158th Rifle Division

| 158th Rifle Division (September 15, 1939 – August 18, 1941) 158th Rifle Division (January 20, 1942 - June 1945) | |

|---|---|

| Active | 1939–1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Infantry |

| Size | Division |

| Engagements | Operation Barbarossa Battle of Smolensk (1941) Battle of Moscow Toropets–Kholm offensive Battles of Rzhev Operation Büffel Smolensk operation Orsha offensives (1943) Operation Bagration Baltic offensive Šiauliai offensive Kaunas offensive Courland Pocket East Pomeranian offensive Battle of Berlin |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Liozno Vitebsk (both 2nd Formation) |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. Vitalii Ivanovich Novozhilov Col. Stepan Efimovich Isaev Maj. Gen. Aleksei Ivanovich Zugin Maj. Gen. Mikhail Mikhailovich Busarov Maj. Gen. Ivan Semyonovich Bezuglyi Col. Demyan Ilich Goncharov |

The 158th Rifle Division was originally formed as an infantry division of the Red Army on September 15, 1939 in the North Caucasus Military District, based on the shtat (table of organization and equipment) of that month. After remaining in that District through 1940 it was moving through Ukraine in June 1941 as part of 19th Army when the German invasion began. Shortly after arriving at the fighting front it was pocketed by forces of Army Group Center west of Smolensk, along with most of its Army. The division fought in semi-encirclement through the latter half of July under command of 16th Army, suffering heavy casualties, before its remnants were able to withdraw across the Dniepr River in the first days of August. These came under 20th Army briefly before the 158th was disbanded by August 15.

The second division of this number was designated in January 1942 from the 5th Moscow Workers Rifle Division, which had been defending the Soviet capital since the previous November. After a brief period of reorganization it was assigned to the 22nd Army of Kalinin Front deep inside the Toropets salient.

1st Formation

The division first began forming on September 15, 1939, at Yeysk in the North Caucasus Military District, based on a cadre from the 38th Rifle Division. Its order of battle on June 22, 1941, was as follows:

- 875th Rifle Regiment

- 879th Rifle Regiment

- 881st Rifle Regiment

- 423rd Artillery Regiment

- 535th Howitzer Artillery Regiment[1]

- 196th Antitank Battalion

- 167th Antiaircraft Battalion

- 110th Reconnaissance Battalion

- 274th Sapper Battalion

- 284th Signal Battalion

- 84th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 119th Motor Transport Battalion

Col. Vitalii Ivanovich Novozhilov was appointed to command on the day the division began forming. Since October 1937 he had led several regiments of the 77th Mountain Rifle Division, an ethnic Azerbaijani unit. From October 1940 until May 1941 he was furthering his military education at the Frunze Academy, and his deputy commander (since March 1940), Col. Vasilii Petrovich Brynzov, served as acting commander. This officer had been arrested in August 1938 during the Great Purge, but was released in December 1939 and placed at the disposal of Far Eastern Front. When Novozhilov returned, Brynzov went back to his deputy command.

Battle of Smolensk

In June 1941 the 158th was en route to Ukraine as part of the 34th Rifle Corps of 19th Army in the Reserve of the Supreme High Command. The Corps also contained the 129th and 171st Rifle Divisions.[2] On the day of the German invasion the division was located in the areas of Cherkasy and Bila Tserkva.[3] 19th Army was under command of Lt. Gen. I. S. Konev, and was soon redirected toward the Vitebsk area, where it arrived in piecemeal fashion over several days. In a lengthy after-action report prepared on July 24 by Konev's chief of staff, Maj. Gen. P. N. Rubtsov, the circumstances of this arrival were described in part:

1. Forces of 25th Rifle Corps were mobilized at the moment they took the field. 34th Rifle Corps forces were only in a state of reinforced combat readiness. The divisions were brought up to only 12,000 men, but were not fully mobilized.

In the field the 12,000-man divisions experienced immense difficulties because of an absence of transport and were unable to maneuver. They could not pick up up required quantities of ammunition, could not carry mortars, etc.

