Land reform in Mexico

Before the 1910 Mexican Revolution, most land in post-independence Mexico was owned by wealthy Mexicans and foreigners, with small holders and indigenous communities possessing little productive land. During the colonial era, the Spanish crown protected holdings of indigenous communities that were mostly engaged in subsistence agriculture to countervail the encomienda and repartimiento systems. In the 19th century, Mexican elites consolidated large landed estates (haciendas) in many parts of the country while small holders, many of whom were mixed-race mestizos, engaged with the commercial economy.

After the War of Independence, Mexican liberals sought to modernize the economy, promoting commercial agriculture through the dissolution of common lands, most of which were then property of the Catholic Church, and indigenous communities. When liberals came to power in the mid nineteenth century, they implemented laws that mandated the breakup and sale of these corporate lands. When liberal general Porfirio Díaz took office in 1877, he embarked on a more sweeping program of modernization and economic development. His land policies sought to attract foreign investment to Mexican mining, agriculture, and ranching, resulting in Mexican and foreign investors controlling the majority of Mexican territory by the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Peasant mobilization against landed elites during the revolution prompted land reform in the post-revolutionary period and led to the creation of the ejido system, enshrined in the Mexican Constitution of 1917.[1][2][3]

During the first five years of agrarian reform, very few hectares were distributed.[4] Land reform attempts by past leaders and governments proved futile, as the revolution from 1910 to 1920 had been a battle of dependent labor, capitalism, and industrial ownership.[5] Fixing the agrarian problem was a question of education, methods, and creating new social relationships through co-operative effort and government assistance.[6] Initially the agrarian reform led to the development of many ejidos for communal land use, while parceled ejidos emerged in the later years.[7] Land reform in Mexico ended in 1991 after the Chamber of Deputies amended Article 27 of the Constitution.[8]

History of land tenure in Central Mexico

Prehispanic era

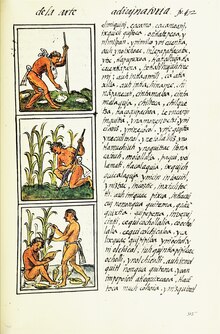

The rich lands of central and southern Mexico were the home to dense, hierarchically organized, settled populations that produced agricultural surpluses, allowing the development of sectors that did not directly cultivate the soil. These populations lived in settlements and held land in common, although generally they worked individual plots. During the Aztec period, roughly 1450 to 1521, the Nahuas of central Mexico had names for civil categories of land, many of which persisted into the colonial era.[9] There were special lands attached to the office of ruler (tlatoani) called tlatocatlalli; land devoted to the support of temples, tecpantlalli, but also private lands of the nobility, pillalli. Lands owned by the calpulli, the local kin-based social organization, were calpullalli.[10][11] Most commoners held individual plots of land, often in scattered locations, which were worked by a family and rights passed to subsequent generations. A community member could lose those usufruct rights if they did not cultivate the land. A person could lose land as a result of gambling debts,[12] a type of alienation from which the inference can be drawn that land was private property.

It is important to note that there were lands classified as "purchased land" (in Nahuatl, tlalcohualli).[13] In the Texcoco area, there were prehispanic legal rules for land sales, indicating that transfers by sale were not a post-conquest innovation.[14] Local-level records in Nahuatl from the 16th century show that individuals and community members kept track of these categories, including purchased land, and often the previous owners of particular plots.[15][16]

Colonial era

After the Spanish conquest of central Mexico in the early 16th century, indigenous land tenure was initially left intact, with the exception of the disappearance of lands devoted to the gods.[17] A 16th-century Spanish judge in New Spain, Alonso de Zorita, collected extensive information about the Nahuas in the Cuauhtinchan region, including land tenure.[18][19] Zorita notes there was a diversity of land tenure in central Mexico, so that if the information he gives for one place contradicts information in another it is due to that very diversity.[20] Zorita, along with Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, a member of the noble family that ruled Texcoco, and Franciscan Fray Juan de Torquemada are the most important sources for prehispanic and early colonial indigenous land tenure in central Mexico.[21]

There is considerable documentation on indigenous land holding, including estates held by indigenous lords (caciques), known as cacicazgos. Litigation over title to property date from the very early colonial era. Most notable is the dispute over lands held by don Carlos Ometochtzin of Texcoco, who was executed by the inquisition in 1539. The Oztoticpac Lands Map of Texcoco is documentation for the dispute following his death.[22]

In early colonial Mexico, many Spanish conquerors (and a few indigenous allies) received grants of labor and tribute from particular indigenous communities as rewards for services via an institution called encomienda. These grants did not include land, which in the immediate post-conquest era was not as important as the tribute and labor service that Indians could provide as a continuation from the prehispanic period. Spaniards were interested in appropriating products and labor from their grants, but they saw no need to acquire the land itself. The crown began to phase out the encomienda in the mid-16th century, limiting the number of times the grant could be inherited. At the same time, decreases in indigenous populations and Spanish migration to Mexico created a demand for foodstuffs familiar to them, such as wheat rather than maize, European fruits, and animals such as cattle, sheep, and goats for meat and hides or wool. Spaniards began acquiring land and securing labor separate from the encomienda grants. This was the initial stage of the formation of Spanish landed estates.[23][24]

Spaniards bought land from individual Indians and from Indian communities; they also usurped Indians’ land; and they occupied land that was deemed "empty" (terrenos baldíos) and requested grants (mercedes) to acquire title to it. There is evidence that nobles sold common land to Spaniards, treating that land as private property.[25] Some Indians were alarmed at this transfer of land, and explicitly forbade sale of land to Spaniards.[26]

The Spanish crown was concerned about the material welfare of its indigenous vassals and in 1567 set aside an endowment of land adjacent to Indian towns that were legally held by the community, the fundo legal, initially 500 varas.[27][28] The legal framework for these entailed indigenous community lands was the establishment of settlements (designated pueblos de indios or merely pueblos) as legal entities in Spanish colonial law, with a framework for rule established with via the town council (cabildo).[29] Land traditionally held by pueblos was now transformed to entailed community lands.[30][31] There was not a unitary process of the creation of these lands, but a combination of claims based on occupation and use since time immemorial, grants, purchase, and a process of regularization of land titles via a process known as composición.[32]

