56 Beaver Street

| 56 Beaver Street | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Former names | Delmonico's Building |

| General information | |

| Type | Mixed use |

| Address | 56 Beaver Street, Manhattan, New York, US |

| Coordinates | 40°42′18″N 74°00′37″W / 40.70500°N 74.01028°W |

| Groundbreaking | 1890 |

| Opened | 1891 |

| Renovated | 1935, 1953, 1997 |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Brick, brownstone, architectural terracotta |

| Floor count | 8 |

| Floor area | 61,238 sq ft (5,689.2 m2) |

| Grounds | 9,150 sq ft (850 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | James Brown Lord |

| Developer | Delmonico's |

| Designated | February 13, 1996[1] |

| Reference no. | 1944[1] |

| Designated | February 20, 2007[2] |

| Part of | Wall Street Historic District |

| Reference no. | 07000063[2] |

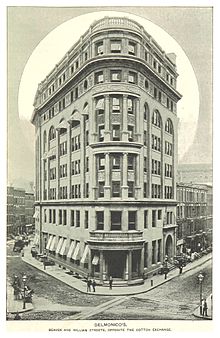

56 Beaver Street (also known as the Delmonico's Building and 2 South William Street) is a structure in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City, United States. Designed by James Brown Lord, the building was completed in 1891 as a location of the Delmonico's restaurant chain. The current building, commissioned by Delmonico's chief executive Charles Crist Delmonico, replaced Delmonico's first building on the site, which had been built in 1837. The building is a New York City designated landmark and a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District, a National Register of Historic Places district.

The eight-story structure, clad in brick, brownstone, architectural terracotta, occupies a triangular lot at the western corner of the five-pointed intersection of William, South William, and Beaver Streets. The facade is articulated into three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column, namely a two-story base, a five-story shaft, and a one-story capital. The building contains a curved corner with a portico that provides access to the restaurant on the lower stories. Inside, there is a restaurant space in the basement and first story, while the upper floors contain 40 condominiums.

The current building opened on July 7, 1891, with the restaurant at the base and top floor, as well as office space on the third through seventh floors. After 56 Beaver Street was sold to the American Merchant Marine Insurance Company in 1917, the restaurant was closed, and the building became an office structure known as the Merchant Marine House. The building was then sold twice in the 1920s before the City Bank-Farmers Trust Company foreclosed on the building. In 1926 Oscar Tucci purchased the lower level and first floor, then opened a restaurant. Tucci eventually acquired the entire building; his family continued to run the restaurant until the 1980s. The building's upper stories were renovated in the early 1980s. From 1982 to 1993, under a licensing agreement with the Tuccis, Ed Huber operated Delmonico's at 56 Beaver Street. Time Equities acquired the building in 1995; converting the upper stories into apartments; the lower stories operated yet again as a restaurant from 1998 to 2020. Delmonico's is scheduled to reopen in late 2023.

Site

56 Beaver Street is in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City.[3][4] The land lot is located at the western corner of the five-pointed intersection of William, South William, and Beaver Streets. It covers the eastern portion of the city block bounded by Broad Street to the west, Beaver Street to the north, and South William Street to the southeast. At the same intersection, the building abuts 1 William Street to the south, 15 William Street to the north, and 20 Exchange Place to the northeast. Other nearby structures include the Broad Exchange Building and 45 Broad Street to the northwest, as well as 1 Hanover Square to the southeast.[4]

The site covers 9,150 sq ft (850 m2), with a frontage of 150.9 ft (46.0 m) on Beaver Street and a depth of 149.5 ft (45.6 m).[4] The site originally measured 55.67 ft (17 m) wide along Beaver Street and 126 ft (38 m) wide along South William Street.[5][6] By the early 20th century, the building had been extended to cover 146 ft (45 m) on South William Street and 70 ft (21 m) on Beaver Street.[7][8]

Architecture

56 Beaver Street was designed by James Brown Lord for the Delmonico's restaurant chain.[9][10] Lord may have been hired to design 56 Beaver Street because he had designed a Delmonico's branch at 341 Broadway in 1886.[11][12] Architect and writer Robert A. M. Stern described the building as containing elements of the Richardsonian Romanesque and Renaissance Classicism styles.[13] The original design complemented the headquarters of the New York Cotton Exchange directly across William and South William streets, at the southeast corner of the intersection.[13][a]

