Afsharid Iran

Guarded Domains of Iran | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1736–1796 | |||||||||||||||||||||

The Afsharid Empire at its greatest extent in 1741–1745 under Nader Shah | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mashhad | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Shahanshah | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1736–1747 | Nader Shah | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1747–1748 | Adel Shah | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1748 | Ebrahim Afshar | ||||||||||||||||||||

• 1748–1796 | Shahrokh Shah | ||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 22 January 1736 | ||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1796 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||

• 1736-1747 After 1747 estimate | 9,000,000[5] 6,000,000[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Toman[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | IR | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Iran |

|---|

The Gate of All Nations in Fars |

|

Timeline |

The Guarded Domains of Iran,[8][9] commonly referred to as Afsharid Iran[a] or the Afsharid Empire,[10] was an Iranian[11] empire established by the Turkoman[12][13] Afshar tribe in Iran's north-eastern province of Khorasan, establishing the Afsharid dynasty that would rule over Iran during the mid-eighteenth century. The dynasty's founder, Nader Shah, was a successful military commander who deposed the last member of the Safavid dynasty in 1736, and proclaimed himself Shah.[14]

During Nader's reign, Iran reached its greatest extent since the Sasanian Empire. At its height it controlled modern-day Iran, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Afghanistan, Bahrain, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, and parts of Iraq, Pakistan, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Oman and the North Caucasus (Dagestan). After his death, most of his empire was divided between the Zands, Durranis, Georgians, Khanate of Kalat, and the Caucasian khanates, while Afsharid rule was confined to a small local state in Khorasan. Finally, the Afsharid dynasty was overthrown by Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar in 1796, who would establish a new native Iranian empire and restore Iranian suzerainty over several of the aforementioned regions.

The dynasty was named after the Turkoman Afshar tribe from Khorasan in north-east Iran, to which Nader belonged.[15] The Afshars had originally migrated from Turkestan to Azerbaijan (Iranian Azerbaijan) in the 13th century. In the early 17th century, Abbas the Great moved many Afshars from Azerbaijan to Khorasan to defend the north-eastern borders of his state against the Uzbeks, after which the Afshars settled in those regions. Nader belonged to the Qereqlu branch of the Afshars.[16]

Name

Since the Safavid era, Mamâlek-e Mahruse-ye Irân (Guarded Domains of Iran) was the common and official name of Iran.[8][17] The idea of the Guarded Domains illustrated a feeling of territorial and political uniformity in a society where the Persian language, culture, monarchy, and Shia Islam became integral elements of the developing national identity.[18] The concept presumably had started to form under the Mongol Ilkhanate in the late 13th-century, a period in which regional actions, trade, written culture, and partly Shia Islam, contributed to the establishment of the early modern Persianate world.[19]

History

Foundation of the dynasty

Nader Shah was born (as Nadr Qoli) into a humble semi-nomadic family from the Afshar tribe of Khorasan,[20] where he became a local warlord.[21] His path to power began when the Ghilzai Mir Mahmud Hotaki overthrew the weakened and disintegrated Safavid shah Sultan Husayn in 1722. At the same time, Ottoman and Russian forces seized Iranian land. Russia took swaths of Iran's Caucasian territories in the North Caucasus and Transcaucasia, as well as mainland northern Iran, by the Russo-Persian War, while the neighbouring Ottomans invaded from the west. By the 1724 Treaty of Constantinople, they agreed to divide the conquered areas between themselves.[22]

On the other side of the theatre, Nader joined forces with Sultan Husayn's son Tahmasp II and led the resistance against the Ghilzai Afghans, driving their leader Ashraf Khan easily out of the capital in 1729 and establishing Tahmasp on the throne. Nader fought to regain the lands lost to the Ottomans and Russians and to restore Iranian hegemony in Iran. While he was away in the east fighting the Ghilzais, Tahmasp waged a disastrous campaign in the Caucasus which allowed the Ottomans to retake most of their lost territory in the west . Nader, displeased, had Tahmasp deposed in favour of his infant son Abbas III in 1732. Four years later, after he had recaptured most of the lost Persian lands, Nader felt confident enough to have himself proclaimed shah in his own right at a ceremony on the Moghan Plain.[23]

