159th Rifle Division (1943-1946)

| 159th Rifle Division (May 18, 1943 – July 1946) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1943–1946 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Engagements | Smolensk operation Orsha offensives (1943) Operation Bagration Vitebsk–Orsha offensive Minsk offensive Gumbinnen Operation Vistula-Oder Offensive East Prussian Offensive Heiligenbeil Pocket Samland offensive Soviet invasion of Manchuria Harbin–Kirin Operation |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Vitebsk |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. Demyan Iosifovich Bogaychuk Col. Emilyan Fyodorovich Syshchuk Col. Ivan Semyonovich Pavlov Maj. Gen. Nikolai Vasilevich Kalinin |

The third 159th Rifle Division was formed as an infantry division of the Red Army in May-June 1943 in the Moscow Military District based on the 49th Ski Brigade. At this time it was part of the 68th Army in the Reserve of the Supreme High Command, but this Army was assigned to Western Front in July, prior to the summer offensive toward Smolensk. Once that city was liberated in late September the 159th advanced to the west along the highway to Orsha, but found itself involved in a series of largely fruitless battles against German 4th Army's forces through the autumn. After 68th Army was disbanded the attentions of the Front were largely redirected toward Vitebsk during equally dismal and grinding combat through the winter. During this period it was assigned to 5th Army's 45th Rifle Corps and it would continue under these two commands into the postwar years. When Western Front was split during the spring of 1944 5th Army became part of 3rd Belorussian Front. Vitebsk was finally taken in the early days of the summer offensive, Operation Bagration, and the 159th, as well as one of its regiments, were awarded its name as a battle honor. As the offensive expanded the division raced, with its Front, into southern Lithuania and in the process distinguished itself in the battle for Vilnius, for which it was awarded the Order of the Red Banner. In late July it helped to force the German defenses along the Neman River and was soon decorated with the Order of Suvorov, while two of its regiments also received distinctions. After taking part in the failed October advance into East Prussia the 159th remained along the German border until January 1945 and the decisive Vistula-Oder offensive. It broke through the defenses that had held it at bay the previous autumn, then pushed through past Königsberg, which was besieged into April. During that month the division saw action in clearing Samland, then loaded on trains as part of the Reserve of the Supreme High Command, moving across the USSR to take part in the invasion of Manchuria. It received the Order of Kutuzov following this operation, and remained in the far east until July 1946, when it was disbanded along with the rest of 45th Corps.

Formation

The 132nd Rifle Brigade had been formed between December 1941 and March 1942 in the Ural Military District before being sent to 30th Army in Kalinin Front in April. It remained under these commands into August when it was transferred with its Army to Western Front. The following month the Army began to reorganize the unit as the 49th Ski Brigade in preparation for the expected winter offensive (Operation Mars). As with the several other ski brigades formed in the Front’s armies at this time, the 49th was intended to act as a forward detachment in the event of mobile operations. Mars failed in this and most other respects and the 49th was not committed. In December all or most of the Army’s various ski units were consolidated under its command and by the end of the year it consisted of:

- 6 ski battalions, each:

- 6 ski companies

- 1 light machine gun company

- 1 artillery battalion

- 1 heavy machine gun company (9 HMGs)

- 1 antitank rifle company

- 1 sapper company

- 1 signal company

This gave it nearly three times the strength of a typical ski brigade of the time. Since the front remained relatively quiet in this sector during the rest of the winter the 49th likely remained out of the line. By April 1943 it was under command of 31st Army,[1] still in Western Front.[2]

The new 159th began forming on May 18 with its headquarters at Stary Rukav, Rzhevsky District, Tver Oblast, in the Moscow Military District, as part of 68th Army. It was based on the 49th Brigade as well as the second formation of the 20th Rifle Brigade.[3] Its order of battle, similar to that of the previous formations, was as follows:

- 491st Rifle Regiment

- 558th Rifle Regiment

- 631st Rifle Regiment

- 597th Artillery Regiment

- 136th Antitank Battalion[4]

- 498th Self-propelled Artillery Battalion (from August 9, 1945)

- 243rd Reconnaissance Company

- 185th Sapper Battalion

- 460th Signal Battalion (later 150th Signal Company)

- 207th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 139th Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Company

- 206th Motor Transport Company

- 445th Field Bakery

- 910th Divisional Veterinary Hospital

- 1667th Field Postal Station

- 1623rd Field Office of the State Bank

Col. Demyan Iosifovich Bogaychuk, who had been in command of the 20th Brigade, took command of the division when it began forming. Lt. Col. Emilyan Fyodorovich Syshchuk was made deputy commander and chief of staff; he had served in the latter role in the 49th Brigade. The combined strength of the two brigades was 7,721 personnel (of 32 various nationalities), including 835 officers. The 159th arrived at the active front on July 12 and it was assigned to the 62nd Rifle Corps, along with the 153rd and 154th Rifle Divisions.[5]