Facade

56 Beaver Street contains a facade of orange Roman brick, brownstone, and beige terracotta. The facade is articulated into three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column, namely a base, shaft, and capital.[6][15] The two principal elevations on South William and Beaver streets are joined by a rounded corner on William Street, which is divided vertically into three bays. The Beaver Street elevation is divided into two wide bays and one narrow bay from west to east. The western portion of the South William Street elevation has two wide bays, while the eastern portion has three wide bays flanked by two narrow bays.[6]

Base

The lowest part of the two-story base contains a water table, which was originally made of brick and granite but was subsequently refaced in sandstone. Above the water table, the base is clad with Belleville brownstone.[6] The restaurant's main entrance is beneath a portico at the rounded corner on William Street.[16] Two Corinthian columns support a frieze with the name "Delmonico's" in all capital letters, above which runs a balustrade.[15][16] This portico was preserved from the previous building on the site.[17] Recessed behind the portico is the doorway, which is flanked by two columns. These columns, saved from the previous building, were reportedly imported from Pompeii,[17][18][19] and patrons touched these columns for good luck.[11] There is a marble cornice above the doorway, as well as wooden panels in the reveals of the doorway. The entrance itself is through a pair of wooden double doors with glass windows.[20]

On Beaver Street, a pink-granite stoop leads up to an archway, which leads to the building's residential (formerly office) stories. The archway occupies the westernmost bay of the facade and is surrounded by splayed jambs with classical motifs. The remainder of this bay is flanked by a pair of flat pilasters and is clad with stucco. The doors themselves are made of glass. Directly above the entrance are two windows on the second floor, which are flanked by reliefs that depict volutes. The address "56 Beaver Street" is printed on a plaque above those windows.[20] To the west are four four-story brownstone structures at 48-54 Beaver Street, which dates from the late 19th century. Part of the commercial space extends into these structures, and the lot at 54 Beaver Street.[15]

Near the western end of the South William Street elevation, a brownstone stoop leads up to the ground-level commercial space. The stoop is flanked by brownstone side walls with iron railings above them. The doorway contains stone carvings of Renaissance style motifs. The reveals of the doorway also contain wooden panels, and the door is topped by a transom bar and a window.[20] The westernmost two bays on South William Street contain entrance doorways.[20] The remaining bays contain simple window openings,[6][21] which have canopies above them.[20]

Upper stories

The third through seventh stories comprise the building's midsection.[16] The curved corner contains two stacked colonnades, each with four double-height engaged columns, on the third to sixth floors.[20][21][22] The curved corner's spandrel panels, above the windows on the third and fifth stories, contain foliate motifs. On the seventh story, the curved corner is decorated with brownstone panels that contain reliefs with arabesques.[20] On South William and Beaver Streets, a brick arch spans the third through sixth stories in each bay. The arches are surrounded by terracotta quoins, which contain reliefs with checkerboard patterns.[20][22] The remainders of both elevations are made of brick. Above these arches are terracotta panels with foliate motifs. A deep cornice with modillions runs above the seventh story.[20]

On all elevations, the eighth story is clad with brick. The windows on the eighth story are separated by pilasters with arabesques, above which is a small cornice.[21][20] There was formerly a balustrade above the cornice. The roof contains brick chimneys on the southwestern and northeastern corners, as well as a brick penthouse on the northwestern corner (near Beaver Street).[20]

Interior

56 Beaver Street was built with an iron and steel superstructure.[6] When the building was constructed, the basement and lowest two stories were used by the restaurant.[5] When the building opened, the main dining room on the first floor was open only to men.[22] The main dining room was decorated in white and gold.[17] This room contained a lunch counter at the rear of the room, near South William Street, as well as a bar and an oyster counter next to the lunch counter.[5] There was also a separate dining room for women, which was decorated in "carmine and white and gold" with a decorative fireplace.[17] The women's dining room took up half of the second story, while private dining rooms occupied the remainder of that story.[5][18] The basement was surrounded by a wall measuring 10 ft (3.0 m) thick. In the basement were a wine cellar, dynamos, elevator pumps, and staff dressing rooms.[5][23]

When the building was completed, the eighth story was used as a kitchen, with pneumatic tubes and hydraulic elevators running to the lower levels.[17][22] The pneumatic tubes would carry slips of paper, with guests' orders written on them, and the food was then sent down on the elevators. The kitchen itself was made of marble.[17] The third to seventh stories were rented out as offices.[18][22] In 1926, Oscar Tucci operated a speakeasy in the basement of the building. By 1935, Tucci owned the entire Delmonico building. Over the decade's of Tucci's ownership, he was operating the entire building as restaurant space. Since 1997, the building's upper stories have contained 37 apartments, which range from studio apartments covering 750 sq ft (70 m2) to two-bedroom units covering 1,500 sq ft (140 m2).[24]