Nader subsequently made the Russians cede the taken territories taken in 1722–23 through the Treaty of Resht of 1732 and the Treaty of Ganja of 1735.[24] Back in control of the integral northern territories, and with a new Russo-Iranian alliance against the common Ottoman enemy,[25] he continued the Ottoman–Persian War. The Ottoman armies were expelled from western Iran and the rest of the Caucasus, and the resultant 1736 Treaty of Constantinople forced the Ottomans to confirm Iranian suzerainty over the Caucasus and recognised Nader as the new Shah.[26]

Conquests of Nader Shah and the succession problem

Fall of the Hotaki dynasty

Tahmasp and the Qajar leader Fath Ali Khan (the ancestor of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar) contacted Nader and asked him to join their cause and drive the Ghilzai Afghans out of Khorasan. He agreed and thus became a figure of national importance. When Nader discovered that Fath Ali Khan was corresponding with Malek Mahmud and revealed this to the shah, Tahmasp executed him and made Nader the chief of his army instead. Nader subsequently took on the title Tahmasp Qoli (Servant of Tahmasp). In late 1726, Nader recaptured Mashhad.[27]

Nader chose not to march directly on Isfahan. First, in May 1729, he defeated the Abdali Afghans near Herat. Many of the Abdali Afghans subsequently joined his army. The new shah of the Ghilzai Afghans, Ashraf, decided to move against Nader but in September 1729, Nader defeated him at the Battle of Damghan and again decisively in November at Murchakhort, banishing the Afghans from Persian soil forever. Ashraf fled and Nader finally entered Isfahan, handing it over to Tahmasp in December and plundering the city to pay his army. Tahmasp made Nader governor over many eastern provinces, including his native Khorasan, and married him to his sister. Nader pursued and defeated Ashraf, who was murdered by his own followers.[28] In 1738, Nader Shah besieged and destroyed the last Hotaki seat of power, at Kandahar. He built a new city nearby, which he named "Naderabad".[29]

First Ottoman campaign and the regain of the Caucasus

In the spring of 1735, Nader attacked Persia's archrival, the Ottomans, and regained most of the territory lost during the recent chaos. At the same time, the Abdali Afghans rebelled and besieged Mashhad, forcing Nader to suspend his campaign and save his brother, Ebrahim. It took Nader fourteen months to crush this uprising.

Relations between Nader and the Shah had declined as the latter grew alarmed by his general's military successes. While Nader was absent in the east, Tahmasp tried to assert himself by launching a campaign to recapture Yerevan. He ended up losing all of Nader's recent gains to the Ottomans, and signed a treaty ceding Georgia and Armenia in exchange for Tabriz. Nader, furious, saw that the moment had come to depose Tahmasp. He denounced the treaty, seeking popular support for a war against the Ottomans. In Isfahan, Nader got Tahmasp drunk then showed him to the courtiers asking if a man in such a state was fit to rule. In 1732 he forced Tahmasp to abdicate in favour of the Shah's baby son, Abbas III, to whom Nader became regent.

Nader decided, as he continued the 1730–35 war, that he could win back the territory in Armenia and Georgia by seizing Ottoman Baghdad and then offering it in exchange for the lost provinces, but his plan went badly amiss when his army was routed by the Ottoman general Topal Osman Pasha near the city in 1733. Nader decided he needed to regain the initiative as soon as possible to save his position because revolts were already breaking out in Persia. He faced Topal again with a larger force and defeated and killed him. He then besieged Baghdad, as well as Ganja in the northern provinces, earning a Russian alliance against the Ottomans. Nader scored a decisive victory over a superior Ottoman force at Yeghevard (modern-day Armenia) and by the summer of 1735, Persian Armenia and Georgia were under his rule again. In March 1735, he signed a treaty with the Russians in Ganja by which the latter agreed to withdraw all of their troops from Persian territory,[30][31] those which had not been ceded back by the 1732 Treaty of Resht yet, mainly regarding Derbent, Baku, Tarki, and the surrounding lands, resulting in the reestablishment of Iranian rule over all of the Caucasus and northern mainland Iran again.