Battle of Smolensk

Operation Suvorov began on August 7 with a preliminary bombardment at 0440 hours and a ground assault at 0630. The commander of Western Front, Col. Gen. V. D. Sokolovskii, committed his 5th, 10th Guards, and 33rd Armies in the initial assault, while 68th Army was in second echelon. The attack quickly encountered heavy opposition and stalled. By early afternoon, Sokolovskii became concerned about the inability of most of his units to advance and decided to commit 68th Army's 81st Rifle Corps to reinforce the push by 10th Guards Army against XII Army Corps. This was a premature and foolish decision on a number of levels, crowding an already stalled front with even more troops and vehicles.[6]

On the morning of August 8, Sokolovskii resumed his offensive at 0730 hours, but now he had three armies tangled up on the main axis of advance. After a 30-minute artillery preparation the Soviets resumed their attacks across a 10km-wide front. 81st Corps was inserted between the two engaged corps of 10th Guards, putting further pressure on the 268th Infantry Division. Reinforcements from 2nd Panzer Division were coming up from Yelnya in support. By August 11 it became clear that XII Corps was running out of infantry and so late in the day the German forces began falling back toward the Yelnya–Spas-Demensk railway. By now Western Front had expended nearly all its artillery ammunition and was not able to immediately exploit the withdrawal. Sokolovskii was authorized to temporarily suspend Suvorov on August 21.[7]

Yelnya Offensive

Sokolovskii was given just one week to reorganize for the next push. In the new plan the 10th Guards, 21st, 33rd and 68th Armies would make the main effort, attacking XII Corps all along its front until it shattered, then push mobile groups through the gaps to seize Yelnya. It kicked off on August 28 with a 90-minute artillery preparation across a 25km-wide front, but did not initially include 68th Army. A gap soon appeared in the German front in 33rd Army's sector, and the 5th Mechanized Corps was committed. On the second day this Corps achieved a breakthrough and Yelnya was liberated on August 30. By this time the attacking rifle divisions were reduced to 3,000 men or fewer.[8] By the beginning of September the 159th had left 62nd Corps and was under direct Army command.[9]

Advance to Smolensk

The offensive was again suspended on September 7, with one week allowed for logistical replenishment. When it resumed on September 15, German 4th Army was expected to hold a 164km front with fewer than 30,000 troops. Sokolovskii prepared to make his main effort with the same four armies against IX Army Corps' positions west of Yelnya; the Corps had five decimated divisions to defend a 40km-wide front. At 0545 hours a 90-minute artillery preparation began, followed by intense bombing attacks. When the ground attack began the main effort was directed south of the Yelnya–Smolensk railway, near the town of Leonovo. After making gains the attacks resumed at 0630 on September 16. 68th Army continued probing attacks against 35th and 252nd Infantry Divisions, and although the IX Corps was not broken after two days, it was ordered to withdraw to the next line of defense overnight on September 16/17. Sokolovskii intended to pursue the left wing of the Corps and approach Smolensk from the south with the 68th, 10th Guards, and most of his armor.[10]

By September 18, the 4th Army was falling back to the Hubertus-II-Stellung with Western Front in pursuit. On paper, this line offered the potential to mount a last-minute defense of Smolensk, but only very basic fieldworks actually existed. By now IX Corps was a broken and retreating formation. In the event, the converging Soviet armies had to pause for a few days outside the city before making the final push. On the morning of September 22 the 68th Army achieved a clear breakthrough south-east of Smolensk, in the sector held by remnants of 35th Infantry. By the next morning it was clear that the Hubertus-III-Stellung could not be held. The commander of 4th Army made preparations to evacuate the city. During the afternoon of September 24 the 72nd Rifle Corps pushed back the 337th Infantry Division. Sokolovskii knew that 4th Army was not likely to fight for Smolensk and he wanted the city secured before it was completely destroyed. At 1000 hours the next day that Corps advanced into the southern part of the city and linked up with units of 5th and 31st Army. 4th Army fell back to the Dora-Stellung overnight on September 26/27. The onus of pursuit along the Minsk–Moscow Highway fell on the 5th and 68th Armies as more battle-weary armies were pulled out of the line to regroup.[11]

Orsha Offensives

By October 3, 68th Army had reached a front extending from the southern bank of the Dniepr south of Vizhimaki south along the Myareya River to Lyady. The 192nd and 199th Rifle Divisions of 72nd Corps, plus the 159th and the 6th Guards Cavalry Division attacked the German positions at Filaty on the Myareya. The 18th Panzer Grenadier Division was overextended and hard-pressed, and when, late on October 8, the 159th and 88th Rifle Divisions assaulted across the river it was forced westward. Pursued by forward detachments of the Army's lead divisions the panzer grenadiers took up new positions on October 11 along the Rossasenka River. The 68th prepared to resume its assaults on October 12, but due to transfers to 31st Army it was now reduced to just three divisions (192nd, 199th, 159th).[12]

