Aeschylus

Aeschylus | |

|---|---|

Αἰσχύλος | |

Roman marble herma of Aeschylus dating to c. 30 BC, based on an earlier bronze Greek herma, dating to around 340-320 BC | |

| Born | c. 525/524 BC |

| Died | c. 456 BC (aged approximately 67) |

| Occupation(s) | Playwright and soldier |

| Children |

|

| Parent | Euphorion (father) |

| Relatives |

|

Aeschylus (UK: /ˈiːskɪləs/,[1] US: /ˈɛskɪləs/;[2] Ancient Greek: Αἰσχύλος Aischýlos; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian often described as the father of tragedy.[3][4] Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work,[5] and understanding of earlier Greek tragedy is largely based on inferences made from reading his surviving plays.[6] According to Aristotle, he expanded the number of characters in the theatre and allowed conflict among them. Formerly, characters interacted only with the chorus.[nb 1]

Only seven of Aeschylus's estimated 70 to 90 plays have survived in complete form. There is a long-standing debate regarding the authorship of one of them, Prometheus Bound, with some scholars arguing that it may be the work of his son Euphorion. Fragments from other plays have survived in quotations, and more continue to be discovered on Egyptian papyri. These fragments often give further insights into Aeschylus' work.[7] He was likely the first dramatist to present plays as a trilogy. His Oresteia is the only extant ancient example.[8] At least one of his plays was influenced by the Persians' second invasion of Greece (480–479 BC). This work, The Persians, is one of very few classical Greek tragedies concerned with contemporary events, and the only one extant.[9] The significance of the war with Persia was so great to Aeschylus and the Greeks that his epitaph commemorates his participation in the Greek victory at Marathon while making no mention of his success as a playwright.[10]

Life

Aeschylus was born around 525 BC in Eleusis, a small town about 27 kilometres (17 mi) northwest of Athens, in the fertile valleys of western Attica.[11] Some scholars argue that the date of Aeschylus's birth may be based on counting back 40 years from his first victory in the Great Dionysia.[12] His family was wealthy and well established. His father, Euphorion, was said to be a member of the Eupatridae, the ancient nobility of Attica,[13][14] but this might be a fiction invented by the ancients to account for the grandeur of Aeschylus' plays.[15]

As a youth, Aeschylus worked at a vineyard until, according to the 2nd-century AD geographer Pausanias, the god Dionysus visited him in his sleep and commanded him to turn his attention to the nascent art of tragedy.[13] As soon as he woke, he began to write a tragedy, and his first performance took place in 499 BC, when he was 26 years old.[11][13] He won his first victory at the Dionysia in 484 BC.[13][16]

In 510 BC, when Aeschylus was 15 years old, Cleomenes I expelled the sons of Peisistratus from Athens, and Cleisthenes came to power. Cleisthenes' reforms included a system of registration that emphasized the importance of the deme over family tradition. In the last decade of the 6th century, Aeschylus and his family were living in the deme of Eleusis.[17]

The Persian Wars played a large role in Aeschylus' life and career. In 490 BC, he and his brother Cynegeirus fought to defend Athens against the invading army of Darius I of Persia at the Battle of Marathon.[11] The Athenians emerged triumphant, and the victory was celebrated across the city-states of Greece.[11] Cynegeirus was killed while trying to prevent a Persian ship retreating from the shore, for which his countrymen extolled him as a hero.[11][17]

In 480 BC, Aeschylus was called into military service again, together with his younger brother Ameinias, against Xerxes I's invading forces at the Battle of Salamis. Aeschylus also fought at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC.[18] Ion of Chios was a witness for Aeschylus' war record and his contribution in Salamis.[17] Salamis holds a prominent place in The Persians, his oldest surviving play, which was performed in 472 BC and won first prize at the Dionysia.[19]

Aeschylus was one of many Greeks who were initiated into the Eleusinian Mysteries, an ancient cult of Demeter based in his home town of Eleusis.[20] According to Aristotle, Aeschylus was accused of asebeia (impiety) for revealing some of the cult's secrets on stage.[21][22][14]

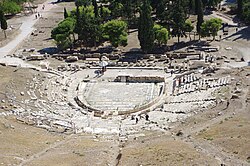

Other sources claim that an angry mob tried to kill Aeschylus on the spot but he fled the scene. Heracleides of Pontus asserts that the audience tried to stone Aeschylus. Aeschylus took refuge at the altar in the orchestra of the Theater of Dionysus. He pleaded ignorance at his trial. He was acquitted, with the jury sympathetic to the military service of him and his brothers during the Persian Wars. According to the 2nd-century AD author Aelian, Aeschylus' younger brother Ameinias helped to acquit Aeschylus by showing the jury the stump of the hand he had lost at Salamis, where he was voted bravest warrior. The truth is that the award for bravery at Salamis went not to Aeschylus' brother but to Ameinias of Pallene.[17]

