27th Texas Cavalry Regiment

| 27th Texas Cavalry Regiment Whitfield's Legion 1st Texas Legion 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion | |

|---|---|

John Wilkins Whitfield was the first colonel. | |

| Active | March 1862 – 4 May 1865 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Cavalry and Infantry |

| Size | Battalion, then Regiment |

| Nickname(s) | Whitfield's Legion, 1st Texas Legion, 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. John Wilkins Whitfield |

| Texas Cavalry Regiments (Confederate) | ||||

|

The 27th Texas Cavalry Regiment, at times also known as Whitfield's Legion or 1st Texas Legion or 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion, was a unit of mounted volunteers that fought in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. First organized as the 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion or Whitfield's Legion, the unit served dismounted at Pea Ridge and First Corinth. Additional companies from Texas were added and the unit was upgraded to the 27th Texas Cavalry Regiment or 1st Texas Legion later in 1862. Still dismounted, the unit fought at Iuka and Second Corinth. The regiment was remounted and fought at Holly Springs in 1862, Thompson's Station in 1863, and at Yazoo City, Atlanta, Franklin, and Third Murfreesboro in 1864. The regiment surrendered to Federal forces in May 1865 and its remaining soldiers were paroled.

Whitfield's Legion or 4th Texas Cavalry

Formation

The 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion, also known as Whitfield's Legion, began its existence as an independent cavalry company organized by Captain John Wilkins Whitfield in Lavaca County. The company marched to join Benjamin McCulloch's forces at Fort Smith, Arkansas, where it was combined with three independent cavalry companies from Texas and one from Arkansas to form a battalion, which was led by newly promoted Major Whitfield. The other Texas companies were led by Captains Edwin R. Hawkins from Hunt County, John H. Broocks from San Augustine County, and B. H. Norsworth from Jasper County. Normally a legion consists of infantry, cavalry, and artillery, but Whitfield's Legion was all cavalry.[1] It was reported to have a strength of 339 men at one point in late 1861.[2]

Pea Ridge

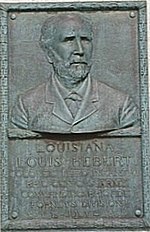

The 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion fought at the Battle of Pea Ridge on 7–8 March 1862. McCulloch's division was divided into a 3,000-man cavalry brigade led by James M. McIntosh and an oversized 5,700-strong infantry brigade under Louis Hébert. The battalion was dismounted and assigned to the infantry brigade along with the 3rd Louisiana, 4th Arkansas, 14th Arkansas, 15th Arkansas, 16th Arkansas, and 17th Arkansas Infantry Regiments, and the dismounted 1st Arkansas and 2nd Arkansas Mounted Rifles.[3] The first day began inauspiciously when Union skirmishers killed McCulloch while he was on a personal reconnaissance. McCulloch's staff notified McIntosh that he was in command, but erred by not sharing the news with the division's regimental commanders.[4][note 1]

McIntosh told his cavalry regiment commanders to wait for orders and impulsively moved forward to get the infantry attack rolling. McIntosh soon rode into a Federal volley and was killed. The commanders of the nearby units, including Whitfield, suspended the attack and withdrew. They hoped that Hébert, the third-in-command, would show up and give them orders.[5] By this time, Hébert was leading four infantry regiments into the dense woods to the east. McCulloch's staff went looking for Hébert, but they were unable to locate him, leading to a total collapse of the Confederate chain of command.[6] While Hébert's regiments fought alone, most of the division remained inert, waiting for orders. At about 3:30 pm, Albert Pike assumed command of McCulloch's division and led about 2,000 troops, including Whitfield's Legion, to join the rest of Earl Van Dorn's army which was east of Pea Ridge. A second group of 1,200 soldiers returned to the original Confederate camps, while a third group of 3,500 men remained on the battlefield before deciding to join Van Dorn.[7] After becoming separated from his troops, Hébert was later captured by Union soldiers.[8]