Second Orsha Offensive

Encouraged by some modest successes along the Smolensk–Orsha road, Sokolovskii ordered his forces to resume operations early on October 12. The three divisions of 68th Army were tasked with defending the left flank of 31st Army, south of the Dniepr. The attack began with an artillery preparation which the German forces were expecting; falling back to the second line of trenches they escaped any significant casualties and the offensive faltered almost immediately. Fighting continued until October 18 but the gains were no more than 1,500m at the cost to the Front of 5,858 killed and 17,478 wounded. The operation was renewed early on October 21 after the artillery had fired for two hours and ten minutes. The 159th forced a crossing of the Rossasenka River and advanced 500m, closing to Height Marker 180.8 before being halted by heavy fire. German artillery from the heights now dropped a barrage to prevent Soviet reinforcements from crossing. The division faced counterattacks from 1st SS Brigade during the next two days which finally forced the Army command to issue withdrawal orders to Bogaychuk, but he was unable to comply.[13]

At about this time the 159th joined the 192nd and 174th Rifle Divisions in the 72nd Rifle Corps.[14] Overnight on October 24/25 the 174th moved along the north bank of the Dniepr before using the cover of darkness and Corps artillery fire to make a crossing in small boats. It then attacked through the 159th to capture Height 180.8 by the end of October 26 before throwing back up to 11 counterattacks. Sokolovskii suspended his offensive again on the same date, after a further 19,102 casualties.[15] On November 5 the 68th Army was disbanded and 72nd Corps went to 5th Army.[16] The division would remain in this Army into the postwar era.[17]

Fourth and Fifth Orsha Offensives

Sokolovskii submitted his plan for a renewed offensive to the STAVKA on November 9. The second shock group would be made up of 5th and 33rd Armies in triple-echelon formation attacking south of the Dniepr toward Dubrowna and Orsha. It was to begin on November 14 following a three-an-a-half artillery and air preparation. The overall offensive front was 25km-wide and 72nd Corps faced the 1st SS. When it began the Corps was led by the 174th and fought successfully until its assault faltered on the northern approaches to Bobrovna. The assault was renewed the next day but Bobrovna and the heights west of the Rossasenka continued to hold out, largely because of determined counterattacks in battalion strength. The fighting continued for three more days in the face of stiffening German resistance. Finally, by committing the fresh 144th Rifle Division a 10km-wide and 3-4km-deep bridgehead over the Rossasenka had been driven by the end of November 18. This was one of the deepest penetrations made during the offensive, which cost a further 9,167 killed and 28,589 wounded among the four armies involved.[18] On November 22 Colonel Bogaychuk left the division on orders to further his military education, and attended the Voroshilov Academy beginning in January 1944, but was unable to complete his courses due to poor health. In April he was made head of the Infantry School at Ulyanovsk, and he was retired from service in February 1946. Lt. Col. Syshchuk took over command of the 159th until December 6 when Col. Vasilii Aleksandrovich Kalachyov arrived from the staff of 10th Guards Army.

A fifth offensive took place from November 30 until December 5, through wet snow that turned the roads into slurry. Elements of 5th Army finally managed to seize Bobrovna on December 2 but German reserves prevented any further advance. By now the Army's divisions varied from 3,088 to 4,095 personnel. Following these successive failures Sokolovskii soon ordered his forces to regroup to the north to join 1st Baltic Front in a fresh effort to take Vitebsk.[19]

Battles for Vitebsk

On December 23 Western Front's 33rd Army, massively reinforced, and the 39th Army of 1st Baltic Front, began a new drive from east and northeast of Vitebsk that was expected to crack the defenses of 3rd Panzer Army and capture the city. Two days later elements of 33rd Army cut the Smolensk–Vitebsk at a point just 20km southeast of the latter city's central square. Over the following week the advance continued at a steadily decreasing pace, and on January 1, 1944, Sokolovskii issued orders to 5th Army's commander, Lt. Gen. N. I. Krylov, to move the 72nd Corps (153rd, 159th, 277th Rifle Divisions), to move to assault positions between the villages of Krynki and Maklaki to reinforce the left flank of 33rd Army. At the same time, Krylov received the 45th Rifle Corps plus the 157th Rifle Division and 36th Rifle Brigade to bolster his forces. 72nd Corps formed the second shock group when the offensive resumed, with the 159th and 153rd in first echelon. They were to advance to the southwest, take Drybino and Krynki, cut the highway between Vitebsk and Orsha, and cover 33rd Army's flank.[20]

Krylov recorded the offensive in his memoirs:

Five rifle divisions and three tank brigades participated in the offensive 5th Army undertook during the beginning of January 1944. They were supported by artillery from 81st and 72nd Rifle Corps. The sharpest fighting developed in the sectors of understrength 159th Rifle Division and 36th Rifle Brigade.

Plentiful snow began falling on that morning, and soon after a blizzard began. All of the regiments went over to the attack and skillfully forced their way across the thick ice on the Lososina River [which blocked the advance on Drybino]. All the routes were covered [with snow] and it was impossible for either the infantry or tanks to advance further. The attack advanced no further than a kilometre during the day.