Aeschylus travelled to Sicily once or twice in the 470s BC, having been invited by Hiero I, tyrant of Syracuse, a major Greek city on the eastern side of the island. He produced The Women of Aetna during one of these trips (in honor of the city founded by Hieron), and restaged his Persians.[11] By 473 BC, after the death of Phrynichus, one of his chief rivals, Aeschylus was the yearly favorite in the Dionysia, winning first prize in nearly every competition.[11] In 472 BC, Aeschylus staged the production that included the Persians, with Pericles serving as choregos.[17]

Personal life

Aeschylus married and had two sons, Euphorion and Euaeon, both of whom became tragic poets. Euphorion won first prize in 431 BC in competition against both Sophocles and Euripides.[23] A nephew of Aeschylus, Philocles (his sister's son), was also a tragic poet, and won first prize in the competition against Sophocles' Oedipus Rex.[17][24] Aeschylus had at least two brothers, Cynegeirus and Ameinias.

Death

In 458 BC, Aeschylus returned to Sicily for the last time, visiting the city of Gela, where he died in 456 or 455 BC. Valerius Maximus wrote that he was killed outside the city by a tortoise dropped by an eagle which had mistaken his head for a rock suitable for shattering the shell, and killed him.[26] Pliny, in his Naturalis Historiæ, adds that Aeschylus had been staying outdoors to avoid a prophecy that he would be killed by a falling object,[26][27] but this story may be legendary and due to a misunderstanding of the iconography on Aeschylus' tomb.[28] Aeschylus' work was so respected by the Athenians that after his death his tragedies were the only ones allowed to be restaged in subsequent competitions.[11] His sons Euphorion and Euæon and his nephew Philocles also became playwrights.[11]

The inscription on Aeschylus' gravestone makes no mention of his theatrical renown, commemorating only his military achievements:

Αἰσχύλον Εὐφορίωνος Ἀθηναῖον τόδε κεύθει

μνῆμα καταφθίμενον πυροφόροιο Γέλας·

ἀλκὴν δ' εὐδόκιμον Μαραθώνιον ἄλσος ἂν εἴποι

καὶ βαθυχαιτήεις Μῆδος ἐπιστάμενος

Beneath this stone lies Aeschylus, son of Euphorion, the Athenian,

who perished in the wheat-bearing land of Gela;

of his noble prowess the grove of Marathon can speak,

and the long-haired Persian knows it well.— Anthologiae Graecae Appendix, vol. 3, Epigramma sepulcrale. p. 17.

Works

The seeds of Greek drama were sown in religious festivals for the gods, chiefly Dionysus, the god of wine.[16] During Aeschylus' lifetime, dramatic competitions became part of the City Dionysia, held in spring.[16] The festival opened with a procession which was followed by a competition of boys singing dithyrambs, and all culminated in a pair of dramatic competitions.[29] The first competition Aeschylus would have participated in involved three playwrights each presenting three tragedies and one satyr play.[29] A second competition involving five comedic playwrights followed, and the winners of both competitions were chosen by a panel of judges.[29]

Aeschylus entered many of these competitions, and various ancient sources attribute between seventy and ninety plays to him.[3][30] Only seven tragedies attributed to him have survived intact: The Persians, Seven Against Thebes, The Suppliants, the trilogy known as The Oresteia (the three tragedies Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers and The Eumenides), and Prometheus Bound (whose authorship is disputed). With the exception of this last play – the success of which is uncertain – all of Aeschylus's extant tragedies are known to have won first prize at the City Dionysia.

The Alexandrian Life of Aeschylus claims that he won the first prize at the City Dionysia thirteen times. This compares favorably with Sophocles' reported eighteen victories (with a substantially larger catalogue, an estimated 120 plays), and dwarfs the five victories of Euripides, who is thought to have written roughly 90 plays.

Trilogies

One hallmark of Aeschylean dramaturgy appears to have been his tendency to write connected trilogies in which each play serves as a chapter in a continuous dramatic narrative.[31] The Oresteia is the only extant example of this type of connected trilogy, but there is evidence that Aeschylus often wrote such trilogies. The satyr plays that followed his tragic trilogies also drew from myth.

The satyr play Proteus, which followed the Oresteia, treated the story of Menelaus' detour in Egypt on his way home from the Trojan War. It is assumed, based on the evidence provided by a catalogue of Aeschylean play titles, scholia, and play fragments recorded by later authors, that three other extant plays of his were components of connected trilogies: Seven Against Thebes was the final play in an Oedipus trilogy, and The Suppliants and Prometheus Bound were each the first play in a Danaid trilogy and Prometheus trilogy, respectively. Scholars have also suggested several completely lost trilogies, based on known play titles. A number of these treated myths about the Trojan War. One, collectively called the Achilleis, comprised Myrmidons, Nereids and Phrygians (alternately, The Ransoming of Hector).