To protect Indians' legal rights, the Spanish crown also set up the General Indian Court in 1590, where Indians and indigenous communities could litigate over property. Although the Juzgado de Naturales supposedly did not have jurisdiction in cases where Indians sought redress against Spaniards, an analysis of the actual cases shows that a high percentage of the court's casework included such complaints.[33] For the Spanish crown, the court not only protected the interests of its Indian vassals, but it was also a way to rein in Spaniards who might seek greater autonomy from the crown.[34]

Indian communities experienced devastating population losses due to epidemics, which meant that there was for a period more land than individual Indians or Indian communities needed.[citation needed] The crown attempted to cluster remaining indigenous populations, relocating them in new communities in a process known as congregacion or reducción, with mixed results. During this period Spaniards acquired land, often with no immediate damage to Indians’ access to land. In the 17th century, Indian populations began to recover, but the loss of land could not be reversed. Indian communities rented land to Spanish haciendas, which over time left those lands vulnerable to appropriation. There were crown regulations about sale or rental of Indian lands, with requirements for the public posting of the proposed transaction and an investigation as to whether the land on offer was, in fact, the property of the ones offering it.[35]

Since the crown held title to all vacant land in Central Mexico, it could grant title to whomever it chose. In theory, there was to be an investigation to see if there were claims on the property, with notice given to those in the vicinity of the proposed grant.[36] The Spanish crown granted mercedes to favored Spaniards, and in the case of the conqueror Hernán Cortés, created the entailment of the Marquesado del Valle de Oaxaca.

In the 17th century, there was a push to regularize land titles via the process of composición, in which for a fee paid to the crown clouded titles could be cleared, and indigenous communities had to prove title to land that they had held "since time immemorial," as the legal phrase went.[37] This was the period when Spaniards began regularizing their titles via composición.[17]

In the 18th century, the Spanish crown was concerned about concentration of land in the hands of a few in Spain and the lack of productiveness of those landed estates. Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos drafted the Informe para una ley Agraria ("A report for an Agrarian Law") published in 1795 for the Royal Society of Friends of the Country of Madrid ("es:Real Sociedad Económica Matritense de Amigos del País") calling for reform. He saw the need for disentailment of landed estates, sale of land owned by the Catholic Church and privatizing common lands as key to making agriculture more productive in Spain.[38] Barriers to productive use of land and a real estate market that would attract investors kept land scare and prices high and for investors was not a profitable enough enterprise to enter agriculture.[39] Jovellanos was influenced by Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776), which asserted that the impetus for economic activity was self-interest.[40]

Jovellanos’s writings influenced (without attribution) a prominent cleric in independence-era New Spain, Manuel Abad y Queipo, who compiled copious data about the agrarian situation in the late 18th century and who conveyed it to Alexander von Humboldt. Humboldt incorporated it into his Political Essay on the Kingdom of New Spain,[41] an important text on economic and social conditions in New Spain around 1800. Abad y Queipo "fixed upon the inequitable distribution of property as the chief cause of New Spain’s social squalor and advocated ownership of land as the chief remedy."[41]

The crown did not undertake major land reform in New Spain, but it moved against the wealthy and influential Society of Jesus in its realms, expelling them in 1767. In Mexico, the Jesuits had created prosperous haciendas whose profits helped fund the Jesuits’ missions in northern Mexico and its colegios for elite American-born Spaniards. The most well-studied of the Jesuit haciendas in Mexico is that Santa Lucía.[42] With their expulsion, their estates were sold, mainly to private-land owning elites.[43] Although the Jesuits owned and ran large estates, in Mexico the more common pattern was for the Church to extend credit to private individuals of means for long-term real estate mortgages.[44] Small holders had little access to credit, which meant it was difficult for them to acquire property or expand their operations, thereby privileging large land owners over small.

The landed elite and the Catholic Church as an institution were closely connected financially. The church was the recipient of donations for pious works (obras pías) for particular charities as well as chantries (capellanías). Through the institution of the chantry, a family would lien income from a particular piece of property to pay a priest to say masses for the soul of the one endowing the funds. In many cases, families had sons who had become priests and the chantry became a source of income for the family member. At the turn of the 19th century the Spanish crown attempted to tap what it thought was the vast wealth of the church by demanding that those holding mortgages pay the principal as a lump sum immediately rather than incrementally over the long term. The Act of Consolidation in 1804 threatened to bring down the whole structure of credit to landed elites who were seldom in the position of enough liquidity. Bishop-elect of Michoacan Manuel Abad y Queipo protested the crown's demands and drafted a lengthy memorial to the crown analyzing the situation. From the point of view of the landed elite, the crown's demands were "a savage capital levy" which would "destroy the country’s credit system and drain the economy of its currency."[45]

The availability of credit had enabled haciendas to increase in size, but they were not efficiently run in general, with much land not planted. Hacienda owners were reluctant to lease lands to Indians for fear that they would then claim land as part of the fundo legal for a newly established community.[46] Abad y Queipo concluded "The indivisibility of haciendas, the difficulty in managing them, the lack of property among the people, has produced and continues to produce deplorable effects for agriculture, for the population, and for the State in general."[47] One scholar has suggested that "Abad y Queipo is best regarded as the intellectual progenitor of Mexican Liberalism."[48]

Insurgency for independence and agrarian violence 1810–21

The outbreak of the insurgency in September 1810 led by secular cleric Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla was joined by Indians and castas in huge numbers in the commercial agricultural region of the Bajío. The Bajío did not have an established sedentary indigenous population prior to the arrival of the Spaniards even though the area had fertile soils. Once the Spanish defeated fierce northern indigenous from the region, Spaniards created towns and commercial agricultural enterprises that were cultivated by workers who had no rights to land via indigenous communities. Workers were dependent on the haciendas for employment and sustenance.[49] When Hidalgo denounced bad government to his parishioners during the Cry of Dolores, he quickly gained a following, which then expanded to tens of thousands.[50]

The Spanish crown had not seen such a challenge from below during its nearly 300 years of colonial rule. Most rural protests were brief, had local grievances, and were resolved quickly often in the colonial courts.[51] Hidalgo's political call for a rising against bad government during the period when Napoleon's forces controlled the Iberian peninsula and Spain's Bourbon monarch had been forced to abdicate in favor of Joseph Bonaparte meant that there was a crisis of authority and legitimacy in the Spanish empire, touching off the Spanish American wars of independence.