On the second day, Van Dorn inserted the 1st Arkansas Mounted Rifles, 16th and 17th Arkansas Infantry, and 4th Texas Cavalry into the center of the Confederate line near the Telegraph Road.[9] The Federals soon opened a very effective two hour bombardment of the Confederate positions.[10] Around mid-morning, Van Dorn found that his ordnance train was miles away; without the ability to get additional ammunition, he was forced to order a retreat.[11] On 25 March 1862, Van Dorn received orders to transfer his command to the east side of the Mississippi River. His troops marched from Van Buren, through Little Rock to Des Arc, Arkansas, where they boarded steamboats bound for Memphis, Tennessee. Hébert's brigade was the last to leave Arkansas, reaching Des Arc on 15 April and leaving for Memphis around 25 April.[12]

1st Texas Legion or 27th Texas Cavalry

Formation

Stephen B. Oates stated that Whitfield's unit had a strength of 1,007 men at the time of the transfer across the Mississippi.[13] The 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion was augmented by eight newly recruited companies from Texas and the Arkansas company was transferred to a regiment from that state. With 12 companies, the unit was renamed the 27th Texas Regiment or the 1st Texas Legion. Whitfield became colonel, Hawkins was promoted to lieutenant colonel, while Broocks, Cyrus K. Holman, and John T. Whitfield became majors.[1] In April 1862, Van Dorn's soldiers joined P. G. T. Beauregard's Confederate army at Corinth, Mississippi. The local water was scarce and soldiers drank from contaminated pools. Out of 80,000 Confederates in the army, 18,000 became sick.[14] On 29 April, Whitfield's Legion was assigned to the 2nd Brigade, Sterling Price's Division, Army of West Tennessee.[15] By the end of May 1862, Beauregard evacuated Corinth in the face of Henry Halleck's superior Union army and the Siege of Corinth came to an end.[16]

The table below lists each company and its recruiting area.[17] Soldiers who joined the regiment also came from Hopkins County and Morris County.[15]

| Company | Recruiting Area |

|---|---|

| A | Titus County |

| B | Hunt County[note 2] |

| C | San Augustine County |

| D | Lavaca County |

| E | Jasper County |

| F | Red River County |

| G | Lamar County |

| H | Red River County |

| I | Titus County |

| K | Arkansas |

| L | [note 3] |

| M | Jackson County, Lavaca County |

| N | Titus County |

Iuka and Corinth

At the Battle of Iuka on 19 September 1862, the 1st Texas Legion (dismounted) was assigned to Hébert's 2nd Brigade, Lewis Henry Little's 1st Division, Price's Army of the West.[18][note 4] The action occurred as a Union force under William Rosecrans bumped into Hébert's brigade south of Iuka.[19] Hébert deployed his 1,774-man brigade as follows. The 3rd Texas Cavalry Regiment (dismounted) was posted in front as a skirmisher screen, the 1st Texas Legion formed on the right flank, the combined 14th/17th Arkansas in the center, the 3rd Louisiana Infantry and the 3rd Missouri Battery on the left flank, and the 40th Mississippi Infantry Regiment in reserve. Little ordered Hebert's brigade to attack at about 5:15 pm with John Donelson Martin's 1,600-strong brigade in support. As the line went forward, the 3rd Texas reformed as the center unit while the Arkansans pulled back into reserve.[20]

The Confederates ran into a terrific blast of fire from Union soldiers on the ridge in front of them. Every one of Hébert's frontline units converged on the 11th Ohio Battery in the middle of the Union line.[21] After routing an Indiana regiment, the 1st Texas Legion began firing at the battery from the side.[22] The guns of the battery were captured after a brutal fight that cost the 1st Texas Legion, 3rd Texas, and 3rd Louisiana about 100 casualties each. All three regimental commanders were wounded, with Whitfield shot in the shoulder. The successful Confederate drive stalled when their division commander Little was killed and the coming of evening led to confusion.[23] A Federal attack briefly pushed the 1st Texas Legion off the ridge, but the Texans retook it, and with darkness the fighting finally sputtered out.[24]

