Tudor London

| Tudor London | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1485–1603 | |||

Map of London prior to 1561 by Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg in "Civitates Orbis Terrarum" | |||

| Location | London | ||

| Monarch(s) | Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey, Mary I, Elizabeth I | ||

| Key events | English Reformation, English Renaissance theatre | ||

Chronology

| |||

| History of London |

|---|

| See also |

|

|

The Tudor period in London started with the beginning of the reign of Henry VII in 1485 and ended in 1603 with the death of Elizabeth I. During this period, the population of the city grew enormously, from about 50,000 at the end of the 15th century[1] to an estimated 200,000 by 1603, over 13 times that of the next-largest city in England, Norwich.[2] The city also expanded to take up more physical space, further exceeding the bounds of its old medieval walls to reach as far west as St. Giles by the end of the period.[3] In 1598, the historian John Stow called it "the fairest, largest, richest and best inhabited city in the world".[4]

Topography

The area within the medieval walls, known as the City of London, featured timber-framed houses, often with upper storeys jutting out over the pavement. Two such surviving London houses from this period include the King's House inside the Tower of London, and Staple Inn.[5] During this period, London grew outside the old City boundaries. In futile attempts to check urban sprawl, repeated ordnances forbade the building of new houses on less than 4 acres (16,000 m2) of ground in 1580, 1583, and 1593, applying to land as far as Chiswick or Tottenham.[6] These laws had the unintended consequence that landlords within the medieval walls began subdividing their buildings as much as possible, and landowners outside the walls were encouraged not to build well, but to build quickly and surreptitiously.[6] In 1605, just after the end of the period, it has been estimated that 75,000 people lived in the City of London while 115,000 in the surrounding "liberties", such as St. Martin's-le-Grand, Blackfriars, Whitefriars, etc.[6]

The East End of London developed during this period, due to enclosures driving farmers off their land and into cities, and the lack of oversight from London's guilds, allowing businesses to continue without regulation.[6] The topographer and city historian John Stow recalled that Petticoat Lane in his youth had run among fields, flanked with hedgerows, but had become "a continual building of garden houses and small cottages" and Wapping "a continual street or filthy straight passage with alleys of small tenements".[6] By the end of the period, Whitechapel had transformed from a rural area to a hive of industry, with tanneries, slaughterhouses, breweries and foundries.[7]

The first maps of London were made in this period. One is by George Hoefnagel and Frans Hogenberg. It was published in 1572, but shows the city as it was around 1550.[8] The Agas map, attributed to the surveyor Ralph Agas, was made around 1561.[9] John Norden made maps of the City and Westminster in his Speculum Britanniae in 1593.[10] In 1598, John Stow published his Survey of London, a thorough topographical and historical description of the City.[11]

Palaces and mansions

The number of royal palaces in London expanded dramatically in this period, mostly due to building efforts under Henry VIII. Several palaces that existed prior to the period were also enlarged.[12] The Palace of Westminster was severely damaged by fire in 1512, and ceased to be a home for the royal family, being instead used as offices or chambers for the monarch to summon Parliament.[13] The Tower of London was used as a place from which Tudor monarchs processed to Westminster Abbey for their coronations, and as a place of imprisonment and execution, notably of high-ranking prisoners such as Anne Boleyn, Catherine Howard, and Lady Jane Grey.[14] 48 known cases of torture took place here between 1540 and 1640.[15] Eltham Palace was the childhood home of Henry VIII, where he was taught music and languages by his tutor, John Skelton.[16] He had it enlarged between 1519 and 1522.[17] Shene Palace burned down in 1497[18] and was rebuilt under Henry VII as Richmond Palace, featuring gilded domes and pinnacles. Both Henry VII and Elizabeth I died there.[19] Greenwich Palace was also rebuilt under Henry VII; and Henry VIII, Mary I, and Elizabeth I were born there.[20][21][22]

Hampton Court Palace was built by Henry VIII's advisor, Thomas Wolsey, and acquired in 1529 by Henry, who set about turning it into a sprawling pleasure palace, with tennis courts, bowling alleys, a tiltyard, Great Kitchens and a Great Hall. It is where his third wife, Jane Seymour, died; where his son, Edward VI, was born; and where he married his sixth wife, Catherine Parr.[23] Henry also acquired York Place from Wolsey, which he massively enlarged into Whitehall Palace,[24] with a tiltyard and tennis court,[12] and a royal mews for horses, carriages and hunting falcons close to Charing Cross.[25] It was where he died in 1547.[26] In 1531, Henry seized the St. James monastic leper hospital to rebuild as St. James's Palace,[27][28] and he had Nonsuch Palace built in 1538.[29] In 1543, Henry gave Chelsea Manor House to his sixth wife Catherine Parr, where she would continue to reside after his death in 1547.[30] In the same year, he had the Great Standing built in his hunting grounds at Epping Forest.[30]

From 1515, Henry VIII had Bridewell Palace built outside the City walls;[21] in 1553, Edward VI gave it to the City of London to be converted into a workhouse, the first such institution in Europe.[31] Its officers were given the authority to roam alehouses, cock-fighting pits, gambling dens and skittle-alleys, seizing homeless, unemployed or disorderly people and detaining them in Bridewell.[32]