Until Hidalgo's revolt, there had been no large mobilization in New Spain. It has been argued that the perception that the ruling elites were divided in 1810, embodied in the authority figure of a Spanish priest denouncing bad government, gave the masses in the Bajío the idea that violent rebellion might succeed in changing their circumstances for the better.[52] Those following Hidalgo's call went from town to town in the Bajío, looting and sacking haciendas in their path. Hacendados did not resist, but watched the destruction unfold, since they had no means to effectively suppress it. Hidalgo had hoped to gain the support of creole elites for the cause of independence and he tried to prevent attacks on haciendas owned by potential supporters, but the mob made no distinction between Iberian-born Spaniards’ estates and those of American-born Spaniards. Any support those creole estate owners might have for independence disappeared as the mob destroyed their property. Although for the largely landless peasants of the Bajío inequality of land ownership fueled their violence, Hidalgo himself did not have an economic program of land reform. Only after Hidalgo's defeat on the march to Mexico City did he issue a proclamation to return lands rented by villages to their residents.[53]

Hidalgo appealed to indigenous communities in central Mexico to join his movement, but they did not. It is argued that the crown's protection of indigenous communities’ rights and lands made them loyal to the regime and that the symbiotic relationship between indigenous communities and haciendas created a strong economic incentive to preserve the existing relationships. In central Mexico, loss of land was incremental so that there was no perception that the crown or the haciendas were the agents of the difficulties of the indigenous.[54] Although the Hidalgo revolt showed the extent of mass discontent among some rural populations, it was a short-lived regional revolt that did not expand beyond the Bajío.

More successful in demonstrating that agrarian violence could achieve gains for peasants was the guerrilla warfare that continued after the failure of the Hidalgo revolt and the execution of its leaders. Rather than a massed group of men attempting to achieve a quick and decisive victory pitted against the small but effective royal army, guerrilla warfare waged over time undermined the security and stability of the colonial regime.[55] The survival of guerrilla movements was dependent on support from surrounding villages and the continuing violence undermined the local economies, however, they did not formulate an ideology of agrarian reform.

Hidalgo did not formulate a program of land reform, although the inequality of land ownership was at the core of the Bajío peasants’ economic situation. The political plan of secular priest José María Morelos likewise did not revolve around land reform, nor did the Plan de Iguala of Agustín de Iturbide. But the alliance that former royalist officer Iturbide with guerrilla leader Vicente Guerrero to create the Army of the Three Guarantees that bought about Mexican independence in September 1821 is rooted in the political force that agrarian guerrillas exerted. The agrarian violence of the independence era was the start of more than a century of peasant struggle.

Post-independence era, 1821–1910

Armed peasant struggle to regain land

As a response to the loss of land, a number of indigenous communities sought to regain land through rebellion in post-independence Mexico. In the nineteenth century, the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, central Mexico, Yucatan, and the northwest regions of the Yaqui and Mayo saw serious rebellions. The Caste War of Yucatan and the Yaqui Wars were lengthy conflicts, lasting into the twentieth century. During the Mexican Revolution, many peasants fought for the return of community lands, most notably in Morelos under the leadership of Emiliano Zapata. Armed struggle or its threat were key to the post-revolutionary Mexican government's approach to land reform. Land reform "helped to stifle peasant revolts, succeeded in modifying land tenure relationships, and was of paramount importance in the institutionalization of the new regime."[56]

Liberal reform and the 1856 Lerdo Law

In the years previous to the Reform War, a series of reforms were instituted by the liberals who came to power following the ouster of Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1854 and were aimed at restructuring the country under liberal principles. These laws were known as Reform Laws (known in Spanish as Leyes de Reforma). One of these laws dealt with all concepts related to land tenure and was named after the Finance Minister, Miguel Lerdo de Tejada.

The Lerdo Law (known in Spanish as Ley Lerdo) empowered the Mexican state to force the sale of corporately held property, specifically those of the Roman Catholic Church in Mexico and the lands held by indigenous communities. The Lerdo Law did not directly expropriate ecclesiastical property or peasant communities but were to be sold to those renting the properties and the price to be amortized over 20 years. Properties not being rented or claimed could be auctioned. The church and indigenous communities were to receive the proceeds of the sale and the state would receive a transaction tax payment.[57] Not all church land was confiscated; however, land not used for specific religious purposes was sold to private individuals.[58]

This law changed the nature of land ownership allowing more individuals to own land, rather than institutions.

One of the aims of the reform government was to develop the economy by returning to productive cultivation the underutilized lands of the Church and the municipal communities (Indian commons), which required the distribution of these lands to small owners. This was to be accomplished through the provisions of Ley Lerdo that prohibited ownership of land by the Church and the municipalities.[59] The reform government also financed its war effort by seizing and selling church property and other large estates.

The aim of the Lerdo Law with Indian corporate land was to transform Indian peasants pursuing subsistence agriculture into Mexican yeoman farmers. This did not happen. Most Indian land was acquired by large estates, which had the means to purchase it and made Indians even further dependent on landed estates.[60]

Porfiriato - Land expropriation and foreign ownership (1876-1910)

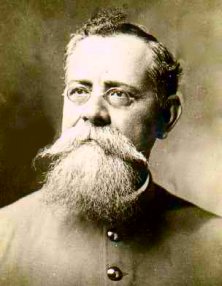

During the presidency of liberal general Porfirio Díaz, the regime embarked on a sweeping project of modernization, inviting foreign entrepreneurs to invest in Mexican mining, agriculture, industry, and infrastructure. The laws of the Liberal Reform established the basis for extinguishing corporate ownership of land by the Roman Catholic Church and indigenous communities. The liberal regime under Díaz vastly expanded the state's role in land policy by mandating that so-called "unoccupied lands" (terrenos baldíos) be surveyed and opened to development by Mexicans and foreign individuals and corporate entities. The government hired private survey companies for all land not previously surveyed so that land could then be sold, while the company would retain one-third of the land its surveyed. The surveys were intended to give buyers security of title to the land they bought and was a tool in encouraging investment. For Mexicans who could not prove title to land or had informal usufruct rights to pastures and woodlands, the surveys put an end to such common usage and put land into private hands. The regime's aim was that the land would then become more efficiently used and productive.[61][62]