2. The artillery arrived late because [it] had arrived in the Kiev region in the first trains and were the first to occupy firing positions in the former deployment region...

Rubtsov went on to note deficiencies in command and control, especially in the use of radio; lack of rear services and reserves; and insufficient reconnaissance.[4] All these would be reflected in the coming battle.

The 171st was transferred to Southwestern Front, and was replaced in the Corps' order of battle by the 38th Division. The 158th officially entered the fighting forces on July 2, when 19th Army became part of Western Front.[5] In a report to the STAVKA late on July 13, the Front commander, Marshal S. K. Timoshenko, stated that he had designated a line behind the Dniepr and Sot Rivers in the Yartsevo and Smolensk regions as the concentration area for the 34th Corps and the 127th Rifle Division "to avoid feeding 19th Army's concentrating forces into combat in piecemeal fashion."[6] However, on July 25 Colonel Brynzov would report that in fact the division had been deployed in such a fashion, leading to disruption and heavy casualties.

Timoshenko reported on the situation east of Vitebsk on the afternoon of July 16, stating in part that 19th Army had regrouped to prepare to retake that place, and that one rifle regiment and one battalion of the 158th was at Novoselki, with the position of the rest of the division being unknown. By now 19th Army was severely disrupted and would soon be disbanded.[7]

Encirclement west of Smolensk

The XXXXVII Panzer Corps, consisting of 29th Motorized Division in the lead, followed by 18th Panzer Division (17th Panzer Division was keeping 20th Army tied down at Orsha), had begun advancing from Horki early on July 13. The left wing rifle divisions of that Army were shoved aside and by dusk the town of Krasnyi, 56km southwest of Smolensk, was in German hands. 16th Army was tasked with the defense of the south approaches to the city, but had only two rifle divisions (46th and 152nd) and the 57th Tank Division under command. Despite serious resistance the 29th Motorized reached the southern outskirts of Smolensk on the evening of July 15; a three-day battle for the city center began the next morning with the 152nd and the 129th Division, which was now under 16th Army. Meanwhile, 17th Panzer was clearing Orsha and pushing 20th Army into an elongated pocket north of the Dniepr west of Smolensk by July 15. In addition, the pocket contained the 129th and 158th, three divisions of 25th Corps, remnants of 5th and 7th Mechanized Corps, and various other formations totalling 20 divisions of several types and states of repair. However, XXXXVII Panzer was extended over 112km and 18th Panzer, as an example, was attempting to take up blocking positions at Krasnyi with just 12 tanks still operating.[8]

By July 17 Timoshenko had been moved up to the position of commander-in-chief of Western Direction and issued new orders to his armies which condemned the "evacuation mood" he sensed among commanders who wished to surrender Smolensk. He insisted that control of the city be regained "at all cost", with specific reference to Lt. Gen. M. F. Lukin's 16th Army, which would soon have the 158th under direct command. The panzer forces continued the compress the pocket, but lacked sufficient motorized infantry to truly seal it off. In addition, Lukin was removing his forces from the western and southwestern sectors in order to concentrate them for the retaking of Smolensk, and generally redeploying to counter German moves; the 158th was generally found in the east and southeast of the pocket. Elements of the division were assigned to the 129th Rifle Divisional Group on July 18 to take part in an attack into the city's southeastern outskirts, but this made hardly a dent in the defenses of 29th Motorized.[9] Colonel Novozhilov had distinguished himself in defending against German armor near the village of Shiryaevo and would win the Order of the Red Banner in August. He would not receive this for some time, because on July 19 he was severely concussed by shellfire and left on the battlefield. Colonel Brynzov took over command of the division until its disbandment. Novozhilov recovered to find himself behind German lines, and by August 20 he was fighting as the deputy commander of the Pervomaisk partisan detachment near Roslavl. He was able to cross the lines on February 5, 1942, and went on to command the 237th Rifle Division.