The division and the brigade managed to reach the northern outskirts of Drybino and to take the strongpoint at Krynki from the 246th Infantry Division, but then ran into the 245th Assault Gun Detachment which, along with the weather, halted further progress. By late on January 6 Sokolovskii was granted a temporary halt.[21]

The STAVKA ordered the offensive to be renewed on January 8. 72nd Corps was tasked with widening the penetration and guarding the flank of 33rd Army. The Corps faced a 7km wide sector from Maklaki east to Miafli with the 159th and 153rd Divisions, plus 36th Brigade, in first echelon, supported by the 213th and 256th Tank Brigades, and the 277th Division in second echelon. Still opposed by the 246th Infantry, the objectives were strongpoints at Dymanovo, Drybino and Krynki, 2-4km from the start line, followed by an exploitation to the southwest to the Vitebsk–Orsha road. By now, all of Sokolovskii's divisions and tank brigades were under 40 percent strength. In two days of heavy fighting the Corps broke the defenses of part of the Feldherrnhalle Panzergrenadier Division, crossed the road, captured Dymanovo, and reached the approaches to Sheliai, 4.5km into the German defenses. By late on January 10 it appeared that 5th and 33rd Armies had created conditions for the commitment of 2nd Guards Tank Corps, if a crossing could be forced over the Luchesa River, just 1,000m farther on. However, German reserves were rapidly arriving, blocking any advance beyond Sheliai, and the Corps made no further progress over the next five days. By the end of January 14 the offensive was burned out, with the divisions down to 2,500 - 3,500 personnel each.[22]

Despite the weakness of his forces, Krylov stated later:

Undoubtedly, the seizure of the Vitebsk-Orsha main road was a major success. At the same time, this situation created certain complications since the enemy continued to hold on to the region around the village of Krynki, situated 5 kilometres east of Dymanovo, which was occupied by our forces. By doing so, he threatened 5th Army's entire left wing with a penetration to the north in the direction of Eremino, which, if carried out, could force our forces to withdraw behind the line of the Vitebsk-Smolensk railroad.

Thus, the mission of improving its position now gained far greater importance for 5th Army since only by doing so could we prevent an enemy penetration to the north.

He therefore prepared a new offensive to take place on January 15, to the south toward Krynki. Reinforcements from 33rd Army were transferred to 72nd Corps, in addition to several tank corps. Krylov designated his shock group as the 159th, 199th, and 157th Divisions in first echelon on a 6km-wide sector, with 173rd and 222nd Rifle Divisions plus 36th Rifle Brigade in second. Krylov described the outcome as follows:

[I] proposed to throw the enemy back to the south beyond the Sukhodrovka River with an attack by the 159th and 199th Rifle Divisions and, by doing so, to protect the army's left wing. In the event of success, we also intended to capture Vysochany [28 kilometres south-southeast of Vitebsk] where the enemy had created a strongpoint...

The offensive began on the night of [14-15 January]. It turned bitterly cold, and a blizzard left heavy snow cover and prevented observation of the enemy's positions in the Krynki region. But neither the weather nor the enemy fire stopped the attacking units of 159th and 199th Rifle Divisions and 2nd Guards Tank Corps' 26th Tank Brigade.

This brigade had already contributed to the success of 5th Army's rifle divisions many times... [The 159th Rifle Division and 26th Tank Brigade had conducted a successful night attack on Hill 189.6 and the village of Shevdy, which the Hitlerites had turned into a strongpoint after expelling its inhabitants.] Our subunits threw the enemy out of their first and second trenches but were able to advance no further.

In subsequent battles our units pressed the enemy back further and captured the village of Cherkasy, which had also been converted by them into a strongpoint. But we were not able to hold on to it at this time (it was liberated somewhat later), and, in the end, we dug in 400-500 metres north of Hill 189.6.

After several days of heavy fighting the shock group had taken Krynki and gained about 2km east of that place, but Miafli and a section of the railroad remained in German hands when the effort was halted on January 20. Sixteen days of battle had cost Western Front another 25,000 casualties, 5,500 of whom were killed, for a gain of no more than 4km.[23] On January 29 Colonel Kalachyov was removed from his command "due to inadequacy" and soon appointed commander of the 563rd Rifle Regiment of the 153rd Rifle Division. Syshchuk, who had been promoted to full colonel, replaced him until March 12 when Col. Ivan Semyonovich Pavlov took over the post.

The Arguny Salient

Sokolovskii was now ordered to shift the axis of his attacks northward toward Vitebsk itself. At the beginning of February the 159th facing elements of the 211th Infantry Division on the south side of the so-called Arguny salient south and east of Vitebsk, still in the Krynki area, and so away from the new axis. Along with the 153rd Division it was designated for a diversionary attack which began early on February 2, just as 1st Baltic Front began a major assault from north and west of Vitebsk. The attack advanced less than 1,000m on the first day and failed to make an impression on the German command.[24] Later in the month the division was transferred to 45th Corps, joining the 184th and 338th Rifle Divisions.[25] The division would remain in this Corps until it was disbanded.[26]

