Utulei, American Samoa

Utulei | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| Coordinates: 14°17′13″S 170°40′59″W / 14.28694°S 170.68306°W | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| County | Maoputasi |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.33 sq mi (0.85 km2) |

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 479 |

| • Density | 1,500/sq mi (560/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−11 (Samoa Time Zone) |

| ZIP code | 96799 |

| Area code | +1 684 |

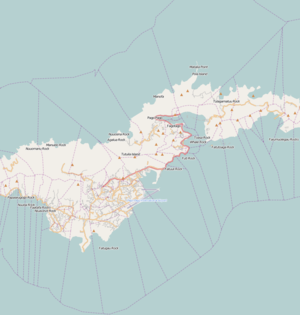

Utulei or ʻUtulei is a village in Maoputasi County, in the Eastern District of Tutuila, the main island of American Samoa. Utulei is traditionally considered to be a section of Fagatogo village, the legislative capital of American Samoa, and is located on the southwest edge of Pago Pago Harbor.[1][2][3] Utulei is the site of many local landmarks: The A. P. Lutali Executive Office Building, which is next to the Feleti Barstow Library; paved roads that wind up to a former cablecar terminal on Solo Hill; the governor's mansion, which sits on Mauga o Alii, overlooking the entrance to Goat's Island, and the lieutenant governor's residence directly downhill from it; the Lee Auditorium, built in 1962; American Samoa's television studios, known as the Michael J. Kirwan Educational Television Center; and the Rainmaker Hotel (a portion of which is now known as Sadie's Hotel). Utulei Terminal offers views of Rainmaker Mountain.[4]

Also in Utulei are some of the hotels based in Pago Pago, such as Sadie’s by the Sea,[5] and the Feleti Barstow Library (American Samoa’s central public library), which is located across from Samoana High School.[6][7][8] The library, which has the largest selection of literature in American Samoa,[9] was developed between 1998 and 2000 with funds from the Community Development Block Grant, a program of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.[citation needed]

Utulei Beach Park has an enormous fale with ornate carvings, which is used for performances and events. Smaller fales in the park are used for everyday gatherings. Across from Utulei Beach Park is the Executive Office Building and Feleti Barstow Public Library. Next to the library is the largest high school on Tutuila Island, Samoana High School.[10]

History

| Year | Population[11] |

|---|---|

| 2020 | 479 |

| 2010 | 684 |

| 2000 | 807 |

| 1990 | 930 |

| 1980 | 980 |

| 1970 | 1,074 |

| 1960 | 719 |

| 1950 | 744 |

| 1940 | 488 |

| 1930 | 375 |

Utulei is by tradition considered distinct from Fagatogo because it is the site of Maota o Tanumaleu, the residence of the High Chief Afoafouvale (also known as the Le Aloalii). The current holder of that title is Afoa Moega Lutu, who has held it since 1990.

On November 3, 1920, Governor Warren Terhune mounted to the second floor of the Government House in Utulei, entered a room commanding an unobstructed view to the south through the entrance of Pago Pago Bay, and committed suicide by shooting himself.[12][13]

During World War II, the population of the village of Utulei, around 700 inhabitants, was almost entirely displaced to make room for US military installations. One Naval officer was said to have describe Utulei as consisting of "a few native houses". The inhabitants were told to move out of the village and into the hills, and bachelor officers’ quarters and other military support facilities were built there.[14] During World War II, the 1922 facilities for the storage of oil were insufficient for the demands of the war, and had to be replaced by a new oil dock in Fagatogo and a new tank farm at Utulei, the two being connected by piping. The electric power plant, which had lighted the U.S. Naval Station, gave way to two larger plants located respectively in Pago Pago and in Utulei, which provided power for the ship repair unit and other vital wartime installations.[15]

On January 11, 1942, during World War II, shells from a Japanese submarine struck, ironically enough, the house of one of the few Japanese residents, Mr. Frank Shimasake, in Utulei, the only Japanese-owned building in the archipelago.[16][17]