Nader becomes king

Nader suggested to his closest intimates, after a hunting party on the Moghan plains (presently split between Azerbaijan and Iran), that he should be proclaimed the new king (shah) in place of the young Abbas III.[32] The small group of close intimates, Nader's friends, included Tahmasp Khan Jalayer and Hasan-Ali Beg Bestami.[32] Following Nader's suggestion, the group did not "demur", and Hasan-Ali remained silent.[32] When Nader asked him why he remained silent, Hasan-Ali replied that the best course of action for Nader would be to assemble all the leading men of the state, in order to receive their agreement in "a signed and sealed document of consent".[32] Nader approved of the proposal, and the writers of the chancellery, which included the court historian Mirza Mehdi Khan Astarabadi, were instructed with sending out orders to the military, religious and nobility of the nation to summon at the plains.[32] The summonses for the people to attend had gone out in November 1735, and they began arriving in January 1736.[33] In the same month of January 1736, Nader held a qoroltai (a grand meeting in the tradition of Genghis Khan and Timur) on the Moghan plains. The Moghan plain was specifically chosen for its size and "abundance of fodder".[34] Everyone agreed to the proposal of Nader becoming the new king, many—if not most—enthusiastically, the rest fearing Nader's anger if they showed support for the deposed Safavids. Nader was crowned Shah of Iran on March 8, 1736, a date his astrologers had chosen as being especially propitious,[35] in attendance of an "exceptionally large assembly" composed of the military, religious and nobility of the nation, as well as the Ottoman ambassador Ali Pasha.[36]

Invasion of the Mughal Empire

In 1738, Nader Shah conquered Kandahar, the last outpost of the Hotaki dynasty and established Naderabad, Kandahar. His thoughts now turned to the Mughal Empire based in Delhi. This once powerful Muslim state to the east was falling apart as the nobles became increasingly disobedient and the Hindu Maratha Empire made inroads on its territory from the south-west. Its ruler Muhammad Shah was powerless to reverse this disintegration. Nader asked for the Afghan rebels to be handed over, but the Mughal emperor refused.

Nader used the pretext of his Afghan enemies taking refuge in India to cross the border and invade the militarily weak but still extremely wealthy far eastern empire.[37] In a brilliant campaign against the governor of Peshawar, he took a small contingent of his forces on a daunting flank march through nearly impassable mountain passes, and took the enemy forces positioned at the mouth of the Khyber Pass completely by surprise, decisively beating them despite being outnumbered two-to-one. This led to the capture of Ghazni, Kabul, Peshawar, Sindh and Lahore.

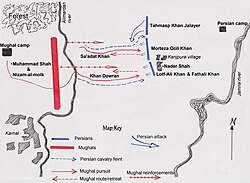

As Nader moved into the Mughal territories, he was accompanied by his loyal Georgian subject and future king of eastern Georgia, Erekle II, who led a Georgian contingent as a military commander as part of Nader's force.[38] Following the defeat of Mughal forces priorly, he then advanced deeper into India, crossing the Indus River before the end of the year. The news of the Persian army's swift and decisive successes against the northern vassal states of the Mughal empire caused much consternation in Delhi, prompting the Mughal ruler, Muhammad Shah, to summon an overwhelming force of some 300,000 men and march this massive host north towards the Persian army.

Nader Shah crushed the Mughal army in less than three hours at the large Battle of Karnal on 13 February 1739. After this decisive victory, Nader captured Mohammad Shah and entered with him into Delhi.[39] When a rumour broke out that Nader had been assassinated, some of the Indians attacked and killed Persian troops. Nader, furious, reacted by ordering his soldiers to plunder and sack the city. During the course of one day (March 22) 20,000 to 30,000 Indians were killed by the Persian troops, forcing Mohammad Shah to beg Nader for mercy.[40]

In response, Nader Shah agreed to withdraw, but Mohammad Shah paid the consequence in handing over the keys of his royal treasury, and losing even the Peacock Throne to the Persian emperor. The Peacock Throne thereafter served as a symbol of Persian imperial might. It is estimated that Nadir took away with him treasures worth as much as seven hundred million rupees. Among a trove of other fabulous jewels, Nader also gained the Koh-i-Noor and Darya-ye Noor diamonds (Koh-e-Noor means "Mountain of Light" in Persian, Darya-ye Noor means "Sea of Light").

