76 Place at Market East

| |

Renderings | |

| |

| Location | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°57′07″N 75°09′24″W / 39.952076°N 75.156612°W |

| Public transit | Broad Street Line Ridge Spur |

| Type | Arena |

| Capacity | 18,500 |

| Construction | |

| Construction cost | US$1.3 billion (estimated) |

| Architect | Gensler |

| Project manager | David Adelman |

| General contractor | AECOM |

| Website | |

| 76place | |

76 Place at Market East was a proposed 18,500-capacity indoor arena planned for Center City, Philadelphia that would have served as the home of the city's National Basketball Association (NBA) team, the Philadelphia 76ers. Originally planned for a 2031 opening to coincide with the expiration of the team's current lease of the Wells Fargo Center in South Philadelphia, the arena would have been located along the north side of Market Street between 10th and 11th Streets, extending to Cuthbert Street, occupying what is now the western third of Fashion District Philadelphia and the defunct Philadelphia Greyhound Terminal.

The development of 76 Place, with an estimated cost of $1.3 billion, was led by the 76ers managing entity Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment (HBSE)—co-founded by 76ers managing partners Josh Harris and David Blitzer—along with real estate developer and HBSE limited partner David Adelman. 76 Place faced significant opposition from some community groups, particularly in regards to its effects on neighboring Chinatown. According to several polls, a significant majority of the public opposed the project.[1][2][3]

Despite being granted approval by the Philadelphia City Council, HBSE abandoned plans for 76 Place in January 2025 and announced a deal with Comcast Spectacor to build a new arena for the 76ers and the Philadelphia Flyers of the National Hockey League (NHL) at the present South Philadelphia Sports Complex.

Background

The Sixers currently play at the Wells Fargo Center, part of the South Philadelphia Sports Complex, along with Lincoln Financial Field and Citizens Bank Park.[4] In 2011, Comcast Spectacor sold the Sixers to Apollo Global Management, led by Josh Harris.[5] The team's current ownership, Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment (HBSE), was formed by Harris and investment partner David Blitzer in 2017.[6]

The Wells Fargo Center, built in 1996 to accommodate the Sixers and Flyers, is owned by Comcast Spectacor, allowing them to profit off secondary events such as concerts instead of HBSE.[7] The South Philadelphia Sports Complex has been critiqued as lacking access to public transportation—it is only served by the Broad Street Line—and there are few restaurants and bars nearby.[4] The Wells Fargo Center underwent extensive renovations in 2019 and 2020 including the installation of a new 4K resolution scoreboard and expanded luxury suites.[8]

Talk of a new arena increased by the mid-2010s when HBSE began referring to the Wells Fargo Center as simply "The Center", due to a dispute with naming rights holder Wells Fargo.[9] In 2020, the team proposed a partially publicly-funded plan that would build a new arena at Penn's Landing before being outbid for the site by the Durst Organization.[10] Plans to build large Center City projects have been unsuccessful in the recent past.[11] The Philadelphia Phillies of Major League Baseball (MLB) attempted to build a downtown stadium in Chinatown, Philadelphia, but neighbors protested the decision.[11][12][13] Eight years later, residents once again protested and blocked the proposed construction of Foxwoods Casino Philadelphia.[12][13]

Fashion District Philadelphia

Fashion District Philadelphia is an indoor shopping mall located along Market Street. Opened in 2019, it is anchored by Burlington, Primark, AMC Theatres, and Round One Entertainment.[14] PREIT, which co-owned Fashion District Philadelphia, filed for bankruptcy protection in 2020, and Macerich, the other co-owner took substantial control over the mall's operations.[15] The mall lost a number of tenants due to shutdowns during the COVID-19 pandemic.[15] Macerich endorsed the plan to convert part of Fashion District Philadelphia into an arena and referred to it as a "natural evolution" of the property.[15]

Fashion District Philadelphia was preceded by another indoor mall, Gallery at Market East, which opened in 1977, but by the mid-2000s, had significantly declined as a result of losing a significant number of anchors, which were replaced by lower end stores. It closed in 2015.[16]

Opposition

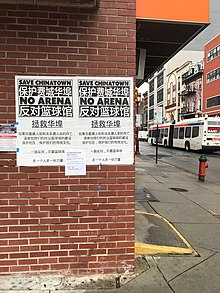

Impact on Chinatown

76 Place at Market East would have been located one block from Chinatown.[7] Asian Americans United, a local advocacy group, opposed the arena following the developers release their plans.[7][17] Steven Zhu, the President of the Chinese Restaurant Association, said in a statement "We know these big sports arenas do not contribute to the neighborhoods that they are in; they serve only their own needs and their own profits."[7][18] Zhu also used Capital One Arena as a cautionary tale given that the Chinese population and number of Chinese restaurants have declined significantly in Chinatown, Washington, D.C. since the arena's construction.[12]

