1821 Norfolk and Long Island hurricane

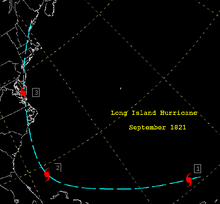

Estimated track of the 1821 Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane from NOAA. | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | Unknown |

| Dissipated | September 4, 1821 |

| Category 4 major hurricane | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/NWS) | |

| Highest winds | ≥130 mph (≥215 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | <965 mbar (hPa); <28.50 inHg (estimated) |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | ≥22 direct |

| Injuries | Unknown |

| Damage | $200,000 (1821 USD) |

| Areas affected | East Coast of the United States, (especially North Carolina and Delmarva Peninsula) |

| [1] | |

Part of the 1821 Atlantic hurricane season | |

The 1821 Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane was an intense and record breaking tropical cyclone that devastated the East Coast of the United States in early September & was one of four known tropical cyclones that have made landfall in New York City. It has been estimated that a similar hurricane would cause about $250 billion in damages if a similar storm were to occur in 2014.[2] Despite that, an even earlier and more intense hurricane struck the greater area during the pre-Columbian era (between 1278 and 1438) which left evidence that was detected in South Jersey via paleotempestological research.[3] A third and more recent storm was the 1893 New York hurricane, while the fourth was Hurricane Irene in 2011.

The storm was the first of three tropical cyclones recorded in the 1821 Atlantic hurricane season, and was first observed off the southeast United States coast on September 1 likely as a major hurricane. It then moved ashore near Wilmington, North Carolina during the late part of September 2. It then passed near Norfolk, Virginia before moving striking the Delmarva Peninsula and New Jersey on September 3. Shortly after, the hurricane struck modern day Jamaica Bay, which would later become part of New York City. The storm was last observed over New England on September 4, just 6 years after the destructive Great September Gale of 1815.

Meteorological history

A tropical cyclone was first observed on September 1 off the southeast coast of the United States. Initially, it was believed to be the same storm that struck Guadeloupe on the same day, though subsequent research indicated there were two separate storms.[4] The hurricane then tracked by the Bahamas, and had likely already attained major hurricane status while in the open Atlantic. It then began approaching the United States coastline with sustained winds estimated of at least 130 mph (210 km/h). Some estimates suggest the storm likely reached high-end Category 4 to Category 5 status on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale sometime before making landfall near Wilmington, North Carolina.[5] This would make it the most intense tropical cyclone to make landfall at such a latitude in the world. It later turned to the northeast to cross the Pamlico Sound.[6]

The hurricane then accelerated northeastward, and passed over the Hampton Roads area early on September 3. After crossing the Chesapeake Bay, the cyclone made its 2nd landfall around Assateague Island shortly before striking modern day Ocean City, Maryland likely as a high-end Category 3 or Category 4 storm.[6] It then continued to traversed the Delmarva Peninsula near the Atlantic coastline. At ~1500 UTC, the eye passed directly over Cape Henlopen, Delaware where a thirty-minute period of calm was reported. The storm then began its journey across the Delaware Bay until it made landfall and passed over Cape May, New Jersey where a fifteen-minute calm was also reported.[7] Modern researchers estimate it was still a Category 3 or 4 hurricane upon striking New Jersey, and one of few hurricanes to hit the state.[8][9]

The hurricane continued to parallel the coastline just inland until it exited into Lower New York Bay where the hurricane made its fourth and final landfall in New York City at ~1930 UTC, during a very low tide.[3] Some researchers suggest it was still a Category 3 at the time, which would make it the only major hurricane to directly hit the city.[10] The storm had an unusually fast forward speed of 35 mph (55 km/h) and pressure of 965 mbar upon moving ashore.[10][1] The storm then continued northeastward through New England, and began losing its identity upon entering Massachusetts on September 4.[11] One researcher suggest that the cyclone tracked northeastward over southeastern Maine,[6] while another assessed the storm as passing far west of Maine.[12]

Based on the arrangement of effects caused in New England from the storm, meteorologist William C. Redfield deduced that the wind field & center of tropical cyclones are circular in nature. Previous of this, they were believed to have been in a straight line.[12]

Impact

The continuous cataracts of rain swept impetuously along, darkening the expanse of vision and apparently confounding the heaven, earth and seas in a general chaos

In North Carolina, a powerful storm surge flooded large portions of Portsmouth Island; residents estimated the island would have been completely under water had the worst of the storm lasted for two more hours. Strong winds occurred across eastern North Carolina, resulting in at least 76 destroyed houses. Numerous people were killed in Currituck.[7]

The strongest winds of the hurricane lasted for about an hour in southeastern Virginia, after which the storm rapidly abated. Several houses were completely destroyed, with many others receiving moderate to severe damage. The winds destroyed most of the roof of the courthouse, and uprooted trees across the region; fallen tree limbs damaged a stone bridge in Norfolk. The hurricane produced a strong storm surge along the Virginia coastline, which reached at least 10 feet (3.0 m) at Pungoteague along the Delmarva Peninsula. The storm surge, which reached several hundred yards inland, destroyed two bridges and flooded many warehouses along the Elizabeth River. Rough waves grounded the USS Guerriere and the USS Congress, and also destroyed several schooners and brigs. Along the eastern shore, the storm surge flooded barrier islands along the Atlantic coastline, causing severe crop damage and downing many trees. Several houses were destroyed, and at Pungoteague the impact of the hurricane was described as "unexampled destruction". At least five people drowned in Chincoteague. The storm is considered to be one of the most violent hurricanes on record in the Mid-Atlantic, and caused $200,000 in damage in Virginia (1821 USD, or ~$5.6 million 2024 USD).[6]

