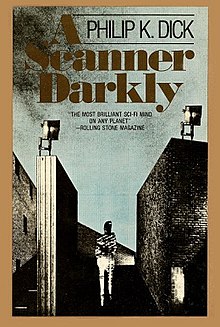

A Scanner Darkly

First edition (hardcover) | |

| Author | Philip K. Dick |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction, paranoid fiction, philosophical literature |

| Publisher | Doubleday |

Publication date | 1977 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 220 (1st edition) |

| ISBN | 0-385-01613-1 (1st edition) |

| OCLC | 2491488 |

| 813/.5/4 | |

| LC Class | PZ4.D547 Sc PS3554.I3 |

A Scanner Darkly is a science fiction novel by American writer Philip K. Dick, published in 1977. The semi-autobiographical story is set in a dystopian Orange County, California, in the then-future of June 1994, and includes an extensive portrayal of drug culture and drug use (both recreational and abusive). The novel is one of Dick's best-known works and served as the basis for a 2006 film of the same name, directed by Richard Linklater.

Plot summary

The protagonist is Bob Arctor, member of a household of drug users, who is also living a double life as an undercover police agent assigned to spy on Arctor's household. Arctor shields his identity from those in the drug subculture and from the police. (The requirement that narcotics agents remain anonymous, to avoid collusion and other forms of corruption, becomes a critical plot point late in the book.) While posing as a drug user, Arctor becomes addicted to "Substance D" (also referred to as "Slow Death", "Death" or "D"), a powerful psychoactive drug. A conflict is Arctor's love for Donna, a drug dealer, through whom he intends to identify high-level dealers of Substance D.

When performing his work as an undercover agent, Arctor goes by the name "Fred" and wears a "scramble suit" that conceals his identity from other officers. Then he is able to sit in a police facility and observe his housemates through "holo-scanners", audio-visual surveillance devices that are placed throughout the house. Arctor's use of the drug causes the two hemispheres of his brain to function independently or "compete". When Arctor sees himself in the videos saved by the scanners, he does not realize that it is him. Through a series of drug and psychological tests, Arctor's superiors at work discover that his addiction has made him incapable of performing his job as a narcotics agent. They do not know his identity because he wears the scramble suit, but when his police supervisor suggests to him that he might be Bob Arctor, he is confused and thinks it cannot be possible.

Donna takes Arctor to "New-Path", a rehabilitation clinic, just as he begins to experience the symptoms of Substance D withdrawal. It is revealed that Donna has been a narcotics agent all along, working as part of a police operation to infiltrate New-Path and determine its funding source. Without his knowledge, Arctor has been selected to penetrate the organization. As part of the rehab program, Arctor is renamed "Bruce" and forced to participate in cruel group-dynamic games, intended to break the will of the patients.

The story ends with Bruce working at a New-Path farming commune, where he is experiencing a serious neurocognitive deficit, after withdrawing from Substance D. Although considered by his handlers to be nothing more than a walking shell of a man, "Bruce" manages to spot rows of blue flowers growing hidden among rows of corn and realizes that the blue flowers are Mors ontologica, the source of Substance D. The book ends with Bruce hiding a flower in his shoe to give to his "friends"—undercover police agents posing as recovering addicts at the Santa Ana New-Path facility—on Thanksgiving.

Autobiographical nature

A Scanner Darkly is a fictionalized account of real events, based on Dick's experiences in the 1970s drug culture. Dick said in an interview, "Everything in A Scanner Darkly I actually saw."[1]

Between mid-1970 (when his fourth wife Nancy left him) and mid-1972, Dick lived semi-communally with a rotating group of mostly teenage drug users at his home in Marin County, described in a letter as being located at 707 Hacienda Way, Santa Venetia.[2] Dick explained, "[M]y wife Nancy left me in 1970. I got mixed up with a lot of street people, just to have somebody to fill the house. She left me with a four-bedroom, two-bathroom house and nobody living in it but me. So I just filled it with street people and I got mixed up with a lot of people who were into drugs."[1]

During this period, the author ceased writing completely and became fully dependent upon amphetamines, which he had been using intermittently for many years. "I did take amphetamines for years in order to be able to—I was able to produce 68 final pages of copy a day," Dick said.[1]

The character of Donna was inspired by an older teenager who became associated with Dick sometime in 1970; though they never became lovers, the woman was his principal female companion until early 1972, when Dick left for Canada to deliver a speech to a Vancouver science fiction convention. This speech, "The Android and the Human", served as the basis for many of the recurring themes and motifs in the ensuing novel. Another turning point in this timeframe for Dick is the alleged burglary of his home and theft of his papers.