Another trilogy apparently recounted the entrance of the Trojan ally Memnon into the war, and his death at the hands of Achilles (Memnon and The Weighing of Souls being two components of the trilogy). The Award of the Arms, The Phrygian Women, and The Salaminian Women suggest a trilogy about the madness and subsequent suicide of the Greek hero Ajax. Aeschylus seems to have written about Odysseus' return to Ithaca after the war (including his killing of his wife Penelope's suitors and its consequences) in a trilogy consisting of The Soul-raisers, Penelope, and The Bone-gatherers. Other suggested trilogies touched on the myth of Jason and the Argonauts (Argô, Lemnian Women, Hypsipylê), the life of Perseus (The Net-draggers, Polydektês, Phorkides), the birth and exploits of Dionysus (Semele, Bacchae, Pentheus), and the aftermath of the war portrayed in Seven Against Thebes (Eleusinians, Argives (or Argive Women), Sons of the Seven).[32]

Surviving plays

The Persians (472 BC)

The Persians (Persai) is the earliest of Aeschylus' extant plays. It was performed in 472 BC. It was based on Aeschylus' own experiences, specifically the Battle of Salamis.[33] It is unique among surviving Greek tragedies in that it describes a recent historical event.[3] The Persians focuses on the popular Greek theme of hubris and blames Persia's loss on the pride of its king.[33]

It opens with the arrival of a messenger in Susa, the Persian capital, bearing news of the catastrophic Persian defeat at Salamis, to Atossa, the mother of the Persian King Xerxes. Atossa then travels to the tomb of Darius, her husband, where his ghost appears, to explain the cause of the defeat. It is, he says, the result of Xerxes' hubris in building a bridge across the Hellespont, an action which angered the gods. Xerxes appears at the end of the play, not realizing the cause of his defeat, and the play closes to lamentations by Xerxes and the chorus.[34]

Seven Against Thebes (467 BC)

Seven against Thebes (Hepta epi Thebas) was performed in 467 BC. It has the contrasting theme of the interference of the gods in human affairs.[33][clarification needed] Another theme, with which Aeschylus' would continually involve himself, makes its first known appearance in this play, namely that the polis was a key development of human civilization.[35]

The play tells the story of Eteocles and Polynices, the sons of the shamed king of Thebes, Oedipus. Eteocles and Polynices agree to share and alternate the throne of the city. After the first year, Eteocles refuses to step down. Polynices therefore undertakes war. The pair kill each other in single combat, and the original ending of the play consisted of lamentations for the dead brothers.[36] But a new ending was added to the play some fifty years later: Antigone and Ismene mourn their dead brothers, a messenger enters announcing an edict prohibiting the burial of Polynices, and Antigone declares her intention to defy this edict.[36] The play was the third in a connected Oedipus trilogy. The first two plays were Laius and Oedipus. The concluding satyr play was The Sphinx.[37]

The Suppliants (463 BC)

Aeschylus continued his emphasis on the polis with The Suppliants (Hiketides) in 463 BC. The play gives tribute to the democratic undercurrents which were running through Athens and preceding the establishment of a democratic government in 461. The Danaids (50 daughters of Danaus, founder of Argos) flee a forced marriage to their cousins in Egypt.[clarification needed] They turn to King Pelasgus of Argos for protection, but Pelasgus refuses until the people of Argos weigh in on the decision (a distinctly democratic move on the part of the king). The people decide that the Danaids deserve protection and are allowed within the walls of Argos despite Egyptian protests.[38]

A Danaid trilogy had long been assumed because of The Suppliants' cliffhanger ending. This was confirmed by the 1952 publication of Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 2256 fr. 3. The constituent plays are generally agreed to be The Suppliants and The Egyptians and The Danaids. A plausible reconstruction of the trilogy's last two-thirds runs thus:[39] In The Egyptians, the Argive-Egyptian war threatened in the first play has transpired. King Pelasgus was killed during the war, and Danaus rules Argos. Danaus negotiates a settlement with Aegyptus, a condition of which requires his 50 daughters to marry the 50 sons of Aegyptus. Danaus secretly informs his daughters of an oracle which predicts that one of his sons-in-law would kill him. He orders the Danaids to murder their husbands therefore on their wedding night. His daughters agree. The Danaids would open the day after the wedding.[40]

It is revealed that 49 of the 50 Danaids killed their husbands. Hypermnestra did not kill her husband, Lynceus, and helped him escape. Danaus is angered by his daughter's disobedience and orders her imprisonment and possibly execution. In the trilogy's climax and dénouement, Lynceus reveals himself to Danaus and kills him, thus fulfilling the oracle. He and Hypermnestra will establish a ruling dynasty in Argos. The other 49 Danaids are absolved of their murders, and married off to unspecified Argive men. The satyr play following this trilogy was titled Amymone, after one of the Danaids.[40]

The Oresteia (458 BC)

Besides a few missing lines, the Oresteia of 458 BC is the only complete trilogy of Greek plays by any playwright still extant (of Proteus, the satyr play which followed, only fragments are known).[33] Agamemnon and The Libation Bearers (Choephoroi) and The Eumenides[35] together tell the violent story of the family of Agamemnon, king of Argos.