Westminster Abbey owned a large estate in Hampstead where the mansion Belsize House was built some time before 1550.[18] The Archbishop of Canterbury had the gatehouse to his Lambeth Palace completed in 1501,[33] and the Bishop of London rebuilt his main manor house, Fulham Palace, from 1510.[13] In 1514, the manor of Tottenham was bought by William Compton, who rebuilt Bruce Castle.[21] Along the Strand was a series of mansions, including Somerset House,[34] Hungerford House, the Savoy Palace, Arundel Place, Cecil House,[25] and Durham Place, where Lady Jane Grey married Guildford Dudley in 1553.[35] Many of these were the houses of bishops or abbots at the beginning of the period, but transferred into the hands of secular aristocrats in the 1530s and 1540s.[24] The chancellor Thomas More had a mansion built in Chelsea, in which he lived in the 1520s.[28] Eastbury Manor House near Barking was constructed 1556–1578 for Clement Sysley.[9] Thomas Gresham had Osterley Park built around 1576, and Christopher Hatton had Hatton House built in Holborn in 1577.[36] The London merchant Richard Awsiter had a manor house built in Southall in Ealing in 1587.[37]

Other building work

Lincoln's Inn Hall was built 1489–1492, and was frequented by the politician and lawyer Thomas More.[38] Henry VII had the Henry VII Chapel added to Westminster Abbey between 1503 and 1510, and is buried inside with his wife, Elizabeth of York.[39] His grandchildren, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I, were also later buried inside.[40] The gatehouse to St. John Clerkenwell priory was completed in 1504, and still stands today.[18] The Prospect of Whitby pub, then known as the Devil's Tavern, was supposedly built in 1520 on Wapping Wall.[41] In 1561, lightning struck Old St Paul's Cathedral. The roof was repaired, but the 500 ft (150 m) spire was never replaced. Middle Temple Hall was built around 1570 and was frequented by Elizabeth I.[42]

Disasters often necessitated rebuilding work: great fires are recorded in 1485, 1504, 1506, and 1538.[43] In 1506, a great storm blew off tiles on houses and the weathervane on top of St. Paul's Cathedral.[44] In 1544, 1552, 1560 and 1583, stores of gunpowder exploded in London, often killing several people as well as damaging buildings.[45] In April 1580 there was some damage to chimneys and walls in the Dover Straits earthquake of 1580.[46]

Demography

At the end of the 15th century, London's population has been estimated at around 50,000.[1] By 1603, that number ballooned to an estimated 200,000, over 13 times that of the next-largest city in England, Norwich.[2] Between 1523 and 1527, a national tax was levied which yielded £16,675 from the inhabitants of London, more than the total amount yielded from the next 29 cities in England.[47]

Most Londoners married in their early or mid-twenties. Families who lived around Cheapside had four children on average, but in the poorer area of Clerkenwell, the average was only two and a half.[48] It is estimated that half of all children did not reach the age of 15.[48] The average height for male Londoners was 5'7½" (172 cm) and the average height for female Londoners was 5'2¼" (158cm).[49]

Plague hit so badly in 1563 in London that the local authorities began to compile death statistics for the first time in the Bills of Mortality. In that year, 20,372 were recorded dead in London across the whole year, 17,404 of whom died of the plague. Some years were much less dangerous: in 1582, only 6,930 deaths were recorded, of which 3,075 were from the plague, but in 1603 the total was 40,040, of which 32,257 died of the plague.[50]

Immigrants arrived in London not just from all over England and Wales, but from abroad as well. In 1563, the total of foreigners in London was estimated at 4,543, by 1568 it was 9,302 and by 1583 there was 5,141.[51][52] Nearly 25% of foreigners lived in villages outside London, inside the city French hatters stayed in Southwark, silk-weavers in Shoreditch and Spitalfields; whereas Dutch printers based themselves in Clerkenwell.[52] Protestants came to London fleeing persecution in Catholic countries such as Spain, France, and Holland. In 1550, the chapel at St. Anthony's Hospital was converted into a French church, and the chapel at Austin Friars into a Dutch church, given special licence to operate outside of the conventions of the Church in England.[53] This period also saw the first-known large-scale migration to London from Ireland. Irish migrants often settled in Wapping and St. Giles-in-the-Fields. Since they were mostly Catholic, they were not welcomed by the Protestant Elizabeth I, who in 1593 banned Irish migrants unless they were homeowners, domestic servants, lawyers, or university students.[10] Although Jews had been banned from England in the 13th century, there was a small community of 80-90 Portuguese Jews living in London during the reign of Elizabeth I.[54]

The period sees London's first portrait of a named black person, the royal trumpeter John Blanke, who performed at the courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII.[55] Aside from Blanke, a few black people appear in written records, such as the "blakemor" who arrived with Philip II of Spain when he came to London to marry Mary I, and an African needlemaker who worked on Cheapside.[56]

In 1600, an ambassador arrived in London from modern-day Morocco called Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud, seeking an alliance between the King of Barbary and Elizabeth I. He brought a retinue of 17 other Muslim men with him, and had a portrait painted during his visit.[57]