There were many absentee investors from the U.S. who were involved in finance or other business enterprises, including William Randolph Hearst and wheat magnate William Wallace Cargill, who bought land from survey companies or from private Mexican estate owners. Díaz loyalists, such Matías Romero, José Yves Limantour, and Manuel Romero Rubio, as well as the Díaz family took advantage of the opportunities to increase their wealth by acquiring large tracts of land. Investors in productive land further increased its value by their proximity to railway lines that linked properties to regional and international markets. Some entrepreneurs built spur railway lines to connect with the trunk lines.[63] U.S. investors acquired land along the Mexico's northern border, especially Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Tamaulipas, but also on both coasts as well as the Isthmus of Tehuantepec.[64]

The situation of landless Mexicans became increasingly worse, so that by the end of the Porfiriato, virtually all (95%) of villages lost their lands.[65][66] In Morelos, the expansion of sugar plantations triggered peasant protests against the Díaz regime and were a major factor in the outbreak and outcomes of the Mexican Revolution. There was resistance in Michoacán.[67]

Land loss accelerated for small holders during the Porfiriato[68] as well as indigenous communities.[69] Small holders were further disadvantaged in that they could not get bank loans for their enterprises since the amounts were not worth the expense to the bank of assessing the property.[70] Molina Enríquez's work published just prior to the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution had a tremendous impact on the legal framework on land tenure that was codified in Article 27 of the Mexican Constitution of 1917. Peasant mobilization during the Revolution brought about state-directed land reform, but the intellectual and legal framework for how it was accomplished is extremely important.

Calls for land reform

In 1906, the Liberal Party of Mexico wrote a program of specific demands, many of which were incorporated into the Constitution of 1917. Leftist Ricardo Flores Magón was president of the PLM and his brother Enrique Flores Magón was treasurer. Two demands that were adopted were (Point 34) that landowners needed to make their land productive or risk confiscation by the state. (Point 35) demands that "The Government will grant land to anyone who solicits it, without any conditions other than that the land be used for agricultural production and not be sold. The maximum amount of land that the Government may allot to one person will be fixed."[71]

A key influence on agrarian land reform in revolutionary Mexico was of Andrés Molina Enríquez, who is considered the intellectual father of Article 27 of the 1917 Constitution. His 1909 book, Los Grandes Problemas Nacionales (The Great National Problems) laid out his analysis of Mexico's unequal land tenure system and his vision of land reform.[72] On his mother's side Molina Enríquez had come from a prominent, politically well-connected, land-owning family, but his father's side was from a far more modest background and he himself had modest circumstances. For nine years in the late 19th century, Molina Enríquez was a notary in Mexico State, where he observed first-hand how the legal system in Porfirian Mexico was slanted in favor of large estate owners, as he dealt with large estate owners (hacendados), small holders (rancheros), and peasants who were buying, transferring, or titling land.[73] In his observations, it was not the large estates or the subsistence peasants that produced the largest amount of maize in the region, but rather the rancheros; he considered the hacendado group "inherently evil".[74] In his views on the need for land reform in Mexico, he advocated for the increase in the ranchero group.[75]

In The Great National Problems, Molina Enríquez concluded that the Porfirio Díaz regime had promoted the growth of large haciendas although they were not as productive as small holdings. Citing his nearly decade long tenure as a notary, his claims were well-founded that haciendas were vastly under-assessed for tax purposes and that small holders were disadvantaged against the wealth and political connections of large estate owners. Since title transfers of property required payment of fees and that the fee was high enough to negatively affect small holders but not large. In addition, the local tax on title transfers was based on a property's assessment, so in a similar fashion, small holders paid a higher percentage than large holders who had ample means to pay such taxes.[76] Large estates often occupied more land than they actually held title to, counting on their size and clout to survive challenges by those on whom they infringed.[77] A great number of individual small holders had only imperfect title to their land, some no title at all, so that Díaz's requirement that land be properly titled or be subject to appropriation under the "vacant lands" law (terrenos baldíos) meant that they were at risk for losing their land. Indian pueblos also lost their land, but the two processes of land loss were not one and the same.[78]

Land reform, 1911-1946

The Mexican Revolution reversed the Porfirian trend towards land concentration and set in motion a long process of agrarian mobilization that the post-revolutionary state sought to control and prevent further major peasant uprisings. The power and legitimacy of the traditional landlord class, which had underpinned Porfirian rule, never recovered. The radical and egalitarian sentiments produced by the revolution had made landlord rule of the old kind impossible, but the Mexican state moved to stifle peasant mobilization and the recreation of indigenous community power.

Revolutionary peasant movements

During the Mexican Revolution, two leaders stand out as carrying out immediate land reform without formal state intervention, Emiliano Zapata in the state of Morelos and Pancho Villa in northern Mexico. Although the political program of wealthy northern landowner Francisco I. Madero, the Plan of San Luis Potosí, promised the return of village lands unlawfully confiscated by large estate owners, when the Díaz regime fell and Madero was elected president of Mexico, he took little action on land reform. Zapata led peasants in the central state of Morelos, who divided up large sugar haciendas into plots for subsistence agriculture; in northern Mexico, Zapata and others in Morelos drafted the Plan of Ayala, which called for land reform and put the region in rebellion against the government. Unlike many other revolutionary plans, Zapata's was actually implemented, with villagers in areas under his forces control regaining village lands, but also seizing lands of sugar plantations and dividing them. The seizing of sugar plantations and distribution to peasants for small-scale cultivation was the only significant land reform during the Revolution.[79] They remained in opposition to the government in its subsequent forms under reactionary general Victoriano Huerta and then Constitutionalist leader Venustiano Carranza. Peasants sought land of their own to pursue subsistence agriculture, not the continuation of commercial sugar cultivation. Although Carranza's government after 1915 fought a bloody war against Zapatista forces and Zapata was assassinated by an agent of Carranza's in 1919, land reform there could not be reversed. When Alvaro Obregón became president in 1920, he recognized the land reform in Morelos and Zapatistas were given control of Morelos.[80]

