1990s in history

1990s in history refers to significant events in the 1990s.

World events

End of the Cold War

The post–Cold War era is a period of history that follows the end of the Cold War, which represents history after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991. This period saw many former Soviet republics become sovereign nations, as well as the introduction of market economies in eastern Europe. This period also marked the United States becoming the world's sole superpower.

Relative to the Cold War, the period is characterized by stabilization and disarmament. Both the United States and Russia significantly reduced their nuclear stockpiles. The former Eastern Bloc became democratic and was integrated into the world economy. Most of former Soviet satellites and three former Baltic Republics were integrated into the European Union and NATO. In the first two decades of the period, NATO underwent three series of enlargement and France reintegrated into the NATO command.

Russia formed the Collective Security Treaty Organization to replace the dissolved Warsaw Pact, established a strategic partnership with China and several other countries, and entered the non-military organizations SCO and BRICS. Both latter organizations included China, which is a fast rising power. Reacting to the rise of China, the Obama administration rebalanced strategic forces to the Asia-Pacific region.

Major crises of the period included the Gulf War, Yugoslav Wars, the First and Second Congo Wars, First and Second Chechen War, September 11 attacks, War in Afghanistan (2001–2021), Iraq War, Russo-Georgian War, the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War and the ongoing Israel-Hamas war. It has been argued that the war on terror—whose wars in some ways connect to some of the previously mentioned wars in the Middle East—is the latest and most recent global conflict of the post-Cold War era.Yugoslav Wars

Officers of the Slovenian National Police Force escort captured soldiers of the Yugoslav People's Army back to their unit during the Slovenian War of Independence; a destroyed M-84 tank during the Battle of Vukovar; anti-tank missile installations of the Serbia-controlled Yugoslav People's Army during the siege of Dubrovnik; reburial of victims of the 1995 Srebrenica massacre in 2010; an armoured vehicle of the United Nations Protection Force near the Assembly building during the siege of Sarajevo.

The Yugoslav Wars were a series of separate but related[1][2][3] ethnic conflicts, wars of independence, and insurgencies that took place from 1991 to 2001[A 1] in what had been the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFR Yugoslavia). The conflicts both led up to and resulted from the breakup of Yugoslavia, which began in mid-1991, into six independent countries matching the six entities known as republics that had previously constituted Yugoslavia: Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, and Macedonia (now called North Macedonia). SFR Yugoslavia's constituent republics declared independence due to unresolved tensions between ethnic minorities in the new countries, which fueled the wars. While most of the conflicts ended through peace accords that involved full international recognition of new states, they resulted in a massive number of deaths as well as severe economic damage to the region.

During the initial stages of the breakup of Yugoslavia, the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) sought to preserve the unity of the Yugoslav nation by eradicating all republic governments. However, it increasingly came under the influence of Slobodan Milošević, whose government invoked Serbian nationalism as an ideological replacement for the weakening communist system. As a result, the JNA began to lose Slovenes, Croats, Kosovar Albanians, Bosniaks, and Macedonians, and effectively became a fighting force of only Serbs and Montenegrins.[5] According to a 1994 report by the United Nations (UN), the Serb side did not aim to restore Yugoslavia; instead, it aimed to create a "Greater Serbia" from parts of Croatia and Bosnia.[6] Other irredentist movements have also been brought into connection with the Yugoslav Wars, such as "Greater Albania" (from Kosovo, idea abandoned following international diplomacy)[7][8][9][10][11] and "Greater Croatia" (from parts of Herzegovina, abandoned in 1994 with the Washington Agreement).[12][13][14][15][16]

Often described as one of Europe's deadliest armed conflicts since World War II, the Yugoslav Wars were marked by many war crimes, including genocide, crimes against humanity, ethnic cleansing, massacres, and mass wartime rape. The Bosnian genocide was the first European wartime event to be formally classified as genocidal in character since the military campaigns of Nazi Germany, and many of the key individuals who perpetrated it were subsequently charged with war crimes;[17] the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) was established by the UN in The Hague, Netherlands, to prosecute all individuals who had committed war crimes during the conflicts.[18] According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, the Yugoslav Wars resulted in the deaths of 140,000 people,[19] while the Humanitarian Law Center estimates at least 130,000 casualties.[20] Over their decade-long duration, the conflicts resulted in major refugee and humanitarian crises.[21][22][23]

In 2006 the Central European free trade agreement (CEFTA) was expanded to include many of the previous Yugoslav republics, in order to show that despite the political conflicts economic cooperation was still possible. CEFTA went into full effect by the end of 2007.[24]Gulf War

| Gulf War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Over 950,000 soldiers 3,113 tanks 1,800 aircraft 2,200 artillery pieces |

1,000,000+ soldiers (~600,000 in Kuwait) 5,500 tanks 700+ aircraft 3,000 artillery systems[29] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Total: 13,488 Coalition: |

Total: 175,000–300,000+ Iraqi: 20,000–50,000 killed[42][43] 75,000+ wounded[30] 80,000–175,000 captured[42][44][45] 3,300 tanks destroyed[42] 2,100 APCs destroyed[42] 2,200 artillery pieces destroyed[42] 110 aircraft destroyed[citation needed] 137 aircraft flown to Iran to escape destruction[46][47] 19 ships sunk, 6 damaged[citation needed] | ||||||||

|

Kuwaiti civilian losses: Over 1,000 killed[48] 600 missing people[49] Iraqi civilian losses: 3,664 killed directly[50] Total Iraqi losses (including 1991 Iraqi uprisings): 142,500–206,000 deaths (According to Medact)[a][51] Other civilian losses: 75 killed in Israel and Saudi Arabia, 309 injured | |||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Ba'athism |

|---|

|

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Political offices

Rise to power Presidency Desposition Elections and referendums  |

||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 43rd Vice President of the United States Vice presidential campaigns 41st President of the United States Tenure Policies Appointments Presidential campaigns  |

||

The Gulf War was an armed conflict between Iraq and a 42-country coalition led by the United States. The coalition's efforts against Iraq were carried out in two key phases: Operation Desert Shield, which marked the military buildup from August 1990 to January 1991; and Operation Desert Storm, which began with the aerial bombing campaign against Iraq on 17 January 1991 and came to a close with the American-led liberation of Kuwait on 28 February 1991.

On 2 August 1990, Iraq, governed by Saddam Hussein, invaded neighboring Kuwait and fully occupied the country within two days. The invasion was primarily over disputes regarding Kuwait's alleged slant drilling in Iraq's Rumaila oil field, as well as to cancel Iraq's large debt to Kuwait from the recently ended Iran-Iraq War. After Iraq briefly occupied Kuwait under a rump puppet government known as the Republic of Kuwait, it split Kuwait's sovereign territory into the Saddamiyat al-Mitla' District in the north, which was absorbed into Iraq's existing Basra Governorate, and the Kuwait Governorate in the south, which became Iraq's 19th governorate.

The invasion of Kuwait was met with immediate international condemnation, including the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 660, which demanded Iraq's immediate withdrawal from Kuwait, and the imposition of comprehensive international sanctions against Iraq with the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 661. British prime minister Margaret Thatcher and U.S. president George H. W. Bush deployed troops and equipment into Saudi Arabia and urged other countries to send their own forces. Many countries joined the American-led coalition forming the largest military alliance since World War II. The bulk of the coalition's military power was from the United States, with Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, and Egypt as the largest lead-up contributors, in that order.