In 1602, one judge declared that there were 30,000 "idle persons and masterless men" (i.e., vagrants) living in London.[58]

The Thames

The Thames is the main river in London, and its main trade route to Europe and the wider world. It was both wider and shallower than it is today, and in 1564 it froze over so completely that Elizabeth I and her courtiers held an archery practice on the ice.[59] In this period, there was only one bridge- London Bridge- which was frequently congested,[25] so using wherries (small ferry-boats) to cross the river and go upstream or downstream was an important means of transportation within London, with an estimated 2,000 on the river.[60] Due to its importance for trade, the Thames was lined with small wharfs within London, particularly on the north bank between London Bridge and the Tower of London.[25] Most of these small wharfs were dedicated to one particular kind of trade- for example, Beare Quay for the ships coming from Portugal, Gibson's Quay for lead and tin, and Somers Quay for merchants from Flanders.[61] In 1559, a decree outlined the legal quays along the riverside, and mandated that all imports should be declared at Custom House.[9]

Around 1513, royal dockyards are established at Woolwich and Deptford to construct a national fleet. The first commission at Woolwich was the Henry Grace à Dieu, then the largest ship in the world.[13]

London Bridge

In this period, London Bridge was very different to today, lined on both sides with houses and shops up to four storeys tall. At the south end was a drawbridge which allowed tall ships to pass the bridge and acted as a defensive mechanism for the city.[59] In 1579, the tower holding the drawbridge mechanism was replaced with Nonsuch House, a pre-fabricated mansion built in the Netherlands.[59] South of Nonsuch House was the Great Stone Gate, where the heads of traitors such as Thomas More were displayed.[62]

Governance

The monarch had much more direct power to pass bills and change laws than today. Most Tudor monarchs summoned Parliament once a year, often to the Palace of Westminster, although Elizabeth I only summoned them ten times over her 45-year reign.[63]

The City of London was governed by the Court of Aldermen, a group of officials, each representing a division of the City called a ward.[64] Before 1550, there were 25 wards, with Southwark being added to make 26 in that year.[65] Each year, the aldermen chose one of their number to act as Lord Mayor. The legislative branch of the City leadership was the Common Council, which had over 200 members.[64][66] The administration of the City was based in the Guildhall, where it still stands.

Religion

At the beginning of the period, London contained 46 monasteries, nunneries, priories, abbeys, and friaries.[67] London's monastic communities included Greyfriars, Blackfriars, Austin Friars, the Charterhouse, St. Bartholomew-the-Great, Holy Trinity Priory, St. Mary Overy, Westminster Abbey, St. Helen's Bishopsgate, St. Saviour Bermondsey, Crossed Friars,[68] White Friars,[69] and St. Mary Graces.[69] In the surrounding area was Merton Priory, Barking Abbey, Bermondsey Abbey, Syon Abbey,[70] St. John Clerkenwell,[71] Lesnes Abbey,[72] Kilburn Priory,[73] Holywell Priory, St. Giles' Hospital, and St. Mary's Nunnery.[69] A Franciscan monastery was attached to Greenwich Palace in 1480.[21] Many wealthy Londoners left bequests to these institutions in their wills, and so they came to own large amounts of land in London. By 1530, about a third of all land within the city walls was owned by the Church.[74] London was also home to individuals with their own vows of monasticism, such as a hermit who lived on Highgate Hill, and another on St. John Street.[13]

In order to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, in the 1530s Henry VIII passed a series of Acts which broke away the Church in England from the Catholic Church in Rome, making him the Supreme Head of the Church in England.[75] In April 1534, every male Londoner was required to swear the Oath of Succession, in which they agreed to recognise the king's annulment.[75] In the monastery of London Charterhouse, the Carthusian monks refused to acknowledge Henry as head of the church, and four of them including their prior, John Houghton, were hanged, drawn and quartered.[76] The monastery was seized by the Crown, dissolved, and acquired by Edward North and later Thomas Howard, who was also executed for treason in 1572.[77]

Other monastic houses were dissolved in a less bloody fashion, but their considerable lands and buildings were still given or sold off to aristocrats and politicians- for example, Lord Cobham acquired Blackfriars Priory; the Marquess of Winchester built Winchester House on the site of Holy Trinity Aldgate, and Lord Dudley acquired St. Giles' Hospital.[27] Covent Garden, which was farmland belonging to Westminster Abbey, was granted to the Earl of Bedford.[78] Some monastic sites Henry seized for himself, such as the hospital that became St. James's Palace, and land belonging to Westminster Abbey which he turned into Hyde Park.[27] It is estimated that the monastic lands Henry seized were worth three times the land he already owned.[79] By 1551, the Venetian ambassador, Giacomo Soranzo, wrote of London that it was "disfigured by the ruins of a multitude of churches and monasteries".[27]