The STAVKA now ordered Sokolovskii to prepare yet another offensive against Vitebsk to begin in March, and he in turn proposed a preliminary operation southeast of the Arguny salient to begin on February 22. 45th Corps would form the 5th Army shock group, striking to the west from south of the Sukhodrovka River at Marianovo in an effort to outflank the 211th Infantry at Vysochany. A further shock group from 31st Army would also be involved to the south. Western Front assumed that German forces in the sector had been weakened to deal with the fighting along the Luchesa. 45th Corps, on the left wing of 5th Army, was assigned a 3km-wide sector between Marianovo and Rubleva, and was to push through the left wing of the 256th Infantry Division, take the strongpoints at Rubleva and Kazimirovka, before continuing to Osinovka and the Vitebsk–Orsha road. The 184th and 338th Divisions would lead, supported by elements of the 159th.[27]

On the first day the lead divisions successfully penetrated the 211th Infantry between Kosteevo and Rubleva to a depth of about 1,000m but were halted to the east of Kazimirovka. The assault by the 159th south of Marianovo failed completely, largely due to the arrival of the 406th Grenadier Regiment of the 201st Security Division. The fighting was soon brought to a halt. During February, Western Front suffered a total of 71,689 casualties, most of them in 33rd and 5th Armies. A report from late in the month put the personnel strength of the 159th at 3,450.[28]

Bogushevsk Offensive

Yet another offensive on this sector was planned to begin on March 21. At this time the division was in the center of the Corps sector on the Army's left wing. According to the plan the Front's shock group was to penetrate the defense between Drybino and Dobrino prior to pushing south some 5-10km to the Sukhodrovka. It was then to push the German forces back to the upper reaches of the Luchesa and create bridgeheads; this would require a total advance of about 15km. If this was successful the 45th Corps would join the push with a supporting attack from the Leutino area, held by the 159th, and then also reach the Luchesa.[29]

The Corps had by now replaced the 184th with the 157th Division. The latter shifted to the left to make room for the main shock group, then concentrated with the 159th in the Belyi Bor area to prepare for their follow-up attack. They were still facing the 406th Grenadier Regiment, plus a battalion of the 14th Infantry Division, and were deployed on a 2km-wide front. The main offensive began after an intense artillery preparation, and its weight broke the defense on a wide sector, with an advance of between 1-4km on the first day. However, 3rd Panzer Army reacted quickly with reserves, which largely halted the advance. On either March 24 or 25, now in an effort to restore the offensive, the 159th and 157th struck southwest of Dobrino against the 406th Regiment, which had already sent part of its forces west to battle the main shock group. They penetrated as much as 2km and took Kukharevka, but another quick reaction held the Soviet divisions short of Dobrino and Vysochany. By March 27 it was clear that the offensive had failed, although the fighting went on for another two days. Casualties were again high, totaling 57,861 in Western Front during March, again mostly from 5th and 33rd Armies.[30]

Operation Bagration

This scale of bloodletting, especially for such meager results, was more than the Red Army could sustain, and within two weeks Stalin had dismissed Sokolovskii. Western Front was split into the new 2nd and 3rd Belorussian Fronts, with 5th Army going to the latter.[31] On May 30, Colonel Pavlov was hospitalized due to ongoing effects of severe leg wounds suffered in October 1943, and he would later join the educational establishment for the duration. Col. Vasilii Filippovich Samoylenko took over on June 3, with Colonel Syshchuk continuing to serve as his deputy. On June 9 the latter was mortally wounded by mortar fire and died on June 16. On the previous day Colonel Samoylenko was also wounded while on reconnaissance and evacuated to hospital; he did not return to the front. Maj. Gen. Nikolai Vasilevich Kalinin took command on June 16, coming directly from the Voroshilov Academy. This officer had previously led the 91st Rifle Division before being wounded and hospitalized in July 1943. He would remain in command until early 1946. Prior to the offensive, Kalinin was assigned the 336th Penal (Straf) Company, which would serve as an assault unit.[32]

Vitebsk–Orsha Offensive

3rd Belorussian Front was under command of Col. Gen. I. D. Chernyakhovskii. For the offensive he had, on his right (north) wing, the 39th Army and 5th Army, with the 5th Guards Tank Army in reserve.[33] 5th Army was still largely in the positions south and southeast of Vitebsk that it had won at such cost through the winter. Chernyakhovskii's plan for the first phase of the offensive was to defeat the opposing forces of Army Group Center and reach the Berezina River before developing the advance toward Minsk. This would begin with two attacks: the first from west of Lyozna toward Bahushewsk and Syanno; the second from northeast of Dubrowna along the Minsk highway in the direction of Barysaw. The 5th and 39th would carry out the first of these. Their task was to break the defense on a 18km-wide sector from Karpovichy to Vysochany, after which Krylov's forces, backed by Oslikovsky's Cavalry-Mechanized Group, would drive on Bahushewsk and encircle the 3rd Panzer Army in cooperation with the left wing of 1st Baltic Front. Specifically, Chernyakhovskii ordered Krylov to attack with two rifle regiments of the 159th in the direction of Babinavichy to link up with 11th Guards Army's 152nd Fortified Region, with the objective of destroying the German grouping in the Osetki–Makeevo–Sleptsy area.[34]