The Persian troops left Delhi at the beginning of May 1739, but before they left, he ceded back to Muhammad Shah all territories to the east of the Indus that he had overrun.[41] Nader's soldiers also took with them thousands of elephants, horses and camels, loaded with the booty they had collected. On his return march, the Sikhs came out from the hills and ambushed Nader Shah's troops, taking some of the loot and captives with them.[42][43] However, the remaining plunder seized from India was so valuable that Nader stopped taxation in Iran for a period of three years following his return.[44] Nader attacked the empire to, perhaps, give his country some breathing space after previous turmoils. His successful campaign and replenishment of funds meant that he could continue his wars against Iran's archrival and neighbour, the Ottoman Empire.[45]

North Caucasus, Central Asia, Arabia, and the second Ottoman war

The Indian campaign was the zenith of Nader's career. After his return from India, Nader fell out with his eldest son Reza Qoli Mirza, who had ruled Persia during his father's absence. Reza had behaved highhandedly and somewhat cruelly but he had kept the peace in Persia. Having heard a rumour that Nader was dead, he had prepared to seize the throne by having the Safavid royal captives, Tahmasp and his nine-year-old son Abbas III, executed. On hearing the news, Reza's wife, who was Tahmasp's sister, committed suicide. Nader was not pleased with the young man's behaviour and humiliated him by removing him from the post of viceroy, but he took him on his expedition to conquer territory in Transoxiana. Nader became increasingly despotic as his health declined markedly. In 1740 he conquered Khanate of Khiva. After the Persians had forced the Uzbek khanate of Bukhara to submit, Nader wanted Reza to marry the khan's elder daughter because she was a descendant of his role model Genghis Khan, but Reza flatly refused and Nader married the girl himself. Nader also conquered Khwarezm on this expedition into Central Asia.[46]

Nader now decided to punish Daghestan for the death of his brother Ebrahim Qoli on a campaign a few years earlier. In 1741, while Nader was passing through the forest of Mazandaran on his way to fight the Daghestanis, an assassin took a shot at him but Nader was only lightly wounded. He began to suspect his son was behind the attempt and confined him to Tehran. Nader's increasing ill health made his temper ever worse. Perhaps it was his illness that made Nader lose the initiative in his war against the Lezgin tribes of Daghestan. Frustratingly for him, they resorted to guerrilla warfare and the Persians could make little headway against them.[47] Though Nader managed to take most of Dagestan during his campaign, the effective guerrilla warfare as deployed by the Lezgins, but also the Avars, Laks and Dargins made the Iranian re-conquest of this particular North Caucasian region this time a short lived one; several years later, Nader was forced to withdraw. During the same period, Nader accused his son of being behind the assassination attempt in Mazandaran. Reza angrily protested his innocence, but Nader had him blinded as punishment, although he immediately regretted it. Soon afterwards, Nader started executing the nobles who had witnessed his son's blinding. In his last years, Nader became increasingly paranoid, ordering the assassination of large numbers of suspected enemies.

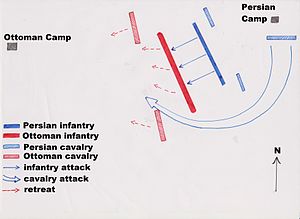

With the wealth he gained, Nader started to build a Persian navy. With lumber from Mazandaran and Gilan, he built ships in Bushehr and order to build new artillery in Amol. He also purchased thirty ships in India.[29] He recaptured the island of Bahrain from the Arabs. In 1743, he conquered Oman and its main capital Muscat. In 1743, Nader started another war against the Ottoman Empire. Despite having a huge army at his disposal, in this campaign Nader showed little of his former military brilliance. It ended in 1746 with the signing of a peace treaty, in which the Ottomans agreed to let Nader occupy Najaf.[48]