76 Devcorp vowed to reach a "public benefits agreement" with neighbors and met with local organizations including the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corp.[7] After months of private closed-door meetings, 76 Devcorp failed to win over community members at the first public meeting organized by more than 20 local community organizations in December 2022. At this public meeting, community members voiced their concerns around traffic, community safety, and parking.[19][20]

In January 2023, more than 40 Chinatown community groups, nonprofits, and business organizations announced the "Chinatown Coalition to Oppose the Arena". This coalition has the assistance from the Asian American Legal Defense and Education Fund.[21]

In February 2023, some members of the community criticized Hercules Grigos, a lawyer working with the 76ers' development team. Grigos sent Mark Squilla, a member of the Philadelphia City Council, a revised version of a bill to refinance a downtown parking garage that included an unrelated provision that would make it easier to either close or remove from the city grid Filbert Street between 10th and 11th Street, which is in the vicinity of the proposed arena.[22][23]

Some local residents criticized the plan as it would demolish a block of the Fashion District.[12] Others highlighted the missed opportunity for investors to fund Philadelphia's poorer neighborhoods rather than Center City.[12] Then-Philadelphia City Councilman David Oh speculated that the plan to build the arena may be smoke and mirrors and an attempt for the 76ers to gain concessions from the Wells Fargo Center's owner, Comcast Spectacor.[24]

Accessibility issues

Howard Eskin, a Philadelphia sports talk radio personality, called the proposal one of the "worst ideas for [a] sports arena."[25] He argued that the site has little infrastructure for parking and is in a high-crime area, which would dissuade fans from attending the games.[25] Eskin also stated that because of the little parking in the area that the 76ers would ultimately end up having to bus fans from parking lots that are not in walking distance of the stadium to the games.[26]

Geoff Gordon, president of the Live Nation Entertainment Philadelphia chapter, raised concerns that the new stadium would make it hard for fans to tailgate prior to games.[26]

Decline in city and state tax revenue

Sam Katz, a Philadelphia businessman and the Republican nominee for Mayor of Philadelphia in 1999 and 2003 stated with the exception of Madison Square Garden, no arena located in a city with competing arenas is actually profitable.[27] Therefore, Katz argued that 76 Place at Market East would have been unprofitable and argued that this raises suspicions that the developers will look for public funding from the state.[27] Katz has also said that despite the arena being privately-funded, improvements to the infrastructure such as subways to provide transportation for the fans would have had to be paid for by the city.[27]

A study conducted by Dr. Arthur Acolin, the Bob Filley Endowed Chair in the Department of Real Estate at the University of Washington, found that the construction of 76 Place could have cost Pennsylvania and Philadelphia $1 billion in lost tax revenue.[28] Acolin said "under a relatively conservative scenario, there will be some negative impact on existing businesses due to increased congestion, traffic during the construction period, people avoiding the area as some of the streets will be closed and all the traffic patterns will be disrupted..."[28] Acolin predicted that fans would not patronize local businesses before and after the games, but rather concession stands or newer, fancier restaurants that will open along when the arena does.[28] Responding to Acolin's proposal, Bishop Dwayne Royster said that 76 Place would increase income inequality.[28]

Labor

Members of UNITE HERE employed by Aramark at the South Philadelphia Sports Complex voiced their opposition to the arena. During their September 2024 strike, the union released a statement saying "Before we even talk about building a new arena, we need to make sure that stadium food service jobs are good jobs."[29]

Medical students and employees of nearby Jefferson Medical Center as well as Philadelphia teachers spoke at rallies opposing the arena.[30]

Public officials

Several Pennsylvania officials attended and spoke at a September 7 rally against the proposed arena including state senators Nikil Saval, Chris Rabb and Rick Krajewski and city councilmember Nicholas O'Rourke.[31] Councilmembers Jeffrey Young Jr. and Kendra Brooks also opposed the arena proposal.[32]

Public opinion

In a March 2024 survey by Axios Philadelphia, 81% of respondents preferred Comcast Spectacor's redesign of the South Philadelphia Complex over the Sixers Arena.[33] A poll commissioned by the Save Chinatown Coalition showed 56% of residents opposed to the arena and 18% in favor, with opposition growing to 69% when participants were given "neutral information" about why people support and oppose the arena. Around 60% of respondents said they wanted the Sixers to stay in South Philadelphia, and a similar number said that the Wells Fargo Center is "already in good or excellent condition." Cornell Belcher of the "brilliant corners" polling firm who conducted the survey commented on the results, saying that "the more voters hear about the arena, the less they like it."[34] In a September 2024 poll by Axios Philadelphia, 74% of respondents opposed the arena deal proposed by Mayor Parker that month.[35]