At the Second Battle of Corinth on 3–4 October 1862, the 1st Texas Legion (dismounted) was part of W. Bruce Colbert's brigade, Hébert's division, Sterling Price's corps.[25] On 3 October, Colbert's brigade was in reserve behind Hebert's three frontline brigades during the mid-morning attack,[26] and it was still in reserve at 3:30 pm.[27] On 4 October, Van Dorn expected Hébert's division to attack at dawn, as ordered. However, Hébert belatedly reported himself sick at headquarters and was replaced by Martin E. Green.[28] In the confusion, Green's division did not attack until 10:00 am.[29] Green's two right-hand brigades burst through the Union defenders and seized Battery Powell, but took heavy losses.[30] The two left-hand brigades, which included Colbert's, ran into tougher opposition. After 45 minutes of fighting, Colbert's soldiers were repulsed with serious losses. The Union troops captured 132 men from Colbert's brigade.[31] At Corinth, the 1st Texas Legion lost 3 killed, 17 wounded, and 75 captured.[32]

Remounted

On 23 October 1862, the 1st Texas Legion or 27th Texas Cavalry was assigned to a brigade that also included the 3rd Texas Cavalry, 6th Texas Cavalry, and 9th Texas Cavalry Regiments and Whitfield was appointed to command the brigade. In the late fall of 1862, horses arrived from Texas and the entire brigade was remounted as cavalry. When a Union army under Ulysses S. Grant invaded Mississippi from the north, the Confederates attempted to strike at its Holly Springs supply base. On 16 December 1862, Van Dorn led 3,500 Confederate cavalry from Grenada, Mississippi.[34] Whitfield's cavalry brigade, including the 27th Texas Cavalry, participated in the raid.[35] The Holly Springs Raid was a huge success on 20 December when Van Dorn's troopers captured 1,500 Union soldiers and put Grant's supplies to the torch.[34]

Whitfield's cavalry brigade participated in the Battle of Thompson's Station[35] on 4–5 March 1863. The Union army sent a reinforced infantry brigade led by John Coburn on a reconnaissance toward Columbia, Tennessee. Coburn's force was surrounded by Van Dorn's two cavalry divisions and, after running out of ammunition, forced to surrender. The Federals admitted losing 1,700 men, mostly prisoners, while the Confederates lost only 300.[36] Whitfield's Brigade was also involved in a skirmish near Franklin on 10 April 1863. Whitfield received promotion to brigadier general in May 1863,[35] with Hawkins replacing him as colonel of the 27th Texas Cavalry until the end of the war.[15] The brigade returned to Mississippi during the Vicksburg campaign where it was engaged in peripheral actions.[35] On 4 June 1863, there were 123 officers and 1,354 men present for duty in the brigade and Lieutenant Colonel Broocks led the 1st Texas Legion.[37] Whitfield became ill and in mid-December 1863 Lawrence Sullivan Ross assumed command of the Texas cavalry brigade.[35]

Ross' Brigade was involved in a series of clashes with a Union force that was operating along the Yazoo River in February and March 1864. On 5 March 1864, a brigade of Tennessee cavalry under Robert V. Richardson joined Ross' troops in an attack on the Federals in the Battle of Yazoo City. When the 11th Illinois Infantry, 47th US Colored Infantry, and 3rd US Colored Cavalry refused to surrender, the Confederates withdrew. They sustained 64 casualties and inflicted 183 losses on the Federals.[38] On 15 May, the 27th Texas Cavalry joined the Army of Tennessee in the Atlanta campaign.[15] During the campaign it served in Ross' Brigade and William Hicks Jackson's Division. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War referred to the unit as the 1st Texas Legion under the command of Hawkins.[39]

Atlanta campaign

Ross' Brigade was under fire for 112 days and fought in 86 actions during the Atlanta campaign.[35] On 17 May 1864, the brigade covered the evacuation of Rome, Georgia.[40] A few days later, Ross reported that Union forces under the overall command of William T. Sherman crossed the Etowah River at Wooley's bridge west of Kingston.[41] On 22 May, Ross notified his army commander Joseph E. Johnston that Federal troops were crossing the Etowah in strength. Johnston therefore shifted his troops to counter this threat and the result was the Battle of New Hope Church three days later.[42] Soon after the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain on 27 June, a Union infantry division drove Ross' Brigade from the point where the Sandtown Road crossed Olley's Creek and gained a foothold.[43] On 29 July, Edward M. McCook's Union cavalry division raided behind Confederate lines, burning 500 wagons and damaging the railroad at Lovejoy's Station. Pursued by Confederate cavalry, McCook was surrounded near Newnan. McCook's horsemen overran Ross' Brigade, capturing Ross, but other Confederate forces soon closed around the Union raiders. They freed Ross and other prisoners, then inflicted 600 casualties on McCook's troopers before they could escape.[44]