After a 2-hour-and-20-minute artillery preparation and attacks from the air, 5th Army, deployed on a 30km front, kicked off its assault on the afternoon of June 22. The 159th led 45th Corps, with the 184th and 338th following. The German 256th Infantry was defending, with elements of the 95th Infantry Division in reserve. On the first day the attackers broke through the immediate German defenses and began charging westward. By noon on June 23 the 5th Army had turned southwards and began crossing the Luchesa River; by midnight it was only 13km from Bahushewsk. On the morning of June 24 the German VI Army Corps was still holding a line about 10km east of Bahushewsk, but this was soon broken, with Soviet tanks entering the town at noon with infantry following. 45th Corps, with the 159th in the lead, reached there early on June 26, continuing to advance towards Syanno. By the end of June 27 the division was well past there and had reached Cherekhya, not far from Lake Lukomlskoye.[35] In recognition of this victory and the months'-long struggle that preceded it, the division, plus one of its regiments, were given a battle honor:

VITEBSK – ... 159th Rifle Division (Major General Kalinin, Nikolai Vasilevich)... 631st Rifle Regiment (Lt. Colonel Dmitriev, Kirill Dmitrievich)... The troops who participated in the liberation of Vitebsk, by the order of the Supreme High Command of 26 June 1944 and a commendation in Moscow are given a salute of 20 artillery salvoes from 224 guns.[36]

On the morning of June 29 the division, along with the 215th Rifle Division, were still at Lukomlskoye, holding the gap for four mobile columns of 3rd Guards Mechanized Corps as they pushed toward Maladzyechna, well to the German rear.[37] In the fighting between June 26-28, 45th Corps was estimated to have killed 1,500 German personnel and captured 2,500 more.[38]

Minsk Offensive

The next objective was to exploit the several breakthroughs and complete the destruction of Army Group Center. 1st Baltic and 3rd Belorussian Fronts were to press into Lithuania (the "Baltic Gap") and north of Minsk respectively. The main forces of 5th Army reached the Vilnius area on July 8. Along with 3rd Guards Mechanized and elements of 5th Guards Tank Army, street fighting for the city began at 0700 hours. At the same time other units of the Front were moving up to the north and southwest, cutting the rail lines to Kaunas, Grodno, and Lida. The Vilnius garrison was now enveloped on three sides, and over the following day the 3rd Panzer Army desperately fought to keep communications open. 45th Corps was involved in a stubborn fight for Landvorovo southwest of the city. The garrison was completely isolated on July 10 and its remnants took refuge near the observatory and the old citadel. Late on that day the attack on Landvorovo was joined by 29th Tank Corps and the place was taken jointly with the 184th Division on July 11. The next day the main forces of 5th Army drove forward 10-12km, but 45th Corps was held up by stubborn resistance some 4km northwest of Landvorovo from Group "Tolendorf" (based on 12th Panzer Division) which was still trying to meet up with the encircled garrison. This was partially successful, although Vilnius itself was cleared by 1700 on July 13. Following this, the Front's center and left wing advanced rapidly to the Neman River.[39] On July 25 the 159th would be awarded the Order of the Red Banner for its part in this victory.[40]

Kaunas and the Neman

The STAVKA issued Directive No. 220160 on July 28, which ordered Chernyakhovskii to develop the offensive with his 5th and 39th Armies and take Kaunas by August 1-2 through a converging attack from north and south; following this his Front was to drive across the border of East Prussia, taking the line Raseiniai–Suwałki as a start line. The general offensive began at 0840 hours on July 29 after a 40-minute air and artillery preparation. The 5th, 33rd, and 11th Guards Armies led off, penetrating the defense up to 15km, although 5th Army's left flank advanced just 5-7km along its bridgehead on the west bank of the Neman. The next day saw German resistance along the river largely collapse; forces of the Front advanced on Vilkaviškis, and 45th Corps conducted a pursuit south of the Neman during July 30-31. Kaunas itself was cleared by 5th Army forces by 0700 on August 1.[41] The 491st Rifle Regiment would receive the honorific "Neman", while on August 12 the division as a whole would be presented with the Order of Suvorov, 2nd Degree, and the 631st Regiment was decorated with the Order of Alexander Nevsky, in both cases for the forced crossings of the river.[42]

On August 17 the 558th Rifle Regiment was one of the first Red Army infantry units to reach and cross the prewar frontier with Germany, in the vicinity of Kudirkos Naumiestis. The following day it faced several counterattacks by infantry backed by 17 tanks and six assault guns, but held its ground. On March 24, 1945, the regimental commander, Lt. Col. Mikhail Evdokimovich Volkov, would be one of about 14 soldiers of the division to be made Heroes of the Soviet Union for this symbolic achievement.[43]

In mid-October the 5th and 11th Guards Armies led the rest of 3rd Belorussian Front in the abortive Goldap-Gumbinnen operation into East Prussia. On November 14 the 558th Regiment was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for its part in this offensive.[44]