Heavy fighting around Smolensk, Krasnyi and the perimeter of the pocket continued through July 23. Lukin reported at 0145 hours on July 21 that a further attack by the 158th and 127th Divisions against the southeastern outskirts had failed "because it was organized too late." He also stated that personnel losses had reached 40 percent. Despite the ongoing German pressure to close the pocket a group of forces under Maj. Gen. K. K. Rokossovskii, which included the late-arriving 38th Division, was holding a gap open near Yartsevo permitting limited resupply and an escape route. On July 22 the 158th and 127th renewed their attack and, although ultimately futile, it struck 29th Motorized hard enough to force the diversion of 17th Panzer to stabilize the situation over the next two days, preventing it from closing the Yartsevo gap. It was reported by Western Front that the 158th had only 100 men to contribute to this attack, without any machine guns. Early on July 24 Lukin reported that the two divisions had a total of about 500 men remaining, were reorganizing near Hill 315 and Lozyn, and were awaiting the arrival of a motorized regiment promised by Rokossovskii.[10]

Withdrawal from the pocket

Timoshenko had issued an order on July 21 aimed at reorganizing the forces under his command. 13th Army was reforming prior to attacking to recapture Propoisk and Krychaw and its 35th Rifle Corps was to assemble and reform the 158th, 127th and 50th Rifle Divisions once the pocket was broken. In the event this proved impossible. Instead, during the last week of July the pocket continued to shrink as German infantry releived the panzer forces. Late on July 28 Timoshenko issued what amounted to a personal appeal to his troops as his counteroffensive efforts ran out of steam. 16th Army was specifically directed to attack the newly-arrived 137th Infantry Division. He also urged the STAVKA to, among other actions, provide personnel and weapons to refit the 158th, 127th and 38th Divisions. It was becoming clear that if any part of 16th and 20th Armies were to survive, a breakout would be necessary. Since July 1, 16th Army had suffered over 34,000 casualties. In a further report by Lukin in the afternoon of July 29, 34th Corps was stated as being along the Mokhraia Bogdanovka and Oblogino front, from 6km east to 15km southeast of Smolensk. Elsewhere, Lukin had stated that his forces were no longer in the city, which Timoshenko took to mean that both it and the pocket were being deliberately abandoned, although the increasing pressure from German infantry was leaving no other option. Timoshenko refused to agree and forbade any withdrawal. Lukin replied on July 31, stating his difficulties in coordinating 34th Corps' operations with those of 20th Army, among other issues. Meanwhile, Timoshenko was hedging his bets with the STAVKA by laying the basis for withdrawal.[11]

By this time the pocket measured roughly 20km east to west and 28km north to south. 16th Army's five tattered divisions, including the 158th, were deployed on its southern sector. Fewer than 100,000 Soviet troops remained, and they were nearly out of fuel and ammunition. Lukin stated on August 1 that German forces had penetrated the boundary between the 152nd Division and 34th Corps before reconnoitering toward Dukhovskaya, 15km east of Smolensk. At 1700 hours the 158th was defending Siniavino Station, Hill 215.2, and Mitino front, after being forced aside by the German penetration. At the same it was fighting to prevent a further penetration between it and the 127th Division. Meanwhile, Rokossovskii's group made attempt after attempt to widen the gap into the pocket by forcing back the 7th Panzer Division. Under the circumstances, Timoshenko's only rational course was to save what he could. Late in the day the STAVKA and Western Front tacitly authorized a breakout, although it was refered to as an "attack" toward Dukhovshchina. At 0900 on August 2 Lukin directed 34th Corps to:

defend the Tiushino, Popova, Zaluzh'e, and Vernebisovo sector with strong security detachments in the Sobshino and Malinovka sector on the western bank of the Dnepr River, 30 kilometers east to 35 kilometers east-southeast of Smolensk, to prevent the enemy from penetrating toward the east and northeast and reliably protect the crossings over the Dnepr River...