Military

The military forces of the Afsharid dynasty of Persia had their origins in the relatively obscure yet bloody inter-factional violence in Khorasan during the collapse of the Safavid state. The small band of warriors under local warlord Nader Qoli of the Turkomen Afshar tribe in north-east Iran were no more than a few hundred men. Yet at the height of Nader's power as the king of kings, Shahanshah, he commanded an army of 375,000 fighting men which constituted the single most powerful military force of its time,[49][50] led by one of the most talented and successful military leaders of history.[51]

After the assassination of Nader Shah at the hands of a faction of his officers in 1747, Nader's powerful army fractured as the Afsharid state collapsed and the country plunged into decades of civil war. Although there were numerous Afsharid pretenders to the throne, (amongst many other), who attempted to regain control of the entire country, Persia remained a fractured political entity in turmoil until the campaigns of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar toward the very end of the eighteenth century reunified the nation.

Civil war and downfall of the Afsharids

After Nader's death in 1747, his nephew Ali Qoli (who may have been involved in the assassination plot) seized the throne and proclaimed himself Adel Shah ("The Just King"). He ordered the execution of all Nader's sons and grandsons, with the exception of the 13-year-old Shahrokh, the son of Reza Qoli.[53] Meanwhile, Nadir's former treasurer, Ahmad Shah Abdali, had declared his independence by founding the Durrani Empire. In the process, the eastern territories were lost and in the following decades became part of Afghanistan, the successor-state to the Durrani Empire. The northern territories, Iran's most integral regions, had a different fate. Erekle II and Teimuraz II, who, in 1744, had been made the kings of Kakheti and Kartli respectively by Nader himself for their loyal service,[54] capitalized on the eruption of instability and declared de facto independence. Erekle II assumed control over Kartli after Teimuraz II's death, thus unifying the two as the Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, becoming the first Georgian ruler in three centuries to preside over a politically unified eastern Georgia,[55] and due to the frantic turn of events in mainland Iran he would be able to remain de facto autonomous through the Zand period.[56] Under the successive Qajar dynasty, Iran managed to restore Iranian suzerainty over the Georgian regions, until they would be irrevocably lost in the course of the 19th century, to neighbouring Imperial Russia.[57] Many of the rest of the territories in the Caucasus, comprising modern-day [Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Dagestan, broke away into various khanates. Until the advent of the Zands and Qajars, its rulers had various forms of autonomy, but stayed vassals and subjects to the Iranian king.[58] Under the early Qajars, these territories in Transcaucasia and Dagestan would all be fully reincorporated into Iran, but eventually permanently lost as well (alongside Georgia), in the course of the 19th century to Imperial Russia through the two Russo-Persian Wars of the 19th century.[57]

Adel made the mistake of sending his brother Ebrahim to secure the capital Isfahan. Ebrahim decided to set himself up as a rival, defeated Adel in battle, blinded him and took the throne. Adel had reigned for less than a year. Meanwhile, a group of army officers freed Shahrokh from prison in Mashhad and proclaimed him shah in October 1748. Ebrahim was defeated and died in captivity in 1750 and Adel was also put to death at the request of Nader Shah's widow. Shahrokh was briefly deposed in favour of another puppet ruler Soleyman II but, although blinded, Shahrokh was restored to the throne by his supporters. He reigned in Mashhad and from the 1750s his territory was mostly confined to the city and its environs. He also faced the Durrani invasions into Khorasan, eventually becoming subjugated to them in Ahmad Shah's second campaign.[52] In 1796 Mohammad Khan Qajar, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, seized Mashhad and tortured Shahrokh to force him to reveal the whereabouts of Nader Shah's treasures. Shahrokh died of his injuries soon after and with him the Afsharid dynasty came to an end.[59][60] One of Shahrokh's sons, Nader Mirza, revolted in 1797 upon the death of Agha Mohammad Khan Qajar but the revolt was crushed and he was executed in April 1803. Shahrokh's descendants continue into the 21st century under the Afshar Naderi surname.