East Prussian Offensives

At the beginning of the new year the 45th Corps had the 159th and 184th Divisions under command,[45] but the 157th soon rejoined it. At the start of the Vistula-Oder Offensive on January 12, 5th Army was tasked with a vigorous attack in the direction of Mallwischken and Gross Skeisgirren, with the immediate task of breaking through the defense, then encircling and destroying the Tilsit group of forces in conjunction with the 39th Army. Progress proved slower than expected, with the German forces putting up fierce resistance. On the morning of January 14, 5th Army broke through the enemy's fourth trench line, and began to speed up the advance until the early afternoon, when heavy German counterattacks began. 65th Corps faced tank and infantry attacks from the 5th Panzer Division, which slowed, but did not halt, the advance. This sped up considerably on January 17 as 2nd Guards Tank Corps took up the running. 45th and 65th Corps had taken and consolidated the strongpoint of Radschen before advancing to a line from Mingschtimmen to Korellen, throwing the defenders out of the main positions of their Gumbinnen defense line. The last German reserves, including the 10th Motorized Brigade of nine assault gun companies, struck the boundary of the 45th and 72nd Corps before a fighting withdrawal to the west began.[46] On February 19 the 491st Rifle and 597th Artillery Regiments would both receive the Order of the Red Banner for breaking the East Prussian defenses.[47]

Despite these breakthroughs a core group of German forces continued to hold out against 5th and 28th Armies in the Gumbinnen–Insterburg area. Krylov moved part of his 72nd Corps forces northward to attack in the Girren area, but this did not prove effective. 45th Corps joined this effort and advanced slowly with the 72nd and by 2100 hours the joint force had taken the defense line along the Tilsit–Gumbinnen paved road, moving up to the line Kraupischken–Neudorf–Antballen. 5th Army was ordered early on January 20 to push on to reach the Angerapp and Pissa Rivers with its main forces by the end of the day. On January 21, the Army was directed to encircle and destroy the German grouping defending Insterburg in conjunction with 11th Guards Army on the following day; 45th Corps was to attack towards Didlakken. By 0600 hours on January 22 Insterburg had been completely cleared. During the following week the Army continued to attack in the direction of Zinten.[48]

On January 27, 45th Corps, attacking along the Army's right flank, reached the area of Uderwangen and turned to the southwest toward Preußisch Eylau, with 72nd Corps following. By this time most German forces in East Prussia were falling back toward Königsberg and its fortifications. The following morning the 45th was unexpectedly counterattacked by elements of XXVI Army Corps coming from the south. The German force included up to 35 tanks and assault guns, but was thrown back with losses. The 45th now pushed the attackers back to the south, forced a crossing of the Frisching River, and reached a line from Mühlhausen to Abswangen by the end of the day. Krylov exploited this success by committing 72nd Corps from behind the right flank toward Kreuzburg. On January 29 the 65th Corps turned its sector north of Friedland over to 28th Army and was moved to the left flank of 45th Corps before also beginning an attack to the south. The German forces continued to resist along the Heilsberg fortified line, and it was not until February 7 that 5th Army's forces were able to secure Kreuzburg.[49] By March 12 the 159th was noted as having just 2,541 personnel on strength.[50] On April 5 the 597th Artillery Regiment would be decorated with the Order of Kutuzov, 3rd Degree, for its role in the capture of Heilsberg and Friedland.[51]

Samland Offensive

By the start of April the Soviet forces had been significantly regrouped. 5th Army was holding a sector from Spallwitten to Reessen, southwest of Königsberg. The Army was not part of the Zemland Group of Forces and was therefore not tasked with taking part in the assault on the city, which was set to begin on April 6. Instead, it would take part in the mopping up of the German forces isolated in the Sambia Peninsula, which began on April 13. The 5th and 39th Armies were assigned to make the main attack in the direction of Fischhausen, which would split XXVIII Army Corps in half east to west. Following this, the northern and southern pockets would be defeated in detail, with the assistance of 43rd and 2nd Guards Armies. The attack began with an hour-long artillery preparation before the infantry advanced at 0800 hours. 5th Army, on the right flank, moved on Norgau and Rotenen, advanced 5km, and took more than 1,000 prisoners. A further 3km were gained the next day against stubborn resistance. By April 17 the entire peninsula had been cleared, and 5th Army was already being pulled out of the fighting.[52] While it moved back to the nearest railheads, the Army was assigned to the Reserve of the Supreme High Command on April 19 as it entrained for the far east.