After delivering "The Android and the Human", Dick became a participant in X-Kalay (a Canadian Synanon-type recovery program), effortlessly convincing program caseworkers that he was nursing a heroin addiction to do so. Dick's recovery program participation was portrayed in the posthumously released book The Dark Haired Girl (a collection of letters and journals from this period, most of a romantic nature). It was at X-Kalay, while doing publicity for the facility, that he devised the notion of rehab centers being used to secretly harvest drugs (thus inspiring the book's New-Path clinics).

In the afterword, Dick dedicates the book to those of his friends—he includes himself—who had experienced debilitation or death as a result of their drug use. Mirroring the epilogue are the involuntary goodbyes that occur throughout the story—the constant turnover and burn-out of young people that lived with Dick during those years.[3] In the afterword, he states that the novel is about "some people who were punished entirely too much for what they did",[4] and that "drug misuse is not a disease, it is a decision, like the decision to move out in front of a moving car".[4]

Background and publication

A Scanner Darkly was one of the few Dick novels to gestate over a long period of time. By February 1973, in an effort to prove that the effects of his amphetamine usage were merely psychosomatic, the newly clean-and-sober author had already prepared a full outline.[5] A first draft was in development by March.[6] This labor was soon supplanted by a new family and the completion of Flow My Tears, The Policeman Said (left unfinished in 1970), which was finally released in 1974 and received the prestigious John W. Campbell Award.[7] Additional preoccupations were the mystical experiences of early 1974 that eventually served as a basis for VALIS and the Exegesis journal; a screenplay for an unproduced film adaptation of 1969's Ubik; occasional lectures; and the expedited completion of the deferred Roger Zelazny collaboration Deus Irae in 1975.

Because of its semi-autobiographical nature, some of A Scanner Darkly was torturous to write. Tessa Dick, Philip's wife at the time, once stated that she often found her husband weeping as the sun rose after a night-long writing session. Tessa has given interviews stating that "when he was with me, he wrote A Scanner Darkly [in] under two weeks. But we spent three years rewriting it" and that she was "pretty involved in his writing process [for A Scanner Darkly]".[8] Tessa stated in a later interview that she "participated in the writing of A Scanner Darkly" and said that she "consider[s] [her]self the silent co-author". Philip wrote a contract giving Tessa half of all the rights to the novel, which stated that Tessa "participated to a great extent in writing the outline and novel A Scanner Darkly with me, and I owe her one half of all income derived from it".[9]

There was also the challenge of transmuting the events into "science fiction", as Dick felt that he could not sell a mainstream or literary novel after several previous failures.[citation needed][10] Providing invaluable aid in this field was Judy-Lynn del Rey, head of Ballantine Books' SF division, which had optioned the book. Del Rey suggested the timeline change to 1994 and emphasized the more futuristic elements of the novel, such as the "scramble suit" employed by Fred (which, incidentally, emerged from one of the mystical experiences). Yet much of the dialogue spoken by the characters used hippie slang, dating the events of the novel to their "true" time-frame of 1970–72.

Upon its publication in 1977, A Scanner Darkly was hailed by ALA Booklist as "his best yet!" Brian Aldiss lauded it as "the best book of the year", while Robert Silverberg praised the novel as "a masterpiece of sorts, full of demonic intensity", but concluded that "it happens also not to be a very successful novel... a failure, but a stunning failure".[11] Spider Robinson panned the novel as "sometimes fascinating, sometimes hilarious, [but] usually deadly boring".[12] Sales were typical for the SF genre in America, but hardcover editions were issued in Europe, where all of Dick's works were warmly received. It was nominated for neither the Nebula nor the Hugo Award but was awarded the British version (the BSFA) in 1978[13] and the French equivalent (Graouilly d'Or) upon its publication there in 1979.[14] It also was nominated for the Campbell Award in 1978 and placed sixth in the annual Locus poll.[15]