In 1946, a vocational school was established in the former Marine barracks at Utulei, under the direction of Harry Matsinger, an educator from Hawai’i. Twelve of its fourteen teachers were perforce Americans, and their salaries alone amounted to roughly one-fifth of the total educational budget in American Samoa.[18]

In 1946, the Public Health Department of American Samoa found its facilities grossly inadequate for the post-war demand. The old hospital, built in 1914, was too small and antiquated, and the U.S. Navy’s Medical Department could not be expected to provide all health services indefinitely. To address this issue, Governor Harold Houser turned two-story barracks at Utulei over to the department. These now-vacant Marine barracks were renovated and repurposed as a new 224-bed hospital—sometimes referred to as the Hospital of American Samoa — and included between 24 and 27 bassinets, along with a pharmacy and a dentistry. The hospital opened its doors in 1946. By 1950, it had admitted 2,771 patients and delivered around 40 percent of all babies born that year in American Samoa. Nursing needs were met by graduates of the local nursing school, while medical requirements were fulfilled by students chosen for the Central Medical School.[19][20]: 247 and 267 After the Navy's departure in 1951, however, there was a severe shortage of physicians and other health care professionals. In 1954, for example, there were only four doctors (one stateside and three European), and only one dentist. The hospital therefore depended heavily on nurses to provide its patient care.[20]: 268

In 1964, the Michael J. Kirwan Educational Television Center was completed.[21] It is named for Representative Michael J. Kirwan, who was chairman of the House Appropriations Committee.[20]: 279–280 [22]

In the late 1960s, questions about where American Sāmoa's capital should be arose again after Governor Owen Aspinall moved his office to Utulei. Some argued that this violated the American Sāmoa Constitution, which designates Fagatogo as the capital and seat of government. Aspinall, however, was protected by the fact that Utulei is a subvillage of Fagatogo.[23]

In 1980, during celebratory Flag Day military demonstrations, a U.S. Navy airplane accidentally hit the cables of the Mount ‘Alava Cable Car and crashed into the Rainmaker Hotel. All six naval personnel on board the aircraft died, as did two hotel guests.[24]: 167

In 1995, Governor A. P. Lutali restructured the Public Library Board to implement the 1989 plan for establishing a main public library in American Sāmoa. Construction of the library in Utulei was completed in 1998, resulting in an 11,000-square-foot facility built by Fletcher Construction, a New Zealand-based firm. After 18 months of legislation, development, and planning, Cheryl Ann Morales and her team officially opened the library to the public on April 15, 2000. The library quickly became a central hub for community activities in Utulei.[25]

Geography

Surface runoff - from Utulei Ridge, the Togotogo Ridge, and Matai Mountain - flows through Utulei, carried by the Vailoa Stream. The stream discharges into the sea at a point on the north side of the Pago Pago Yacht Club in Utulei.[26]: 24–26

Historical records reveal that, prior to 1900, extensive areas along the Pago Pago Harbor coastline, including the present-day locations of Aua and Utulei villages, were covered by mangrove vegetation.[27]

Utulei Beach Park

Utulei Beach Park is one of only a few public parks in Pago Pago — and on Tutuila Island as a whole. It was built by the U.S. Navy in the 1940s by filling in a marshy area near the Pago Pago Harbor. Next to the park are two historic naval buildings erected in the 1940s — two of four remaining original structures built here by the Navy during World War II - as well as the Pago Pago Yacht Club and the ASG Tourism Office. The park includes a grassy area with scattered trees and picnic sites. It is used for recreational activities, such as volleyball and picnicking, and is a common gathering place for social activities and events. The adjoining beach is used for canoe racing, kayaking, and windsurfing.[28]

In 2006, the governor proposed approving the addition of a McDonald's restaurant to Utulei Beach. He said he hoped the restaurant would boost activity during the evenings, a time when the area was usually almost deserted. This was a controversial proposal, because Utulei Beach is a designated park area that has received substantial funding from the National Park Service.[29] The proposal was defeated.