United Nations Security Council Resolution 678, adopted on 29 November 1990, gave Iraq an ultimatum, expiring on 15 January 1991, to implement Resolution 660 and withdraw from Kuwait, with member-states empowered to use "all necessary means" to force Iraq's compliance. Initial efforts to dislodge the Iraqis from Kuwait began with aerial and naval bombardment of Iraq on 17 January, which continued for five weeks. As the Iraqi military struggled against the coalition attacks, Iraq fired missiles at Israel to provoke an Israeli military response, with the expectation that such a response would lead to the withdrawal of several Muslim-majority countries from the coalition. The provocation was unsuccessful; Israel did not retaliate and Iraq continued to remain at odds with most Muslim-majority countries. Iraqi missile barrages against coalition targets in Saudi Arabia were also largely unsuccessful, and on 24 February 1991, the coalition launched a major ground assault into Iraqi-occupied Kuwait. The offensive was a decisive victory for the coalition, who liberated Kuwait and promptly began to advance past the Iraq–Kuwait border into Iraqi territory. A hundred hours after the beginning of the ground campaign, the coalition ceased its advance into Iraq and declared a ceasefire. Aerial and ground combat was confined to Iraq, Kuwait, and areas straddling the Iraq–Saudi Arabia border.

The conflict marked the introduction of live news broadcasts from the front lines of the battle, principally by the American network CNN. It has also earned the nickname Video Game War, after the daily broadcast of images from cameras onboard American military aircraft during Operation Desert Storm. The Gulf War has also gained fame for some of the largest tank battles in American military history: the Battle of Medina Ridge, the Battle of Norfolk, and the Battle of 73 Easting.Science and technology

Rise of the World Wide Web

During the first decade or so of the public Internet, the immense changes it would eventually enable in the 2000s were still nascent. In terms of providing context for this period, mobile cellular devices ("smartphones" and other cellular devices) which today provide near-universal access, were used for business and not a routine household item owned by parents and children worldwide. Social media in the modern sense had yet to come into existence, laptops were bulky and most households did not have computers. Data rates were slow and most people lacked means to video or digitize video; media storage was transitioning slowly from analog tape to digital optical discs (DVD and to an extent still, floppy disc to CD). Enabling technologies used from the early 2000s such as PHP, modern JavaScript and Java, technologies such as AJAX, HTML 4 (and its emphasis on CSS), and various software frameworks, which enabled and simplified speed of web development, largely awaited invention and their eventual widespread adoption.

The Internet was widely used for mailing lists, emails, creating and distributing maps with tools like MapQuest, e-commerce and early popular online shopping (Amazon and eBay for example), online forums and bulletin boards, and personal websites and blogs, and use was growing rapidly, but by more modern standards, the systems used were static and lacked widespread social engagement. It awaited a number of events in the early 2000s to change from a communications technology to gradually develop into a key part of global society's infrastructure.

Typical design elements of these "Web 1.0" era websites included:[56] Static pages instead of dynamic HTML;[57] content served from filesystems instead of relational databases; pages built using Server Side Includes or CGI instead of a web application written in a dynamic programming language; HTML 3.2-era structures such as frames and tables to create page layouts; online guestbooks; overuse of GIF buttons and similar small graphics promoting particular items;[58] and HTML forms sent via email. (Support for server side scripting was rare on shared servers so the usual feedback mechanism was via email, using mailto forms and their email program.[59]

During the period 1997 to 2001, the first speculative investment bubble related to the Internet took place, in which "dot-com" companies (referring to the ".com" top level domain used by businesses) were propelled to exceedingly high valuations as investors rapidly stoked stock values, followed by a market crash; the first dot-com bubble. However this only temporarily slowed enthusiasm and growth, which quickly recovered and continued to grow.

The history of the World Wide Web up to around 2004 was retrospectively named and described by some as "Web 1.0".[60]

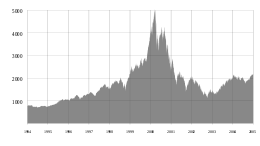

The dot-com bubble (or dot-com boom) was a stock market bubble that ballooned during the late-1990s and peaked on Friday, March 10, 2000. This period of market growth coincided with the widespread adoption of the World Wide Web and the Internet, resulting in a dispensation of available venture capital and the rapid growth of valuations in new dot-com startups. Between 1995 and its peak in March 2000, investments in the NASDAQ composite stock market index rose by 800%, only to fall 78% from its peak by October 2002, giving up all its gains during the bubble.

During the dot-com crash, many online shopping companies, notably Pets.com, Webvan, and Boo.com, as well as several communication companies, such as Worldcom, NorthPoint Communications, and Global Crossing, failed and shut down.[61][62] Others, like Lastminute.com, MP3.com and PeopleSound remained through its sale and buyers acquisition. Larger companies like Amazon and Cisco Systems lost large portions of their market capitalization, with Cisco losing 80% of its stock value.[62][63]Major changes in personal computers

Windows 95 is a consumer-oriented operating system developed by Microsoft and the first of its Windows 9x family of operating systems, released to manufacturing on July 14, 1995, and generally to retail on August 24, 1995. Windows 95 merged Microsoft's formerly separate MS-DOS and Microsoft Windows products, and featured significant improvements over its predecessor, most notably in the graphical user interface (GUI) and in its simplified "plug-and-play" features. There were also major changes made to the core components of the operating system, such as moving from a mainly cooperatively multitasked 16-bit architecture of its predecessor Windows 3.1 to a 32-bit preemptive multitasking architecture.[b]

Windows 95 introduced numerous functions and features that were featured in later Windows versions, and continue in modern variations to this day, such as the taskbar, notification area, and the "Start" button which summons the Start menu.[64][65] Accompanied by an extensive marketing campaign[64] that generated much prerelease hype,[66] it was a major success[67] and is considered to be one of the biggest and most important products in the personal computing industry.[68][69] Three years after its introduction, Windows 95 was followed by Windows 98. Microsoft ended mainstream support for Windows 95 on December 31, 2000. Like Windows NT 3.51, which was released shortly before, Windows 95 received only one year of extended support, ending on December 31, 2001.Africa

Congo Wars

The First Congo War,[c] also known as Africa's First World War,[70] was a civil and international military conflict that lasted from 24 October 1996 to 16 May 1997, primarily taking place in Zaire (which was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo during the conflict). The war resulted in the overthrow of Zairean President Mobutu Sese Seko, who was replaced by rebel leader Laurent-Désiré Kabila. This conflict, which also involved multiple neighboring countries, set the stage for the Second Congo War (1998–2003) due to tensions between Kabila and his former allies.

By 1996, Zaire was in a state of political and economic collapse, exacerbated by long-standing internal strife and the destabilizing effects of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, which had led to the influx of refugees and militant groups into the country. The Zairean government under Mobutu, weakened by years of dictatorship and corruption, was unable to maintain control,[71][72] and the army had deteriorated significantly.[73][74] With Mobutu terminally ill and unable to manage his fractured government, loyalty to his regime waned. The end of the Cold War further reduced Mobutu's international support, leaving his regime politically and financially bankrupt.[75][76]

The war began when Rwanda invaded eastern Zaire in 1996 to target rebel groups that had sought refuge there. This invasion expanded as Uganda, Burundi, Angola, and Eritrea joined, while an anti-Mobutu coalition of Congolese rebels formed.[71] Despite efforts to resist, Mobutu's regime quickly collapsed,[77] with widespread violence and ethnic killings occurring throughout the conflict.[78] Hundreds of thousands died as the government forces, supported by Sudanese militias, were overwhelmed.

After Mobutu's ousting, Kabila's government renamed the country the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, his regime remained unstable, as he sought to distance himself from his former Rwandan and Ugandan backers. In response, Kabila expelled foreign troops and forged alliances with regional powers such as Angola, Zimbabwe, and Namibia.[79] These actions prompted a second invasion from Rwanda and Uganda, triggering the Second Congo War in 1998. Some historians and analysts view the First and Second Congo Wars as part of a continuous conflict with lasting effects that continue to affect the region today.[80][81][[File:1; |thumb|]]

The Second Congo War,[d] also known as Africa's World War[82] or the Great War of Africa, was a major conflict that began on 2 August 1998 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), just over a year after the First Congo War. The war initially erupted when Congolese president Laurent-Désiré Kabila turned against his former allies from Rwanda and Uganda, who had helped him seize power. Eventually, the conflict expanded, drawing in nine African nations and approximately 25 armed groups, making it one of the largest wars in African history.[83]

Although a peace agreement was signed in 2002, and the war officially ended on 18 July 2003 with the establishment of the Transitional Government of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, violence has persisted in various regions, particularly in the east,[84] through ongoing conflicts such as the Lord's Resistance Army insurgency and the Kivu and Ituri conflicts.