Agamemnon

Aeschylus begins in Greece, describing the return of King Agamemnon from his victory in the Trojan War, from the perspective of the townspeople (the Chorus) and his wife, Clytemnestra. Dark foreshadowings build to the death of the king at the hands of his wife, who was angry that their daughter Iphigenia was killed so that the gods would restore the winds and allow the Greek fleet to sail to Troy. Clytemnestra was also unhappy that Agamemnon kept the Trojan prophetess Cassandra as his concubine. Cassandra foretells the murder of Agamemnon and of herself to the assembled townsfolk, who are horrified. She then enters the palace knowing that she cannot avoid her fate. The ending of the play includes a prediction of the return of Orestes, son of Agamemnon, who will seek to avenge his father.[35]

The Libation Bearers

The Libation Bearers opens with Orestes' arrival at Agamemnon's tomb, from exile in Phocis. Electra meets Orestes there. They plan revenge against Clytemnestra and her lover, Aegisthus. Clytemnestra's account of a nightmare in which she gives birth to a snake is recounted by the chorus. This leads her to order her daughter, Electra, to pour libations on Agamemnon's tomb (with the assistance of libation bearers) in hope of making amends. Orestes enters the palace pretending to bear news of his own death. Clytemnestra calls in Aegisthus to learn the news. Orestes kills them both. Orestes is then beset by the Furies, who avenge the murders of kin in Greek mythology.[35]

The Eumenides

The third play addresses the question of Orestes' guilt.[35] The Furies drive Orestes from Argos and into the wilderness. He makes his way to the temple of Apollo and begs Apollo to drive the Furies away. Apollo had encouraged Orestes to kill Clytemnestra, so he bears some of the guilt for the murder. Apollo sends Orestes to the temple of Athena with Hermes as a guide.[38]

The Furies track him down, and Athena steps in and declares that a trial is necessary. Apollo argues Orestes' case, and after the judges (including Athena) deliver a tie vote, Athena announces that Orestes is acquitted. She renames the Furies The Eumenides (The Good-spirited, or Kindly Ones), and extols the importance of reason in the development of laws. As in The Suppliants, the ideals of a democratic Athens are praised.[38]

Prometheus Bound (date disputed)

Prometheus Bound is attributed to Aeschylus by ancient authorities. Since the late 19th century, however, scholars have increasingly doubted this ascription, largely on stylistic grounds. Its production date is also in dispute, with theories ranging from the 480s BC to as late as the 410s.[11][41]

The play consists mostly of static dialogue.[clarification needed] The Titan Prometheus is bound to a rock throughout, which is his punishment from the Olympian Zeus for providing fire to humans. The god Hephaestus and the Titan Oceanus and the chorus of Oceanids all express sympathy for Prometheus' plight. Prometheus is met by Io, a fellow victim of Zeus' cruelty. He prophesies her future travels, revealing that one of her descendants will free Prometheus. The play closes with Zeus sending Prometheus into the abyss because Prometheus will not tell him of a potential marriage which could prove Zeus' downfall.[34]

Prometheus Bound seems to have been the first play in a trilogy, the Prometheia. In the second play, Prometheus Unbound, Heracles frees Prometheus from his chains and kills the eagle that had been sent daily to eat Prometheus' perpetually regenerating liver, then believed the source of feeling.[42] We learn that Zeus has released the other Titans which he imprisoned at the conclusion of the Titanomachy, perhaps foreshadowing his eventual reconciliation with Prometheus.[43]

In the trilogy's conclusion, Prometheus the Fire-Bringer, it seems that the Titan finally warns Zeus not to sleep with the sea nymph Thetis, for she is fated to beget a son greater than the father. Not wishing to be overthrown, Zeus marries Thetis off to the mortal Peleus. The product of that union is Achilles, Greek hero of the Trojan War. After reconciling with Prometheus, Zeus probably inaugurates a festival in his honor at Athens.[43]

Lost plays

Of Aeschylus' other plays, only titles and assorted fragments are known. There are enough fragments (along with comments made by later authors and scholiasts) to produce rough synopses for some plays.