Religious policy

The Safavids had introduced Shi'a Islam as the state religion of Iran. Nader was brought up as a Shi'a [61] but later sympathised and desired unity with the Sunni[62] faith as he gained power and began to push into the Ottoman Empire. He believed that Safavid Shi'ism had intensified the conflict with the Sunni Ottoman Empire. His army was a mix of Shi'a and Sunni (with a notable minority of Christians) and included his own Qizilbash as well as Uzbeks, Afghans, Christian Georgians and Armenians,[63][64] and others. He wanted Persia to adopt a form of Shi'a Islam that would be more acceptable to Sunnis and suggested that Persia adopt a form of Shi'ism he called "Ja'fari", in honour of the sixth Shi'a Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq. He banned certain Shi'a practices which were particularly offensive to Sunnis, such as the cursing of the first three caliphs. Personally, Nader is said to have been indifferent toward religion and the French Jesuit who served as his personal physician reported that it was difficult to know which religion he followed and that many who knew him best said that he had none.[59] Nader hoped that "Ja'farism" would be accepted as a fifth school (mazhab) of Sunni Islam and that the Ottomans would allow its adherents to go on the hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca, which was within their territory. In the subsequent peace negotiations, the Ottomans refused to acknowledge Ja'farism as a fifth mazhab but they did allow Persian pilgrims to go on the hajj. Nader was interested in gaining rights for Persians to go on the hajj in part because of revenues from the pilgrimage trade.[29] Nader's other primary aim in his religious reforms was to weaken the Safavids further since radical Shi'a Islam had always been a major element in support for the dynasty. He had the chief mullah of Persia strangled after he was heard expressing support for the Safavids. Among his reforms was the introduction of what came to be known as the kolah-e Naderi. This was a hat with four peaks which symbolised the first four caliphs.

Flag

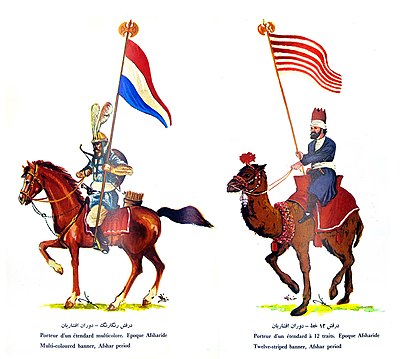

Nader Shah consciously avoided the using the colour green, as green was associated with Shia Islam and the Safavid dynasty.[65]

The two imperial standards were placed on the right of the square already mentioned: one of them was in stripes of red, blue, and white, and the other of red, blue, white, and yellow, without any other ornament: though the old standards required 12 men to move them, the SHAH lengthened their staffs, and made them yet heavier; he also put new colours of silk upon them, the one red and yellow striped, the other yellow edged with red: they were made of such an enormous size, to prevent their being carried off by the enemy, except by an entire defeat. The regimental colours were a narrow slip of silk, sloped to a point, some were red, some white, and some striped.[66][67]

Navy Admiral flag being a white ground with a red Persian Sword in the middle.[68] Although based on the writings of Jonas Hanway, we can see that the flags of the army regiments of King Nader were three-eared, but we cannot come to a conclusion about whether the royal flags of that time were three-eared or four-eared.

Gallery

Afsharians parade in Persepolis

Notes

References

- ^ Katouzian, Homa (2003). Iranian History and Politics. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 0-415-29754-0.

Indeed, since the formation of the Ghaznavids state in the tenth century until the fall of Qajars at the beginning of the twentieth century, most parts of the Iranian cultural regions were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, the official language was Persian, the court literature was in Persian, and most of the chancellors, ministers, and mandarins were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability.

- ^ "HISTORIOGRAPHY vii. AFSHARID AND ZAND PERIODS – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Archived from the original on 2018-12-25. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

Afsharid and Zand court histories largely followed Safavid models in their structure and language, but departed from long-established historiographical conventions in small but meaningful ways.

- ^ ", V. Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, vol. 9, no. 4, 1939, pp. 1119–23. JSTOR

- ^ "THE TURKISH INSCRIPTION OF KALĀT-İ NĀDIRĪ", Tourkhan Gandjeï, Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, Vol. 69 (1977), pp. 45-53 (10 pages). JSTOR

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2008). A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind. New York: Basic Books. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-465-00888-9. OCLC 182779666.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2008). A History of Iran: Empire of the Mind. New York: Basic Books. pp. 160, 167. ISBN 978-0-465-00888-9. OCLC 182779666.