The Second Congo War and its aftermath caused an estimated 5.4 million deaths, primarily due to disease and malnutrition,[85] making it the deadliest conflict since World War II, according to a 2008 report by the International Rescue Committee.[86] However, this figure has been disputed, with some researchers arguing that many of the deaths may have occurred regardless of the war and that the actual death toll was closer to 3 million.[87] The conflict also displaced approximately 2 million people, forcing them to flee their homes or seek asylum in neighboring countries.[84] Additionally, the war was heavily funded by the trade of conflict minerals, which continues to fuel violence in the region.[88][89]

Congo

Laurent-Désiré Kabila (French pronunciation: [lo.ʁɑ̃ de.zi.ʁe ka.bi.la]; 27 November 1939 – 16 January 2001)[90][91] usually known as Laurent Kabila (US: ⓘ), was a Congolese rebel and politician who served as the third president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1997 until his assassination in 2001.[92]

Kabila became known during the 1960s Congo Crisis as an opponent of Mobutu Sese Seko. He took part in the Simba rebellion and led the Communist-aligned Fizi rebel territory until the 1980s. In the 1990s, Kabila re-emerged as leader of the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo (ADFLC), a Rwandan and Ugandan-sponsored rebel group that invaded Zaire and overthrew Mobutu during the First Congo War from 1996 to 1997. Having now become the new president of the country, whose name was changed back to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kabila found himself in a delicate position as a puppet of his foreign backers.

The following year, he ordered the departure of all foreign troops from the country following the Kasika massacre to prevent a potential coup, leading to the Second Congo War, in which his former Rwandan and Ugandan allies began sponsoring several rebel groups to overthrow him. During the war, he was assassinated in 2001 by one of his bodyguards, and was succeeded ten days later by his 29-year-old son Joseph.[93]

Rwanda

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The Rwandan genocide, also known as the genocide against the Tutsi, occurred from 7 April to 19 July 1994 during the Rwandan Civil War.[94] Over a span of around 100 days, members of the Tutsi ethnic group, as well as some moderate Hutu and Twa, were systematically killed by Hutu militias. While the Rwandan Constitution states that over 1 million people were killed, most scholarly estimates suggest between 500,000 and 662,000 Tutsi died.[95][96] The genocide was marked by extreme violence, with victims often murdered by neighbors, and widespread sexual violence, with between 250,000 and 500,000 women raped.[97][98]

The genocide was rooted in long-standing ethnic tensions, exacerbated by the Rwandan Civil War, which began in 1990 when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a predominantly Tutsi rebel group, invaded Rwanda from Uganda. The war reached a tentative peace with the Arusha Accords in 1993. However, the assassination of President Juvénal Habyarimana on 6 April 1994 ignited the genocide, as Hutu extremists used the power vacuum to target Tutsi and moderate Hutu leaders.[99]

Despite the scale of the atrocities, the international community failed to intervene to stop the killings.[100] The RPF resumed military operations in response to the genocide, eventually defeating the government forces and ending the genocide by capturing all government-controlled territory. This led to the flight of the génocidaires and many Hutu refugees into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), contributing to regional instability and triggering the First Congo War in 1996.

The legacy of the genocide remains significant in Rwanda. The country has instituted public holidays to commemorate the event and passed laws criminalizing "genocide ideology" and "divisionism."[101][102]Asia

China

Jiang Zemin[e] (17 August 1926 – 30 November 2022) was a Chinese politician who served as general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from 1989 to 2002, as chairman of the Central Military Commission from 1989 to 2004, and as president of China from 1993 to 2003. Jiang was the third paramount leader of China from 1989 to 2002. He was the core leader of the third generation of Chinese leadership, one of four core leaders alongside Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Xi Jinping.

Born in Yangzhou, Jiangsu, Jiang joined the CCP while he was in college. After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, he received training at the Stalin Automobile Works in Moscow in the 1950s, later returning to Shanghai in 1962 to serve in various institutes, later being sent between 1970 and 1972 to Romania as part of an expert team to establish machinery manufacturing plants in the country. After 1979, he was appointed as the vice chair of two commissions by vice premier Gu Mu to oversee the newly established special economic zones (SEZs). He became the vice minister of the newly established Ministry of Electronics Industry and a member of the CCP Central Committee in 1982.

Jiang was appointed as the mayor of Shanghai in 1985, later being promoted to its Communist Party secretary, as well as a member of the CCP Politburo, in 1987. Jiang came to power unexpectedly as a compromise candidate following the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, when he replaced Zhao Ziyang as CCP general secretary after Zhao was ousted for his support for the student movement. As the involvement of the "Eight Elders" in Chinese politics steadily declined,[103] Jiang consolidated his hold on power to become the "paramount leader" in the country during the 1990s.[f] Urged by Deng Xiaoping's southern tour in 1992, Jiang officially introduced the term "socialist market economy" in his speech during the 14th CCP National Congress held later that year, which accelerated "opening up and reform".

Under Jiang's leadership, China experienced substantial economic growth with the continuation of market reforms. The returning of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom in 1997 and of Macau from Portugal in 1999, and entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001, were landmark moments of his era. China also witnessed improved relations with the outside world, while the Communist Party maintained its tight control over the state. Jiang faced criticism over human rights abuses, including the crackdown on the Falun Gong movement. His contributions to party doctrine, known as the "Three Represents", were written into the CCP constitution in 2002. Jiang gradually vacated his official leadership titles from 2002 to 2005, being succeeded in these roles by Hu Jintao, although he and his political faction continued to influence affairs until much later. In 2022, Jiang died at the age of 96 in Shanghai; he was accorded a state funeral.Europe

France

Jacques René Chirac (UK: /ˈʃɪəræk/,[104][105] US: /ʒɑːk ʃɪəˈrɑːk/ ⓘ;[105][106][107] French: [ʒak ʁəne ʃiʁak] ⓘ; 29 November 1932 – 26 September 2019) was a French politician who served as President of France from 1995 to 2007. He was previously Prime Minister of France from 1974 to 1976 and 1986 to 1988, as well as Mayor of Paris from 1977 to 1995.

After attending the École nationale d'administration, Chirac began his career as a high-level civil servant, entering politics shortly thereafter. Chirac occupied various senior positions, including minister of agriculture and minister of the interior. In 1981 and 1988, he unsuccessfully ran for president as the standard-bearer for the conservative Gaullist party Rally for the Republic (RPR). Chirac's internal policies initially included lower tax rates, the removal of price controls, strong punishment for crime and terrorism, and business privatisation.[108]

After pursuing these policies in his second term as prime minister, Chirac changed his views. He argued for different economic policies and was elected president in 1995, with 52.6% of the vote in the second round, beating Socialist Lionel Jospin, after campaigning on a platform of healing the "social rift" (fracture sociale).[109] Chirac's economic policies, based on dirigisme, allowing for state-directed investment, stood in opposition to the laissez-faire policies of the United Kingdom under the ministries of Margaret Thatcher and John Major, which Chirac described as "Anglo-Saxon ultraliberalism".[110]

Chirac was known for his stand against the American-led invasion of Iraq, his recognition of the collaborationist French government's role in deporting Jews, and his reduction of the presidential term from seven years to five through a referendum in 2000. At the 2002 presidential election, he won 82.2% of the vote in the second round against the far-right candidate, Jean-Marie Le Pen, and was the last president to be re-elected until 2022. In 2011, the Paris court declared Chirac guilty of diverting public funds and abusing public confidence, giving him a two-year suspended prison sentence.[111]

Germany

German reunification (German: Deutsche Wiedervereinigung) was the process of re-establishing Germany as a single sovereign state, which began on 9 November 1989 and culminated on 3 October 1990 with the dissolution of the German Democratic Republic and the integration of its re-established constituent federated states into the Federal Republic of Germany to form present-day Germany. This date was chosen as the customary German Unity Day, and has thereafter been celebrated each year as a national holiday in Germany since 1991.[112] On the same date, East and West Berlin were also reunified into a single city, which eventually became the capital of Germany.