History

Swiss brothers Pietro and Giovanni Delmonico opened a French cafe in 1827[25][26] at 23 William Street.[26][27] The brothers opened two more businesses in the surrounding neighborhood during the next decade.[27] After the 23 William Street building burned down in 1835 during the Great Fire of New York,[28] the Delmonico brothers constructed a building at the intersection of William, South William, and Beaver Streets in 1837. The three-story structure was known popularly as the Citadel because it had a rounded corner.[26][27] This structure also had cantilevered iron balconies on the second and third stories, as well as a colorful bar room and several smaller dining rooms.[29] It eventually became one of the most famous restaurants in New York City and was prominent nationally.[30][31] By the 1880s, the restaurant chain was extremely popular and had grown to four locations. In addition, many tall structures were being built in the Financial District, and the original branch was too small to accommodate the increased clientele.[32]

Delmonico family operation

Delmonico's chief executive Charles Crist Delmonico had bought two lots on South William Street, next to the Citadel, in 1889.[27][33][b] The same year, Delmonico hired Lord to design an eight-story building on the site of the Citadel.[12][34] The building would be the first significant non-residential structure designed by Lord.[11] In March 1890, The New York Times announced that the old Delmonico's Building had been demolished and that a new structure would be erected on the site.[5] Delmonico laid the cornerstone for the new building on July 10, 1890.[18][11] The new restaurant opened on July 7, 1891, almost exactly one year after the official groundbreaking.[17][18][11] Delmonico's Beaver Street branch was initially successful and was particularly known for its "daytime lunches".[9] In 1893, one newspaper described the restaurant as one of "the three great resorts for that human excrescence known as the moneyed dude" in Lower Manhattan.[35] The upper stories were leased to tenants such as New York, Ontario and Western Railway.[36]

With the closure of the restaurant's Broad Street branch in 1893,[18][37] the 56 Beaver Street location was Delmonico's only remaining outpost in Lower Manhattan;[11] the restaurant opened another location in Midtown Manhattan in the late 1890s.[28] Charles Delmonico died in 1901,[38] and his aunt Rosa Delmonico took over the restaurant's operation until her own death three years later.[11][39] As early as 1903, the City Real Property and Investing Company (which had bought the city block the prior year) contemplated demolishing the entire block and constructing a skyscraper on the site.[40] These plans never materialized, as City Real Investing sold most of the block in 1905.[41][42]

Meanwhile, following Rosa's death, Charles's sister Josephine Delmonico took over the Delmonico's chain.[11][43] The executor of Rosa's estate hired several accountants to investigate the finances of the two Delmonico's locations, finding that both locations "seem to be run entirely by the employees without any responsible head".[39] New York state appraisers found that she was heavily in debt and had guaranteed a $450,000 mortgage loan on 56 Beaver Street. Rosa Delmonico did not own the building, which was worth $750,000 at the time.[44][45] Delmonico's was incorporated in late 1908, with Josephine as the majority stockholder.[43] Various members of the Delmonico family held minority stakes in the corporation.[46] The same year, Title Insurance Company replaced the mortgage on the property with a new loan.[47] When Delmonico's debt started to increase in the 1910s, tensions between family members increased.[9][46] The restaurant's losses were exacerbated by the onset of World War I, which impacted global food supply chains.[46]

Use as insurance company building

In August 1917, the American Merchant Marine Insurance Company announced that it would buy the building for over $500,000 and use the structure as an "insurance center".[48][49] Cecil P. Stewart, head of Frank B. Hall & Company, represented the insurance company in the transaction.[50] The sale was finalized the following month; the new owner assumed a $425,000 mortgage on the property, and Robert R. Rainey was appointed as property manager.[51] Initially, the restaurant would continue operating on the lower floors, while the insurance offices would be on the upper floors.[6][50] The restaurant ultimately closed its 56 Beaver Street location on November 24, 1917,[52][53] and relocated to Broad Street;[54] the company continued to operate a branch in Midtown until 1923.[55]