On the evening of 18 August 1864, 4,700 Union cavalry led by Hugh Judson Kilpatrick set out on a raid. Because Joseph Wheeler took 6,000 Confederate cavalry to raid Sherman's railroad supply line, only 400 horsemen under Ross were immediately available to oppose the Union raiders. Nevertheless, Ross' Brigade managed to slow Kilpatrick's advance by setting ambushes. Though the new Confederate army commander John Bell Hood sent reinforcements, they went astray, so that the Union raiders chased Ross out of Jonesborough. It soon began to rain, preventing the Union horsemen from properly wrecking the railroad on 19 August. After marching to Lovejoy's Station on 20 August, Kilpatrick's cavalry got caught between a cavalry-infantry force in front and Ross' Brigade in their rear. In the only successful saber charge during the campaign, the Union raiders simply galloped through Ross' outnumbered troopers, capturing a howitzer and the colors of the 3rd Texas Cavalry. On 22 August, Kilpatrick's command reached Union lines at Decatur after sustaining 237 casualties and inflicting a similar number. The raid was a failure because the Confederates quickly got the railroad operating again.[45]

After his cavalry failed, Sherman moved the bulk of his army to break the railroad into Atlanta. On 30 August 1864 near Jonesboro, major Union units forced a crossing of the Flint River against the opposition of the cavalry brigades of Ross and Frank Crawford Armstrong.[46] Right before the Battle of Jonesborough on 31 August, Ross reported that two or three additional Union corps were moving toward Jonesborough.[47] That day, two Union corps occupied a section of the railroad near Rough and Ready, essentially dooming the Confederate defense of Atlanta.[48]

Nashville campaign

The 27th Texas Cavalry participated in operations in northern Georgia and northern Alabama from 29 September to 3 November 1864. The regiment took part in the Franklin–Nashville campaign from 22 November to 25 December.[15] On the evening of 28 November, before the Battle of Spring Hill, Ross' Brigade got behind a Union cavalry brigade at Hardison's Mill on the Duck River. The 1,500 Federal cavalry were able to break out by charging past Ross' troops, losing only about 30 men.[49] The next day, Nathan Bedford Forest sent Ross' 600 Texans to pursue James H. Wilson's Union cavalry toward Franklin while he led the rest of his command to Spring Hill, completely fooling Wilson.[50] That night, Ross' men burned the bridge and depot at Thompson's Station.[51] At 2:00 am on 30 November, Ross returned to Thompson's Station where his troops burned 39 wagons before withdrawing. Later that morning, faced with solid columns of retreating Federal infantry, Ross' Brigade was unable to attack the Union wagon train.[52] During the Battle of Franklin, Forrest attempted to get around the Union eastern flank. Ross' Brigade crossed the Harpeth River at Hughes Ford but soon ran into superior numbers of Federal cavalry and was compelled to fall back.[53]

The 27th Texas Cavalry missed the Battle of Nashville because Hood ordered Forrest to take the divisions of Jackson and Abraham Buford to Murfreesboro. Hood hoped that by harassing its 8,000-man Federal garrison, he would compel the Union army of George H. Thomas at Nashville to commit a blunder.[54] At the Third Battle of Murfreesboro on 7 December 1864, Forrest set a trap for a 3,325-man Union force under Robert H. Milroy. While the Federal infantry made a frontal attack on Forrest's infantry, Jackson's cavalry would attack them from the rear. In the event, the Confederate infantry ran away so quickly that the Union force captured two guns and 207 men before Jackson's horsemen could intervene.[55]

Hood's army was defeated at Nashville and forced to retreat. On 19 December 1864, Forrest took command of the rearguard comprising 3,000 cavalry and 1,600 infantry.[56] On 25 December, Forrest ambushed the pursuing Federal cavalry at Anthony's Hill, routing two brigades and capturing one cannon. The next day, Forrest again set an ambush at Sugar Creek, with Confederate infantry deployed in the center and the cavalry of Ross and Armstrong on the flanks. In this action, 150 Union cavalrymen were killed and wounded, and 12 captured. This ended the Federal pursuit of Hood's army, except for a token force of 500 cavalry. On 28 December, the last elements of Hood's army escaped across the Tennessee River.[57] The 27th Texas Cavalry was stationed near Iuka when all Confederate troops in the department formally surrendered on 4 May 1865. Later that month, the soldiers were paroled at Corinth and Meridian, Mississippi, and the regiment ceased to exist.[15]

See also

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ Authors Shea and Hess always refer to the unit as the 4th Texas Cavalry Battalion.