The situation in northern Mexico was different from the Zapatista area of central Mexico, with few subsistence peasants, a tradition of military colonies to fight indigenous groups such as the Apaches, the development of large cattle haciendas and small ranchos. During the Porfiriato, the central Mexican state gained more control over the region, and hacienda owners who had previously not encroached on small holders' lands or limited access to large expanses of public lands began consolidating their holdings at the expense of small holders. The Mexican government contracted with private companies to survey the "empty lands," (tierras baldíos) and those companies gained a third of all land they surveyed. The rest of these lands were bought by wealthy landowners. Most important was the Terrazas-Creel family, who already owned vast estates and wielded tremendous political and economic power. Under their influence, Chihuahua passed a law forcing military colonies to sell their lands, which they or their allies bought. The economic Panic of 1907 in the U.S. had an impact on the border state of Chihuahua, where newly unemployed miners, embittered former military colonists, and small holders joined to support Francisco I. Madero's movement to oust Díaz. Once in power, however, president Madero's promises of land reform were unfulfilled causing disgruntled former supporters to rebel. In 1913 after Madero's assassination, Pancho Villa joined the movement to oust Victoriano Huerta and under his military leadership, Chihuahua came under his control. As governor of the state, Villa issued decrees that placed large estates under the control of the state. They continued to be operated as haciendas with the revenues used to finance the revolutionary military and support widows and orphans of Villa's soldiers. Armed men fighting with Villa saw one of their rewards as being access to land, but Villa expected them to fight far outside where they currently lived, unlike the men following Zapata, who fought where they lived and had little incentive to fight elsewhere. Villa's men would be rewarded following the Revolution. Villa issued a decree declaring that nationally all estates above a certain size would be divided among peasants, with owners to be given some compensation. Northerners sought more than a small plot of land for subsistence agriculture, but rather a parcel large enough to be designated a rancho on which they could cultivate and/or ranch cattle independently. Although Villa was defeated by Venustiano Carranza's best general, Alvaro Obregón, in 1915 and his sweeping land reform could not be implemented, the Terrazas-Creel's properties were not returned to them following the Revolution.[81]

Land reform under Carranza, 1915-1920

Land reform was an important issue in the Mexican Revolution, but the leader of the winning faction, wealthy landowner Venustiano Carranza was disinclined to pursue land reform. But in 1914 the two important Constitutionalist generals, Alvaro Obregón and Pancho Villa, called on him to articulate a policy of land distribution.[82] One of Carranza's principal aides, Luis Cabrera, the law partner of Andrés Molina Enríquez, drafted the Agrarian Decree of January 6, 1915, promising to provide land for those in need of it.[82] The driving idea behind the law was to blunt the appeal of Zapatismo and to give peasants access to land to supplement income during periods when they were not employed as day laborers on large haciendas and fought against the Constitutionalists. Central to their notion was the re-emergence of the ejido, lands traditionally under control of communities. Cabrera became the point person for Carranza's agrarian policy, pitching the proposal as a military necessity, as a way to pacify communities in rebellion. "The mere announcement that the government is going to proceed to the study of the reconstitution of the ejidos will result in the concentration of people in the villages, and it will facilitate, therefore the domination of the region."[83] With the defeat of Victoriano Huerta, the Constitutionalist faction split, with Villa and Zapata, who advocated more radical agrarian policies, opposing Carranza and Obregón. In order to defeat them both militarily and on the social and political fronts, Carranza had to counter their appeal to the peasantry. Constitutionalist military units expropriated some haciendas to award the lands to villages potentially supporting more radical solutions, but the Agrarian Decree did not call for wholesale expropriations. Although the lands expropriated were called ejidos, they were not structured as restitution to villages, but as new grants conferred by the state, often of poor quality and smaller than what villages previously held. Carranza's government set up a bureaucracy to deal with land reform, which in practice sought to limit implementation of any sweeping changes favorable to the peasantry. Many landlords whose estates had been expropriated were restored to them during the Carranza era. Villages that were to receive grants had to agree to pay the government for the land. The colonial-era documentation for villages' land claims were deemed invalid. As the Carranza presidency ended in 1920, the government was asserting power to prevent serious land reform or any peasant control over its course.[84] Carranza had only supported limited land reform as a strategy, but once in power, he assured estate owners that their land would be returned to them. Although his resistance to land reform prevented its implementation, he could not block the adoption of article 27 of the revolutionary constitution of 1917 that recognized villages' rights to land and the power of the state over subsoil rights.[85]

Under Obregón, 1920-1924

Wealthy landowner and brilliant general of the Revolution, Alvaro Obregón came to power in a coup against Carranza. Since the Zapatistas had supported his bid for power, he placated them by ending attempts to recover seized land and return them to big sugar estate owners. However, his plan was to make the peasantry there dependent on the Mexican state and viewed agrarian reform as a way to strengthen the revolutionary state.[86] During his presidency, Mexico it was clear that some land reform needed to be carried out. Agrarian reform was a revolutionary goal for land redistribution as part of a process of nationalization and "Mexicanization". Land distribution began almost immediately and affected both foreign and large domestic land owners (hacendados). The process was deliberately very slow, since generally Obregón did not consider it a top priority. However, in order to maintain the social peace with the peasantry, he began land reform in earnest. As president, Obregón distributed 1.7 million hectares, which was 1.3Ò% of agricultural land.[87] The land distributed was mostly not existing cultivated lands, consisting of forests, pastures, mountainous land, and other uncultivable land (ranging from 51%-64.6%). Rain-fed land was the next largest category (ranging from 31.2% to 41.4%). The smallest amount of land distributed was irrigable land, ranging from a high of 8.2% in 1920 to just 4.2% in 1924.[88] When Obregón sought to ensure his fellow Sonoran revolutionary general Plutarco Elías Calles was his successor, Obregón and Calles promised land reform to mobilize peasants against their rival Adolfo de la Huerta. Their faction prevailed and when Calles became president in 1924, he did increase distribution of land.[89]

Calles and the Maximato, 1924-1934

Plutarco Elías Calles was the successor to Obregón in the election of 1924 and when Obregón assassinated in 1928 after being re-elected president Calles remained in power 1928-1934 as the jefe máximo (maximum chief) in a period known as the Maximato. Along with fellow Sonoran Obregón, Calles was not an advocate of land reform, and sought to create a vital industrial sector in Mexico. In general, Calles blocked measures for land reform and sided with landlords. During his presidency, the U.S. government was opposed to land reform in Mexico, since some of its citizens owned land and petroleum enterprises there. Although ejidos had been created under Obregón's presidency, Calles envisioned them being turned into private holdings. Calles's administration did seek to expand the agricultural sector by colonizing areas not previously cultivated or existing lands that were deemed inefficiently used. Extending credit to agricultural enterprises benefited large land owners rather than the peasantry. State-constructed Irrigation projects to increase production likewise benefited them. Since many revolutionary leaders, including Obregón and Calles, were recipients of large tracts of land, they were direct beneficiaries of state-directed agricultural infrastructure and credit. During Calles's presidency (1924–28), 3.2 million hectares of agricultural land were distributed, 2.4% of all agricultural land.[90] The largest category of land distributed was non-agricultural land ranging from forests, pastures, mountainous, and other uncultivable lands, ranging from 60% to nearly 80% in 1928. Rainfed land was the next largest category, ranging from 35% to 20%. The smallest amount was irrigable land, just 3-4%.[91]