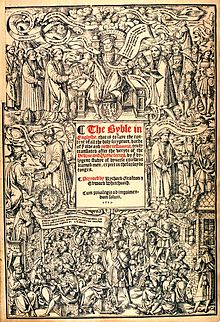

In 1535, an officially sanctioned English Bible was published. In 1539, six copies of the Great Bible were placed in St. Paul's Cathedral where anyone could read them or read them aloud to others.[80] Churches were also physically reformed, with jewels, rood lofts and statues of saints being removed. Sometimes these were taken down by officials, but in other churches, such as St. Margaret Pattens, reformist mobs destroyed these objects.[81] Under Edward VI, Protestant reforms were made such as the abolition of chantry chapels and the removal of saints' images and stained glass.[26]

After 1550, the building of new churches in London stopped for over 70 years, with St. Giles-without-Cripplegate being finished in 1550, and the next new construction being after the end of the period in 1623 with the Queen's Chapel near St. James' Palace.[82]

When the Catholic Mary I came to the throne in 1554, many of the Protestant reforms were reversed, but monastery lands were not returned to the Church.[83] While some Londoners were quick to restore saints' images and rood screens to their churches, others vehemently opposed the restoration of Catholic traditions. The parson of St. Ethelburga's, John Day, twice was put in the pillory and his ears nailed to it for speaking ill of the new queen, and in 1554 a dead cat dressed in the robes of a Catholic priest was found hanging on the gallows in Cheapside.[84]

Trade and industry

During the Tudor period, London was rapidly rising in importance amongst Europe's commercial centers, and its many small industries were booming, especially weaving. Trade expanded beyond Western Europe to Russia, the Levant, and the Americas. This was the period of mercantilism. In 1486, the Fellowship of Merchant Adventurers of London was formed, a company trading with the Low Countries.[85] From the 1550s, joint-stock companies, mostly formed of Londoners, were formed with monopolies on trades to various parts of the world, including the Muscovy Company (1555), the Eastland Company (1579), the Venice Company (1583), the Levant Company (1592), and the East India Company (1600).[86]

Markets were an important system of trade, with many taking place around the City. In 1565, Thomas Gresham founded a new mercantile exchange- a sort of early shopping centre-[87] which was awarded the title the "Royal Exchange" by Queen Elizabeth in 1571.[42] London's main market was on Cheapside.[87] Booksellers and stationers sold their goods in St. Paul's Churchyard.[87] The Stocks market was held next to St. Mary Woolchurch Haw and in 1543, it had 25 fishmongers and 18 butchers.[88]

There were also annual fairs held at various places in London, involving large markets and entertainments. One of the most well-known was Bartholomew Fair, held in Smithfield on land belonging to the priory of St. Bartholomew-the-Great.[89] After the priory was dissolved, the land was acquired by Richard Rich, who continued the annual fair.[89] It was visited by the German tutor Paul Hentzner in 1598, who described the Worshipful Company of Merchant Taylors gathering at the Hand and Shears pub in preparation for checking the measures of the goods on sale at the fair.[89]

London merchants also obtained goods through privateering. From 1562, vessels were increasingly given a "letter of marque" that permitted them to raid foreign vessels. In 1598, half of all English privateer vessels were from London.[90] One famous privateer who rose to prominence in this period was Francis Drake, who circumnavigated the globe in his ship Golden Hind, returning to London in 1581 and being knighted on the deck of his ship in Deptford.[91] A special dock was built in Deptford to house the ship, where it was available to be viewed by tourists.[92]

During the latter half of the 16th century, there was an increase in poverty as the cost of living increased while wages were fixed by the government, this caused crowds of poor people seeking work in the city including beggars.[52]

Health and medicine

Prior to the Reformation, hospitals were run by monastic institutions. At the beginning of the period, London had five principal hospitals, totalling somewhere between 350 and 400 beds. They were St. Bartholomew's in Smithfield; St. Thomas' in Southwark; St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate, which specialised in maternity care; St. Elsyng Spital, which specialised in the homeless blind; and St. Mary Bethlehem, commonly known as Bedlam, which specialised in mental illness.[93] Many of these hospitals also functioned as shelters for the homeless or the infirm. In 1505, Henry VII founded St. John the Baptist's Hospital on the site of the Savoy Palace.[94] These were all dissolved in the Reformation, and mostly given over to the City to re-establish them as secular hospitals, except for St. Mary-without-Bishopsgate and St. Elsying Spital, which were permanently closed.[95] The estate of the Savoy Hospital was given to St. Thomas'.[96]

Individual physicians and surgeons may have received a medical degree from a university or had been granted a licence after taking an apprenticeship, however many were completely unlicensed.[97] By the end of the period, there was a medical practitioner (a physician, surgeon or apothecary) for every 400 people in London.[98]

Outside the City, there were leper hospitals from at least 1500 at Hammersmith and Knightsbridge.[33]

The very first year of the period coincided with a serious outbreak of a disease known as the "sweating sickness" which generally killed its victims within a single day. Two Lord Mayors died within four days.[64] London would continue to suffer epidemics of the sweating sickness throughout the period.[99] There were also repeated outbreaks of plague. During these epidemics, wealthy people would leave London for the season until it was safe to return, meaning that the disease disproportionately affected the poor.[100] 1518 saw England's first nationwide quarantine orders, following similar ordinances in Venice and Paris.[101] In London, houses with infected people were quarantined for 40 days, and those infected were ordered to carry a white stick when outside, so that others could avoid them.[101] London lagged behind other European cities in health measures, leading Soranzo to write that there was "some little plague in England well nigh every year, for which they are not accustomed to make sanitary provisions".[102]

