Urate oxidase

| UOX | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | UOX, UOXP, URICASE, Urate oxidase, urate oxidase (pseudogene) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | MGI: 98907; GeneCards: UOX; OMA:UOX - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The enzyme urate oxidase (UO), uricase or factor-independent urate hydroxylase, absent in humans, catalyzes the oxidation of uric acid to 5-hydroxyisourate:[4]

- Uric acid + O2 + H2O → 5-hydroxyisourate + H2O2

- 5-hydroxyisourate + H2O → 2-oxo-4-hydroxy-4-carboxy-5-ureidoimidazoline

- 2-oxo-4-hydroxy-4-carboxy-5-ureidoimidazoline → allantoin + CO2

Structure

Urate oxidase is mainly localised in the liver, where it forms a large electron-dense paracrystalline core in many peroxisomes.[5] The enzyme exists as a tetramer of identical subunits, each containing a possible type 2 copper-binding site.[6]

Urate oxidase is a homotetrameric enzyme containing four identical active sites situated at the interfaces between its four subunits. UO from A. flavus is made up of 301 residues and has a molecular weight of 33438 daltons. It is unique among the oxidases in that it does not require a metal atom or an organic co-factor for catalysis. Sequence analysis of several organisms has determined that there are 24 amino acids which are conserved, and of these, 15 are involved with the active site.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reaction mechanism

Urate oxidase is the first enzyme in a pathway of three enzymes to convert uric acid to S-(+)-allantoin. After uric acid is converted to 5-hydroxyisourate by urate oxidase, 5-hydroxyisourate (HIU) is converted to 2-oxo-4-hydroxy-4-carboxy-5-ureidoimidazoline (OHCU) by HIU hydrolase, and then to S-(+)-allantoin by 2-oxo-4-hydroxy-4-carboxy-5-ureidoimidazoline decarboxylase (OHCU decarboxylase). Without HIU hydrolase and OHCU decarboxylase, HIU will spontaneously decompose into racemic allantoin.[7]

The active site binds uric acid (and its analogues), allowing it to interact with O2.[8] According to X-ray crystallography, it is the conjugate base of uric acid that binds and is then deprotonated to a dianion. The dianion is stabilized by extensive hydrogen-bonding, e.g., to Arg 176 and Gln 228 .[9] Oxygen accepts two electrons from the urate dianion, via a sequence of one-electron transfers, ultimately yielding hydrogen peroxide and the dehydrogenated substrate. The dehydrourate adds water (hydrates) to produce 5-hydroxyisourate.[10]

Urate oxidase is known to be inhibited by both cyanide and chloride ions. Inhibition involves anion-π interactions between the inhibitor and the uric acid substrate.[11]

Significance of absence in humans

Urate oxidase is found in nearly all organisms, from bacteria to mammals, but is inactive in humans and all apes (great and lesser apes), having been lost in hominoid ancestors during primate evolution.[6] This means that instead of producing allantoin as the end product of purine oxidation, the pathway ends with uric acid. This leads to humans having much higher and more highly variable levels of urate in the blood than most other mammals.[12]

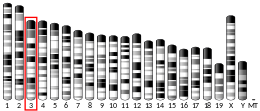

Genetically, the loss of urate oxidase function in humans was caused by two nonsense mutations at codons 33 and 187 and an aberrant splice site.[13]

It has been proposed that the loss of urate oxidase gene expression has been advantageous to hominoids, since uric acid is a powerful antioxidant and scavenger of singlet oxygen and radicals. Its presence provides the body with protection from oxidative damage, thus prolonging life and decreasing age-specific cancer rates.[14]

However, uric acid plays a complex physiological role in several processes, including inflammation and danger signalling,[15] and modern purine-rich diets can lead to hyperuricaemia, which is linked to many diseases including an increased risk of developing gout.[12]

Medical uses

Urate oxidase is formulated as a protein drug (rasburicase) for the treatment of acute hyperuricemia in patients receiving chemotherapy. A PEGylated form of urate oxidase, pegloticase, was FDA approved in 2010 for the treatment of chronic gout in adult patients refractory to "conventional therapy".[16]