Gale-force winds affected the Delmarva Peninsula and on Poplar Island in Talbot County, Maryland, where winds peaked ~1600 UTC on September 3.[7] The strongest winds were confined to the Atlantic coastline, however outer rainbands still produced heavy rainfall in greater Baltimore-Washington D.C. area.[13] Fierce winds were observed in Cape Henlopen, Delaware, with the strongest gales occurring after the eye passed over the area.[7]

Upon making landfall on Cape May, New Jersey, the cyclone produced a 5-foot (1.5 m) storm surge on the Delaware Bay side of the city.[13] Lasting for several hours, the hurricane-force winds were described as "blowing with great violence",[7] and caused widespread devastation across the region.[13] Wind gusts in Cape May County reached over 110 mph (180 km/h), and around 130 mph (210 km/h) in Atlantic County.[2] In Little Egg Harbor, the hurricane caused catastrophic damaged to the port. Strong winds reached as far inland as Philadelphia, where winds of over 40 mph (65 km/h) downed trees and chimneys. Precipitation in the city accrued to 3.92 inches (100 mm). Further to the north, the hurricane destroyed a windmill at Bergen Point, New Jersey.[13] Despite the hurricane occurring during low tide, it still produced a storm surge of over 29 feet (8.8 m) along several portions of the New Jersey coastline, causing significant overwash.[3]

The hurricane also produced an extraordinarily high storm surge of 13 feet (4.0 m) in merely an hour at Battery Park; a record only broken 191 years later by Hurricane Sandy. Manhattan Island was completely flooded to Canal Street. Even despite the record flooding, the storm surge would have been much greater if it had not struck at low tide.[14] Fortunately, only a few deaths were reported in the city due to the affected neighborhoods being much less populated than the modern day.[15] The hurricane also brought light rainfall and strong winds that left severe damage across the city. High tides occurred along the Hudson River. Strong waves and winds blew many ships ashore along Long Island in which sinking ship killed 17 people. Along Long Island, the winds destroyed several buildings and left crops destroyed.[13]

In New England, the hurricane produced widespread gale-force winds, with damage being greatest in Connecticut.[11] The Black Rock Harbor Light in Black Rock, Connecticut was later destroyed on September 21, due to the storm.[13][16] Elsewhere in the state, the winds damaged & destroyed many churches, houses and buildings. Moderate crop damage to fruit was reported as well. The strong winds extended into eastern Massachusetts as well, though little damage was reported in the Boston area.[11] Hurricane-force winds reached as far north as Maine.[2]

Historical context

In 2014, the Swiss Re insurance company estimates that a modern-day hurricane of with the exact track would cause $107 billion (2014 USD) in direct property damage. Damage would total over $1 billion in each of Atlantic (NJ), Ocean (NJ), New Haven (CT), & Hartford (CT) county. Damage would also reach over $2 billion in each Nassau (NY), Suffolk (NY), and Fairfield county in Long Island & Connecticut. Indirect losses, including lost tax revenue + lower real estate would reach near $250 billion nationwide after a similar storm; or ~$332 Billion (2024 USD) when including inflation. The damage would be far greater than what occurred during Hurricane Sandy in 2012, which caused $68.7 billion (2012 USD) in damage when it struck New Jersey.[2][17]

See also

- List of North Carolina hurricanes (pre-1900)

- List of New Jersey hurricanes

- List of New York hurricanes

- List of New England hurricanes

- List of Delaware hurricanes

References

- ^ a b F.P. Ho. "The Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane – Sept. 3-4 – Pt. 2" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ a b c d "Chilling insurance company report: Forget Hurricane Sandy, worst is yet to come". Shore News Today. September 29, 2014. Archived from the original on 2018-04-02. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- ^ a b c Donnelly, Jeffrey P.; et al. (2001). "Sedimentary evidence of intense hurricane strikes from New Jersey". Geology. 29 (7): 615–618. Bibcode:2001Geo....29..615D. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(2001)029<0615:SEOIHS>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Chenoweth (2006). "A Reassessment of Historical Atlantic Basin Tropical Cyclone Activity, 1700-1855" (PDF). NOAA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ Bossak (2003). "Early 19th Century U.S. Hurricanes: A GIS Tool and Climate Analysis". Florida State University. Retrieved 2007-07-02.

- ^ a b c d e David Roth & Hugh Cobb (2001). "Early Nineteenth Century Virginia Hurricanes". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ^ a b c d e David Ludlum. "The Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane – Sept. 3-4 – Pt. 1" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ Alexander Lane (2005). "What if it happened here?". New Jersey Star Ledger. Archived from the original on 2007-09-28. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ Protectingnewjersey.org (2006). "New Jersey: Exposed and Unprepared". Archived from the original on 2006-09-01. Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ a b James B. Elsner. "Annotated Map around NYC of The Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane of 1821 - Sept. 3-4 - Pt. 2" (PDF). fsu.edu. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ a b c David Ludlum. "The Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane – Sept. 3-4 – Pt. 3" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ a b Cotterly (1999). "1821 New England Hurricane" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-04.

- ^ a b c d e f David Ludlum. "The Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane – Sept. 3-4 – Pt. 2" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ^ Aaron Naparstek (2005-07-20). "The Big One for New York City". The New York Press. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ New York City Office of Emergency Management. "Early New York Hurricanes". Archived from the original on 17 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ D'Entremont, Jeremy. The Lighthouses of Connecticut. Commonwealth Editions. pp. 49–53.

- ^ Costliest U.S. tropical cyclones tables updated (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2018.