Myrmidons

This play was based on books 9 and 16 of the Iliad. Achilles sits in silent indignation over his humiliation at Agamemnon's hands for most of the play.[clarification needed] Envoys from the Greek army attempt to reconcile Achilles to Agamemnon, but he yields only to Patroclus, who then battles the Trojans in Achilles' armour. The bravery and death of Patroclus are reported in a messenger's speech, which is followed by mourning.[17]

Nereids

This play was based on books 18 and 19 and 22 of the Iliad. It follows the Daughters of Nereus, the sea god, who lament Patroclus' death. A messenger tells how Achilles (perhaps reconciled to Agamemnon and the Greeks) slew Hector.[17]

Phrygians, or Hector's Ransom

After a brief discussion with Hermes, Achilles sits in silent mourning over Patroclus. Hermes then brings in King Priam of Troy, who wins over Achilles and ransoms his son's body in a spectacular coup de théâtre. A scale is brought on stage and Hector's body is placed in one scale and gold in the other. The dynamic dancing of the chorus of Trojans when they enter with Priam is reported by Aristophanes.[17]

Niobe

The children of Niobe, the heroine, have been slain by Apollo and Artemis because Niobe had gloated that she had more children than their mother, Leto. Niobe sits in silent mourning on stage during most of the play. In the Republic, Plato quotes the line "God plants a fault in mortals when he wills to destroy a house utterly."[17]

These are the remaining 71 plays ascribed to Aeschylus which are known:[citation needed]

- Alcmene

- Amymone

- The Archer-Women

- The Argivian Women

- The Argo, also titled The Rowers

- Atalanta

- Athamas

- Attendants of the Bridal Chamber

- Award of the Arms

- The Bacchae

- The Bassarae

- The Bone-Gatherers

- The Cabeiroi

- Callisto

- The Carians, also titled Europa

- Cercyon

- Children of Hercules

- Circe

- The Cretan Women

- Cycnus

- The Danaids

- Daughters of Helios

- Daughters of Phorcys

- The Descendants

- The Edonians

- The Egyptians

- The Escorts

- Glaucus of Pontus

- Glaucus of Potniae

- Hypsipyle

- Iphigenia

- Ixion

- Laius

- The Lemnian Women

- The Lion

- Lycurgus

- Memnon

- The Men of Eleusis

- The Messengers

- The Myrmidons

- The Mysians

- Nemea

- The Net-Draggers

- The Nurses of Dionysus

- Orethyia

- Palamedes

- Penelope

- Pentheus

- Perrhaibides

- Philoctetes

- Phineus

- The Phrygian Women

- Polydectes

- The Priestesses

- Prometheus the Fire-Bearer

- Prometheus the Fire-Kindler

- Prometheus Unbound

- Proteus

- Semele, also titled The Water-Bearers

- Sisyphus the Runaway

- Sisyphus the Stone-Roller

- The Spectators, also titled Athletes of the Isthmian Games

- The Sphinx

- The Spirit-Raisers

- Telephus

- The Thracian Women

- Weighing of Souls

- Women of Aetna (two versions)

- Women of Salamis

- Xantriae

- The Youths

Influence

Influence on Greek drama and culture

The theatre was just beginning to evolve when Aeschylus started writing for it. Earlier playwrights such as Thespis had already expanded the cast to include an actor who was able to interact with the chorus.[30] Aeschylus added a second actor, allowing for greater dramatic variety, while the chorus played a less important role.[30] He is sometimes credited with introducing skenographia, or scene-decoration,[44] though Aristotle gives this distinction to Sophocles.[45] Aeschylus is also said to have made the costumes more elaborate and dramatic, and made his actors wear platform boots (cothurni) to make them more visible to the audience.[46] According to a later account of Aeschylus' life, the chorus of Furies in the first performance of the Eumenides were so frightening when they entered that children fainted and patriarchs urinated and pregnant women went into labour.[47]

Aeschylus wrote his plays in verse. No violence is performed onstage. The plays have a remoteness from daily life in Athens, relating stories about the gods, or being set, like The Persians, far away.[48] Aeschylus' work has a strong moral and religious emphasis.[48] The Oresteia trilogy concentrated on humans' position in the cosmos relative to the gods and divine law and divine punishment.[49]

Aeschylus' popularity is evident in the praise that the comic playwright Aristophanes gives him in The Frogs, produced some 50 years after Aeschylus' death. Aeschylus appears as a character in the play and claims, at line 1022, that his Seven against Thebes "made everyone watching it to love being warlike".[50] He claims, at lines 1026–7, that with The Persians he "taught the Athenians to desire always to defeat their enemies."[50] Aeschylus goes on to say, at lines 1039ff., that his plays inspired the Athenians to be brave and virtuous.