He also instructed all commanders that they were "personally responsible to the Motherland and government for taking all of your weapons with you during the withdrawal..." This was to begin on the night of August 2/3 against strongpoints held by elements of 20th Motorized Division.[12]

A gap some 10km wide extended between 20th Motorised and 17th Panzer, including several crossing sites over the Dniepr in the Ratchino area. 16th Army moved toward this, with the 158th well to the southwest. The escape attempt continued through August 6. At 2000 hours on August 3 Western Front reported that 34th Corps was "moving from Morevo to the Dnepr River crossing at Ratchino and further south." The withdrawing forces began to run a virtual gauntlet through the gap, often under artillery and air strikes, fording the river in places where it was less than 60cm deep. The operation was largely finished by daybreak on August 5, while a detachment of the division remained east of the Dniepr to provide a rearguard and assist with the crossing of equipment. What remained of 16th Army assembled in the area of Kucherovo, Balakirevo and Tiushino. Lukin reported on the same evening that his divisions were in tatters, moving in various directions after the crossings, and were still engaged in fighting with small German groups; he requested several days for reorganization. However, beginning at 2240 the escaped forces began to be incorporated into the main defensive line. 34th Corps was to relieve two regiments of the 107th Rifle Division some 5-10km southwest of Dorogobuzh by the evening of August 6 while also securing part of the south bank of the Dniepr.[13]

The STAVKA shuffled its leadership within the Front on the same day with Luking moved to command 20th Army; he was promised that the remnants of his 16th Army would be incorporated into the 20th before being moved to the rear to reconstituted as the 16th. The next day the 158th officially came under 20th Army. The division was noted as being at Vygor and Kaskovo, between 26km and 28km southeast of Solovevo. While there is little agreement on numbers, it seems that as many as 50,000 soldiers of the two Armies managed to escape from the sack. However, the individual divisions had been weakened to 1,000 - 2,000 personnel on average and were considerably weaker in infantry. The 158th had fared even worse than most, and under Army Order No. 0014 of August 8 the 34th Corps was to be disbanded along with the division, with the remaining men and equipment encorporated into the 127th Division. The 158th ceased to exist on August 15, and three days later Colonel Brynzov took command of the 106th Motorized Division.[14][15] He was wounded and hospitalized on August 28 and never held another field command, although he gained the rank of major general on October 29, 1943. He spent long stays in hospital in 1943 and 1946 before finally being retired on May 4, 1948, although he lived until June 3, 1962.

2nd Formation

A new 158th was formed from January 15-20, 1942, in the Moscow Defence Zone, based on the 5th Moscow Workers Rifle Division.[16][17] (NOTE: Not to be confused with the 5th Moscow Rifle Division of National Opolchenie (Frunze District))

5th Moscow Workers Rifle Division

The Moscow Fighter (Destruction) Battalions began forming under the NKVD in early July 1941 and by July 12 some 25 had been enlisted. The battalions of 13 city districts were consolidated into three regiments, and on October 17 these came under the 3rd Combat Section under command of NKVD Col. Stepan Efimovich Isaev. This officer had been trained by the Frunze Academy in the previous year and had raised the battalion of the Leningradskii District in July. The three regiments were consolidated into the 2nd Moscow Defense Brigade on October 28, and this in turn was reorganized on November 14 as the 5th Moscow Workers Rifle Division with the following order of battle:

- 7th (Militia) Rifle Regiment

- 8th (Militia) Rifle Regiment

- 9th (Militia) Rifle Regiment[18]

- Unnumbered Artillery Regiment, Antitank Battalion, Antiaircraft Battery, Mortar Battalion, Reconnaissance Company, Sapper Battalion, Signal Battalion, Medical/Sanitation Battalion, Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Platoon, Auto Transport Company, Divisional Veterinary Hospital

At this time the division had 7,291 personnel, 4,200 of whom were members of the Communist Party or Komsomols.[19] Colonel Isaev remained in command.