Disease relevance

Children with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL), specifically with Burkitt's lymphoma and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), often experience tumor lysis syndrome (TLS), which occurs when breakdown of tumor cells by chemotherapy releases uric acid and cause the formation of uric acid crystals in the renal tubules and collecting ducts. This can lead to kidney failure and even death. Studies suggest that patients at a high risk of developing TLS may benefit from the administration of urate oxidase.[17] However, humans lack the subsequent enzyme HIU hydroxylase in the pathway to degrade uric acid to allantoin, so long-term urate oxidase therapy could potentially have harmful effects because of toxic effects of HIU.[18]

Higher uric acid levels have also been associated with epilepsy. However, it was found in mouse models that disrupting urate oxidase actually decreases brain excitability and susceptibility to seizures.[19]

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is often a side effect of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT), driven by donor T cells destroying host tissue. Uric acid has been shown to increase T cell response, so clinical trials have shown that urate oxidase can be administered to decrease uric acid levels in the patient and subsequently decrease the likelihood of GVHD.[20]

In legumes

UO is also an essential enzyme in the ureide pathway, where nitrogen fixation occurs in the root nodules of legumes. The fixed nitrogen is converted to metabolites that are transported from the roots throughout the plant to provide the needed nitrogen for amino acid biosynthesis.

In legumes, 2 forms of uricase are found: in the roots, the tetrameric form; and, in the uninfected cells of root nodules, a monomeric form, which plays an important role in nitrogen-fixation.[21]

Convergent evolution

Urate oxidase is a notable example of the existence of non-homologous isofunctional enzymes, proteins with independent evolutionary origin catalyzing the same chemical reaction.

Besides the cofactorless urate oxidase (UOX), which is found in all three domains of life, other bacterial proteins are known that catalyze the same reaction without being evolutionarily related to UOX. These are two different oxidases (named HpxO and HpyO) that use FAD and NAD+ as cofactors, and one integral membrane protein (named PuuD) that additionally contains a cytochrome c protein domain.[22]

See also

References

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000028186 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Motojima K, Kanaya S, Goto S (November 1988). "Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for rat liver uricase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 263 (32): 16677–81. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)37443-X. PMID 3182808.

- ^ Motojima K, Goto S (May 1990). "Organization of rat uricase chromosomal gene differs greatly from that of the corresponding plant gene". FEBS Letters. 264 (1): 156–8. Bibcode:1990FEBSL.264..156M. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(90)80789-L. PMID 2338140. S2CID 36132942.

- ^ a b Wu XW, Lee CC, Muzny DM, Caskey CT (December 1989). "Urate oxidase: primary structure and evolutionary implications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 86 (23): 9412–6. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.9412W. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.23.9412. PMC 298506. PMID 2594778.

- ^ Ramazzina I, Folli C, Secchi A, Berni R, Percudani R (March 2006). "Completing the uric acid degradation pathway through phylogenetic comparison of whole genomes". Nature Chemical Biology. 2 (3): 144–8. doi:10.1038/nchembio768. PMID 16462750. S2CID 13441301.

- ^ Gabison L, Prangé T, Colloc'h N, El Hajji M, Castro B, Chiadmi M (July 2008). "Structural analysis of urate oxidase in complex with its natural substrate inhibited by cyanide: mechanistic implications". BMC Structural Biology. 8: 32. doi:10.1186/1472-6807-8-32. PMC 2490695. PMID 18638417.

- ^ Colloc'h N, el Hajji M, Bachet B, L'Hermite G, Schiltz M, Prangé T, Castro B, Mornon JP (November 1997). "Crystal structure of the protein drug urate oxidase-inhibitor complex at 2.05 A resolution". Nature Structural Biology. 4 (11): 947–52. doi:10.1038/nsb1197-947. PMID 9360612. S2CID 1282767.

- ^ Oksanen E, Blakeley MP, El-Hajji M, Ryde U, Budayova-Spano M (2014-01-23). "The Neutron Structure of Urate Oxidase Resolves a Long-Standing Mechanistic Conundrum and Reveals Unexpected Changes in Protonation". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e86651. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...986651O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086651. PMC 3900588. PMID 24466188.