The building was renamed the Merchant Marine House after the closure of the Delmonico's restaurant.[56] At the time, there were several financial exchanges nearby, including the Maritime Exchange, the Consolidated Stock Exchange of New York, the New York Cotton Exchange, and the New York Coffee and Sugar Exchange.[7] After 56 Beaver Street became the Merchant Marine House, its lower stories were divided into offices as well.[6] By early 1919, there were so many marine insurance companies at 56 Beaver Street that the American Merchant Marine Insurance Company purchased additional structures across the street to accommodate the additional demand.[57][58] The Insurance Company of North America (INA) purchased 56 Beaver Street in October 1920.[7][8] The sale represented a $400,000 profit for the American Merchant Marine Insurance Company.[8][59] The New York Times described the transaction as "the largest cash profit in any one realty deal in the neighborhood in recent years".[59]

During the 1920s and 1930s, the upper floors of 56 Beaver Street were being used as offices for ship insurance, legal offices, and other types of offices. INA owned the building until October 1929, when a syndicate of investors from New York City and Chicago bought 13 buildings on the city block for $6.5 million, including the fee position to the land under 56 Beaver Street.[60][61] INA then leased back the basement and the first through fourth stories.[62] The William and Beaver Corporation, a holding company representing the investors, received $3 million in financing for the buildings on the block in May 1930.[63][64] The financing consisted of a $2.25 million loan from the City Bank-Farmers Trust Company, which was merged with two other mortgage loans.[65] The Charles F. Noyes Company was hired as 56 Beaver Street's managing and renting agent in March 1933.[66][67] City Bank-Farmers Trust had foreclosed on the 13 buildings on the block by January 1934,[68][69] and they were placed for sale at a foreclosure auction that September.[70] City Bank-Farmers Trust ultimately took over the buildings in October 1934, bidding $3 million.[71][72]

Mid- to late 20th century

Tucci era

The restaurateur Oscar Tucci opened Oldelmonico Restaurant (also known as Oscar's Old Delmonico[73] or Oscar's Old Del Monico[74]) in the building in 1926 first as a speakeasy and small restaurant.[75] By December 1934, after the repeal of Prohibition, Brown, Wheelock, Harris & Co. had sold a restaurant and bar in the basement and first story to Oscar Tucci.[6][76] The restaurant was expanded to the second story in 1935 after becoming a popular eatery, and it was further enlarged in 1943 to the first story of 48–54 Beaver Street, which Oscar Tucci and City Bank-Farmers Trust Company owned.[6] A subsidiary of the bank, 44 Beaver Street Corporation, filed plans in 1944 for a 33-story structure to be built on the Delmonico's site.[77][78] Had this skyscraper been built, it would have been around 394 ft (120 m) tall, and it would have contained about 550,000 sq ft (51,000 m2) of space for offices, stores, and a restaurant.[77]

The building continued to be used as an office structure during the mid-20th century. In June 1953, the 44 Beaver Street Corporation (owned by Oscar Tucci) sold the structures at 48–56 Beaver Street to the 47 Beaver Street Corporation (owned by Mario Tucci & Mary Tucci).[79][80] This corporation's management represented Tucci, who hired architect John J. Regan the following year to draw up plans for renovating the lobby and the second through eighth floors. The redesigned lobby was to contain marble walls, fluorescent lights, new elevator cabs, and a rebuilt staircase.[81][82] Through the 1960s, the restaurant remained popular among those who worked in the Financial District.[83] The restaurant's guests included Richard Nixon, who frequently dined there before he was elected as U.S. president.[84]

Tucci operated the restaurant at the building until his death in 1969.[76] Mary Tucci and her brother Mario continued to run the restaurant into the 1970s.[85] The Tucci family ultimately licensed the restaurant after 1977, following the New York City fiscal crisis.[84] A New York Daily News article had described the building as "empty and dark, although two gas lamps at its entrance still burn with a ghostly flicker".[29] Three years later, the restaurant space was still vacant; Jennifer Dunning of The New York Times said the space was "so empty and deserted that it seems unhaunted even by ghosts".[86]

Huber lease

Ed Huber leased the building in 1981 and, after a renovation, reopened Delmonico's in 1982.[84] Huber used historical paragraphs to restore the original appearance of the restaurant.[87] Meanwhile, several Italian investors considered renovating the building into stores and residences.[84][87] They spent $6 million to convert the building into 30 residential condominiums. Due to a lack of demand for residential condominiums, the upper stories were instead rented out as office space.[87] In 1989, on the 150th anniversary of the original Delmonico's building on the site, the restaurant dedicated two dining rooms in the former wine cellar. The rooms were named after writers Charles Dickens and Mark Twain, who had both eaten at one of the previous Delmonico's locations.[84]