Battle of Moscow

Already on October 17-18 the Brigade, along with those units that would later become the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Moscow Workers Divisions, had been moved outside the city to take up and build positions in the suburbs. Between them they covered the main routes leading to Moscow from the west, specifically the Kyiv and Minsk highways plus the Kaluga, Volokolamsk, Leningrad, and Dmitrov roads. In addition the militiamen carried out reconnissance on the front lines and combat with German forces that had become bogged down in the late stages of Operation Typhoon.[20]

At the start of December the Moscow Defense Zone was defending the capital with 24th and 60th Armies in the outer defensive belt; the main defensive zone was held by the 3rd, 4th, and 5th Workers Divisions, 332nd Rifle Division, nine artillery regiments, eight artillery battalions, five machine gun battalions, seven flamethrower companies, and three companies of anti-tank dogs. There were also two rifle divisions and several other formations in reserve. Altogether this amounted to about 200,000 men.[21] 5th Moscow was now considered ready for combat, with 11,700 personnel on strength; however, they were armed with only 6,961 rifles, two submachine guns, 271 light and heavy machine guns, and 29 artillery pieces of various calibres. On December 5 the Soviet armies began to go over to the counteroffensive, and the following day the division was officially transferred to Red Army control.[22] As of January 1, 1942, the 5th Moscow Workers was still in the Moscow Defense Zone[23] as the forces of Western Front surged ahead. From January 15-20 the division was reorganized as the new 158th Rifle Division, with the following order of battle:

- 875th Rifle Regiment

- 879th Rifle Regiment (until March 14, 1945)

- 881st Rifle Regiment

- 599th Rifle Regiment (from April 19, 1945)

- 423rd Artillery Regiment[24]

- 323rd Antitank Battalion (later 273rd)

- 455th Antiaircraft Battery (until May 10, 1943)

- 803rd Mortar Battalion (until October 9, 1942)

- 471st Machine Gun Battalion (from January 10, 1942 until May 1, 1943)

- 110th Reconnaissance Company

- 274th Sapper Battalion

- 284th Signal Battalion (later 591st, 1445th Signal Companies)

- 84th Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 179th Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Platoon

- 260th Motor Transport Company

- 137th Field Bakery

- 996th Divisional Veterinary Hospital

- 73741st Field Postal Station (later 1804th, 1508th)

- 1603rd Field Office of the State Bank (later 1133rd)

Colonel Isaev remained in command of the division. Under a STAVKA order of January 19 it was to transferred, along with the 155th Rifle Division, via Ostashkov, to the 4th Shock Army in Kalinin Front.[25] However, on February 22 the 158th was reassigned to 22nd Army in the same Front.[26] During the Toropets–Kholm offensive (January 9 - February 6) this Front had deeply outflanked German 9th Army and nearly encircled it from the west, creating the Rzhev salient. Isaev was removed from his post on February 27 and was soon given command of the 234th Rifle Regiment of 179th Rifle Division. On March 7 Maj. Gen. Aleksei Ivanovich Zygin took over the 158th. This officer had previously led the 174th and 186th Rifle Divisions.

Battles for Rzhev

The second phase of the Rzhev-Vyazma operation had begun at the start of February, when German forces launched counterstrokes in all the main directions of the Soviet operations. The Soviet armies were significantly weakened from casualties and were mostly operating on very tenuous supply lines. All efforts to liberate Vyazma had failed. On February 5, most of Kalinin Front's 29th Army was cut off from 39th Army and encircled. After several attempts to rejoin with the 39th, by mid-month it was decided to regroup to join hands with 22nd Army. By the end of February only 5,200 personnel had managed to escape. Meanwhile, the 22nd was attempting to finally seize Bely as a preliminary to eliminating the German Olenino grouping, but this was unsuccessful.[27]

On March 20 the STAVKA again demanded that Kalinin Front finish off the Olenino grouping with the 22nd, 39th, and 30th Armies. This made no progress due to the general exhaustion of the troops. For example, 22nd Army had, in terms of numbers, since the start of the counteroffensive in January had lost its entire complement twice over. Replacements were largely untrained and ammunition was in short supply. In addition, the spring rasputitsa was about to begin.[28] By April 1 the 158th had come under direct command of the Front, and during that month it was transferred to 30th Army.[29] General Zygin left the division on May 18, moving to command of 58th Army about a month later, and would subsequently lead three other armies, including the 39th during Operation Mars, before being killed in action on September 27, 1943. Col. Mikhail Mikhailovich Busarov took over command; this NKVD officer had been serving on the staff of 30th Army and would be promoted to the rank of major general on January 27, 1943.