The East German government, controlled by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED), started to falter on 2 May 1989, when the removal of Hungary's border fence with Austria opened a hole in the Iron Curtain. The border was still closely guarded, but the Pan-European Picnic and the indecisive reaction of the rulers of the Eastern Bloc set in motion an irreversible movement.[113][114] It allowed an exodus of thousands of East Germans fleeing to West Germany via Hungary. The Peaceful Revolution, part of the international revolutions of 1989 including a series of protests by East German citizens, led to the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989 and the GDR's first free elections later on 18 March 1990 and then to negotiations between the two countries that culminated in a Unification Treaty.[112] Other negotiations between the two Germanies and the four occupying powers in Germany produced the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, which granted on 15 March 1991 full sovereignty to a reunified German state, whose two parts were previously bound by a number of limitations stemming from their post-World War II status as occupation zones, though only on 31 August 1994 did the last Russian occupation troops leave Germany.

After the end of World War II in Europe, the old German Reich was abolished and Germany was occupied and divided by the four Allied countries. There was no peace treaty. Two countries emerged. The American-occupied, British-occupied, and French-occupied zones combined to form the FRG, i.e., West Germany, on 23 May 1949. The Soviet-occupied zone formed the GDR, i.e., East Germany, in October 1949. The West German state joined NATO in 1955. In 1990, a range of opinions continued to be maintained over whether a reunited Germany could be said to represent "Germany as a whole"[h] for this purpose. In the context of the revolutions of 1989; on 12 September 1990, under the Two Plus Four Treaty with the four Allies, both East and West Germany committed to the principle that their joint pre-1990 boundary constituted the entire territory that could be claimed by a government of Germany.

The reunited state is not a successor state, but an enlarged continuation of the 1949–1990 West German state. The enlarged Federal Republic of Germany retained the West German seats in the governing bodies of the European Economic Community (EEC) (later the European Union) and in international organizations including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the United Nations (UN), while relinquishing membership in the Warsaw Pact (WP) and other international organizations to which only East Germany belonged.Russia

Boris Nikolayevich Yeltsin[i] (1 February 1931 – 23 April 2007) was a Soviet and Russian politician and statesman who served as the president of Russia from 1991 to 1999. He was a member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1961 to 1990. He later stood as a political independent, during which time he was viewed as being ideologically aligned with liberalism.

Yeltsin was born in Butka, Ural Oblast. He would grow up in Kazan and Berezniki. He worked in construction after studying at the Ural State Technical University. After joining the Communist Party, he rose through its ranks, and in 1976, he became First Secretary of the party's Sverdlovsk Oblast committee. Yeltsin was initially a supporter of the perestroika reforms of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev. He later criticized the reforms as being too moderate and called for a transition to a multi-party representative democracy. In 1987, he was the first person to resign from the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which established his popularity as an anti-establishment figure. In 1990, he was elected chair of the Russian Supreme Soviet and in 1991 was elected president of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), becoming the first popularly-elected head of state in Russian history. Yeltsin allied with various non-Russian nationalist leaders and was instrumental in the formal dissolution of the Soviet Union in December of that year. With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the RSFSR became the Russian Federation, an independent state. Through that transition, Yeltsin remained in office as president. He was later reelected in the 1996 election, which critics claimed to be pervasively corrupt.

He oversaw the transition of Russia's command economy into a capitalist market economy by implementing economic shock therapy, market exchange rate of the ruble, nationwide privatization, and lifting of price controls. Economic downturn, volatility, and inflation ensued. Amid the economic shift, a small number of oligarchs obtained most of the national property and wealth, while international monopolies dominated the market. A constitutional crisis emerged in 1993 after Yeltsin ordered the unconstitutional dissolution of the Russian parliament, leading parliament to impeach him. The crisis ended after troops loyal to Yeltsin stormed the parliament building and stopped an armed uprising; he then introduced a new constitution which significantly expanded the powers of the president. After the crisis, Yeltsin governed the country in a rule by decree until 1994, as the Supreme Soviet of Russia was absent. Secessionist sentiment in the Russian Caucasus led to the First Chechen War, War of Dagestan, and Second Chechen War between 1994 and 1999. Internationally, Yeltsin promoted renewed collaboration with Europe and signed arms control agreements with the United States. Amid growing internal pressure, he resigned by the end of 1999 and was succeeded as president by his chosen successor, Vladimir Putin, whom he had appointed prime minister a few months earlier. After leaving office, he kept a low profile and was accorded a state funeral upon his death in 2007.

Domestically, he was highly popular in the late 1980s and early 1990s, although his reputation was damaged by the economic and political crises of his presidency, and he left office widely unpopular with the Russian population. He received praise and criticism for his role in dismantling the Soviet Union, transforming Russia into a representative democracy, and introducing new political, economic, and cultural freedoms to the country. Conversely, he was accused of economic mismanagement, abuse of presidential power, autocratic behavior, corruption, and of undermining Russia's standing as a major world power.

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration № 142-Н of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union.[115] It also brought an end to the Soviet Union's federal government and General Secretary (also President) Mikhail Gorbachev's effort to reform the Soviet political and economic system in an attempt to stop a period of political stalemate and economic backslide. The Soviet Union had experienced internal stagnation and ethnic separatism. Although highly centralized until its final years, the country was made up of 15 top-level republics that served as the homelands for different ethnicities. By late 1991, amid a catastrophic political crisis, with several republics already departing the Union and Gorbachev continuing the waning of centralized power, the leaders of three of its founding members, the Russian, Belorussian, and Ukrainian SSRs, declared that the Soviet Union no longer existed. Eight more republics joined their declaration shortly thereafter. Gorbachev resigned on 25 December 1991 and what was left of the Soviet parliament voted to dissolve the union.

The process began with growing unrest in the country's various constituent national republics developing into an incessant political and legislative conflict between them and the central government. Estonia was the first Soviet republic to declare state sovereignty inside the Union on 16 November 1988. Lithuania was the first republic to declare full independence restored from the Soviet Union by the Act of 11 March 1990 with its Baltic neighbors and the Southern Caucasus republic of Georgia joining it over the next two months.

During the failed 1991 August coup, communist hardliners and military elites attempted to overthrow Gorbachev and stop the failing reforms. However, the turmoil led to the central government in Moscow losing influence, ultimately resulting in many republics proclaiming independence in the following days and months. The secession of the Baltic states was recognized in September 1991. The Belovezha Accords were signed on 8 December by President Boris Yeltsin of Russia, President Kravchuk of Ukraine, and Chairman Shushkevich of Belarus, recognizing each other's independence and creating the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) to replace the Soviet Union.[116] Kazakhstan was the last republic to leave the Union, proclaiming independence on 16 December. All the ex-Soviet republics, with the exception of Georgia and the Baltic states, joined the CIS on 21 December, signing the Alma-Ata Protocol. Russia, as by far the largest and most populous republic, became the USSR's de facto successor state. On 25 December, Gorbachev resigned and turned over his presidential powers—including control of the nuclear launch codes—to Yeltsin, who was now the first president of the Russian Federation. That evening, the Soviet flag was lowered from the Kremlin for the last time and replaced with the Russian tricolor flag. The following day, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union's upper chamber, the Soviet of the Republics, formally dissolved the Union.[115] The events of the dissolution resulted in its 15 constituent republics gaining full independence which also marked the major conclusion of the Revolutions of 1989 and the end of the Cold War.[117]

In the aftermath of the Cold War, several of the former Soviet republics have retained close links with Russia and formed multilateral organizations such as the CIS, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), and the Union State, for economic and military cooperation. On the other hand, the Baltic states and all of the other former Warsaw Pact states became part of the European Union (EU) and joined NATO, while some of the other former Soviet republics like Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova have been publicly expressing interest in following the same path since the 1990s, despite Russian attempts to persuade them otherwise.United Kingdom

John Major's tenure as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom began on 28 November 1990 when he accepted an invitation from Queen Elizabeth II to form a government, succeeding Margaret Thatcher, and ended on 2 May 1997 upon his resignation. As prime minister, Major also served simultaneously as First Lord of the Treasury, Minister for the Civil Service, and Leader of the Conservative Party. Major's mild-mannered style and moderate political stance contrasted with that of Thatcher.

