African red slip ware

African red slip ware, also African Red Slip or ARS, is a category of terra sigillata, or "fine" Ancient Roman pottery produced from the mid-1st century AD into the 7th century in the province of Africa Proconsularis, specifically that part roughly coinciding with the modern country of Tunisia and the Diocletianic provinces of Byzacena and Zeugitana. It is distinguished by a thick-orange red slip over a slightly granular fabric. Interior surfaces are completely covered, while the exterior can be only partially slipped, particularly on later examples.

By the 3rd century AD, African red slip appears on sites throughout the Mediterranean and in the major cities of Roman Europe. It was the most widely distributed representative of the sigillata tradition in the late-Roman period, and occasional imports have been found as far afield as Britain in the 5th-6th centuries.[1] African red slip ware was still widely distributed in the 5th century but after that time the volume of production and trade may well have declined. While the latest forms continued into the 7th century and are found in such major cities as Constantinople and Marseille, the breakup of commercial contacts that typified the later 7th century coincides with the final decline of the African red slip industry.

The production and success of African red slip is probably closely tied to the agricultural productivity of Rome's North African provinces, as indicated in part by the contemporaneous distribution of Roman-period North African amphoras.

Vessel forms

From about the 4th century, competent copies of the fabric and forms were also made in several other regions, including Asia Minor, the eastern Mediterranean and Egypt. Over the long period of production, there was obviously much change and evolution in both forms and fabrics. Both Italian and Gaulish plain forms influenced ARS in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD (for example, Hayes Form 2, the cup or dish with an outcurved rim decorated with barbotine leaves, is a direct copy of the samian forms Dr.35 and 36, made in South and Central Gaul),[2] but over time a distinctive ARS repertoire developed.

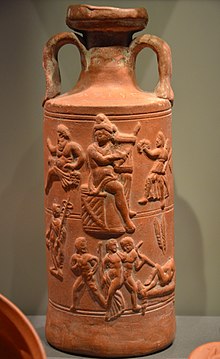

There was a wide range of dishes and bowls, many with rouletted or stamped decoration, and closed forms such as tall ovoid flagons with appliqué ornament (Hayes Form 171). The ambitious large rectangular dishes with relief decoration in the centre and on the wide rims (Hayes Form 56), were clearly inspired by decorated silver platters of the 4th century, which were made in rectangular and polygonal shapes as well as in the traditional circular form.

Surface decoration

A wide range of bowls, dishes and flagons were made in ARS, but the technique of making entire relief-decorated vessels in moulds was discontinued.[3] Instead, appliqué motifs were frequently used where decoration in relief was required, separately made and applied to the vessel before drying and firing. Stamped motifs were also a favoured form of decoration, and decorative motifs reflected not only the Graeco-Roman traditions of the Mediterranean, but eventually the rise of Christianity as well: there is a great variety of monogram crosses and plain crosses amongst the stamps in the later centuries. Similar forms and fabrics were made for more local distribution in Egypt, which had its own very active and diverse ceramic traditions in the Roman period.

Surface decoration of ARS is relatively simple during the first three centuries of production, with occasional rouletting, barbotine motifs and some appliqué being typical. In the 4th century applied decoration becomes common. By the 5th century stamped central motifs such as animals, crosses and humans are common on larger plates. Paralleling developments in other visual media, gladiatorial scenes and references to pagan mythology come to be replaced by Christian figures. In the last phase of production, surface treatment consists of light spiral burnishing on some plates and rouletting around the floor of certain bowls.