Cardenista land reform 1934 to 1940

President Lázaro Cárdenas is credited with revitalizing land reform, along with other measures in keeping with the rhetoric of the Revolution. Although he was from the southern state of Michoacan, Cárdenas was part of the northern Constitutionalist revolutionary forces that emerged victorious during the Revolution. He did not join with the forces of Emiliano Zapata or Pancho Villa, who advocated sweeping land reform. Cárdenas distributed most land between 1936 and 1938, after he had ousted Calles and took full control of the government and before his expropriation of foreign oil companies in 1938. He was determined to distribute land to the peasantry, but also keep control of the process rather than have peasants seize land. His most prominent expropriation of land was in the Comarca Lagunera, with rich, irrigated soil. Some 448,000 hectares of land there were expropriated in 1936, of which 150,000 were irrigated. he directed similar expropriations in Yucatán and the Yaqui valley in 1937; Lombardía and Nueva Italia, Michoacan; Los Mochis, Sinaloa; and Soconusco Chiapas in 1938. Rather than dividing land into individual ejidos, which peasants preferred and on which they pursued subsistence agriculture, Cárdenas created collective ejidos. Communities were awarded land but they were worked as a single unit. This was done for lands producing commercial crops such as cotton, wheat, henequen, rice, sugar, citrus, and cattle, so that they would continue to be commercially viable for the domestic and export markets. Collective ejidos received more government support than individual ejidos.[92]

Agrarian reform had come close to extinction in the early 1930s during the Maximato, since Calles was increasingly hostile to it as a revolutionary program. The first few years of the Cárdenas's reform were marked by high food prices, falling wages, high inflation, and low agricultural yields.[93] In 1935 land reform began sweeping across the country in the periphery and core of commercial agriculture.[94] The Cárdenas alliance with peasant groups has been credited with the destruction of the hacienda system. Cárdenas distributed more land than all his revolutionary predecessors put together, a 400% increase. Cárdenas wanted the peasantry tied to the Mexican state and did so by organizing peasant leagues that collectively represented the peasantry, the National Confederation of Peasants (CNC), within the new, sectoral party structure that Cárdenas created within the Party of the Mexican Revolution.[95]

During his administration, he redistributed 45,000,000 acres (180,000 km2) of land, 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) of which were expropriated from U.S. nationals who owned agricultural property.[96] This caused conflict between Mexico and the United States. Cárdenas employed tactics of noncompliance and deception to gain leverage in this international dispute.[96]

End of land reform, 1940-present

Starting the government of Miguel Alemán (1946–52), land reform steps made in previous governments were rolled back. Alemán's government allowed entrepreneurs to rent peasant land. This created phenomenon known as "neolatifundismo," where land owners build up large-scale private farms on the basis of controlling land which remains ejidal but is not cultivated by the peasants to whom it is assigned.

Echeverría's populist land reform

In 1970, President Luis Echeverría began his term by declaring land reform dead. In the face of peasant revolt, he was forced to backtrack, and embarked on the biggest land reform program since Cárdenas. Echeverría legalized take-overs of huge foreign-owned private farms, which were turned into new collective ejidos.

Land reform from 1991 to present

In 1988, President Carlos Salinas de Gortari was elected. In December 1991, he amended Article 27 of the Constitution, making it legal to sell ejido land and allow peasants to put up their land as collateral for a loan. Neverthess, land regulation is still permitted in Mexico by Article 27.[97]

See also

- Index of Mexico-related articles

- Economic history of Mexico

- Ejido

- Mexican Revolution

- Foreign relations of Mexico

References

- ^ Markiewicz, Dana, The Mexican Revolution and the Limits of Agrarian Reform, 1915-1946. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers 1993.

- ^ Hart, John Mason, Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War. Berkeley: University of California Press 2002

- ^ Dwyer, Johnre J. The Agrarian Dispute: The Expropriation of American-Owned Rural Land in Postrevolutionary Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 2008.

- ^ Cumberland, Charles. The Meaning of the Mexican Revolution(US: D. C. Health and Company, 1967), 41

- ^ Carleton Beals, Mexico an Interpretation(New York: B.W.Huebsch Inc., 1923), 89

- ^ Carleton Beals, Mexico an Interpretation(New York: B.W.Huebsch Inc., 1923), 92

- ^ Malcolm Dunn, "Privatization, Land Reform, and Property Rights: The Mexican Experience," Constitutional Political Economy, 11(2000):217

- ^ Grohmann, Horacio Mackinlay (1993). "Las reformas de 1992 a la legislación agraria. El fin de la Reforma Agraeia mexicana y la privatización del ejido". Polis (in Spanish). 1 (1): 99–130. ISSN 2594-0686.

- ^ Charles Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1964, pp. 257ff.

- ^ Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule, p.257

- ^ S.L. Cline, ‘’Colonial Culhuacan, 1580-1600: A Social History of an Aztec Town’’. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1986, pp. 140-141.

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: The General History of the Things of New Spain, volume 8, p. 88. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- ^ Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex The General History of the Things of New Spain, edited and translated by Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, volume 11, p.251. This civil category of land is part of the compilation on soil types.

- ^ Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, Obras Históricas, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de México, 1977, vol. 2, p. 385.

- ^ S.L. Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, 1580 – 1600: A Social History of an Aztec Town. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1986, pp. 125-159., S.L. Cline and Miguel León-Portilla, The Testaments of Culhuacan. Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center, Nahuatl Studies Series No. 1, 1984.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-06-22. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Charles Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1964.

- ^ Alonso de Zorita, Life and Labor in Ancient Mexico, translated by Benjamin Keen. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press 1963.

- ^ Georges Baudot, Utopie et histoire au Mexique. Paris: Privat 1976:45ff.