After Thatcher resigned as prime minister following a challenge to her leadership, Major entered the second stage of the contest to replace her and emerged victorious, becoming prime minister. Major went on to lead the Conservative Party to a fourth consecutive electoral victory at the 1992 election, the only election he won during his seven-year-premiership. Although the Conservatives lost 40 seats, they won over 14 million votes, which remains to this day a record for any British political party.

As prime minister, Major created the Citizen's Charter, removed the Poll Tax and replaced it with the Council Tax, committed British troops to the Gulf War, took charge of the UK's negotiations over the Maastricht Treaty of the European Union (EU),[118] led the country during the early 1990s economic crisis, withdrew the pound from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (a day which came to be known as Black Wednesday), promoted the socially conservative back to basics campaign, passed further reforms to education and criminal justice, privatised the railways and coal industry, and also played a pivotal role in creating peace in Northern Ireland.[119]

Internal Conservative Party divisions on the EU, a number of scandals involving Conservative MPs (widely known as "sleaze"), and questions about his economic credibility are seen as the main factors that led Major to resign as party leader in June 1995. However, he sought reelection as Conservative leader in the 1995 Conservative leadership election, and was comfortably re-elected. Notwithstanding, public opinion of his leadership was poor, both before and after. By December 1996, the government had lost its majority in the House of Commons due to a series of by-election defeats and an MP crossing the floor.[120] Major sought to rebuild public trust in the Conservatives following a series of scandals, including the events of Black Wednesday in 1992,[121][122] through campaigning on the strength of the economic recovery following the early 1990s recession, but faced divisions within the party over the UK's membership of the European Union.[122]

The Conservatives lost the 1997 general election in a landslide to the opposition Labour Party led by Tony Blair, ending 18 years of Conservative government. After Blair succeeded Major as prime minister, Major served as Leader of the Opposition for seven weeks while the leadership election to replace him took place. He formed a temporary shadow cabinet, and Major himself served as shadow foreign secretary and shadow secretary of state for defence. His resignation as Conservative leader formally took effect in June 1997 following the election of William Hague.North America

Guatemala

The Guatemalan Civil War ended in 1996 with a peace accord between the guerrillas and the government, negotiated by the United Nations through intense brokerage by nations such as Norway and Spain. Both sides made major concessions. The guerrilla fighters disarmed and received land to work. According to the U.N.-sponsored truth commission (the Commission for Historical Clarification), government forces and state-sponsored, CIA-trained paramilitaries were responsible for over 93% of the human rights violations during the war.[123]

In the last few years, millions of documents related to crimes committed during the civil war have been found abandoned by the former Guatemalan police. The families of over 45,000 Guatemalan activists who disappeared during the civil war are now reviewing the documents, which have been digitized. This could lead to further legal actions.[124]

During the first ten years of the civil war, the victims of the state-sponsored terror were primarily students, workers, professionals, and opposition figures, but in the last years they were thousands of mostly rural Maya farmers and non-combatants. More than 450 Maya villages were destroyed and over 1 million people became refugees or displaced within Guatemala.

In 1995, the Catholic Archdiocese of Guatemala began the Recovery of Historical Memory (REMHI) project,[125] known in Spanish as "El Proyecto de la Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica", to collect the facts and history of Guatemala's long civil war and confront the truth of those years. On 24 April 1998, REMHI presented the results of its work in the report "Guatemala: Nunca Más!". This report summarized testimony and statements of thousands of witnesses and victims of repression during the Civil War. "The report laid the blame for 80 per cent of the atrocities at the door of the Guatemalan Army and its collaborators within the social and political elite."[126]

Catholic Bishop Juan José Gerardi Conedera worked on the Recovery of Historical Memory Project and two days after he announced the release of its report on victims of the Guatemalan Civil War, "Guatemala: Nunca Más!", in April 1998, Bishop Gerardi was attacked in his garage and beaten to death.[126] In 2001, in the first trial in a civilian court of members of the military in Guatemalan history, three Army officers were convicted of his death and sentenced to 30 years in prison. A priest was convicted as an accomplice and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.[127]

According to the report, Recuperación de la Memoria Histórica (REMHI), some 200,000 people died. More than one million people were forced to flee their homes and hundreds of villages were destroyed. The Historical Clarification Commission attributed more than 93% of all documented violations of human rights to Guatemala's military government, and estimated that Maya Indians accounted for 83% of the victims. It concluded in 1999 that state actions constituted genocide.[128][129]

In some areas such as Baja Verapaz, the Truth Commission found that the Guatemalan state engaged in an intentional policy of genocide against particular ethnic groups in the Civil War.[123] In 1999, US President Bill Clinton said that the US had been wrong to have provided support to the Guatemalan military forces that took part in these brutal civilian killings.[130]

United States

As a result of conflicts between Democratic President Bill Clinton and the Republican Congress over funding for education, the environment, and public health in the 1996 federal budget, the United States federal government shut down from November 14 through November 19, 1995, and from December 16, 1995, to January 6, 1996, for 5 and 21 days, respectively. Republicans also threatened not to raise the debt ceiling.

The first shutdown occurred after Clinton vetoed the spending bill the Republican-controlled Congress sent him, as Clinton opposed the budget cuts favored by Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich and other Republicans. The first budget shutdown ended after Congress passed a temporary budget bill, but the government shut down again after Republicans and Democrats were unable to agree on a long-term budget bill. The second shutdown ended with congressional Republicans accepting Clinton's budget proposal. The first of the two shutdowns caused the furlough of about 800,000 workers, while the second caused about 284,000 workers to be furloughed.[131]

Polling generally showed that most respondents blamed congressional Republicans for the shutdowns, and Clinton's handling of the shutdowns may have bolstered his ultimately successful campaign in the 1996 presidential election. The second of the two shutdowns was the longest government shutdown in U.S. history until the 2018–2019 government shutdown surpassed it in January 2019.

Bill Clinton's tenure as the 42nd president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 1993, and ended on January 20, 2001. Clinton, a Democrat from Arkansas, took office following his victory over Republican incumbent president George H. W. Bush and independent businessman Ross Perot in the 1992 presidential election. Four years later, in the 1996 presidential election, he defeated Republican nominee Bob Dole and Perot again (then as the nominee of the Reform Party), to win re-election. Clinton served two terms and was succeeded by Republican George W. Bush, who won the 2000 presidential election.

Clinton's presidency coincided with the rise of the Internet. This rapid rise of the Internet under Clinton led to several dot-com startups, which quickly became popular investments and business ventures. The dot-com bubble from 1997 to 2000 as a result of these startups saw massive stock gains in the Nasdaq Composite and the S&P 500, although these gains would eventually be lost in their entirety by 2003. Clinton oversaw the longest period of peacetime economic expansion in American history. Months into his first term, he signed the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993, which raised taxes and set the stage for future budget surpluses. He signed the bipartisan Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act and won ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement, despite opposition from trade unions and environmentalists. Clinton's most ambitious legislative initiative, a plan to provide universal health care, faltered, as it never had majority support in Congress due to the Republican Revolution. In the 1994 elections, the Republican Revolution swept the country. Clinton vetoed the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act of 1995. He assembled a bipartisan coalition to pass welfare reform and successfully expanded health insurance for children.