Many protesters gathered both in favor and against the project at Philadelphia city council meetings concerning the arena's construction. In October 2024, a group of protestors against the project disrupted a city council meeting.[36] The protest included hundreds of participants and was organized by No Arena PHL, a coalition started to oppose the planned arena. Since then, protests against the project continued at meetings concerning the project, including at one in December 2024, which was when the city council was supposed to hold another meeting and vote on the project, after the original meeting was postponed.[37] However, it was yet again postponed due to an outburst by protesters.[38] The final vote was held on December 19, 2024, where the city council approved the arena plans, however the vote itself was briefly delayed due to protestors having to be removed from the council floor.[39]

Support

City officials

In September 2024, mayor Cherelle Parker released a statement announcing her support for the proposed arena, despite objections from neighboring Chinatown and other community groups.[40] Councilmember Jim Harrity also voiced his support for the proposal.[32]

Labor

Ryan Boyer, the head of the Philadelphia Building and Construction Trades Council, praised the planned stadium as having the opportunity to "galvanize the construction industry in Philadelphia."[11] Consultants working on the stadium expected as many as 9,000 professionals, trades members and managers to work on the project.[11]

Construction plans

Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment (HBSE), who own and operate the 76ers, hired the architectural firm Gensler to design the arena and the engineering firm AECOM to build it.[11] HBSE limited partner and real estate developer David Adelman managed the project's development.[11][7]

HBSE did not plan to speed up the construction process in order to leave their current lease with the Wells Fargo Center sooner. The arena would have replaced one-third of Fashion District Philadelphia including the AMC Dine-In movie theater and Round 1 Bowling and Amusement.[7] Groundbreaking on the arena was not expected for several years[41] and was opposed by local residents and businesses which the arena would have displaced.[7] HBSE planned to use the site of the Philadelphia Greyhound Terminal on Filbert Street to attract new businesses.[24]

Funding

HBSE stated the project would have been privately funded.[11] However, a previous 30-year agreement that the property taxes for the site would be reduced remains in place through 2035.[11] 76 Devcorp said they were open to accepting partial funding from the government.[42]

Design

76 Place at Market East was expected to have a capacity of 18,500.[11] The site of the arena was chosen because of its location to a number of public transit options.[41]

Approval and cancellation

The project was scheduled to move forward after being approved by the city council on December 19, 2024. Councilmembers Squilla, Johnson, Jones, Driscoll, Lozada, Bass, Phillips, O'Neill, Richardson, Thomas, and Harrity voted for all 11 of the bills needed to move forward with the project, while councilmembers Gauthier, Landau, Young, Brooks, and O'Rourke voted against 10 of them. Gauthier and Landau voted for one of the 11 bills, which proposed the creation of a Philadelphia Chinatown Overlay District, while the other opposing members voted against all 11.[43]

On January 12, 2025, HBSE cancelled plans for 76 Place and announced a deal with Comcast Spectacor for a new arena to be built inside the South Philadelphia Sports Complex.[44] A Philadelphia Inquirer study estimated that hearings, meetings, travel, behind the scenes bargaining and police overtime related to the arena and protests against the arena cost city taxpayers at least $469,000.[45]

References

- ^ Wang, Sophia Neaman, Diamy. "Protesters rally in support of Chinatown following delayed release of 76ers arena impact studies". www.thedp.com. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ D'Onofrio, Mike (October 1, 2024). "What Philadelphians are saying about the Sixers arena deal". Axios Philadelphia.

- ^ Moselle, Aaron (September 4, 2024). "'It isn't just Chinatown': Citywide poll shows little support for Sixers arena proposal". WHYY. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Bontemps, Tim (July 21, 2022). "Sixers unveil plans for downtown arena by '31-32". ESPN.com. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "Comcast finishes sale of 76ers to Harris' group". ESPN.com. July 13, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ "Harris, Blitzer Announce Formation of Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment". www.nba.com. Retrieved September 19, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Prihar, Asha (July 21, 2022). "Who's involved? What's the timeline? All the details about the Sixers' plan for a Center City arena". Billy Penn. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ "You can 'bet' the fan experience at Flyers games is about to be much different". NBC Sports Philadelphia. September 4, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- ^ Shelly, Jared (June 10, 2015). "Why Sixers Execs Refuse to Say "Wells Fargo Center"". Philadelphia Magazine. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ Briggs, Ryan (September 9, 2020). "76ers rejected: N.Y. developer Durst selected for Penn's Landing site". WHYY. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i DiStefano, Joseph N. (July 21, 2022). "The Sixers want to build a new $1.3 billion arena in Center City". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Conde, Ximena; Torrejón, Rodrigo. "Chinatown coalition calls Sixers arena proposal a threat to their neighborhood's identity". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ a b "Timeline – Asian Americans United". Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Scott, Katherine (September 19, 2019). "Fashion District Philadelphia opens in Center City". WPVI-TV. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c Adelman, Jacob (December 17, 2020). "PREIT loses control of Center City's Fashion District mall to its California-based partner". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ McQuade, Dan (March 22, 2015). "It's the End of The Gallery as We Know It (and That's a Shame)". Philadelphia Magazine. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "Asian Americans United – Helping people of Asian ancestry build their communities and unite to challenge oppression". Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ @billy_penn (July 21, 2022). "INBOX: Asian Americans United, an organization that fosters leadership and highlights issues in Philly's Asian American communities, announced a coalition that's forming against the Sixers' arena proposal" (Tweet). Retrieved February 9, 2023 – via Twitter.