In an 18-month span from 1990 to 1991, four companies collectively vacated 30 percent of the building's space. During that time, the building's owners were unable to pay taxes for a year.[88] Around that time, business at Delmonico's had started to decline because numerous financial firms in the area had downsized.[89] The Delmonico's restaurant at the building's base closed in 1993,[90] largely because of the early 1990s recession.[91] By the mid-1990s, Tony Goldman and Washington Square Associates were considering buying 56 Beaver Street.[92]

Residential conversion and 21st century

In 1995, Time Equities Inc. and several partners bought the building for about $3 million; at the time, the restaurant space was empty and almost half of the office space was vacant.[93] Time Equities chairman Francis Greenburger said he had decided to buy the building half an hour after he saw it.[94] Greenburger renovated 56 Beaver Street, along with the nearby 47 West Street, into rental apartments.[95][96] The apartment conversion ultimately cost $3.7 million and was completed by 1997, at which point all of the apartments were leased.[24] Additionally, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) designated the Delmonico's Building as an official city landmark on February 13, 1996.[1][97] The building was one of over 20 structures in the Financial District that the LPC designated as landmarks during the 1990s.[98] By 1996, there were also plans to open a microbrewery in the Delmonico's space.[99][100] Greenburger had attempted to lease the restaurant space to Joe Quattrocchi, but the agreement fell through due to issues in obtaining a liquor license.[24]

Time Equities leased the space in 1997 to Bice Equities, which planned to open a 400-seat restaurant across the building's lowest two stories.[101] Morris Nathanson renovated the restaurant's interiors, adding 19th-century dark wood paneling and mid-20th-century murals.[102] In addition, a former bakery space in the basement was converted into a lounge.[103] The Delmonico's restaurant opened in the lower section of the building in May 1998.[102][104] The next year, four investors bought the building's restaurant space and formed Ocinomled Ltd. (named for a reverse spelling of the name "Delmonico").[105][106] In 2007, the building was designated as a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District,[107] a National Register of Historic Places district.[2]

The restaurant's four co-owners were involved in internal disputes with each other by the late 2010s, even as the restaurant remained popular.[105] The restaurant was forced to close temporarily in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, amid a lawsuit between the four co-owners.[106] A state judge ruled in favor of two of the co-owners, Ferdo and Omer Grgurev, in March 2021; the brothers planned to renovate the restaurant and reopen it in late 2021.[108] The building was damaged in September due to flooding caused by Hurricane Ida, and Time Equities was unable to repair the damage for several months.[109][110] Time Equities was in the process of evicting the Grgurev family by 2022, alleging that the Grgurevs had failed to pay $300,000 in rent during the pandemic.[109] Time Equities did not renew Ocinomled's lease when the lease expired in December 2022.[111] Dennis Turcinovic and Joseph Licul signed a 15-year lease for 14,393 square feet (1,337.2 m2) on the lower stories at the end of that month;[112] at the time, the restaurant was set to reopen in late 2023.[111][113] Oscar Tucci's grandson Max Tucci was hired that July as the restaurant's brand ambassador, while WAVE Design Studios redesigned the interior of the restaurant, adding five private dining rooms.[114] The Delmonico's at the building's base began hosting private events and groups in July[114][115] and formally reopened September 15, 2023.[116][117]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ The old Cotton Exchange building was demolished in 1923. It is not to be confused with One Hanover Square, which is one block south and also housed the Cotton Exchange.[14]

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 3, implies that Lord was hired for 56 Beaver Street in 1890, "four years" after the 341 Broadway commission.

Citations

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "National Register of Historic Places 2007 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2007. p. 65. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c "48 Beaver Street, 10004". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Amusements; the Theatrical Week". The New York Times. May 18, 1890. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 4.

- ^ a b c "Big Profit Taken on "Marine House"". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 106, no. 16. October 16, 1920. p. 543. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c "Marine House Brings Seller $400,000 Profit: Delmonico's Home, Bought by C. P. Stewart Few Years Ago, Now Owned by Insurance Co. of Nor. Amer". New-York Tribune. October 15, 1920. p. 19. ProQuest 576333988.

- ^ a b c Gray, Christopher (April 14, 1996). "Streetscapes/56 Beaver Street;On the Menu at 1891 Delmonico's: 40 Apartments". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 3.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 733.

- ^ a b Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, pp. 733–734.