While Clinton's economy was strong, his presidency oscillated dramatically from high to low and back again, which historian Gil Troy characterized in six Acts. Act I in early 1993 was "Bush League" with amateurish distractions. By mid-1993 Clinton had recovered to Act II, passing a balanced budget and the NAFTA trade deal. Act III, 1994, saw the Republicans mobilizing under Newt Gingrich, defeating Clinton's healthcare reforms, and taking control of the House of Representatives for the first time in forty years. The years 1995 to 1997 saw the comeback in Act IV, with a triumphant reelection landslide in 1996. However, Act V, the Monica Lewinsky scandal and impeachment made 1998 a lost year. Clinton concluded happily with Act VI by deregulating the banking system in 1999.[132] In foreign policy, Clinton initiated a bombing campaign in the Balkans, which led to the creation of a United Nations protectorate in Kosovo. He played a major role of the expansion of NATO into former Eastern Bloc countries and remained on positive terms with Russian President Boris Yeltsin. During his second term, Clinton presided over the deregulation of the financial and telecommunications industry. Clinton's second term also saw the first federal budget surpluses since the 1960s. The ratio of debt held by the public to GDP fell from 47.8% in 1993 to 33.6% by 2000. His impeachment in 1998 arose after he denied claims of having an affair with a White House intern, Monica Lewinsky under oath. He was acquitted of all charges by the Senate. He appointed Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer to the U.S. Supreme Court.

With a 66% approval rating at the time he left office, Clinton had the highest exit approval rating of any president since the end of World War II.[133] His preferred successor, Vice President Al Gore, was narrowly defeated by George W. Bush in the heavily-contested 2000 presidential election, winning the popular vote. Historians and political scientists generally rank Clinton as an above-average president.South America

Brazil

The Collor government, also referred to as the Collor Era, was a period in Brazilian political history that began with the inauguration of President Fernando Collor de Mello on 15 March 1990, and ended with his resignation from the presidency on 29 December 1992. Fernando Collor was the first president elected by the people since 1960, when Jânio Quadros won the last direct election for president before the beginning of the Military Dictatorship.[134] His removal from office on 2 October 1992, was a consequence of his impeachment proceedings the day before,[135][136] followed by cassation.[137]

At the time, the national media also referred to the government by República das Alagoas (English: Republic of Alagoas). "It was synonymous for trouble. Journalists love labels, and that one seemed perfect", Ricardo Motta recalls.[138]

The Collor administration registered a 2.06% retraction in GDP and a 6.97% retraction in per capita income.[139]

Among the main laws sanctioned, the following can be cited: Consumer Defense Code (1990), Statute of the Child and Adolescent (1990), Law of the Legal Regime of Public Service Employees (1990), SUS Law (1990), Rouanet Law (1991), Law of Administrative Improbity (1992).[140][141]The first post-military-regime president elected by popular suffrage, Fernando Collor de Mello (1990–92), was sworn into office in March 1990.[142] Facing imminent hyperinflation and a virtually bankrupt public sector, the new administration introduced a stabilization plan, together with a set of reforms, aimed at removing restrictions on free enterprise, increasing competition, privatizing public enterprises, and boosting productivity.[142]

Heralded as a definitive blow to inflation, the stabilization plan was drastic.[142] It imposed an eighteen-month freeze on all but a small portion of the private sector's financial assets, froze prices, and again abolished indexation.[142] The new administration also introduced provisional taxes to deal with the fiscal crisis, and took steps to reform the public sector by closing several public agencies and dismissing public servants.[142] These measures were expected not only to swiftly reduce inflation but also to lower inflationary expectations.[142] Collor also implemented a radical liquidity freeze, reducing the money stock by 80% by freezing bank accounts in excess of $1000.[143]

Brazil adopted neoliberalism in the late 1980s, with support from the workers party on the left. Brazil ended the old policy of closed economies with development focused through import substitution industrialization, in favor of a more open economic system and privatization. For example, tariff rates were cut from 32 percent in 1990 to 14 percent in 1994. The market reforms and trade reforms resulted in price stability and faster inflow of capital, but did not change levels of income inequality and poverty.[144]

At first few of the new administration's programs succeeded.[142] Major difficulties with the stabilization and reform programs were caused in part by the superficial nature of many of the administration's actions and by its inability to secure political support.[142] Moreover, the stabilization plan failed because of management errors coupled with defensive actions by segments of society that would be most directly hurt by the plan.[142] Confidence in the government was also eroded as a result of the liquidity freeze combined with an alienated industrial sector who had not been consulted in the plan.[143]

After falling more than 80 percent in March 1990, the CPI's monthly rate of growth began increasing again.[142] The best that could be achieved was to stabilize the CPI at a high and slowly rising level.[142] In January 1991, it rose by 19.9%, reaching 32% a month by July 1993.[142] Simultaneously, political instability increased sharply, with negative impacts on the economy.[142] The real GDP declined 4.0% in 1990, increased only 1.1% in 1991, and again declined 0.9% in 1992.[142]

President Collor de Mello was impeached in September 1992 on charges of corruption.[142] Vice president Itamar Franco was sworn in as president (1992–94), but he had to grapple to form a stable cabinet and to gather political support.[142] The weakness of the interim administration prevented it from tackling inflation effectively.[142] In 1993 the economy grew again, but with inflation rates higher than 30 percent a month, the chances of a durable recovery appeared to be very slim.[142] At the end of the year, it was widely acknowledged that without serious fiscal reform, inflation would remain high and the economy would not sustain growth.[142] This acknowledgment and the pressure of rapidly accelerating inflation finally jolted the government into action.[142] The president appointed a determined minister of finance, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, and a high-level team was put in place to develop a new stabilization plan.[142] Implemented early in 1994, the plan met little public resistance because it was discussed widely and it avoided price freezes.[142]

The stabilization program, called Plano Real had three stages: the introduction of an equilibrium budget mandated by the National Congress a process of general indexation (prices, wages, taxes, contracts, and financial assets); and the introduction of a new currency, the Brazilian real (pegged to the dollar).[142] The legally enforced balanced budget would remove expectations regarding inflationary behavior by the public sector. By allowing a realignment of relative prices, general indexation would pave the way for monetary reform.[142] Once this realignment was achieved, the new currency would be introduced, accompanied by appropriate policies (especially the control of expenditures through high interest rates and the liberalization of trade to increase competition and thus prevent speculative behavior).[142]

By the end of the first quarter of 1994, the second stage of the stabilization plan was being implemented. Economists of different schools of thought considered the plan sound and technically consistent.[142]

The presidency of Itamar Franco began on 29 December 1992, with the resignation of Fernando Collor de Mello, and ended on 1 January 1995, when Fernando Henrique Cardoso took office.[145]

Itamar government was characterized by the stabilization of the economy and the control of inflation, which occurred after the nomination of Fernando Henrique Cardoso to the Ministry of Finance, whose main project was the Plano Real (English: Real Plan). His administration was informally known as the República do Pão de Queijo ("Republic of Cheese Bread"), as the majority of his cabinet was composed of people from Minas Gerais. He advocated the relaunch of the VW Beetle, which became known as the Fusca do Itamar ("Itamar VW Beetle"). It recorded 10% growth in GDP and 6.78% in per capita income. Itamar assumed office with inflation at 1191.09% and handed over at 22.41%.[146][147][145]

The presidency of Fernando Henrique Cardoso began on 1 January 1995, with the inauguration of Fernando Henrique, also known as FHC, and ended on 1 January 2003, when Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took over the presidency.[148]

The main achievements of his administration were the maintenance of economic stability with the consolidation of the Real Plan, the privatization of state-owned companies, the creation of regulatory agencies, the changes to the legislation governing civil servants and the introduction of income transfer programs such as Bolsa Escola.[148][149]

The FHC government recorded GDP growth of 19.39% (an average of 2.42%) and per capita income growth of 6.99% (an average of 0.87%). He took office with inflation at 22.41% and left at 12.53%.[148]Oceania

Australia

Paul John Keating (born 18 January 1944) is an Australian former politician who served as the 24th prime minister of Australia from 1991 to 1996, holding office as the leader of the Labor Party (ALP). He previously served as treasurer under Prime Minister Bob Hawke from 1983 to 1991 and as the seventh deputy prime minister from 1990 to 1991.