- ^ Gammage, Jeff; Mikati, Massarah (December 15, 2022). "Chinatown residents loudly denounce Sixers arena proposal at contentious meeting". www.inquirer.com. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Chinatown Residents Share Concerns Over Proposed Sixers Arena in Center City". NBC10 Philadelphia. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ "Coalition created to fight construction of new Philadelphia 76ers arena near Chinatown". 6abc Philadelphia. January 9, 2023. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Walsh, Sean Collins (December 7, 2022). "How an under-the-radar parking garage bill sparked the first City Hall dust-up over the 76ers' arena proposal". www.inquirer.com. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Joyce, Jennifer (December 7, 2022). "Activists blocked bill that could have fast-tracked plan for new 76ers arena in Chinatown". FOX 29 Philadelphia. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ a b DiStefano, Joseph N. (August 1, 2022). "Proposed Sixers arena site would expand across Filbert Street". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved August 2, 2022.

- ^ a b Kinkead, Kevin (April 11, 2023). "Sixers Chief Communications Officer Says Howard Eskin is "Uninformed and Unimaginative"". Crossing Broad. Retrieved April 11, 2023.

- ^ a b "Joel Embiid, NFL Draft, Phillies and more!". 94.1 WIP. April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ a b c SanFilippo, Anthony (April 25, 2023). "Did Live Nation Subtly Pick a Side in the 76ers Stadium Debate on Howard Eskin's WIP Show?". Crossing Broad. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Moselle, Aaron (February 22, 2024). "Proposed Sixers arena could cost millions in lost tax revenue, new analysis finds". WHYY. Retrieved March 6, 2024.

- ^ Gammage, Jeff; Perez-Castells, Ariana (September 23, 2024). "Workers are on strike at the Linc, Citizens Bank Park, and Wells Fargo Center". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ "Hundreds march through Center City, Chinatown to protest the Sixers' arena proposal". WHYY. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ "Hundreds march through Center City, Chinatown to protest the Sixers' arena proposal". WHYY. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ a b "How will each city council member vote on the proposed 76ers arena?". PhillyVoice. September 25, 2024. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ D'Onofrio, Mike (March 12, 2024). "Readers back Comcast Spectacor over Sixers' arena in survey". Axios Philadelphia.

- ^ "'It isn't just Chinatown': Citywide poll shows little support for Sixers arena proposal". WHYY. Retrieved September 28, 2024.

- ^ D'Onofrio, Mike (October 1, 2024). "What Philadelphians are saying about the Sixers arena deal". Axios Philadelphia.

- ^ Ni, Henessis Umacata, Jasmine. "Chinatown activists opposed to 76ers arena legislation disrupt Phila. City Council meeting". www.thedp.com. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mitman, Hayden (December 5, 2024). "Amid 'productive negotiations,' City Council delays Sixers arena hearing". NBC10 Philadelphia. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Mitman, Hayden (December 11, 2024). "Outbursts lead City Council to postpone final committee meeting on Sixers arena". NBC10 Philadelphia. Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ Cann, Harrison (December 19, 2024). "At the buzzer: Sixers arena gets final Council approval on last day of session". City & State PA. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ "Philadelphia mayor strikes a deal with the 76ers to build a new arena downtown". AP News. September 18, 2024. Retrieved September 25, 2024.

- ^ a b "Philadelphia 76ers Announce Entrepreneur David Adelman to Lead New Arena Development; Pursuing Privately-Funded Development at Fashion District Philadelphia Site". NBA.com (Press release). Philadelphia 76ers. July 21, 2022. Retrieved July 21, 2022.

- ^ "Developer David Adelman is convinced the plan for 76 Place will succeed". September 30, 2022. Retrieved February 9, 2023.

- ^ Kelly, Tim. "Here's How Each Philadelphia City Council Member Voted on '76 Place'". OnPattison. Retrieved January 22, 2025.

- ^ Blumgart, Jake; Walsh, Sean Collins (January 12, 2025). "Sixers to remain in South Philly, abandoning plans to build a Center City arena". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved January 12, 2025.

- ^ Runes, Charmaine. "Here's how much the plan to build a Center City arena actually cost the city". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved January 22, 2025.