The Royal College of Physicians was founded in 1518 at the house of noted physician Thomas Linacre in Knightrider Street. It had the authority to regulate practitioners and even imprison unlicensed practitioners for up to twenty days.[103]

Crime and law enforcement

A serious outbreak of violence in this period occurred on Evil May Day in 1517, when a xenophobic riot broke out among London apprentices. Young London men stormed the houses and workshops of French and Flemish craftspeople.[104] The Duke of Norfolk led an armed militia into the city to disperse the rioters. 278 were arrested, with 15 later being executed.[104]

In 1533, the Buggery Act was passed, making sex acts such as sodomy and bestiality illegal for the first time in England. One of the first to be convicted under this law was Walter Hungerford, 1st Baron Hungerford of Heytesbury, who was beheaded at Tower Hill in 1540. At first, the Act was mostly used to convict monks; in 1546, the churchman John Bale called the clergy "none other than sodomites and whoremongers all the pack".[105] Later in the period, theatres and schools were thought to be particular hot-beds of buggery: in 1541, the headmaster of Eton College, Nicholas Udall, was questioned in London and confessed to committing buggery with one of his students, Thomas Cheyne. He was imprisoned in Marshalsea before being later appointed headmaster of Westminster School.[106]

In 1536, the Member of Parliament Robert Pakington became one of the first recorded Londoners to be murdered with a handgun. No-one was ever convicted of the crime.[107]

On certain days of the weeks and at religious festivals, Londoners were forbidden from eating meat, with only fish allowed. In 1561, a butcher in Eastcheap was fined £20 for killing three cows during Lent, and in 1563, two women were put in the stocks at St. Katherine's by the Tower for refusing to abide by the rule.[108]

In 1585, a thieves' school was found in Billingsgate, where trainee pickpockets would attempt to take coins from a purse. Hanging on the wall next to the purse was a bell which would ring if the students performed poorly.[109]

The end of the period saw the development of a type of boisterous, semi-criminal working-class woman called the "roaring girl". Although the most famous roaring girls, such as Mary Frith, lived in the Stuart period, there are early Tudor examples such as Long Meg, a possibly-fictional woman depicted in the pamphlet The Life and Pranks of Long Meg of Westminster. Long Meg ran a tavern in Islington, dressed as a man, and fought with any man who dared challenge her.[110]

Punishments

Public corporal and capital punishment were both used widely in London. Hangings commonly took place at Tyburn, but gallows could be erected at any convenient location close to a murder scene.[111] People convicted of piracy were often hanged on the Wapping foreshore of the Thames at low tide, with the bodies left on the gallows until the tide washed over them three times.[112] Beheadings are generally reserved for the nobility, and often take place on Tower Hill.[113] Tudor London saw the only two instances of an execution method not used at any other time in England- boiling alive, a fate reserved for poisoners. Both executions took place at Smithfield.[114]

The pillory was a common punishment for low-level offences, with a pillory being erected at Cheapside, among other places.[115] The stocks were similar, but held a person's legs rather than their hands and face.[116] Public whippings took place for offences such as petty theft, sedition, or having an illegitimate child. For example, in 1561, a man was whipped through the streets in Westminster, the City, across London Bridge, and into Southwark, for forging documents;[117] and in the same year, two men recently released from Bedlam Hospital and Marshalsea Prison claimed to be the risen Christ and Saint Peter, and were both whipped through the streets.[118] Another punishment designed for public humiliation was the tumbrel, a cart carrying the offender that was wheeled through the streets. In 1560, two men and three women were put on the tumbrel in London for fornication, and in 1563, a physician called Christopher Langton was carted down Cheapside for being caught "with two young wenches at once".[119] In addition, mob justice took place throughout the period. For example, in 1561, a man was chased by an angry mob for stealing a child's necklace, and was beaten to death in Mark Lane.[115]

London had a debtors' prison called the Fleet, for the imprisonment of people who could not pay their creditors. It housed about fifty inmates, and was notorious for its poor conditions and disease. Inmates had to pay for food, and pay rent for a separate room.[120]

Treason

Several high-profile nobles and even royalty were executed for treason in London in this period. Also, there were several large rebellions against Tudor monarchs which either took place in London or ended with the rebels being imprisoned or executed in London.