- ^ Zorita, Life and Labor, p. 86.

- ^ Cline, Colonial Culhuacan p. 141.

- ^ Cline, Howard F. (1966). "The Oztoticpac Lands Map of Texcoco 1540". The Quarterly Journal of the Library of Congress. 23 (2): 76–115. ISSN 0041-7939.

- ^ James Lockhart, "Encomienda and Hacienda: The Evolution of the Great Estate in the Spanish Indies," Hispanic American Historical Review 59 (August 1969).

- ^ Ida Altman, Sarah Cline, and Javier Pescador, The Early History of Greater Mexico. Pearson 2003.

- ^ Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, pp. 155-57, based on land sales records for late 16th-century Culhuacan.

- ^ Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, p. 155.

- ^ A vara = 0.84 meters. Cline, Colonial Culhuacan, p. 129

- ^ Woodrow W. Borah, Justice By Insurance: The General Indian Court of Colonial Mexico and the Legal Aides of the Half-Real. University of California Press 1983, p. 136.

- ^ Wood, Stephanie, "The Fundo Legal or lands Por Razón de Pueblo: New Evidence from Central New Spain." In The Indian Community of Colonial Mexico: Fifteen Essays on Land Tenure, Corporate Organization, Ideology and Village Politics. Arij Ouweneel and Simon Miller, eds. pp. 117-29. Amsterdam: CEDLA 1990.

- ^ Gibson, The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule

- ^ Emilio H. Kourí, "Interpreting the Expropriation of Indian Pueblo Lands in Porfirian Mexico," Hispanic American Historical Review 82:1, 2002, pp. 79-80

- ^ Kouri, "Interpreting", pp. 79-80.

- ^ Borah, Justice by Insurance, p. 122.

- ^ Borah, Justice by Insurance, p. 123

- ^ Borah, Justice by Insurance, p. 138-39.

- ^ Borah, Justice by Insurance, p. 140.

- ^ John Tutino, "Agrarian Policy: 1821 – 1876," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1. p. 7.

- ^ D.A. Brading, The First America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991, pp. 510-12.

- ^ John H.R. Polt, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos. New York: Twayne Publishers 1971.

- ^ Brading, The First America, p. XX

- ^ a b Brading, The First America, p. 568.

- ^ Herman W. Konrad, A Jesuit Hacienda in Mexico: Santa Lucía 1576-1767. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1980.

- ^ Charles H. Harris III, The Sánchez Navarros: a socio-economic study of a Coahuilan latifundio, 1846-1853. Chicago: Loyola University Press 1964.

- ^ Brading, The First America, p. 569.

- ^ Brading, The First America, p. 369.

- ^ Brading, The First America, p. 370.

- ^ Abad y Queipo quoted in Brading, The First America p. 370

- ^ Brading, The First America, p. 573.

- ^ John Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution in Mexico: Social Bases of Agrarian Violence, 1750-1940. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1986, pp. 55-56.

- ^ Hugh Hamill, The Hidalgo Revolt. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1966.

- ^ William B. Taylor, Drinking, Homicide, and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1979.

- ^ Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution p. 100.

- ^ Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution, p. 151.

- ^ Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution pp. 178-182.

- ^ Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution, p. 183

- ^ Markiewicz, Dana. The Mexican Revolution and the Limits of Agrarian Reform, 1915-1946. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers 1993, p.2.

- ^ Tutino, From Insurrection to Revolution, p. 260.

- ^ Lee Stacy, Mexico and the United States,(New York: Marshall Cavendish, 2002) 699

- ^ Jaime Suchlicki, Mexico: From Montezuma to the Fall of the PRI, Brassey's (2001), ISBN 1-57488-326-7, ISBN 978-1-57488-326-8

- ^ John A. Britton, "Liberalism," in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, p. 739.

- ^ Hart, Empire and Revolution, pp. 167-68.

- ^ Holden, R.H. Mexico and the Survey of Public Lands: The Management of Modernization, 1876 - 1911. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press 1993.

- ^ Hart, Empire and Revolution, pp. 167-230

- ^ Dwyer, The Agrarian Dispute, 17-19

- ^ Katz,Friedrich "Labor Conditions on Haciendas in Porfirian Mexico: Some Trends and Tendencies," Hispanic American Historical Review, 1974, 54(1), p.1.

- ^ Kourí, Emilio H. "Interpreting the expropriation of Indian pueblo lands in Porfirian Mexico: The unexamined legacies of Andrés Molina Enríquez," Hispanic American Historical Review 82:1, 70.

- ^ Jennie Purnell, "'With all due respect': Popular resistance to the privatization of communal lands in nineteenth-century Michoacán," Latin American Research Review 34, no. 1 1999.

- ^ Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez, p. 20.

- ^ Kourí, "Interpreting the Expropriation of Indian Pueblo Lands," p. 73.

- ^ Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez, p. 19. The problem persists in the developing world and in recent years the establishment of microfinance non-governmental organizations has begun aiding those too poor for ordinary financial institutions.

- ^ "Liberal Party Program, 1906" reprinted from James D. Cockcroft, Intellectual Precursors of the Mexican Revolution, Austin: University of Texas Press 1968 in Mexico: From Independence to Revolution: 1810-1910, edited by W. Dirk Raat. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1982, p. 276.

- ^ Stanley F. Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez: Mexican Land Reformer of the Revolutionary Era. Tucson: University of Arizona Press 1994.

- ^ Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez, p. 15.

- ^ Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez, p. 11.

- ^ Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez, p. 16.

- ^ Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez, pp. 18-19.

- ^ Shadle, Andrés Molina Enríquez, p. 19.

- ^ Kourí, "Interpreting the Expropriation of Indian Pueblo Lands," p. 73.

- ^ Katz, Friedrich, "The Agrarian Policies and Ideas of the Revolutionary Factions Led by Emiliano Zapata, Pancho Villa, and Venustiano Carranza" in Laura Randall, ed. Reforming Mexico's Agrarian Reform. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe Publishers, 1996, p. 21.

- ^ Katz, "Agrarian Policies," p. 23-24.

- ^ Katz, "Agrarian Policies and Ideas" pp. 27-33.

- ^ a b Linda Hall, "Alvaro Obregon and the Politics of Mexican Land Reform, 1920-1924,"Hispanic American Historical Review 60:2 (May 1980):213

- ^ quoted in Markiewicz The Mexican Revolution, p. 25.