In 2009,then-Governor Togiola Tulafono designated Su’igaula o le Atuvasa as one of the venues for the 10th Festival of Pacific Arts, slated to be hosted by American Samoa in the summer of 2010. Su’igaula o le Atuvasa is the portion of the beach closest to the former site of the Pago Pago Yacht Club.[30]

Another public park in Utulei is Su’igaulaoleatuvasa, which is managed by the American Samoa Parks and Recreation department.[31]

Tourism

The $10-million A. P. Lutali Executive Office Building, constructed in 1991, is located near the Pago Pago Yacht Club. The Feleti Barstow Public Library, constructed in 1998, is located just behind the Executive Office Building. Beyond the library is a paved road that winds upwards to the former cable-car terminal on Solo Hill. A monument on the hill recalls a 1980 disaster in which a U.S. Navy airplane hit the cables and crashed into the Rainmaker Hotel, killing eight people. The cableway had been one of the world's longest single-span aerial tramways; it had been constructed in 1965 to carry TV technicians to the transmitters at the top of Mount ʻAlava. In December 1991, Hurricane Val put the cableway out of service, and it has yet to be repaired. But the Utulei terminal is still visited because of its views, including its view of Mt. Pioa (also called the Rainmaker Mountain.

Also located in Utulei are the Lee Auditorium, built in 1962, and the Michael J. Kirwan Educational Television Center.[32][24]: 166 It was at this television center, during the tenure of Governor H. Rex Lee, that the pioneering practice began of broadcasting school lessons to elementary and secondary school students Guided tours of the Michael J. Kirwan TV Studios have been available in the past.[24]: 167

The two-story Governor's House is a wooden colonial mansion atop Mauga o Ali'i (the chief's hill), uphill from a road across which is the entrance to the Rainmaker Hotel. The mansion was constructed in 1903, and served as the residence of each of the island’s naval commanders in turn until 1951. At that point, the Department of the Interior assumed control of the mansion, and it has been the residence of every governor of American Samoa since then.[24]: 167

Pago Pago Yacht Club, next to the Canoe Club in Utulei, is the center of water sports activities in American Samoa. It offers game fishing, diving, canoeing, sailing, diving, and more. The historic club building, next to Pago Pago Harbor, is used as a place to retreat and for dining. The yacht club is a member of the International Yacht Racing Union and the American Samoa National Olympic Committee.[33]

Utulei is also home to Tauese PF Sunia Ocean Center, which is the visitor center for the National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa. It offers informative exhibits on region's ecosystems and reefs.[34][35]

Blunt's Point

Blunt's Point, on Matautu Ridge in Gataivai, overlooks the mouth of Pago Pago Harbor. On it are two large six-inch naval guns that were emplaced in 1941. Matautu Ridge can be reached from Utulei by walking southeast on the main road past the oil tanks, keeping an eye out on the right-hand side for a small pump house immediately across the highway from a beach, and almost opposite two homes on the bayside of the street. The track up the hill to Matautu Ridge starts behind the pump house. The lower gun is located directly over a big green water tank, and the second gun is located 200 meters farther up the Matautu Ridge. Concrete stairways lead to both of the guns.[32] One gun emplacement is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places, while the second gun has earned recognition as a U.S. National Historic Landmark. They are maintained by the National Park Service.[36] The 3-km World War II Heritage Trail, which ends at Blunt's Point, is the most accessible and most popular trail on Tutuila Island. The ridge-top trail winds past various ancient archeological sites as well as World War II installations that were erected to fend off a potential Japanese invasion.[37] Farther on, the trail leads into a bird-filled rainforest.[38]

Landmarks

- Utulei Beach Park (Su'iga'ula le Atuvasa Beach Park)

- Blunts Point Battery, National Historic Landmark on Matautu Ridge

- Governor H. Rex Lee Auditorium ("Turtle House"), listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Michael J. Kirwan Educational Television Center, listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Rainmaker Hotel, former luxury hotel

- Tauese PF Sunia Ocean Center, visitor center for the National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa

- Government House

Economy

At the time of the 1990 U.S. Census, there were 156 houses in Utulei village. Between 1990 and 1995, 23 new residential building permits were issued, so that, by 1995, there were 179 houses. As of 2000, there were 60 commercial enterprises registered in the village, many of which are housed in the one- or two-story buildings on the southwest side of the shoreline roadway. Smaller shops are found in predominantly residential communities upland from Samoana High School and the Executive Office Building.[26]: 24-23 and 24-25