- ^ Estarellas C, Frontera A, Quiñonero D, Deyà PM (January 2011). "Relevant anion-π interactions in biological systems: the case of urate oxidase". Angewandte Chemie. 50 (2): 415–8. doi:10.1002/anie.201005635. PMID 21132687.

- ^ a b So A, Thorens B (June 2010). "Uric acid transport and disease". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 120 (6): 1791–9. doi:10.1172/JCI42344. PMC 2877959. PMID 20516647.

- ^ Wu XW, Muzny DM, Lee CC, Caskey CT (January 1992). "Two independent mutational events in the loss of urate oxidase during hominoid evolution". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 34 (1): 78–84. Bibcode:1992JMolE..34...78W. doi:10.1007/BF00163854. PMID 1556746. S2CID 33424555.

- ^ Ames BN, Cathcart R, Schwiers E, Hochstein P (November 1981). "Uric acid provides an antioxidant defense in humans against oxidant- and radical-caused aging and cancer: a hypothesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 78 (11): 6858–62. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.6858A. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.11.6858. PMC 349151. PMID 6947260.

- ^ Ghaemi-Oskouie F, Shi Y (April 2011). "The role of uric acid as an endogenous danger signal in immunity and inflammation". Current Rheumatology Reports. 13 (2): 160–6. doi:10.1007/s11926-011-0162-1. PMC 3093438. PMID 21234729.

- ^ "Pegloticase Drug Approval Package". US FDA. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Wössmann W, Schrappe M, Meyer U, Zimmermann M, Reiter A (March 2003). "Incidence of tumor lysis syndrome in children with advanced stage Burkitt's lymphoma/leukemia before and after introduction of prophylactic use of urate oxidase". Annals of Hematology. 82 (3): 160–5. doi:10.1007/s00277-003-0608-2. PMID 12634948. S2CID 27279071.

- ^ Stevenson WS, Hyland CD, Zhang JG, Morgan PO, Willson TA, Gill A, Hilton AA, Viney EM, Bahlo M, Masters SL, Hennebry S, Richardson SJ, Nicola NA, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Roberts AW, Alexander WS (September 2010). "Deficiency of 5-hydroxyisourate hydrolase causes hepatomegaly and hepatocellular carcinoma in mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (38): 16625–30. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716625S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1010390107. PMC 2944704. PMID 20823251.

- ^ Thyrion L, Portelli J, Raedt R, Glorieux G, Larsen LE, Sprengers M, Van Lysebettens W, Carrette E, Delbeke J, Vonck K, Boon P (July 2016). "Disruption, but not overexpression of urate oxidase alters susceptibility to pentylenetetrazole- and pilocarpine-induced seizures in mice". Epilepsia. 57 (7): e146-50. doi:10.1111/epi.13410. PMID 27158916.

- ^ Yeh AC, Brunner AM, Spitzer TR, Chen YB, Coughlin E, McAfee S, Ballen K, Attar E, Caron M, Preffer FI, Yeap BY, Dey BR (May 2014). "Phase I study of urate oxidase in the reduction of acute graft-versus-host disease after myeloablative allogeneic stem cell transplantation". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 20 (5): 730–4. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.02.003. PMID 24530972.

- ^ Nguyen T, Zelechowska M, Foster V, Bergmann H, Verma DP (August 1985). "Primary structure of the soybean nodulin-35 gene encoding uricase II localized in the peroxisomes of uninfected cells of nodules". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 82 (15): 5040–4. Bibcode:1985PNAS...82.5040N. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.15.5040. PMC 390494. PMID 16593585.

- ^ Doniselli, N.; Monzeglio, E.; Dal Palù, A.; Merli, A.; Percudani, R. (2015). "The identification of an integral membrane, cytochrome c urate oxidase completes the catalytic repertoire of a therapeutic enzyme". Scientific Reports. 5: 13798. Bibcode:2015NatSR...513798D. doi:10.1038/srep13798. PMC 4562309. PMID 26349049.