Keating was born in Sydney and left school at the age of 14. He joined the Labor Party at the same age, serving a term as State president of Young Labor and working as a research assistant for a trade union. He was elected to the Australian House of Representatives at the age of 25, winning the division of Blaxland at the 1969 election. Keating briefly was minister for Northern Australia from October to November 1975, in the final weeks of the Whitlam government - along with Doug McClelland, Keating is the last surviving minister who served under Gough Whitlam. After the Dismissal removed Labor from power, he held senior portfolios in the Shadow Cabinets of Whitlam and Bill Hayden. During this time he came to be seen as the leader of the Labor Right faction, and developed a reputation as a talented and fierce parliamentary performer.

After Labor's landslide victory at the 1983 election, Keating was appointed treasurer by prime minister Bob Hawke. The pair developed a powerful political partnership, overseeing significant reforms intended to liberalise and strengthen the Australian economy. These included the Prices and Incomes Accord, the float of the Australian dollar, the elimination of tariffs, the deregulation of the financial sector, achieving the first federal budget surplus in Australian history, and reform of the taxation system, including the introduction of capital gains tax, fringe benefits tax, and dividend imputation. He also became recognised for his sardonic rhetoric, as a controversial but deeply skilled orator.[150][151] Keating became deputy prime minister in 1990, but in June 1991 he resigned from the government to unsuccessfully challenge Hawke for the leadership, believing he had reneged on the Kirribilli Agreement. He mounted a second successful challenge six months later, and became prime minister.

Keating was appointed prime minister in the aftermath of the early 1990s economic downturn, which he had famously described as "the recession we had to have". This, combined with poor opinion polling, led many to predict Labor was certain to lose the 1993 election, but Keating's government was re-elected in an upset victory. In its second term, the Keating government enacted the landmark Native Title Act to enshrine Indigenous land rights, introduced compulsory superannuation and enterprise bargaining, created a national infrastructure development program, privatised Qantas, Commonwealth Serum Laboratories and the Commonwealth Bank, established the APEC leaders' meeting, and promoted republicanism by establishing the Republic Advisory Committee.

At the 1996 election, after 13 years in office, his government suffered a landslide defeat to the Liberal–National Coalition, led by John Howard. Keating resigned as leader of the Labor Party and retired from Parliament shortly after the election, with his deputy Kim Beazley being elected unopposed to replace him. Keating has since remained active as a political commentator, whilst maintaining a broad series of business interests, including serving on the international board of the China Development Bank from 2005 to 2018.

As prime minister, Keating performed poorly in opinion polls, and in August 1993, received the lowest approval rating for any Australian prime minister since modern political polling began.[152] Since leaving office, Keating received broad praise from historians and commentators for his role in modernising the Australian economy as treasurer, although ratings of his premiership have been mixed.[153][154][155][156] Keating has been recognised across the political spectrum for his charisma, debating skills, and his willingness to boldly confront social norms,[150] including his famous Redfern Park Speech on the impact of colonisation in Australia and Aboriginal reconciliation.[157]

John Winston Howard (born 26 July 1939) is an Australian former politician who served as the 25th prime minister of Australia from 1996 to 2007. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia, his eleven-year tenure as prime minister is the second-longest in Australian history, behind only Sir Robert Menzies. Howard has also been the oldest living Australian former prime minister since the death of Bob Hawke in May 2019.

Howard was born in Sydney and studied law at the University of Sydney. He was a commercial lawyer before entering parliament. A former federal president of the Young Liberals, he first stood for office at the 1968 New South Wales state election, but lost narrowly. At the 1974 federal election, Howard was elected as a member of parliament (MP) for the division of Bennelong. He was promoted to cabinet in 1977, and later in the year replaced Phillip Lynch as treasurer of Australia, remaining in that position until the defeat of Malcolm Fraser's government at the 1983 election. In 1985, Howard was elected leader of the Liberal Party for the first time, thus replacing Andrew Peacock as Leader of the Opposition. He led the Liberal–National coalition to the 1987 federal election, but lost to Bob Hawke's Labor government, and was removed from the leadership in 1989. Remaining a key figure in the party, Howard was re-elected leader in 1995, replacing Alexander Downer, and subsequently led the Coalition to a landslide victory at the 1996 federal election.

In his first term, Howard introduced reformed gun laws in response to the Port Arthur massacre, and controversially implemented a nationwide value-added tax, breaking a pre-election promise. The Howard government called a snap election for October 1998, which they won, albeit with a greatly reduced majority. Going into the 2001 election, the Coalition trailed behind Labor in opinion polling. However, in a campaign dominated by national security, Howard introduced changes to Australia's immigration system to deter asylum seekers from entering the country, and pledged military assistance to the United States following the September 11 attacks. Due to this, Howard won widespread support, and his government would be narrowly re-elected.

In Howard's third term in office, Australia contributed troops to the War in Afghanistan and the Iraq War, and led the International Force for East Timor. The Coalition would be re-elected once more at the 2004 federal election. In his final term in office, his government introduced industrial relations reforms known as WorkChoices, which proved controversial and unpopular with the public. The Howard government was defeated at the 2007 federal election, with the Labor Party's Kevin Rudd succeeding him as prime minister. Howard also lost his own seat of Bennelong at the election to Maxine McKew, becoming only the second prime minister to do so, after Stanley Bruce at the 1929 election. Following this loss, Howard retired from politics, but has remained active in political discourse.

Howard's government presided over a sustained period of economic growth and a large "mining boom", and significantly reduced government debt by the time he left office. He was known for his broad appeal to voters across the political spectrum, and commanded a diverse base of supporters, colloquially referred to as his "battlers".[158][159] Retrospectively, ratings of Howard's premiership have been polarised. His critics have admonished him for involving Australia in the Iraq War, his policies regarding asylum seekers, and his economic agenda.[160][161][162] Nonetheless, he has been frequently ranked within the upper-tier of Australian prime ministers by political experts and the general public.[163][164][165]Notes

- ^ Including 100–120,000 military deaths, 3–15,000 civilian deaths during the war, 4–6,000 civilian deaths up to April 1991, and 35–65,000 civilian deaths from the Iraqi uprisings after the end of the Gulf War.

- ^ At least when running only 32-bit protected mode applications

- ^ French: Première guerre du Congo

- ^ French: Deuxième guerre du Congo

- ^ /dʒiːˈɑːŋ zəˈmɪn/; Chinese: 江泽民; pinyin: Jiāng Zémín, traditionally romanized as Chiang Tze-min

- ^ "Paramount leader" is not a formal title; it is a reference occasionally used by media outlets and scholars to refer to the foremost political leader in China at a given time. For example, there is no consensus on when Hu Jintao became the paramount leader (2002–2012), as Jiang held the most powerful office in the military (i.e., Central Military Commission chairman) and did not relinquish all positions until 2005 to his successor, while Hu was the General Secretary of the Communist Party since 2002 and President of China since 2003.

- ^ The Saarland was de facto separated from occupied Germany to become a protectorate in 1947, it became part of West Germany in 1957.

- ^ The sentence "Germany as a whole" was recorded in the Potsdam Agreement to mention Germany.

- ^ Russian: Борис Николаевич Ельцин, IPA: [bɐˈrʲis nʲɪkɐˈlajɪvʲɪtɕ ˈjelʲtsɨn] ⓘ.

- ^ Some historians only narrow the conflicts to Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo in the 1990s.[4] Others also include the Preševo Valley insurgency and 2001 Macedonian insurgency.

References

- ^ Judah, Tim (17 February 2011). "Yugoslavia: 1918–2003". BBC. Archived from the original on 31 May 2019. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ Finlan (2004), p. 8.