- ^ Aliasghar Shamim, Iran during the Qajar Reign, Tehran: Scientific Publications, 1992, p. 287

- ^ a b Amanat 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Amanat 2017, pp. 145–156.

- ^ Pickett, James (2016). "Nadir Shah's Peculiar Central Asian Legacy: Empire, Conversion Narratives, and the Rise of New Scholarly Dynasties". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 48 (3): 491–510. doi:10.1017/S0020743816000453. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 43998158. S2CID 159600918.

- ^ Tucker, Ernest (2012). "Afshārids". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830. Archived from the original on 2022-08-09. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

The Afshārids (r. 1149–1210/1736–96) were a Persian dynasty founded by Nādir Shāh Afshār, replacing the Ṣafavid dynasty.

- ^ Lockhart, L., "Nadir Shah: A Critical Study Based Mainly upon Contemporary Sources", London: Luzac & Co., 1938, 21 :"Nadir Shah was from a Turkmen tribe and probably raised as a Shiʿa, though his views on religion were complex and often pragmatic"

- ^ Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia, Vol.1. ABC Clio, LLC. p. 408. ISBN 978-1-59884-336-1."This event marked the twilight of the Safavid power but also served as a launching pad for an Afshar Turkoman commander named Nadir Shah."

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. back cover. "Nader Shah, ruler of Persia from 1736 to 1747, embodied ruthless ambition, energy, military brilliance, cynicism and cruelty"

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 17–19. "His father was of lowly but respectable status, a herdsman of the Afshar tribe ... The Qereqlu Afshars to whom Nader's father belonged were a semi-nomadic Turcoman tribe settled in Khorasan] in north-eastern Iran ... The tribes of Khorasan were for the most part ethnically distinct from the Persian-speaking population, speaking Turkic or Kurdish languages. Nader's mother tongue was a dialect of the language group spoken by the Turkic tribes of Iran and Central Asia, and he would have quickly learned Persian, the language of high culture and the cities as he grew older. But the Turkic language was always his preferred everyday speech, unless he was dealing with someone who knew only Persian."

- ^ Cambridge History of Iran Volume 7, pp. 2–4

- ^ Amanat 2017, p. 443.

- ^ Amanat 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Amanat 2019, p. 33.

- ^ Encyclopædia Iranica Archived 2020-05-26 at the Wayback Machine : "Born in November 1688 into a humble pastoral family, then at its winter camp in Darra Gaz in the mountains north of Mashad, Nāder belonged to a group of the Qirqlu branch of the Afšār Turkmen."

- ^ Encyclopædia Iranica[permanent dead link]

- ^ Martin, Samuel Elmo (1997). Uralic And Altaic Series. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 0-7007-0380-2. Archived from the original on 2020-06-02. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ Michael Axworthy Iran: Empire of the Mind (Penguin, 2008) pp.153–156

- ^ Dowling, Timothy C. (2 December 2014). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond ... Abc-Clio. ISBN 978-1-59884-948-6. Archived from the original on 10 April 2023. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ^ Tucker, Ernest (2006). "Nāder Shah". Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ^ "Dataci.Net İstanbul Antlaşması (1736)".

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 57–74

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 75–116

- ^ a b c Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Elton L. Daniel, "The History of Iran" (Greenwood Press 2000) p. 94

- ^ Lawrence Lockhart Nadir Shah (London, 1938)

- ^ a b c d e Fisher et al. 1991, pp. 34.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, pp. 36.