- ^ "$3,000,000 New York Cotton Exchange Building to Be Built on Same Site as Present One; Structure Will Replace Downtown Landmark Erected Thirty-seven Years Ago--New Exchange Room Will Be at the Top of the Building". The New York Times. January 8, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2007, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Kitchen Is Where It Should Be". Buffalo Morning Express and Illustrated Buffalo Express. July 8, 1891. p. 6. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Delmonico's History". Steak Perfection. August 25, 2001. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 5.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2007, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1999, p. 734.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Rothstein, Mervyn (August 6, 1997). "A Restaurant May Once Again Fill Delmonico's". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Lee, Sunny (February 16, 2003). "Ten History Courses There Are Some Interesting Stories Behind NYC Restaurant Names - Just Ask Jimmy". New York Daily News. p. 17. ProQuest 305771949.

- ^ a b c Kludt, Amanda (June 29, 2011). "Remembering Delmonico's, New York's Original Restaurant". Eater NY. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 2.

- ^ a b Robinson, Walter German (March 26, 1904). "Famous New York Restaurants: the Social History of Dinner Giving, the Association of Famous Taverns and Magnificent Restaurants of to-day". Town and Country. No. 3019. p. 18. ProQuest 126832489.

- ^ a b Gayle, Margot (March 25, 1979). "New York's changing scene". Daily News. p. 352. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ Aaseng, Nathan (January 2001). Business Builders in Fast Food. The Oliver Press. pp. 8–10. ISBN 1-881508-58-7.

- ^ Hooker, Richard J (May 1981). "18 – Eating Out 1865–1900". Food and Drink in America: A History. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Co. ISBN 0-672-52681-6.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, pp. 2–3.

- ^ "Conveyances". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 43, no. 1109. June 15, 1889. p. 844. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Out Among the Builders". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 44, no. 1115. July 27, 1889. pp. 1049–1050.

- ^ "New York Restaurants.: No Chance to Go Hungry in the Big City. The Manhattan Elevated and Its 800,000 Daily Patrons. A Glance at the Brooklyn Bridge and Printing-house Square". Detroit Free Press. May 21, 1893. p. 16. ProQuest 562408911.

- ^ "Ontario and Western Election.; Two New Directors Chosen -- a Very Favorable Showing". The New York Times. September 29, 1892. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "To Be a Thing of the Past; Closing of Broad Street Delmonico's -- Since 1865 a favorite Resort for Brokers". The New York Times. April 15, 1893. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Death of C. C. Delmonico; He Was Manager of the Restaurants Bearing His Name. His Personal Popularity Was Pronounced Among a Wide Acquaintance -- History of the "Delmonico's" Establishments". The New York Times. September 21, 1901. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b "Receiver Sought for Delmonico's; Albert Thieriot, Executor of the Estate, Causes the Action". The New York Times. November 15, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Downtown Delmonico's May Go". New-York Tribune. February 17, 1903. p. 4. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field; Realty Companies Pay About $1,250,000 for Corner at Broad and Beaver Streets -- Buyers for Fine Dwellings -- Sales by Brokers and at Auction". The New York Times. August 17, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "Broad Street Plot Sold". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 76, no. 1953. August 19, 1905. p. 317. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "Delmonico's Now a Stock Company; Famous Restaurant Incorporated but There Will Be No Change in the Business". The New York Times. November 28, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Rich Guest Wed Hotel Maid; Manhattan Parlor Girl Will Be a Patron Where She Once Served". The New York Times. July 15, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Topics in New York: Heavy Claims Against the Estate of Rosa Delmonico Tattooing East Side Boys Children's Society Agents to Investigate a Practice Common Among the Poorer Classes". The Sun. July 16, 1906. p. 3. ProQuest 537219118.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, pp. 3–4.

- ^ "$450,000 Delmonico Loan; Mortgage on Beaver Street Property Given to the Title Insurance Company". The New York Times. November 29, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Newspaper Specials". The Wall Street Journal. August 21, 1917. p. 2. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Delmonico's to be Insurance Centre". The Sun. August 20, 1917. p. 10. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Downtown 'Del's' Sold". The Real Estate Record: Real estate record and builders' guide. Vol. 100, no. 2580. August 25, 1917. p. 239. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2022 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "Delmonico Building Sold". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 20, 1917. p. 21. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Old Delmonico's to Close". The Buffalo Enquirer. November 23, 1917. p. 5. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Old Delmonico's to Close". The Sun. November 24, 1917. p. 2. ProQuest 534822521.

- ^ "Will Rebuild Delmonico's: Downtown Branch to Reopen on Original Site". New-York Tribune. January 31, 1918. p. 14. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ Ford, James L. (May 27, 1923). "The House of Delmonico". New-York Tribune. p. A4. ProQuest 1114716430.