Influence outside Greek culture

Aeschylus' works were influential beyond his own time. Hugh Lloyd-Jones draws attention to Richard Wagner's reverence of Aeschylus. Michael Ewans argues in his Wagner and Aeschylus. The Ring and the Oresteia (London: Faber. 1982) that the influence was so great as to merit a direct character by character comparison between Wagner's Ring and Aeschylus's Oresteia. But a critic of that book, while not denying that Wagner read and respected Aeschylus, has described the arguments as unreasonable and forced.[51]

J.T. Sheppard argues in the second half of his Aeschylus and Sophocles: Their Work and Influence that Aeschylus and Sophocles have played a major part in the formation of dramatic literature from the Renaissance to the present, specifically in French and Elizabethan drama.[clarification needed] He also claims that their influence went beyond just drama and applies to literature in general, citing Milton and the Romantics.[52]

Eugene O'Neill's Mourning Becomes Electra (1931), a trilogy of three plays set in America after the Civil War, is modeled after the Oresteia. Before writing his[clarification needed] acclaimed trilogy, O'Neill had been developing a play about Aeschylus, and he noted that Aeschylus "so changed the system of the tragic stage that he has more claim than anyone else to be regarded as the founder (Father) of Tragedy."[53]

During his presidential campaign in 1968, Senator Robert F. Kennedy quoted the Edith Hamilton translation of Aeschylus on the night of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. Kennedy was notified of King's murder before a campaign stop in Indianapolis, Indiana, and was warned not to attend the event due to fears of rioting from the mostly African-American crowd. Kennedy insisted on attending and delivered an impromptu speech that delivered news of King's death.[54][55] Acknowledging the audience's emotions, Kennedy referred to his own grief at the murder of Martin Luther King and, quoting a passage from the play Agamemnon (in translation), said: "My favorite poet was Aeschylus. And he once wrote: 'Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.' What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence and lawlessness; but is love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or whether they be black ... Let us dedicate ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world."[56] [57] The quotation from Aeschylus was later inscribed on a memorial at the gravesite of Robert Kennedy following his own assassination.[54]

Editions

- Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Aeschyli Tragoediae. Editio maior, Berlin 1914.

- Gilbert Murray, Aeschyli Septem Quae Supersunt Tragoediae. Editio Altera, Oxford 1955.

- Denys Page, Aeschyli Septem Quae Supersunt Tragoediae, Oxford 1972.

- Martin L. West, Aeschyli Tragoediae cum incerti poetae Prometheo, 2nd ed., Stuttgart/Leipzig 1998.

- The first translation of the seven plays into English was by Robert Potter in 1779, using blank verse for the iambic trimeters and rhymed verse for the choruses, a convention adopted by most translators for the next century.

- Anna Swanwick produced a verse translation in English of all seven surviving plays as The Dramas of Aeschylus in 1886 full text

- Stefan Radt (ed.), Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta. Vol. III: Aeschylus (Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009) (Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta, 3).

- Alan H. Sommerstein (ed.), Aeschylus, Volume II, Oresteia: Agamemnon. Libation-bearers. Eumenides. 146 (Cambridge, Massachusetts/London: Loeb Classical Library, 2009); Volume III, Fragments. 505 (Cambridge, Massachusetts/London: Loeb Classical Library, 2008).

See also

- 2876 Aeschylus, an asteroid named for him

- Ancient Greek literature

- Ancient Greek mythology

- Ancient Greek religion

- Battle of Marathon

- Classical Greece

- Dionysia

- Music of ancient Greece

- Theatre of ancient Greece

- "Live by the sword, die by the sword"

Notes

- ^ The remnant of a commemorative inscription, dated to the 3rd century BC, lists four, possibly eight, dramatic poets (probably including Choerilus, Phrynichus, and Pratinas) who had won tragic victories at the Dionysia before Aeschylus had. Thespis was traditionally regarded the inventor of tragedy. According to another tradition, tragedy was established in Athens in the late 530s BC, but that may simply reflect an absence of records. Major innovations in dramatic form, credited to Aeschylus by Aristotle and the anonymous source The Life of Aeschylus, may be exaggerations and should be viewed with caution (Martin Cropp (2006), "Lost Tragedies: A Survey" in A Companion to Greek Tragedy, pp. 272–74)

Citations

- ^ Jones, Daniel; Roach, Peter, James Hartman and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th edition. Cambridge UP, 2006.

- ^ "Aeschylus". Webster's New World College Dictionary.

- ^ a b c Freeman 1999, p. 243

- ^ Schlegel, August Wilhelm von (December 2004). Lectures on Dramatic Art and Literature. p. 121.

- ^ R. Lattimore, Aeschylus I: Oresteia, 4

- ^ Martin Cropp, 'Lost Tragedies: A Survey'; A Companion to Greek Tragedy, p. 273

- ^ P. Levi, Greek Drama, 159

- ^ S. Saïd, Aeschylean Tragedy, 215

- ^ S. Saïd, Aeschylean Tragedy, 221

- ^ "Pausanias, Description of Greece, *)attika/, chapter 14, section 5". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sommerstein 2010.

- ^ Grene, David, and Richmond Lattimore, eds. The Complete Greek Tragedies: Vol. 1, Aeschylus. University of Chicago Press, 1959.