- ^ Markiewicz, The Mexican Revolution, pp. 26-33.

- ^ Tutino, John. The Mexican Heartland. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2018, pp. 314-15

- ^ Tutino, Mexican Heartland, p. 325.

- ^ Markiewicz, The Mexican Revolution, Table 6, Land Distributed as a Percentage of All Agricultural Land by Presidential Period", p. 184.

- ^ Markiewicz, The Mexican Revolution, Table 5. "Quality of Land Awarded.", p. 183.

- ^ Tutino, The Mexican Heartland, p. 326.

- ^ Markiewicz, The Mexican Revolution, Table 6, "Land Distributed as a Percentage of Agricultural Land", p. 184

- ^ Markiewicz, The Mexican Revolution, Table 5, Quality of Land, p. 183.

- ^ Markiewicz, The Mexican Revolution, pp. 95-97.

- ^ Dwyer, John. "Diplomatic Weapons of the Weak: Mexican Policymaking during the U.S.-Mexican Agrarian Dispute, 1934-1941,Diplomatic History, 26:3 (2002): 379

- ^ Héctor Camin, Lorenzo Meyer, & Luis Fierro, In the Shadow of the Mexican Revolution: Contemporary Mexican History, 1910-1989,(Austin: University of Texas, 1993), 132

- ^ Stanford, Lois. "Confederación Nacional Campesina (CNC)", in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, p. 286. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997

- ^ a b John Dwyer, "Diplomatic Weapons of the Weak: Mexican Policymaking during the U.S.-Mexican Agrarian Dispute, 1934-1941,Diplomatic History, 26:3 (2002): 375

- ^ "Mexican Constitution, Articles 3, 27, 123 and 130". Mexico History Documents. 2005. Retrieved December 22, 2020.

Further reading

- Albertus, Michael, et al. "Authoritarian survival and poverty traps: Land reform in Mexico." World Development 77 (2016): 154–170.

- Bazant, Jan. The Alienation of Church Wealth in Mexico. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press 1971.

- De Janvry, Alain, and Lynn Ground. "Types and consequences of land reform in Latin America." Latin American Perspectives 5.4 (1978): 90–112.

- Dwyer, John J. The Agrarian Dispute: The Expropriation of American-Owned Land in Postrevolutionary Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 2008.

- Hart, John Mason. Empire and Revolution: The Americans in Mexico since the Civil War. Berkeley: University of California Press 2002.

- Harvey, Neil. Rebellion in Chiapas: Rural Reforms, Campesino Radicalism and the Limits of Salinismo. La Jolla: University of California, San Diego 1994.

- Heath, John Richard. Enhancing the contribution of land reform to Mexican agricultural development. Vol. 285. World Bank Publications, 1990.

- Historia de la cuestión agraria mexicana. 9 vols. Mexico City: Siglo XXI, 1988.

- Holden, R.H. Mexico and the Survey of Public Lands: The Management of Modernization, 1876 - 1911. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press 1993.

- Katz, Friedrich. "Mexico: Restored Republic and Porfiriato, 1867 - 1910," in The Cambridge History of Latin America: vol. 5, edited by Leslie Bethell. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press 1986.

- Katz, Friedrich, ed. Riot, Rebellion, and Revolution: Rural Conflict in Mexico. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1988.

- Knight, Alan. ""Cardenismo: Juggernaut or Jalopy?" Journal of Latin American Studies. Vol. 26, No. 1 (Feb. 1994)

- Kroeber, Clifton B. Man, Land, and Water: Mexico's Farmlands Irrigation Policies, 1885 - 1911. Berkeley: University of California Press 1983.

- Lira, Andrés, Comunidades indígenas frente a la Ciudad de México. Zamora: El Colegio de Michoacán, 1983.

- Markiewicz, Dana. The Mexican Revolution and the Limits of Agrarian Reform. Boulder: Lynne Rienner 1993.

- McBride, George The Land Systems of Mexico. New York: The American Geographical Society 1923.

- Mejía Fernández, Miguel. Política agraria en México en el siglo XIX. Mexico City: Siglo XXI 1979.

- Miller, Simon. Landlords and Haciendas in Modernizing Mexico. Amsterdam: CEDLA 1995.

- Phipps, Helen. "Some aspects of the agrarian question in Mexico: A historical study," University of Texas Bulletin 2515, 1925.

- Powell, T.G. El liberalismo y el campesinado en el centro de México, 1850 - 1876. Mexico City: Secretaría de Educación Pública 1974.

- Pulido Rull, Ana. Mapping Indigenous Land: Native Land Grants in Colonial New Spain. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 2020. ISBN 978-0-8061-6496-0

- Randall, Laura, ed. Reforming Mexico's Agrarian Reform. Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe 1996.

- Sanderson, Susan Walsh. Land Reform in Mexico, 1910 - 1980. Orlando FL: Academic Press 1984.

- Silva Herzog, Jesús. El agrarismo mexicano y la reforma agraria: exposición y critica. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1959. 2nd. edition 1964.

- Simpson, Eyler Newton. The Ejido: Mexico's Way Out. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1937.

- Stevens, D.F. "Agrarian Policy and Instability in Porfirian Mexico," The Americas 39:2(1982).

- Tannenbaum, Frank. The Mexican Agrarian Revolution, New York: MacMillan 1929.

- Tutino, John. From Insurrection to Revolution in Mexico. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1986.

- Tutino, John. The Mexican Heartland: How Communities Shaped Capitalism, a Nation, and World History, 1500-2000. Princeton: Princeton University Press 2018.

- Wasserman, Mark. Capitalists, Caciques, and Revolution: the Native Elite and Foreign Enterprise in Chihuahua, Mexico 1854 - 1911. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1984.

- Whetten, Nathan. Rural Mexico. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1948.

- Wolfe, Mikael D. Watering the Revolution: An Environmental and Technological History of Agrarian Reform in Mexico. Durham: Duke University Press 2017.

- Wood, Stephanie, "The Fundo Legal or lands Por Razón de Pueblo: New Evidence from Central New Spain." In The Indian Community of Colonial Mexico: Fifteen Essays on Land Tenure, Corporate Organization, Ideology and Village Politics. Arij Ouweneel and Simon Miller, eds. pp. 117–29. Amsterdam: CEDLA 1990