The title of the novel refers to the Biblical phrase "Through a glass, darkly", from the King James Version of 1 Corinthians 13. Passages from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's play Faust are also referred to throughout the novel. The same-titled film by Ingmar Bergman has also been cited as a reference for the book,[16] the film depicting the similar descent into madness and schizophrenia of its lead character portrayed by Harriet Andersson.[17]

Adaptations

Film

The rotoscoped film A Scanner Darkly was authorized by Dick's estate. It was released in July 2006 and stars Keanu Reeves as Fred/Bob Arctor and Winona Ryder as Donna. Rory Cochrane, Robert Downey Jr., and Woody Harrelson co-star as Arctor's drugged-out housemates and friends. The film was directed by Richard Linklater.

Audiobook

An unabridged audiobook version, read by Paul Giamatti, was released in 2006 by Random House Audio to coincide with the release of the film adaptation. It runs approximately 9.5 hours over eight compact discs. This version is a tie-in, using the film's poster as cover art.[18][19]

See also

Citations

- ^ a b c Uwe Anton; Werner Fuchs; Frank C. Bertrand (Spring 1996). "So I Don't Write About Heroes: An Interview with Philip K. Dick". SF EYE. pp. 37–46. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved June 23, 2015.

- ^ Redfern, Nick (February 2010). "The Strange Tale of Solarcon-6". Fortean Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2015.

- ^ Philip K. Dick (October 18, 2011). A Scanner Darkly. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 288–289. ISBN 978-0-547-57217-8. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Philip K. Dick (October 18, 2011). A Scanner Darkly. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-547-57217-8. Retrieved August 24, 2012.

- ^ Dick, Philip K. (February 28, 1973). "Letter to Scott Meredith". Letters. Philip K. Dick Trust. Archived from the original on June 2, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ Dick, Philip K. (March 20, 1973). "Letter to Scott Meredith". Letters. Philip K. Dick Trust. Archived from the original on June 2, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "1975 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ Knight, Annie (November 1, 2002). "About Philip K. Dick: An interview with Tessa, Chris, and Ranea Dick". Deep Outside SFF. Retrieved June 6, 2007.

- ^ "An interview with Tessa Dick".

- ^ Dick, Philip K. The Shifting Realities of Philip K. Dick: Selected Literary and Philosophical Writings.

- ^ "Books", Cosmos, September 1977, p. 39.

- ^ "Galaxy Bookshelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, August 1977, p. 141.

- ^ "1978 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved September 27, 2009.

- ^ "thephildickian.com – Award Winning Authors". Archived from the original on October 18, 2010. Retrieved January 2, 2007.

- ^ Locus Index to SF Awards Archived March 27, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kucukalic, Lejla (2009). Philip K. Dick: Canonical Writer of the Digital Age. New York: Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 9780203886847.

- ^ "Through a Glass Darkly". IMDb. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ A Scanner Darkly by Philip K. Dick – Audiobook – Random House Audio ISBN 978-0-7393-2392-2

- ^ "Review of A Scanner Darkly by Philip K. Dick: SFFaudio". July 3, 2006.

General and cited sources

- Bell, V. (2006). "Through a scanner darkly: Neuropsychology and psychosis in A Scanner Darkly" . The Psychologist, 19 (8), 488–489.

- Kosub, Nathan (2006). "Clearly, Clearly, Dark-Eyed Donna: Time and A Scanner Darkly", Senses of Cinema: An Online Film Journal Devoted to the Serious and Eclectic Discussion of Cinema, October–December; 41: [no pagination].

- Prezzavento, Paolo (20060. "Allegoricus semper interpres delirat: Un oscuro scrutare tra teologia e paranoia", Trasmigrazioni, eds. Valerio Massimo De Angelis and Umberto Rossi, Firenze, Le Monnier, 2006, pp. 225–36.

- Sutin, Lawrence (2005). Divine Invasions: A Life of Philip K. Dick. Carroll & Graf.

External links

- A Scanner Darkly at Worlds Without End

- "Darkness in literature: Philip K Dick's A Scanner Darkly," Damien Walter, The Guardian, 17 December 2012