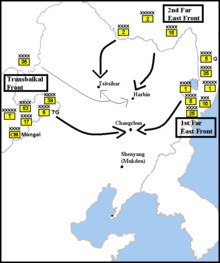

Soviet invasion of Manchuria

During this movement the 159th was brought up closer to full strength, and was also assigned the 498th Self-propelled Artillery Battalion of 20 SU-76s (plus one T-70 command tank), as was done with many of the rifle divisions assigned to the far eastern theatre. By the end of June it was in the Maritime Group of the Far Eastern Front, which became the 1st Far Eastern Front at the beginning of August.[53] When the offensive began on August 9 the 5th Army was tasked with making the Front's main attack. By day's end the Army had torn a gap 35km wide in the Japanese lines and had advanced anything from 16-22km into the enemy rear, with 45th Corps in second echelon. Within three days the rifle regiments of the Corps' three divisions, backed by reinforcing sappers and their new self-propelled artillery, had liquidated all remaining strongholds in Volynsk, Suifenho, and Lumentai. The Army's other three corps advanced deep into Japanese-held territory against the retreating 124th Infantry Division. Mudanjiang was taken after a two-day battle on August 15-16, following which 5th Army pushed southwestward towards Ning'an, Tunghua and Kirin. On August 18 the Japanese capitulation was announced, and the Army deployed to accept and process the surrendering units.[54]

Postwar

On September 19 the division gained its final decoration, the Order of Kutuzov, 2nd Degree, for its service against Japan, while the 558th Regiment received the same Order in the 3rd Degree.[55] The men and women of the division now shared the full title of 159th Rifle, Vitebsk, Order of the Red Banner, Order of Suvorov and Kutuzov Division. (Russian: 159-я стрелковая Витебская Краснознамённая орденов Суворова и Кутузова дивизия.) The division was disbanded in 1946 with the remainder of 45th Corps.[56] General Kalinin had left his command in January 1946; he was first placed at the disposal of the Main Personnel Directorate, then assigned as a military commissar in the Sumy area until his retirement in November 1953. He died in Moscow on March 17, 1970, and was buried in Sumy.

References

Citations

- ^ Charles C. Sharp, "Red Volunteers", Soviet Militia Units, Rifle and Ski Brigades 1941 - 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. XI, Nafziger, 1996, pp. 61, 94-95

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 108

- ^ Walter S. Dunn Jr., Stalin's Keys to Victory, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2007, p. 132

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed From 1942 to 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. X, Nafziger, 1996, p. 64

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 188

- ^ Robert Forczyk, Smolensk 1943: The Red Army's Relentless Advance, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2019, Kindle ed.

- ^ Forczyk, Smolensk 1943: The Red Army's Relentless Advance, Kindle ed.

- ^ Forczyk, Smolensk 1943: The Red Army's Relentless Advance, Kindle ed. Note this source states Yelnya was liberated on August 20.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 218

- ^ Forczyk, Smolensk 1943: The Red Army's Relentless Advance, Kindle ed.

- ^ Forczyk, Smolensk 1943: The Red Army's Relentless Advance, Kindle ed.

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2016, pp. 66-67

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 71, 81, 83, 85-86

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 276

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, p. 87

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, pp. 276, 303

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", p. 64

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 156-58, 162-64

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, p. 166

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 291-95, 297-99

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 300-01. The quotation is from N. I. Krylov, N. I. Alekseev, and I. G. Dragan, Greeting victory: The combat path of 5th Army, October 1941-August 1945, Nauka, Moscow, 1970, pp. 175-76.

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 309-10, 319-21, 324

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 324-29. Quotations from Krylov, Alekseev, and Dragan, Greeting victory.

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 349-50, 353

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 70

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", p. 64

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 362-65

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 366-67, 693

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 387, 390

- ^ Glantz, Battle for Belorussia, pp. 393-96, 399-401

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 130

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", p. 64

- ^ Dunn Jr., Soviet Blitzkrieg, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2008, p. 118

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., vol. 1, chs. 3, 4

- ^ Dunn Jr., Soviet Blitzkrieg, pp. 117-31

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-1.html. In Russian. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ Dunn Jr., Soviet Blitzkrieg, p. 133

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, Kindle ed., vol. 2, ch. 3

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, Kindle ed., vol. 2, ch. 8

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 410.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Operation Bagration, Kindle ed., vol. 2, ch. 8

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, pp. 460–61.

- ^ https://warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=13022. In Russian, English translation available. Retrieved February 27, 2025.

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 559.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, p. 11

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, pp. 123, 192-95

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 245.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 218-20, 222-24

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 231-33

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", p. 64

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 52.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 254, 266-69

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1945, pp. 191, 201

- ^ Glantz, August Storm, The Soviet 1945 Strategic Offensive in Manchuria, Pickle Partners Publishing, 2003, Kindle ed., ch. 8

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, pp. 423–24.

- ^ Feskov et al. 2013, p. 579.

Bibliography

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967a). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть I. 1920 - 1944 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part I. 1920–1944] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967b). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть II. 1945 – 1966 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part II. 1945–1966] (in Russian). Moscow.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Feskov, V.I.; Golikov, V.I.; Kalashnikov, K.A.; Slugin, S.A. (2013). Вооруженные силы СССР после Второй Мировой войны: от Красной Армии к Советской [The Armed Forces of the USSR after World War II: From the Red Army to the Soviet: Part 1 Land Forces] (in Russian). Tomsk: Scientific and Technical Literature Publishing. ISBN 9785895035306.

- Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. p. 78

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. pp. 180-81