Main typologies

In 1972 John Hayes published a type series running from form 1 to 200, with forms 112-120 remaining unused.[4] A supplement appeared in 1980.[5] In addition to other previous work, Hayes made use of Waage's work in both Antioch and the Athenian Agora, as well as Lamboglia's in Ventimiglia. Michael Fulford's publication of the British excavations at Avenue du Président Habib Bourguiba, Salammbo in Carthage expanded on the work of Hayes.[6] Carandini's typology, published in Enciclopedia dell'arte antica classica e orientale, is also important.[7] Michael Mackensen offers an alternate typology for later forms based on his work in northern Tunisia.[8] Michel Bonifay has also collected previous scholarship alongside his own observations.[9]

Centers of production

Some major ARS centres in central Tunisia are Sidi Marzouk Tounsi, Henchir el-Guellal (Djilma),[10] and Henchir es-Srira,[11] all of which have ARS lamp artifacts attributed to them by the microscopic chemical makeup of the clay fabric as well as macroscopic style prevalent in that region.

Notes

- ^ Tyers 1996, pp.80-82

- ^ Hayes 1972, p. 19–20.

- ^ For the detailed typology and distribution maps, see Hayes 1972 and Hayes 1980

- ^ Hayes, John. (1972). Late Roman Pottery. London: British School at Rome (hardcover, ISBN 0-904152-00-6)

- ^ Hayes, John. 1980. A Supplement to Late Roman Pottery. London: British School at Rome ISBN 0-904152-10-3

- ^ Fulford, Michael & Peacock, David. (1984). The Avenue du President Habib Bourguiba, Salammbo: the pottery and other ceramic objects from the site excavations at Carthage. (The British Mission 1.2.) Sheffield: University of Sheffield, Department of Prehistory and Archaeology.

- ^ 1981. Enciclopedia dell'arte antica classica e orientale. Atlante delle Forme Ceramiche I, Ceramica Fine Romana nel Bacino Mediterraneo (Medio e Tardo Impero). Rome: Istituto della Enciclopedia italiana.

- ^ Mackensen, Michael (1993). Die spätantiken Sigillata- und Lampentöpfereien von el Mahrine (Nordtunesien): Studien zur nordafrikanischen Feinkeramik des 4. bis 7. Jahrhunderts. Munich: Beck (hardcover, ISBN 978-3-406-37015-1)

- ^ Bonifay, Michel. 2004. Études sur la céramique romaine tardive d’Afrique. (British Archaeological Reports International Series 1301) Oxford: B. A. R.

- ^ 34°42′18″N 9°21′58″E / 34.7049689°N 9.3661589°E Hitchner, R.; R. Warner; R. Talbert; T. Elliott; S. Gillies (20 October 2012). "Places: 324723 (Henchir-el-Guellal)". Pleiades. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

- ^ 35°26′15″N 9°22′09″E / 35.437423°N 9.3690949°E Hitchner, R.; R. Warner; R. Talbert; T. Elliott; S. Gillies (20 October 2012). "Places: 324738 (Henchir-es-Srira)". Pleiades. Retrieved January 14, 2014.

References

- Hayes, John. (1972). Late Roman Pottery. London: British School at Rome (hardcover, ISBN 0-904152-00-6)

- Hayes, John. (1980). "Supplement to Late Roman Pottery". London: British School at Rome. Worldcat

- Mackensen, Michael (1993). Die spätantiken Sigillata- und Lampentöpfereien von el Mahrine (Nordtunesien): Studien zur nordafrikanischen Feinkeramik des 4. bis 7. Jahrhunderts. Munich : Beck (hardcover, ISBN 978-3-406-37015-1)

- Tyers, Paul (1996). Roman Pottery in Britain, London: B. T. Batsford ISBN 0-7134-7412-2

Further reading

- Hayes, John W. 1972. Late Roman Pottery. London: British School at Rome.

- Hayes, John W. 1997. Handbook of Mediterranean Roman Pottery. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Peacock, D. P. S. 1982. Pottery In the Roman World: An Ethnoarchaeological Approach. London: Longman.

- Peña, J. Theodore. 2007. Roman Pottery In the Archaeological Record. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Robinson, Henry Schroder. 1959. Pottery of the Roman Period: Chronology. Princeton, NJ: American School of Classical Studies at Athens.