- ^ Williams' list omitted B Company, but Hunt County contributed one of the original 5 companies according to Cutrer (1995).

- ^ Williams' list omitted L Company. Since the regiment had 12 companies and N Company is listed, it is possible that L was skipped. Note that J was always skipped.

- ^ Cozzens always refers to the 1st Texas Legion.

- Citations

- ^ a b Cutrer 1995.

- ^ Oates 1994, p. 28.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, p. 23.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 116–118.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 142–146.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, p. 149.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, p. 224.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 231–233.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, p. 239.

- ^ Shea & Hess 1992, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Oates 1994, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e f Hathcock 2011.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 23.

- ^ a b Williams 2020.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 325.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 78.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 86–88.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 88.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 90.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 106–108.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 327.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 167.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 203.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 235.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, p. 237.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 240–245.

- ^ Cozzens 1997, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Official Records 1886, p. 382.

- ^ Official Records 1891, p. 331.

- ^ a b Atkinson 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Benner 2017.

- ^ Boatner 1959, p. 838.

- ^ Official Records 1889, p. 947.

- ^ Dobak 2011, pp. 200–202.

- ^ Battles & Leaders 1987, p. 292.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 196.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 205.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 219.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 317.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 437–438.

- ^ Castel 1992, pp. 471–474.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 494.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 498.

- ^ Castel 1992, p. 504.

- ^ Sword 1992, p. 105.

- ^ Sword 1992, p. 117.

- ^ Sword 1992, p. 145.

- ^ Sword 1992, p. 151.

- ^ Sword 1992, p. 241.

- ^ Sword 1992, pp. 282–284.

- ^ Sword 1992, pp. 296–298.

- ^ Sword 1992, p. 407.

- ^ Sword 1992, pp. 417–421.

References

- Atkinson, Matt (April 15, 2018). "Van Dorn's Raid". Center for Study of Southern Culture: Mississippi Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 29, 2021.

- Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Vol. 4. Secaucus, N.J.: Castle. 1987 [1883]. ISBN 0-89009-572-8.

- Benner, Judith Ann (June 22, 2017). "ROSS'S BRIGADE, C.S.A." Texas State Historical Association: Handbook of Texas. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Castel, Albert E. (1992). Decision in the West: The Atlanta Campaign of 1864. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0562-2.

- Cozzens, Peter (1997). The Darkest Days of the War: The Battles of Iuka and Corinth. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2320-1.

- Cutrer, Thomas W.: WHITFIELD'S LEGION from the Handbook of Texas Online (October 1, 1995). Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- Dobak, William A. (2011). "Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops 1862–1867" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. pp. 200–202. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- Hathcock, James A.: TWENTY-SEVENTH TEXAS CAVALRY from the Handbook of Texas Online (April 7, 2011). Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- Oates, Stephen B. (1994) [1961]. Confederate Cavalry West of the River (PhD). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-71152-2.

- "The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies Volume XVII Part I". Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1886. p. 382. Retrieved August 30, 2021. (Select Volume XVII Part I and scroll to page 382.)

- "The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Volume XXIV Part III". Washington, D.C.: United States War Dept. 1889. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- "The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Vol. XXXII Part I". Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. 1891. p. 331. Retrieved September 1, 2021. (Select Volume XXXII Part I and scroll to page 331.)

- Shea, William L.; Hess, Earl J. (1992). Pea Ridge: Civil War Campaign in the West. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4669-4.

- Sword, Wiley (1992). The Confederacy's Last Hurrah: Spring Hill, Franklin, and Nashville. New York, N.Y.: University Press of Kansas for HarperCollins. ISBN 0-7006-0650-5.

- Williams, James E. (2020). "A Revised List of Texas Confederate Regiments, Battalions, Field Officers, and Local Designations". jamesewilliams.tripod. Retrieved August 27, 2021.