Albert Pinkham Ryder

Albert Pinkham Ryder | |

|---|---|

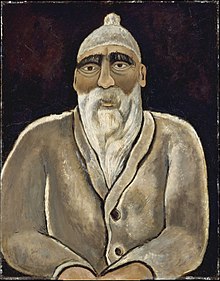

Ryder in 1905, photo by Alice Boughton | |

| Born | March 19, 1847 |

| Died | March 28, 1917 (aged 70) New York City, US |

| Education | National Academy of Design |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Tonalism |

Albert Pinkham Ryder (March 19, 1847 – March 28, 1917) was an American painter best known for his poetic and moody allegorical works and seascapes, as well as his eccentric personality. While his art shared an emphasis on subtle variations of color with tonalist works of the time, it was unique for accentuating form in a way that some art historians regard as a precursor to modernism.

Early life

Ryder was born in New Bedford, Massachusetts.[1] New Bedford, a bustling whaling port during the 19th century, had an intimate connection with the sea that probably supplied artistic inspiration for Ryder later in life. He was the youngest of four sons; little else is known of his childhood. He began to paint landscapes while in New Bedford.[1] The Ryder family moved to New York City in 1867 or 1868 to join Ryder's elder brother, who had opened a successful restaurant. His brother also managed the Hotel Albert, which became a Greenwich Village landmark. Ryder took his meals at this hostelry for many years, but it was named for the original owner, Albert Rosenbaum, not the painter.[2] Ryder applied to the National Academy of Design but his application got rejected.[3]

Training and early career

The early view of Ryder was that he was a recluse, holding that he developed his style in isolation and without influence from contemporary American or European art, but this view has been contradicted by later scholarship that has revealed his many associations and exposures to other artists.[1] Ryder's first training in art was with the painter William Edgar Marshall in New York.[1] From 1870 to 1873, and again from 1874 to 1875, Ryder studied art at the National Academy of Design.[1] He exhibited his first painting there in 1873 and met artist J. Alden Weir, who became his lifelong friend. In 1877, Ryder made the first of four trips to Europe throughout his life, where his studying of the paintings of the French Barbizon school and the Dutch Hague School would have a significant impact on his work.[1] Also in 1877, he became a founding member of the Society of American Artists.[1] The Society was a loosely organized group whose work did not conform to the academic standards of the day, and its members included Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Robert Swain Gifford (also from New Bedford), Ryder's friend Julian Alden Weir, John LaFarge, and Alexander Helwig Wyant. Ryder exhibited with this group from 1878 to 1887. His early paintings of the 1870s were often tonalist landscapes, sometimes including cattle, trees and small buildings.

- The Spirit of Autumn (c. 1875) Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, Ohio.

- The Grazing Horse (1872 to 1878) oil on canvas, 10 x 14 in. Brooklyn Museum

- Children Frightened by a Rabbit (1870s) oil on leather, 38.5 x 20.25 in. Smithsonian

- Summers Fruitful Pastures (mid 1870s) oil on wood, 7.75 x 10 in. Brooklyn Museum

- The Lone Scout, c. 1885) oil on canvas, 2.9 x 10 in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- In the Stable (early to mid 1870s) oil on canvas, 21 x32 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum

Artistic maturity

The 1880s and 1890s are thought of as Ryder's most creative and artistically mature period. During the 1880s, Ryder exhibited frequently and his work was well received by critics.[1] His art became more poetic and imaginative, and Ryder wrote poetry to accompany many of his works. His paintings sometimes depicted scenes from literature, opera, and religion. Ryder's signature style is characterized by broad, sometimes ill-defined shapes or stylized figures situated in a dream-like land or seascape. His scenes are often illuminated by dim sunlight or glowing moonlight cast through eerie clouds. The shift in Ryder's art from pastoral landscapes to more mystical, enigmatic subjects is believed to have been influenced by Robert Loftin Newman, with whom Ryder shared a studio.[1]

- Jonah. (mid 1880s to 1890s). oil on canvas, 27.25 x 34.37 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

- Constance (mid 1880s to mid 1890s) oil on canvas. 28.25 x 36 in. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- The Flying Dutchman, c. 1896, oil on canvas mounted on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

- Siegfried and the Rhine Maidens (1888–1891), oil on canvas, 20 x 20.50 in. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

- The Race Track (Death on a Pale Horse) (1895–1910), oil on canvas, 28.25 x 35.25. Cleveland Museum of Art

Later years

After 1900, around the time of his father's death, Ryder's creativity fell dramatically. For the rest of his life he spent his artistic energy on occasionally re-working existing paintings, some of which lay scattered about his New York apartment. Visitors to Ryder's home were struck by his slovenly habits—he never cleaned, and his floor was covered with trash, plates with old food, and a thick layer of dust, and he would have to clear space for visitors to stand or sit. He was shy and did not seek the company of others, but received company courteously and enjoyed telling stories or talking about his art. He gained a reputation as a loner, but he maintained social contacts, enjoyed writing letters, and continued to travel on occasion to visit friends.

While Ryder's creativity fell after the turn of the century, his fame grew. Important collectors of American art sought Ryder paintings for their holdings and often lent choice examples for national art exhibitions, as Ryder himself had lost interest in actively exhibiting his work. In 1913, ten of his paintings were shown together in the historic Armory Show, an honor reflecting the admiration felt towards Ryder by modernist artists of the time who saw his work as a harbinger of American modernist art.[1]

By 1915 Ryder's health deteriorated, and he died on March 28, 1917, at the home of a friend who was caring for him. He was buried at the Rural Cemetery in his birthplace of New Bedford, Massachusetts.