Diesel fuel is delivered monthly to Tutuila Island from Long Beach, California, and Honolulu, Hawaii, supplied by Marlex and Pacific Resources, Inc. The fuel is carried by pipe from the dock area to an energy-storage tank farm operated by Marlex in the Punaoa Valley in Utulei.[39]

Education

The American Samoa Department of Education operates Samoana High School in Utulei (originally called the High School of American Samoa).[40] It opened in 1946, and was the first high school established in the territory.

The American Samoa Community College (ASCC), established in 1970, was located in Utulei during its first four years of operation. From 1972 to 1974, it was housed in the former Fia lloa High School building[41] and in the former navy buildings that had once housed the High School of American Samoa. By the spring of 1972, the college had 872 enrolled students.[42]

Feleti Barstow Public Library, the central public library for American Samoa, is located in Utulei.

Notable people

- Peter Tali Coleman, the first-appointed, first-elected, and longest-serving governor of American Samoa

- Afoa Moega Lutu, politician and lawyer

- Arieta Enesi Mulitauaopele, nurse and first Samoan woman to run in a gubernatorial election, and women’s rights activist.[43]

- Tapumanaia Galu Satele Jr., former member of the American Samoa House of Representatives

- Lealaialoa F. Michael, first chief justice of Samoan descent.[44]

- Aleki Sene, first Director of the American Samoa Telecommunications Authority (ASTCA).[45]

- Caroline Sinavaiana-Gabbard, professor and author

- Solinuu Shimasaki, first female Senator in the American Samoa Senate and chieftess

- Faumuina Tolopa, former senator in the Fono.[46]

- Malouamaua Afele Tuiolosega, Airborne Ranger Paratrooper.[47]

- Robert Filo Niko, missionary.[48]

- Michael Kruse, first Chief Justice of Samoan ancestry.[49]

References

- ^ Margolis, Susanna (1995). Adventuring in the Pacific: Polynesia, Melanesia, Micronesia. Sierra Club Books. Page 195. ISBN 9780871563903.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō I. F. (1998). The Story of the Legislature of American Samoa. Legislature of American Samoa. Page 168. ISBN 9789829008015.

- ^ Google Maps: Utulei, Eastern, American Samoa, accessed 12 March 2018.

- ^ Stanley, David (1999). South Pacific Handbook. David Stanley. Pages 441-443. ISBN 9781566911726.

- ^ Cruise Travel Vol. 2, No. 1 (July 1980). Lakeside Publishing Co. Page 60. ISSN 0199-5111.

- ^ "American samoa". Archived from the original on 2017-10-22. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- ^ Talbot, Dorinda and Deanna Swaney (1998). Samoa. Lonely Planet. Page 158. ISBN 9780864425553.

- ^ Stanley, David (1993). South Pacific Handbook. David Stanley. Page 367. ISBN 9780918373991.

- ^ Goodwin, Bill (2006). Frommer’s South Pacific. Wiley. Page 397. ISBN 9780471769804.

- ^ Clayville, Melinda (2021). Explore American Samoa: The Complete Guide to Tutuila, Aunu'u, and Manu'a Islands. Page 41. ISBN 9798556052970.

- ^ "American Samoa Statistical Yearbook 2016" (PDF). American Samoa Department of Commerce.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 198. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ "SAMOAN GOVERNOR COMMITS SUICIDE; Naval Commander Terhune of Hackensack, N.J., Shoots Himself when Suspended. WAS TO FACE AN INQUIRY Troubles with Natives Led to Charges Against His Administration There". The New York Times. 6 November 1920.

- ^ Kennedy, Joseph (2009). The Tropical Frontier: America’s South Sea Colony. University of Hawai'i Press. Page 201 and 213. ISBN 9780980033151.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 243. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 241. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Kennedy, Joseph (2009). The Tropical Frontier: America's South Sea Colony. University of Hawai'i Press. Page 207. ISBN 9780980033151.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 250. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1960). Amerika Samoa: A History of American Samoa and its United States Naval Administration. United States Naval Institute. Page 251. ISBN 9780870210747.