- ^ "The Passing of Delmonico's". The Wall Street Journal. November 17, 1917. p. 5. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Merchant Marine House; Nine-Story Structure to Cost $400,000 for Beaver Street". The New York Times. March 16, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Merchant Marine House Buys Realty". New York Herald. March 6, 1919. p. 11. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Big Profit Taken in Downtown Resale; The Merchant Marine House Sold to Insurance Company of North America". The New York Times. October 15, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "$6,500,000 Paid for Block In Wall St. Zone: New York and Chicago Syndicate Takes Beaver and William Street Triangle". New York Herald Tribune. October 18, 1929. p. 49. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1111676925.

- ^ "Beaver St. Corner in $7,000,000 Deal; Manhattan-Dearborn Corporation Buys Big Site in the Financial District". The New York Times. October 18, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Insurance Firm Takes Lease in Beaver Street: Firm Will Become Tenant in Property It Formerly Owned". New York Herald Tribune. June 12, 1930. p. 41. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113658288.

- ^ "Thirteen Buildings Downtown Mortgaged for $3,000,000". The New York Times. May 30, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "$3,000,000 Borrowed on Beaver St. Site: 30,000 Square Fool Triangle at William Street Is Covered by Mortgage". New York Herald Tribune. May 30, 1930. p. 27. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113703679.

- ^ "Downtown Real Estate Financed For $2,250,000: Brokers Arrange Mortgage on Beaver Street Corner; 1,200,000 Chelsea Loan". New York Herald Tribune. June 6, 1930. p. 37. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1113187688.

- ^ "Noyes Gets Management Of 100 More Buildings". New York Herald Tribune. March 12, 1933. p. C6. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1114627270.

- ^ "Agency Appointments; Many Large Buildings in Management of Noyes Company". The New York Times. March 19, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Yonkers Resident Buys Dwelling From Bank". New York Herald Tribune. January 12, 1934. p. 34. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1222204900.

- ^ "$3,000,000 Foreclosure Filed". The New York Times. January 12, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Site in Financial District To Be Sold at Auction: Lien of $3,311,230 Involved in Beaver St. Foreclosure". New York Herald Tribune. September 13, 1934. p. 38. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1221396957.

- ^ "Knickerbocker Village Begins Officially at 2". New York Herald Tribune. October 2, 1934. p. 32. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1243735119.

- ^ "Big Building Group Taken at Auction; City Bank, for $3,000,000, Bids In 13 Structures in Downtown Area". The New York Times. October 2, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "High Tax Values Held Realty Curb; Hoyt Tells Forum of Need for Apartments -- City's Growth Helped by New Airports". The New York Times. October 28, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Municipal Bond Womens' [sic] Club". Wall Street Journal. February 28, 1950. p. 5. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 131928467.

- ^ "Glamorous Dining Affair". Food & Beverage Magazine. January 2, 2023. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

- ^ a b "Oscar Tucci, 73, Operated Restaurant in Wall St. Area". The New York Times. June 7, 1969. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b "Plans Filed for 4 New Skyscrapers In Manhattan at $20,000,000 Cost; Will Rise in Downtown and Midtown Areas -- Costliest, $9,375,000, to Occupy 6th Ave. Site of Old Hippodrome". The New York Times. August 3, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "4 Skyscrapers Planned at Cost Of $23,628,000: Structures, 33 to 50 Stories High, Raise 6-Week Total of Major Projects to 23". New York Herald Tribune. August 3, 1945. p. 17. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1282936406.

- ^ "Transfers and Financing". New York Herald Tribune. June 17, 1953. p. 31. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1319942110.

- ^ "Manhattan Transfers". The New York Times. June 24, 1953. p. 44. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 112807372.

- ^ "Office Landmark to Be Modernized; Alterations Set for Building on Beaver Street Erected by the Delmonico Family". The New York Times. August 21, 1954. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Tucci Plans Modernizing Of Property in Beaver St". New York Herald Tribune. August 22, 1954. p. 5C. ISSN 1941-0646. ProQuest 1318566491.