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, pp. 35.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 137–174

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Raghunath Rai. "History". p. 19 FK Publications ISBN 81-87139-69-2

- ^ David Marshall Lang. Russia and the Armenians of Transcaucasia, 1797-1889: a documentary record Archived 2023-04-07 at the Wayback Machine Columbia University Press, 1957 (digitalised March 2009, originally from the University of Michigan) p 142

- ^ "An Outline of the History of Persia During the Last Two Centuries (A.D. 1722-1922)". Edward G. Browne. London: Packard Humanities Institute. p. 33. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 7–8

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 212, 216

- ^ "Rise, Growth and Fall of the Bhangi Misl". CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.6648.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (2004). A History of the Sikhs: 1469-1838. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-567308-1. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 1–16, 175–210

- ^ Axworthy 2006, p. [page needed]

- ^ svat soucek, a history of inner Asia page 195: in 1740 Nadir Shah, the new ruler of Iran, crossed the Amu Darya and, accepting the submission of Muhammad Hakim Bi which was then formalized by the acquiescence of Abulfayz Khan himself, proceeded to attack Khiva. When rebellions broke out in 1743 upon the death of Muhammad Hakim, the shah dispatched the ataliq's son Muhammad Rahim Bi, who had accompanied him to Iran, to quell them. Mohammad hakim bi was ruler of the khanate of bukhara at that time. Page link: "Page 195 a History of Inner Asia Librarum.org". Archived from the original on 2015-06-10. Retrieved 2015-07-16.

- ^ Spencer C. Tucker. "A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East" Archived 2023-04-07 at the Wayback Machine p 739

- ^ Axworthy 2006, pp. 175–274

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2007). "The Army of Nader Shah". Iranian Studies. 40 (5). Informa UK: 635–646. doi:10.1080/00210860701667720. S2CID 159949082.

- ^ Axworthy, Michael (2009). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from tribal warrior to conquering tyrant, . I. B. Tauris

- ^ Axworthy, Michael, "Iran: Empire of the Mind", Penguin Books, 2007. p158

- ^ a b Malcolm, Sir John (1829). The History of Persia: From the Most Early Period to the Present Time. Murray. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ Cambridge History p.59

- ^ Ronald Grigor Suny. "The Making of the Georgian Nation" Archived 2023-04-10 at the Wayback Machine Indiana University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-253-20915-3 p 55

- ^ Yar-Shater, Ehsan. Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. 8, parts 4-6 Archived 2023-04-07 at the Wayback Machine Routledge & Kegan Paul (original from the University of Michigan) p 541

- ^ Fisher et al. 1991, p. 328.

- ^ a b Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond Archived 2023-04-10 at the Wayback Machine p 728-729 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1-59884-948-4

- ^ Encyclopedia of Soviet law By Ferdinand Joseph Maria Feldbrugge, Gerard Pieter van den Berg, William B. Simons, Page 457

- ^ a b Axworthy p.168

- ^ Cambridge History pp.60–62

- ^ Axworthy p.34

- ^ Mattair, Thomas R. (2008). Global security watch--Iran: a reference handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-275-99483-9. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10. Retrieved 2010-09-24.

- ^ "The Army of Nader Shah" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ^ Steven R. Ward. Immortal, Updated Edition: A Military History of Iran and Its Armed Forces Georgetown University Press, 8 jan. 2014 p 52

- ^ Shapur Shahbazi|1999|Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Hanway, Jonas (1753). "XXXVII". An Historical Account of the British Trade over the Caspian Sea: With a Journal of Travels through Russia into Persią. 248-249. London: Mr. Dodsley. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- ^ "An Historical Account of the British Trade over the Caspian Sea Vol.1,2". 1753.

- ^ Nādir Shāh's Campaigns in 'Omān, 1737–1744 By Laurence Lockhart, Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London,Vol. 8, No. 1 (1935), pp. 157–171

Sources

- Amanat, Abbas (1997). Pivot of the Universe: Nasir Al-Din Shah Qajar and the Iranian Monarchy, 1831-1896. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-828-0.

- Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: A Modern History. Yale University Press. pp. 1–992. ISBN 978-0-300-11254-2.

- Amanat, Abbas (2019). "Remembering the Persianate". In Amanat, Abbas; Ashraf, Assef (eds.). The Persianate World: Rethinking a Shared Sphere. Brill. pp. 15–62. ISBN 978-90-04-38728-7.

- Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1-85043-706-2.

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20095-4.

- Rota, Giorgio (2020). "In a League of Its Own? Nāder Šāh and His Empire". In Rollinger, Robert; Degen, Julian; Gehler, Michael (eds.). Short-term Empires in World History. Springer. pp. 215–226.

- Tucker, Ernest (2012). "Afshārids". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.