- ^ Naimark (2003), p. xvii.

- ^ Shaw (2013), p. 132.

- ^ Armatta, Judith (2010), Twilight of Impunity: The War Crimes Trial of Slobodan Milosević, Duke University Press, p. 121

- ^ Annex IV – II. The politics of creating a Greater Serbia: nationalism, fear and repression

- ^ Janssens, Jelle (2015). State-building in Kosovo. A plural policing perspective. Maklu. p. 53. ISBN 978-90-466-0749-7. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Totten, Samuel; Bartrop, Paul R. (2008). Dictionary of Genocide. with contributions by Steven Leonard Jacobs. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-313-32967-8. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Sullivan, Colleen (14 September 2014). "Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Karon, Tony (9 March 2001). "Albanian Insurgents Keep NATO Forces Busy". TIME. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Phillips, David L. (2012). Liberating Kosovo: Coercive Diplomacy and U.S. Intervention. in cooperation with the Future of Diplomacy Project, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. The MIT Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-262-30512-9. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (29 May 2013). "Prlic et al. judgement vol. 6 2013" (PDF). United Nations. p. 383. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Gow, James (2003). The Serbian Project and Its Adversaries: A Strategy of War Crimes. C. Hurst & Co. p. 229. ISBN 978-1-85065-499-5. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ van Meurs, Wim, ed. (2013). Prospects and Risks Beyond EU Enlargement: Southeastern Europe: Weak States and Strong International Support. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 168. ISBN 978-3-663-11183-2. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Thomas, Raju G. C., ed. (2003). Yugoslavia Unraveled: Sovereignty, Self-Determination, Intervention. Lexington Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7391-0757-7. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Mahmutćehajić, Rusmir (2012). Sarajevo Essays: Politics, Ideology, and Tradition. State University of New York Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-7914-8730-3. Archived from the original on 8 February 2023. Retrieved 8 February 2023.

- ^ Bosnia Genocide, United Human Rights Council, archived from the original on 22 April 2009, retrieved 13 April 2015

- ^ United Nations Security Council Resolution 827. S/RES/827(1993) 25 May 1993.

- ^ "Transitional Justice in the Former Yugoslavia". International Center for Transitional Justice. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- ^ "About us". Humanitarian Law Center. Archived from the original on 22 May 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- ^ "The Balkan Refugee Crisis". Crisis Group. June 1999. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ "Crisis in the Balkans". Chomsky.info. Archived from the original on 29 September 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ "Bosnia and Herzegovina: The Fall of Srebrenica and the Failure of UN Peacekeeping". Human Rights Watch. 1995-10-15. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ "MEI - The agreement on free trade in the Balkans (cefta)". www.mei.gov.rs. Retrieved 2024-10-14.

- ^ "Desert Shield And Desert Storm: A Chronology And Troop List for the 1990–1991 Persian Gulf Crisis" (PDF). apps.dtic.mil. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 2018-12-18.

- ^ {{cite web|url=https://history.state.gov/departmenthistory/short-history/firstgulf%7Ctitle=The First Gulf War|publisher=US Government

- ^ Persian Gulf War, the Sandhurst-trained Prince

Khaled bin Sultan al-Saud was co-commander with General Norman Schwarzkopf www.casi.org.uk/discuss Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine - ^ General Khaled was Co-Commander, with US General Norman Schwarzkopf, of the allied coalition that liberated Kuwait www.thefreelibrary.com Archived 30 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Knights, Michael (2005). Cradle of Conflict: Iraq and the Birth of Modern U.S. Military Power. United States Naval Institute. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-59114-444-1.

- ^ a b "Persian Gulf War". MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009.

- ^ 18 M1 Abrams, 11 M60, 2 AMX-30

- ^ CheckPoint, Ludovic Monnerat. "Guerre du Golfe: le dernier combat de la division Tawakalna".

- ^ Scales, Brig. Gen. Robert H.: Certain Victory. Brassey's, 1994, p. 279.

- ^ Halberstadt 1991. p. 35

- ^ Atkinson, Rick. Crusade, The untold story of the Persian Gulf War. Houghton Mifflin Company, 1993. pp. 332–3

- ^ Captain Todd A. Buchs, B. Co. Commander, Knights in the Desert. Publisher/Editor Unknown. p. 111.

- ^ Malory, Marcia. "Tanks During the First Gulf War – Tank History". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ M60 vs T-62 Cold War Combatants 1956–92 by Lon Nordeen & David Isby

- ^ "TAB H – Friendly-fire Incidents". Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ^ NSIAD-92-94, "Operation Desert Storm: Early Performance Assessment of Bradley and Abrams". Archived 21 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine US General Accounting Office, 10 January 1992. Quote: "According to information provided by the Army's Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations and Plans, 20 Bradleys were destroyed during the Gulf war. Another 12 Bradleys were damaged, but four of these were quickly repaired. Friendly fire accounted for 17 of the destroyed Bradleys and three of the damaged ones

- ^ Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait; 1990 (Air War) Archived 6 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Acig.org. Retrieved on 12 June 2011

- ^ a b c d e Bourque (2001), p. 455.

- ^ "Appendix – Iraqi Death Toll | The Gulf War | FRONTLINE | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2021-07-24.

- ^ Tucker-Jones, Anthony (31 May 2014). The Gulf War: Operation Desert Storm 1990–1991. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-3730-0. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Human Rights Watch". Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Appendix A: Chronology – February 1991". Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 2024-02-04.

- ^ "Iraq air force wants Iran to give back its planes". Reuters. 10 August 2007.

- ^ "The Use of Terror during Iraq's invasion of Kuwait". The Jewish Agency for Israel. Archived from the original on 24 January 2005. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- ^ "Kuwait: missing people: a step in the right direction". Red Cross. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ "The Wages of War: Iraqi Combatant and Noncombatant Fatalities in the 2003 Conflict". Project on Defense Alternatives. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ Collateral damage: The health and environmental costs of war on Iraq Archived 19 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Medact

- ^ Tobin, James (2012-06-12). Great Projects: The Epic Story of the Building of America, from the Taming of the Mississippi to the Invention of the Internet. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-1476-6.

- ^ In, Lee (2012-06-30). Electronic Commerce Management for Business Activities and Global Enterprises: Competitive Advantages: Competitive Advantages. IGI Global. ISBN 978-1-4666-1801-5.

- ^ Misiroglu, Gina (2015-03-26). American Countercultures: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in US History: An Encyclopedia of Nonconformists, Alternative Lifestyles, and Radical Ideas in US History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47729-7.

- ^ Couldry, Nick (2012). Media, Society, World: Social Theory and Digital Media Practice. London: Polity Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-7456-3920-8.

- ^ Viswanathan, Ganesh; Dutt Mathur, Punit; Yammiyavar, Pradeep (March 2010). From Web 1.0 to Web 2.0 and beyond: Reviewing usability heuristic criteria taking music sites as case studies. IndiaHCI Conference. Mumbai. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "Is There a Web 1.0?". HowStuffWorks. January 28, 2008.

- ^ "Web 1.0 Revisited – Too many stupid buttons". Complexify.com. Archived February 16, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Right Size of Software". www.catb.org.

- ^ Jurgenson, Nathan; Ritzer, George (2012-02-02), Ritzer, George (ed.), "The Internet, Web 2.0, and Beyond", The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Sociology, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 626–648, doi:10.1002/9781444347388.ch33, ISBN 978-1-4443-4738-8

- ^ "The greatest defunct Web sites and dotcom disasters". CNET. June 5, 2008. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved February 10, 2020.

- ^ a b Kumar, Rajesh (December 5, 2015). Valuation: Theories and Concepts. Elsevier. p. 25.

- ^ Powell, Jamie (2021-03-08). "Investors should not dismiss Cisco's dot com collapse as a historical anomaly". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 2022-04-06.

- ^ a b Segal, David (August 24, 1995). "With Windows 95's Debut, Microsoft Scales Heights of Hype". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2019.