In 1497, Perkin Warbeck, who claimed to be the true heir to the throne, Richard, Duke of York, was captured and paraded through the streets of London before being imprisoned in the Tower and executed in 1499 on Tower Hill.[18] In the same year, a group of rebels from Cornwall marched on London in protest of high taxes. They were defeated at Blackheath in the Battle of Deptford Bridge, and their leader, Lord Audley, was beheaded on Tower Hill.[18]

Several Londoners opposed Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn, including the prophetess Elizabeth Barton. She predicted that Henry would die within six months of his marriage to Anne, and although her prophecy did not come true, she was executed at Tyburn in 1534 and her head put on a spike at London Bridge.[22] In 1536, Anne herself was imprisoned in the Tower on suspicion of being unfaithful in her marriage. She was beheaded in the grounds of the Tower of London in 1536.[73] Henry's fifth wife, Catherine Howard, was also beheaded for adultery in 1541.[30]

In 1548, the Privy Council and the City of London attempted to depose Edward Seymour, who was acting as Lord Protector, ruling on behalf of the child king Edward VI before he came of age. Seymour was captured and sent to the Tower of London before being exiled to Richmond Palace[121] and executed on Tower Hill in 1552.[32]

In 1553, Edward VI named his Protestant cousin Lady Jane Grey as his successor rather than his Catholic half-sister Mary. After his death, Mary marched on London with an army to meet the forces of the Duke of Northumberland in Shoreditch. Londoners refused to support Northumberland, who was imprisoned along with Jane and her husband, Guildford Dudley. All were later executed for treason.[35]

In 1554, a rebellion began in Kent led by Thomas Wyatt in protest of Mary I's marriage to Philip II of Spain. The rebels marched on London, and the Londoners sent out to defend the city instead defected to the side of the rebels. Mary went to the London Guildhall and gave a speech where she accused Wyatt of attempting to seize the Tower where wealthy Londoners kept their money, and rallied a force to prevent Wyatt's men from crossing London Bridge. The artillery of the Tower fired at London Bridge and St. Mary Overy, where the rebels were gathered, and so Wyatt took his force west to cross the river at Kingston-upon-Thames instead, marching towards London from the west. Once again, the gates of London are held closed against him, and Wyatt is defeated at Temple Bar and later executed.[122] Mary suspected her sister Elizabeth of involvement, but Wyatt refused to implicate her, and Elizabeth was released from the Tower.[123]

In 1579, Elizabeth was on the royal barge at Greenwich when a bullet hit her helmsman. She gave him her scarf and told him to be glad, as he stopped a bullet meant for her. A man called Thomas Appletree confessed to the crime, saying that he had been showing off to some friends by firing randomly and hadn't meant to hit the royal barge. He was sentenced to be hanged close to the scene of his crime, and was given a royal reprieve at the last moment.[124]

The reign of Elizabeth saw Catholics being executed for treason in large numbers. In 1581, the Jesuit priest Thomas Campion was imprisoned in a tiny cell in the Tower of London called the Little Ease before being hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn,[91] and another Jesuit priest, Robert Southwell, was imprisoned in Newgate in 1595 before being executed in the same fashion.[125]

1586 saw the execution of Anthony Babington for his part in a plot to overthrow Elizabeth and replace her with her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots. He and thirteen co-conspirators were executed near Holborn, possibly at Lincoln's Inn Fields.[109] After the first seven were disembowelled still alive, the crowd was so disgusted that the remainder were permitted to die by hanging before being disembowelled.[111] Another person executed for treason, albeit on much scantier evidence, was the Portuguese-Jewish royal physician, Roderigo Lopes, who was hanged in 1594.[125]

The last major revolt of the period was Essex's Rebellion in 1601, where Robert Devereux gathered together a group of rebels at Essex House. When the Lord Chief Justice and other officers arrived, Essex imprisoned them and took his forced to the City. However, the Lord Mayor's forces drove him back to his house, where he was arrested, and later executed at the Tower.[126]

Heresy

Religious persecution occurred under every monarch in this period. Between 1485 and 1553, 102 heretics were burned at the stake around the country, many at Smithfield, the usual London location for burnings.[127]

The Lollard movement demanded the translation of the Bible into English, a practice considered heretical at the time. Illicit English translations of the New Testament were smuggled into London from Germany and Antwerp,[128] and even the dean of St. Paul's Cathedral was threatened with prosecution for translating the Lord's Prayer into English.[129]

Under Henry VIII, those executed for heresy were just as likely to be Protestant as Catholic. In 1540, six people were executed at Smithfield on the same day without trial or even charges read against them. Three were Protestants and were burned at the stake, and three were Catholic and were hanged.[30] In 1546, the staunch Protestant Anne Askew was tortured on the rack at the Tower of London and burned at the stake in Smithfield for heresy.[26]

In the reign of Mary I, 78 were burned in London alone.[127] After her reign, John Foxe collected stories of Protestant martyrs in his Acts and Monuments, published in Aldersgate.[130] Under Elizabeth I, Catholics were less likely to be burned for heresy, but more likely to be executed for treason. From 1584, anyone who became a Catholic priest after Elizabeth's accession was declared guilty of treason.[125] Instead, those burned for heresy were more likely to be from radical Protestant sects such as Anabaptism. In 1575, two Dutch Anabaptists from Aldgate are burned at the stake.[54]

Courts

As well as advising the monarch on affairs of state, the privy council also acted as a law court called Star Chamber, meeting in the Palace of Westminster. It tried people who had breached the privy council's orders, duellists, conspirators, rioters, libellers, etc., and had the distinction of being the only body with the power to authorise the use of torture. Defendants called before the Star Chamber did not have the right to speak, or even to hear the evidence against them; some were merely summoned to hear the judgement passed on them.[131]