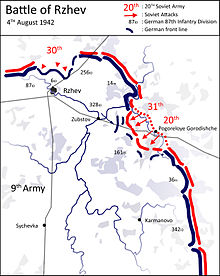

The 158th was still in 30th Army during the First Rzhev–Sychyovka Offensive Operation. On August 5 the STAVKA placed Army Gen. G. K. Zhukov in overall command of the operation, which had begun several days earlier. Zhukov proposed to take Rzhev as soon as August 9 through a double envelopment by 30th and 31st Armies. In the event there were no real successes on this sector of the front until August 20, when elements of 30th Army finally cleared the village of Polunino and closed on the eastern outskirts of Rzhev. Over the following days further efforts were made to break into the town, but these were unsuccessful.[30] By the beginning of September the 158th had been moved to 39th Army when 30th Army was reassigned to Western Front.[31]

Operation Mars

General Zygin was in command of 39th Army in November; the Army was deployed at the northernmost tip of the Rzhev salient, around the village of Molodoi Tud and the small river of the same name. In the planning for Operation Mars the main weight of the attack was to come from Western Front's 20th Army and Kalinin Front's 41st Army to pinch off the main body of 9th Army north of Sychyovka. 39th Army's task was largely diversionary in nature, intended to draw German reserves, but if successful it would reach and cut the Rzhev–Olenino road and railroad.[32]

References

Citations

- ^ Charles C. Sharp, "Red Legions", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed Before June 1941, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. VIII, Nafziger, 1996, p. 79

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 10

- ^ Sharp, "Red Legions", p. 79

- ^ David M. Glantz, Stumbling Colossus, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1998, pp. 208-09

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1941, p. 23

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2010, Kindle ed., ch. 3

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., ch. 6. The regiment is numbered as the 720th in this source; this regiment was in 162nd Rifle Division, also part of 19th Army.

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., ch. 3

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., ch. 4

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., ch. 4

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., ch. 5

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., ch. 7

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., ch. 7

- ^ Glantz, Barbarossa Derailed, Vol. 1, Kindle ed., chs. 7, 9

- ^ Walter S. Dunn Jr., Stalin's Keys to Victory, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2007, p. 65

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed From 1942 to 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. X, Nafziger, 1996, p. 63

- ^ Dunn Jr., Stalin's Keys to Victory, p. 74

- ^ Sharp, "Red Volunteers", Soviet Militia Units, Rifle and Ski Brigades 1941 - 1945 Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. XI, Nafziger, 1996, p. 115

- ^ Sharp, "Red Volunteers", p. 115

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2015, Kindle ed., Part III, ch. 8

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Moscow, Kindle ed., Part III, ch. 8

- ^ Sharp, "Red Volunteers", p. 115

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, p. 14

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", Soviet Rifle Divisions Formed From 1942 to 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. X, Nafziger, 1996, p. 63

- ^ Svetlana Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, ed. & trans. S. Britton, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2013, p. 188

- ^ Sharp, "Red Swarm", p. 63

- ^ Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, pp. 38-39, 43

- ^ Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, p. 45

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, pp. 63, 82

- ^ Gerasimova, The Rzhev Slaughterhouse, pp. 83, 86-87

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1942, pp. 166, 168

- ^ Glantz, Zhukov's Greatest Defeat, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 1999, pp. 28-30

Bibliography

- Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. pp. 77, 210

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. pp. 179-80