- ^ a b c Sunia, Fofo I.F. (2009). A History of American Samoa. Amerika Samoa Humanities Council. ISBN 9781573062992.

- ^ "Weekly Highlight 11/13/2009 Michael J. Kirwan Educational Television Center, Tutuila Island, Western, American Samoa".

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Page 61. ISBN 9829036022.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō I. F. (1998). The Story of the Legislature of American Samoa. Legislature of American Samoa. Page 168. ISBN 9789829008015.

- ^ a b c d Swaney, Deanna (1994). Samoa: Western & American Samoa: a Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit. Lonely Planet Publications. ISBN 9780864422255.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Page 97. ISBN 9829036022.

- ^ a b "AMERICAN SAMOA WATERSHED PROTECTION PLAN" (PDF). American Samoa Environmental Protection Agency. January 2000. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (1999). Coastal Management Profiles: A Directory of Pacific Island Governments and Non Government Agencies with Coastal Management Related Responsibilities. SPREP's Climate Change and Integrated Coastal Management Programme. Page 23. ISBN 9789820401983.

- ^ United States National Park Service (1997). National Park of American Samoa, General Management Plan (GP), Islands of Tutuila, Ta'u, and Ofu: Environmental Impact Statement. Page 39.

- ^ "American Samoa Governor backs beachfront McDonalds". 16 May 2006.

- ^ "Half mil budgeted to improve Su'igaula o le Atuvasa Park". Samoa News. 21 July 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Park usage numbers increase despite major problems with vandalism and limited facilities". 25 February 2013.

- ^ a b Stanley, David (2004). Moon Handbooks South Pacific. David Stanley. Page 475. ISBN 9781566914116.

- ^ International Business Publications IBP, Inc. (2007). Samoa (American): Doing Business, Investing in Samoa (American) Guide - Strategic Information, Regulations, Contacts. Lulu Press, Inc. Page 135. ISBN 9781433011863.

- ^ "Tauese PF Sunia Ocean Center | American Samoa Attractions".

- ^ Atkinson, Brett (2016). Lonely Planet Rarotonga, Samoa & Tonga. Lonely Planet Publications. Page 154. ISBN 9781786572172.

- ^ "Blunts Point gun encasements cleaned up". 27 November 2013.

- ^ "American Samoa: Tramping the tropics".

- ^ Lomax, Becky (2018). Moon USA National Parks: The Complete Guide to All 59 Parks. Moon Travel Guides. ISBN 9781640492790.

- ^ "United States of America Insular Areas Energy Assessment Report". Department of Interior. p. 152. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Sutter, Frederic Koehler (1989). The Samoans: A Global Family. University of Hawaii Press. Page 215. ISBN 9780824812386.

- ^ Crocombe, R.G. and Malama Meleisea (1988). Pacific Universities: Achievements, Problems, Prospects. The University of the South Pacific. Page 218. ISBN 9789820200395.

- ^ Sunia, Fofo I.F. (2009). A History of American Samoa. Amerika Samoa Humanities Council. Page 307. ISBN 9781573062992.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Pages 99-100. ISBN 9829036022.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Page 62. ISBN 9829036022.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Pages 128-129. ISBN 9829036022.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō I. F. (1998). The Story of the Legislature of American Samoa. Legislature of American Samoa. Page 257. ISBN 9789829008015.

- ^ Sutter, Frederic Koehler (1989). The Samoans: A Global Family. University of Hawai'i Press. Page 189. ISBN 9780824812386.

- ^ Sutter, Frederic Koehler (1989). The Samoans: A Global Family. University of Hawaiʻi Press. Page 186. ISBN 9780824812386.

- ^ Sunia, Fofō Iosefa Fiti (2001). Puputoa: Host of Heroes - A record of the history makers in the First Century of American Samoa, 1900-2000. Suva, Fiji: Oceania Printers. Page 62. ISBN 9829036022.