- ^ "Too Many Mouths to Feed and Too Little Time for Lunch Pose Problem on Wall St". The New York Times. August 21, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Mangaliman, Jessie (January 6, 1989). "Delmonico's Looks Forward to Gay '90s". Newsday. p. 23. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Mulligan, Arthur (January 4, 1977). "City App-roaches Delmonico". Daily News. p. 23. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ Dunning, Jennifer (March 26, 1982). "A Diamond Jim Brady Eating-place Tour". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Postings; Revised 'Menu'". The New York Times. February 27, 1983. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ Bartlett, Sarah (August 9, 1991). "Tax Delinquencies in New York Rising Again". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Hays, Constance L. (June 23, 1990). "Shelter Finds Popularity By Doing Good Invisibly". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 16, 2022. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ "Quietly, Traders Went Bearish on Wall Street: New York: Financial industry's birthplace is a victim of obsolescence and decentralization". Los Angeles Times. August 1, 1994. p. D3. ProQuest 1973502936.

- ^ Eaton, Leslie; Barnes, Julian E. (October 12, 1998). "Affluent Buyers Show Signs Of Caution About Spending; Wall Street's Gloom Has New York Tense". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 7, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Slatin, Peter (July 30, 1995). "Housing Pioneers Scout the Downtown Frontier". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 17, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Rothstein, Mervyn (December 6, 1995). "Real Estate;The office building in lower Manhattan that housed Delmonico's changes hands for $3 million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Deutsch, Claudia H. (March 24, 1996). "Veterans of the 80's Return to the Wars". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 21, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Feldman, Amy (November 4, 1996). "Survival of the nicest". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 12, no. 45. p. 3. ProQuest 219184822.

- ^ Rothstein, Mervyn (December 11, 1996). "Real Estate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 18, 2021. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Louie, Elaine (February 15, 1996). "Currents;Ordering: A Landmark, Well Done". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Farago, Jason (January 11, 2018). "When Wall Street Was Unoccupied". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Deutsch, Claudia H. (May 26, 1996). "Commercial Property/The New York Information Technology Center;Leasing Real Space to Denizens of Cyberspace". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Givens, Ron (November 1, 1996). "Solo Brewery Did So-So; Now It's Chaos". Daily News. p. 226. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (November 5, 1997). "Off the Menu". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Fabricant, Florence (May 13, 1998). "Off the Menu". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 13, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Diehl, Lorraine (December 9, 2001). "The Intentional Tourist an at-home Vacation Spent Visiting Old Fami Liar Places Reveals the City's True Heart and Soul". New York Daily News. p. 2. ProQuest 305686694.

- ^ "Delmonico's resumes its standing in Manhattan". USA TODAY. May 15, 1998. p. 09D. ProQuest 408795518.

- ^ a b Swanson, David (April 6, 2018). "Amid Delmonico's Gilded Age Splendor, Diners Party Like It's 1899". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Warerkar, Tanay (August 25, 2020). "Historic NYC Steakhouse Delmonico's Future Hinges on an Internal Battle for Ownership". Eater NY. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ National Park Service 2007, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Warerkar, Tanay (March 26, 2021). "Iconic Steakhouse Delmonico's Plans to Reopen This Year After Resolving Lawsuit". Eater NY. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Adams, Erika (April 11, 2022). "Landlord Threatens to Evict NYC Institution Delmonico's From Its Historic Home". Eater NY. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ Modi, Priyanka (April 12, 2022). "Delmonico's in Landlord Dispute Over Hurricane Ida Damage". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on August 15, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ a b Orlow, Emma (January 20, 2023). "The Battle Over Reopening New York Institution Delmonico's". Eater NY. Archived from the original on January 24, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ Young, Celia (January 18, 2023). "Famed NYC Steakhouse Delmonico's Reopening This Fall". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (January 17, 2023). "A Naples Institution, L'Antica Pizzeria da Michele, Opens in the West Village". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 25, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ a b Lin, Sarah Belle (July 18, 2023). "Iconic NYC restaurant Delmonico's reopening in September with new chef and design, and new lease settling ownership battles". amNewYork. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ Gannon, Devin (July 20, 2023). "Historic NYC restaurant Delmonico's is reopening in the Financial District". 6sqft. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ "Delmonico's, piece of NYC history, reopens after 3-year pandemic closure". CBS New York. September 18, 2023. Archived from the original on September 24, 2023. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ Mavrek, Srecko (September 15, 2023). "New York City's iconic Delmonico's restaurant reopens its doors under Croatian ownership". Croatia Week. Archived from the original on March 3, 2024. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

Sources

- Delmonico's Building (PDF) (Report). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1999). New York 1880: Architecture and Urbanism in the Gilded Age. Monacelli Press. ISBN 978-1-58093-027-7. OCLC 40698653.

- Wall Street Historic District (PDF) (Report). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 20, 2007.

External links

Media related to Delmonico's Building at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Delmonico's Building at Wikimedia Commons