Also at the Palace of Westminster there were four royal courts: the Court of the Exchequer, the Court of the Queen's Bench, the Court of Common Pleas, and the Court of Chancery. Parliament itself also acted as a court for some treason cases.[132] They tried cases in bursts called "sessions", which took place every three months. Thomas Platter wrote that "rarely does a law day take place in London in all the four sessions pass without some twenty to thirty persons, both men and women, being gibbeted".[111]

Education

At the beginning of the period, the best London schools were run by monastic institutions such as St. Anthony's Hospital in Threadneedle Street and St. Peter's Cornhill.[133] St Paul's Cathedral School was refounded by John Colet in 1510 for 153 boys to study for free. By 1525 it was so popular that applications had to be restricted to London boys only.[134] In 1531, the Nicholas Gibson Free School was founded on Ratcliffe Highway by a wealthy grocer.[135]

In the reigns of Edward VI and Elizabeth I, many grammar schools were founded to replace educational establishments that had been run by monks and dissolved.[108] Christ's Hospital was founded in 1552, on the grounds of Greyfriars.[136] In 1558, Enfield Grammar School was refounded.[9] In 1560, Elizabeth refounded Westminster School with 40 free places for boys known as the Queen's Scholars.[108] Kingston Grammar School and St. Olave's Grammar School were both set up in 1561,[108] Highgate School in 1565,[137] Harrow School in 1572, and Queen Elizabeth's School in Chipping Barnet in 1573.[138]

Livery companies also founded their own schools, such as the Mercers' School in Old Jewry in 1541,[30] and the Merchant Taylors' School on Suffolk Lane in 1561.[108]

When Thomas Gresham died in 1579, he provided for the foundation of Gresham College in his will, which offers free lectures on astronomy, divinity, geometry, law, medicine, music and rhetoric. After his widow died in 1596, their house in Bishopsgate was used as a lecture hall.[46]

Due to the large number of schools, Londoners were more likely to be literate than people in the rest of the country. About 75% of adult men and 25% of adult women were literate by the end of the period.[139]

Culture

Literature

The Tudor period in London, particularly during the reign of Elizabeth I, is considered a golden age of English literature, especially poetry and plays. The writer Thomas More joined Lincoln's Inn in 1496, where he met humanists and scholars such as John Colet, Thomas Linacre, and Desiderius Erasmus.[38] He later joined the court of Henry VIII and became one of his chief advisers. His writings include Utopia, a travelogue of a fictional perfect country where all proeprty is held in common and war has been abolished.[17] The period saw a notable increase in female writers and scholars, such as Mildred Cecil.[140]

At the beginning of the period, the printing press in London was in its infancy, with London's first press, run by William Caxton, having been set up only nine years prior. In 1492 it was taken over by Wynkyn de Worde and moved from Westminster to Fleet Street.[141] Published works were subject to strict censorship by the Crown beginning in the 1530s. From 1557, all published works were required to be registered with the Stationers' Company in London, and from 1586 printing presses were only allowed to operate in London, Oxford and Cambridge.[142]

Almost all well-educated people wrote poetry, but notable poets who lived in London include Philip Sidney, who wrote Arcadia, Astrophel and Stella, and A Defence of Poesy; Edmund Spenser, who wrote The Shepheardes Calender and The Faerie Queene; and William Shakespeare.[143] In 1566, Isabella Whitney, a servant in London who teaches herself to write, becomes the first English woman to publish a book of verse.[144]

At the beginning of the period, theatre in London mostly took the form of miracle plays based on Biblical stories.[145] However, during the reign of Elizabeth I, these were banned for being too Catholic, and secular plays performed by travelling companies became popular instead.[146] These companies began by performing at galleried coaching inns and upper-class houses before beginning to build their own permanent theatres in London, the first known example being the Red Lion in Whitechapel.[146] In 1574, theatres were banned from within the city walls,[138] so instead they were built in the outskirts, such as The Theatre and The Curtain to the east in Shoreditch; The Rose, The Swan and The Globe to the south in Southwark; The Fortune to the north; and the Blackfriars to the west.[146] The most famous playwright of the age is William Shakespeare, who wrote 25 of his plays including Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and A Midsummer Night's Dream during the Tudor period, but others include Christopher Marlowe, Thomas Kyd, Thomas Nashe, Thomas Dekker, and Ben Jonson.[147] The masquerade developed as an aristocratic form of theatre during this period, with the first known performance taking place in Greenwich Palace in 1516.[21]

Music

Almost all Londoners would have been able to play an instrument or sing, and many pubs would have had live music. In 1587, the satirist Stephen Gosson wrote that "London is so full of unprofitable pipers and fiddlers that a man can no sooner enter a tavern than two or three cast of them hang at his heels to give him a dance ere he depart."[148] Important composers who lived in London include Thomas Tallis, William Byrd and John Bull, all of whom were employed by Elizabeth I at the Chapel Royal despite being Catholics.[149] Tallis' Spem in Alium was performed at Nonsuch Palace by a massed chorus of eight choirs.[149]