A memorial exhibition of his work was held in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in 1918.[4]

Work and legacy

Ryder completed fewer than two hundred paintings, nearly all of which were created before 1900.[1] He rarely signed and never dated his paintings.[1]

While the works of many of Ryder's contemporaries were partly or mostly forgotten through much of the 20th century, Ryder's artistic reputation has remained largely intact owing to his unique and forward-looking style.[6] Artists whose work was influenced by Ryder include Marsden Hartley, who befriended him,[7] and Jackson Pollock.[8]

Ryder used his materials liberally and with little regard for sound technical procedures. His paintings, which he often worked on for ten years or more, were built up of layers of paint, resin, and varnish applied on top of each other. He would use a wet-on-wet technique,[9] and would often paint into wet varnish, or apply a layer of fast-drying paint over a layer of slow-drying paint. He incorporated unconventional materials, such as candle wax, bitumen, and non-drying oils, into his paintings.[10][11] By these means, Ryder achieved a luminosity that his contemporaries admired—his works seemed to "glow with an inner radiance, like some minerals"—but the result was short-lived.[10] Paintings by Ryder remain unstable and become much darker over time; they develop wide fissures, do not fully dry even after decades, and sometimes completely disintegrate. Many of Ryder's paintings deteriorated significantly even during his lifetime, and he tried to restore them in his later years.[1] Some of his pieces were reworked so many times that they are still soft even a century later.[12] Because of his own restorations, and because some Ryder paintings were completed or reworked by others after his death, many Ryder paintings appear very different today than they did when first created.

Forgeries

In their book, Albert Pinkham Ryder: Painter of Dreams, William Innes Homer and Lloyd Goodrich wrote, "There are more fake Ryders than there are forgeries of any other American artist except his contemporary Ralph Blakelock." The authors, experts on Ryder, estimate the number of forged works at over one thousand. They also claimed (as of 1989) that some remained in private and museum collections, in addition to being offered through art dealers and auction houses. Part of the reason why so many fake Ryders exist is that his style is easily copied. Forgers can go to great lengths to fabricate the age of a painting, including painting it on antique canvas and baking it to add cracks. Forgeries can be discovered through visual and chemical examination, and through a provable provenance—a collection of written documentation detailing a painting's ownership history.[citation needed]

For instance, Ryder's piece, Elegy, while on loan to the Whitney Museum, was examined by Lloyd Goodrich, then a curator at the Whitney. A layer of consistent brushstrokes was revealed through an x-ray examination, which was uncharacteristic of Ryder's often generously layered pieces. It was concluded that Elegy was likely painted to be an imitation of The Lone Horseman, a genuine Ryder piece.[13]

Selected works

- The Lover's Boat c. 1881, Oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.

- The Waste of Waters is Their Field, early 1880s, Brooklyn Museum

- With Sloping Mast and Dipping Prow (late 1880s) oil on canvas, 12 x 12 in. Smithsonian American Art Museum

- The Story of the Cross (mid to late 1880s) oil on canvas on panel, 14 x 11.25 in. Princeton University Art Museum

- The Forest of Arden (1888 - 1897, possibly reworked 1908). Oil on canvas, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

- Seacoast in Moonlight, 1890, the Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

- The Dead Bird, 1890-1900, oil on wood, 4.75 x 10 in. Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.

See also

In popular culture

- The Angel of Darkness by Caleb Carr.

- Ryder and his work are written about at length in Teju Cole’s novel Open City.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Roberts, Norma J., ed. (1988), The American Collections, Columbus Museum of Art, p. 20, ISBN 0-8109-1811-0

- ^ "Albert Pinkham Ryder". The Hotel Albert. 1911-03-11. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ^ "Albert Pinkham Ryder". Retrieved 15 August 2022.

- ^ Loan exhibition of the works of Albert P. Ryder, New York, March 11 to April 14, MCMXVIII, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1918

- ^ Albert Pinkham Ryder, on Metropolitan Museum of Art Collection Database (June 28, 2017)

- ^ See, e.g. Craven, Thomas (December 1927). "An American Master". The American Mercury. pp. 490–497.

- ^ Ludington, Townsend (1992). Marsden Hartley: The Biography of an American Artist. Cornell University Press. pp. 62, 63. ISBN 0801485800.

- ^ Naifeh, Steven; Smith, Gregory White (1989). Jackson Pollock: An American Saga. Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. pp. 250–251, 254. ISBN 0-517-56084-4.

- ^ "In the Stable". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ a b Mayer, Lance, and Gay Myers (2013). American Painters on Technique: 1860–1945. Los Angeles, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 91. ISBN 1606061356.

- ^ Kelly, Franklin, Jr., Nicolai Cikovsky, Deborah Chotner, John Davis, Robert Wilson Torchia, and Ellen G. Miles. (1996). American Paintings of the Nineteenth Century, Part 2. Washington: National Gallery of Art. p. 96. ISBN 0894682547.

- ^ "Jonah". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Smithsonian. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ "Things Aren't What They Seem: Forgeries and Deceptions from the UD Collections". University of Delaware. University of Delaware. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

Further reading

- Stula, Nancy with Nancy Noble. American Artists Abroad and their Inspiration, New London: Lyman Allyn Art Museum, 2004, 64 pages [1]

External links

- Albert Pinkham Ryder at Find a Grave

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.