Bruce (1959). "Helenos, Governor of Cyprus". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 79. The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies: 94–131. doi:10.2307/627925. ISSN 0075-4269. JSTOR 627925. S2CID 163636693.

- Mørkholm, Otto (1975). "Ptolemaic Coins and Chronology: The Dated Silver Coinage of Alexandria". Museum Notes. 20. The American Numismatic Society. ISSN 0145-1413.

- Mørkholm, Otto (1983). "A Posthumous Issue of Antiochus IV of Syria". The Numismatic Chronicle. 143. Royal Numismatic Society: 62. ISSN 0078-2696. JSTOR 42665167.

- Ogden, Daniel (1999). Polygamy, Prostitutes and Death: The Hellenistic Dynasties. Duckworth with the Classical Press of Wales. ISBN 978-0-715-62930-7.

- Otto, Walter Gustav Albrecht; Bengtson, Hermann (1938). Zur Geschichte des Niederganges des Ptolemäerreiches: ein Beitrag zur Regierungszeit des 8. und des 9. Ptolemäers. Abhandlungen (Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Philosophisch-Historische Klasse) (in German). Vol. 17. Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. OCLC 470076298.

- Pestman, Pieter Willem (1993). The Archive of the Theban Choachytes (second Century B.C.): A Survey of the Demotic and Greek Papyri Contained in the Archive. Studia Demotica. Vol. 2. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-9-068-31489-2. ISSN 1781-8575.

- Plantzos, Dimitris (1999). Hellenistic Engraved Gems. Oxford Monographs on Classical Archaeology. Vol. 16. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-198-15037-4.

- Rice, Ellen E (2010) [2006]. "Alexander III the Great 356-323 BC". In Wilson, Nigel (ed.). Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-78800-0.

- Romm, James, ed. (2005). Alexander The Great: Selections from Arrian, Diodorus, Plutarch, and Quintus Curtius. Translated by Romm, James; Mensch, Pamela. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-1-603-84062-0.

- Sartre, Maurice (2009) [2006]. Histoires Grecques: Snapshots from Antiquity. Revealing Antiquity. Vol. 17. Translated by Porter, Catherine. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-03212-5.

- Schürer, Emil (1973) [1874]. Vermes, Geza; Millar, Fergus; Black, Matthew (eds.). The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ. Vol. I (2014 ed.). Bloomsbury T&T Clark. ISBN 978-1-472-55827-5.

- Seeman, Chris (2013). Rome and Judea in Transition: Hasmonean Relations with the Roman Republic and the Evolution of the High Priesthood. American University Studies: Theology and Religion. Vol. 325. Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 978-1-433-12103-6. ISSN 0740-0446.

- Shatzman, Israel (2012). "The Expansionist Policy of John Hyrcanus and his Relations with Rome". In Urso, Gianpaolo (ed.). Iudaea Socia, Iudaea Capta: Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Cividale del Friuli, 22–24 Settembre 2011. I Convegni Della Fondazione Niccolò Canussio. Vol. 11. Edizioni ETS. ISBN 978-8-846-73390-0. ISSN 2036-9387.

- Shayegan, M. Rahim (2003). "On Demetrius II Nicator's Arsacid Captivity and Second Rule". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. New. 17. Asia Institute: 83–103. ISSN 0890-4464. JSTOR 24049307.

- Smith, Roland Ralph Redfern (2001) [1993]. "The Hellenistic Period". In Boardman, John (ed.). The Oxford History of Classical Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-14386-4.

- Spaer, Arnold (1984). "Ascalon: from Royal Mint to Autonomy". In Houghton, Arthur; Hurter, Silvia; Mottahedeh, Patricia Erhart; Scott, Jane Ayer (eds.). Festschrift für Leo Mildenberg : Numismatik, Kunstgeschichte, Archäologie. Editions NR. ISBN 978-9-071-16501-6.

- Stronk, Jan (2016). Semiramis' Legacy: The History of Persia According to Diodorus of Sicily. Edinburgh Studies in Ancient Persia. Vol. 3. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-474-41426-5.

- Wallace, Shane (2018). "Metalexandron: Receptions of Alexander in the Hellenistic and Roman Worlds". In Moore, Kenneth Royce (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Alexander the Great. Brill's Companions to Classical Reception. Vol. 14. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-35993-2.

- Whitehorne, John (2002) [1994]. Cleopatras. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-05806-3.

- Winterbottom, Michael (2006). "J. C. Yardley, Justin and Pompeius Trogus: A Study of the Language of Justin's Epitome of Trogus, Phoenix: Supplementary Volume XLI (Toronto, Buffalo and London: University of Toronto Press, 2003), XVII + 284 pp". International Journal of the Classical Tradition. 12 (3). Springer. ISSN 1073-0508. JSTOR 30222069.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2005). "Seleucid Royal Cult, Indigenous Religious Traditions and Radiate Crowns: The Numismatic Evidence". Mediterranean Archaeology. 18. Sydney University Press: 81. ISSN 1030-8482.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2008). "From Zeus to Apollo and Back Again: a Note on the Changing Face of Western Seleucid Coinage". Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia. 39–40 (part 2). Oriental Society of Australia: 537–538. ISSN 0030-5340.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2011). "The Iconography of Succession Under the Late Seleukids". In Wright, Nicholas L. (ed.). Coins from Asia Minor and the East: Selections from the Colin E. Pitchfork Collection. The Numismatic Association of Australia. ISBN 978-0-646-55051-0.

- Wright, Nicholas L. (2012). Divine Kings and Sacred Spaces: Power and Religion in Hellenistic Syria (301–64 BC). British Archaeological Reports (BAR) International Series. Vol. 2450. Archaeopress. ISBN 978-1-407-31054-1.

- Yardley, John C. (2003). Justin and Pompeius Trogus: A Study of the Language of Justin's Epitome of Trogus. Vol. 41. Supplementary Volume. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-802-08766-9. ISSN 0079-1784.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help)

External links

- The biography of Alexander II in the website of the numismatist Petr Veselý.