- ^ a b c d Bates 1906, pp. 53–59

- ^ a b Sidgwick 1911, p. 272

- ^ S. Saïd, Eschylean tragedy, 217

- ^ a b c Freeman 1999, p. 241

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kopff 1997 pp. 1–472

- ^ "§ 4". Anonymous Life of Aeschylus. Living Poets. Translated by S. Burges Watson. Durham. 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

They say that he was noble and that he participated in the battle of Marathon together with his brother, Cynegirus, and in the naval battle at Salamis with the youngest of his brothers, Ameinias, and in the infantry battle at Plataea.

(emphasis in original) - ^ Sommerstein 2010, p. 34

- ^ Martin 2000, §10.1

- ^ Nicomachean Ethics 1111a8–10.

- ^ Filonik, J. (2013). Athenian impiety trials: a reappraisal. Dike-Rivista di Storia del Diritto Greco ed Ellenistico, 16, page 23.

- ^ Osborn, K.; Burges, D. (1998). The complete idiot's guide to classical mythology. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-02-862385-6.

- ^ Smith 2005, p. 1

- ^ Ursula Hoff (1938). "Meditation in Solitude". Journal of the Warburg Institute. 1 (44): 292–294. doi:10.2307/749994. JSTOR 749994. S2CID 192234608.

- ^ a b J. C. McKeown (2013), A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization, Oxford University Press, p. 136, ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3,

The unusual nature of Aeschylus' death ...

- ^ Pliny the Elder. "Book X, Chapter 3". The Natural History.

This eagle has the instinct to break the shell of the tortoise by letting it fall from aloft, a circumstance which caused the death of the poet Æschylus. An oracle, it is said, had predicted his death on that day by the fall of a house, upon which he took the precaution of trusting himself only under the canopy of the heavens.

- ^ Critchley 2009

- ^ a b c Freeman 1999, p. 242

- ^ a b c Pomeroy 1999, p. 222

- ^ Sommerstein 2010

- ^ Sommerstein 2010, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Freeman 1999, p. 244

- ^ a b Vellacott: 7–19

- ^ a b c d e Freeman 1999, pp. 244–46

- ^ a b Aeschylus. "Prometheus Bound, The Suppliants, Seven Against Thebes, The Persians." Philip Vellacott's Introduction, pp. 7–19. Penguin Classics.

- ^ Sommerstein 2002, 23.

- ^ a b c Freeman 1999, p. 246

- ^ See (e.g.) Sommerstein 1996, 141–51; Turner 2001, 36–39.

- ^ a b Sommerstein 2002, 89.

- ^ Griffith 1983, pp. 32–34

- ^ For example: Agamemnon 432 "Many things pierce the liver"; 791–2 "No sting of true sorrow reaches the liver"; Eumenides 135 "Sting your liver with merited reproaches".

- ^ a b For a discussion of the trilogy's reconstruction, see (e.g.) Conacher 1980, 100–02.

- ^ According to Vitruvius. See Summers 2007, 23.

- ^ Performance in Greek and Roman theatre. George William Mallory Harrison, Vaios Liapēs. Leiden: Brill. 2013. p. 111. ISBN 978-90-04-24545-7. OCLC 830001324.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Aeschylus". PoemHunter. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Life of Aeschylus.

- ^ a b Pomeroy 1999, p. 223

- ^ Pomeroy 1999, pp. 224–25

- ^ a b Scharffenberger, Elizabeth W. (2007). ""Deinon Eribremetas": The Sound and Sense of Aeschylus in Aristophanes' "Frogs"". The Classical World. 100 (3): 229–249. ISSN 0009-8418. JSTOR 25434023.

- ^ Furness, Raymond (January 1984). "Reviewed work: Wagner and Aeschylus. The 'Ring' and the 'Oresteia', Michael Ewans". The Modern Language Review. 79 (1): 239–40. doi:10.2307/3730399. JSTOR 3730399.

- ^ Sheppard, J. T. (1927). "Aeschylus and Sophocles: their Work and Influence". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 47 (2): 265. doi:10.2307/625177. JSTOR 625177.

- ^ Floyd, Virginia, ed. Eugene O'Neill at Work. New York: Frederick Ungar, 1981, p. 213. ISBN 0-8044-2205-2

- ^ a b "Virginia – Arlington National Cemetery: Robert F. Kennedy Gravesite". 7 June 2009.

- ^ "Robert Kennedy: Delivering News of King's Death". National Public Radio. 4 April 2008. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, Maxwell Taylor (1998). Make Gentle the Life of This World: The Vision of Robert F. Kennedy. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-100-356-4.

- ^ Kennedy, Robert F. (4 April 1968). "Statement on Assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr". The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum. Papers of Robert F. Kennedy. Senate Papers. Speeches and Press Releases, Box 4, "4/1/68 - 4/10/68." John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. Retrieved 6 July 2024.

References

- Bates, Alfred (1906). The Drama: Its History, Literature, and Influence on Civilization. Vol. 1. London: Historical Publishing Company.

- Bierl, A. Die Orestie des Aischylos auf der modernen Bühne: Theoretische Konzeptionen und ihre szenische Realizierung (Stuttgart: Metzler, 1997)

- Cairns, D., V. Liapis, Dionysalexandros: Essays on Aeschylus and His Fellow Tragedians in Honour of Alexander F. Garvie (Swansea: The Classical Press of Wales, 2006)

- Critchley, Simon (2009). The Book of Dead Philosophers. London: Granta Publications. ISBN 978-1-84708079-0.

- Cropp, Martin (2006). "Lost Tragedies: A Survey". In Gregory, Justine (ed.). A Companion to Greek Tragedy. Blackwell Publishing.

- Deforge, B. Une vie avec Eschyle. Vérité des mythes (Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2010)

- Freeman, Charles (1999). The Greek Achievement: The Foundation of the Western World. New York City: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-88515-2.

- Goldhill, Simon (1992). Aeschylus, The Oresteia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-40293-4.

- Griffith, Mark (1983). Aeschylus' Prometheus Bound. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27011-3.

- Herington, C.J. (1986). Aeschylus. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03562-9.

- Herington, C.J. (1967). "Aeschylus in Sicily". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 87: 74–85. doi:10.2307/627808. JSTOR 627808. S2CID 162400889.

- Kopff, E. Christian (1997). Ancient Greek Authors. Gale. ISBN 978-0-8103-9939-6.

- Lattimore, Richmond (1953). Aeschylus I: Oresteia. University of Chicago Press.

- Lefkowitz, Mary (1981). The Lives of the Greek Poets. University of North Carolina Press

- Lesky, Albin (1979). Greek Tragedy. London: Benn.

- Lesky, Albin (1966). A History of Greek Literature. New York: Crowell.

- Levi, Peter (1986). "Greek Drama". The Oxford History of the Classical World. Oxford University Press.

- Martin, Thomas (2000). Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times. Yale University Press.

- Murray, Gilbert (1978). Aeschylus: The Creator of Tragedy. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Podlecki, Anthony J. (1966). The Political Background of Aeschylean Tragedy. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. (1999). Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509743-6.

- Rosenmeyer, Thomas G. (1982). The Art of Aeschylus. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04440-1.

- Saïd, Suzanne (2006). "Aeschylean Tragedy". A Companion to Greek Tragedy. Blackwell Publishing.

- Sidgwick, Arthur (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 272–276.

- Smith, Helaine (2005). Masterpieces of Classic Greek Drama. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-33268-5.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1922). Aeschylus. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Sommerstein, Alan H. (2010). Aeschylean Tragedy (2nd ed.). London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3824-8.

- — (2002). Greek Drama and Dramatists. London: Routledge Press. ISBN 0-415-26027-2

- Spatz, Lois (1982). Aeschylus. Boston: Twayne Publishers Press. ISBN 978-0-8057-6522-9.

- Summers, David (2007). Vision, Reflection, and Desire in Western Painting. University of North Carolina Press

- Thomson, George (1973) Aeschylus and Athens: A Study in the Social Origin of Drama. London: Lawrence and Wishart (4th edition)

- Turner, Chad (2001). "Perverted Supplication and Other Inversions in Aeschylus' Danaid Trilogy". Classical Journal. 97 (1): 27–50. JSTOR 3298432.

- Vellacott, Philip, (1961). Prometheus Bound and Other Plays: Prometheus Bound, Seven Against Thebes, and The Persians. New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044112-3

- Winnington-Ingram, R. P. (1985). "Aeschylus". The Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek Literature. Cambridge University Press.

- Zeitlin, Froma (1982). Under the sign of the shield: semiotics and Aeschylus' Seven against Thebes. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books, 2nd ed. 2009 (Greek studies: interdisciplinary approaches)

- Zetlin, Froma (1996). "The dynamics of misogyny: myth and mythmaking in Aeschylus's Oresteia", in Froma Zeitlin, Playing the Other: Gender and Society in Classical Greek Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 87–119.

- Zeitlin, Froma (1996). "The politics of Eros in the Danaid trilogy of Aeschylus", in Froma Zeitlin, Playing the Other: Gender and Society in Classical Greek Literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 123–171.

External links

- Works by Aeschylus at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Aeschylus in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Aeschylus (translated by George Gilbert Aimé) at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Aeschylus at the Internet Archive

- Works by Aeschylus at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Selected Poems of Aeschylus

- Aeschylus-related materials at the Perseus Digital Library

- Complete syntax diagrams at Alpheios

- Online English Translations of Aeschylus

- Photo of a fragment of The Net-pullers

- Crane, Gregory. "Aeschylus (4)". Perseus Encyclopedia.

- "Aeschylus, I: Persians" from the Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press

- "Aeschylus, II: The Oresteia" from the Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press

- "Aeschylus, III: Fragments" from the Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press