Sports and games

Under the laws such as the Archery Acts of 1542, 1566 and 1571, all boys over the age of 7 were required to be taught archery, and all men aged between 17 and 60 were required to keep a bow and four arrows at home.[150] Archery butts existed around London, including at Moorfields, for the purpose of practice.[151] In 1583, 3,000 people took part in an archery competition in Smithfield, with the competitors including fake nobles such as the "Duke of Shoreditch" and "Marquis of Clerkenwell".[109] Fencing schools to teach young gentlemen the art of the duel existed across the city, including at Ely Place, Greyfriars, Bridewell, Artillery Gardens, Leadenhall and Smithfield.[152] In August, wrestling competitions were held at Finsbury Fields.[153] Football was a much more violent and lawless game than today, with the writer Philip Stubbes calling it "a friendly kind of fight". In 1582, a man was killed playing football in West Ham.[154]

Popular cockfighting rings existed in Whitehall Palace, Jewin Street, Shoe Lane and St. Giles in the Fields, with large amounts of money being gambled every Sunday.[155] In Paris Garden in Southwark there were bear-baiting and bull-baiting contests, where a chained bear or bull is set upon by a pack of mastiffs. Even Elizabeth I visited in 1599 to see the spectacle.[156] Other baiting pits existed near Whitehall and in Islington.[36]

Thomas More attributed crime to "unlawful games" such as "dice, cards, tables, tennis, bowls, quoits", and these games were banned at various points throughout the period. In 1528, Thomas Wolsey authorised men to search people's homes and prosecute those found in possession of "dice, cards, bowls, closhes [nine-pin bowling skittles], tennis balls".[114] However, Henry VII and Henry VIII were both tennis-players, and a tennis court was available at All-Hallows-the-Less from 1542.[151]

Art

The highest-status artists of the period were generally Europeans who have moved to London, such as the sculptor Pietro Torregiano, who was commissioned to create the effigies of Henry VII, Elizabeth of York, and Margaret Beaufort in Westminster Abbey; and Hans Holbein, who became court painter to Henry VIII and created many of the iconic portraits of the period.[157]

See also

References

- ^ a b Porter, Stephen (2016). Everyday Life in Tudor London. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4456-4586-5.

- ^ a b Mortimer, Ian (2012). The Time Traveller's Guide to Elizabethan England. London: The Bodley Head. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-1-84792-114-7.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 27.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 56-57.

- ^ a b c d e Pevsner 1973, p. 52.

- ^ Barratt 2012, p. 60.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 2000, p. 96.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 106.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 108.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2012, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Lipscomb, Suzannah (2012). A Visitor's Companion To Tudor England. Ebury Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780091944841.

- ^ Lipscomb 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Lipscomb 2012, p. 45.

- ^ a b Lipscomb 2012, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e Richardson 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Lipscomb 2012, p. 51-52.

- ^ Richardson, John (2000). The Annals of London: A Year-by-Year Record of a Thousand Years of History. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-520-22795-8.

- ^ a b c d e Richardson 2000, p. 79.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 84.

- ^ Lipscomb 2012, p. 54-56.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d Mortimer 2012, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d Pevsner, Nikolaus (1973). The Buildings of England: London- The Cities of London and Westminster. Revised by Bridget Cherry (3rd ed.). Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin. p. 50. ISBN 0140710124.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 82.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 222.

- ^ a b c d e Richardson 2000, p. 87.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 112.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 92.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 76.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 53.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 121.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 101.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 105.

- ^ a b Lipscomb 2012, p. 35.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Lipscomb 2012, p. 24-26.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 80.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 99.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 66.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 67.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 162.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 102.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 11.

- ^ a b Porter 2011, p. 157.

- ^ Werner, Alex (1998). London Bodies. London: Museum of London. p. 108. ISBN 090481890X.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 279-280.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 116.

- ^ a b c Pearse, Malpas (1969). Stuart London. Internet Archive. London, Macdonald. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-356-02566-7.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 110.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2012, p. 92.

- ^ Kaufmann, Miranda (2017). Black Tudors: The Untold Story. London: Oneworld Publications. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-78607-184-2.

- ^ Kaufmann 2017, p. 11.

- ^ British Library. "Portrait of the Moroccan Ambassador to Queen Elizabeth I". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 55-56.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 204.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 29-30.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 31.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Porter 2016, p. 13.

- ^ Porter, Stephen (2011). Shakespeare's London: Everyday Life In London, 1580-1616. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Amberley. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-84868-200-9.

- ^ Porter 2011, p. 23.

- ^ Barratt, Nick (2012). Greater London: The Story of the Suburbs. London: Random House Books. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-84794-532-7.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 83-86.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 86.

- ^ Barratt 2012, p. 57-58.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 77.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 81.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 85.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 89.

- ^ a b Lipscomb 2012, p. 30.

- ^ Lipscomb 2012, p. 30-31.

- ^ Lipscomb 2012, p. 32-33.

- ^ Barratt 2012, p. 66.

- ^ Barratt 2012, p. 58.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 102.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 103.

- ^ Pevsner 1973, p. 57.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 122.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 124.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 49.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 144.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 42.

- ^ a b c Addison, William Wilkinson (1953). English Fairs and Markets. London: B.T. Batsford. pp. 50–52.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Porter 2016, p. 146.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 103.

- ^ Roche, Thomas William Edgar (1973). The Golden Hind. New York: Praeger. p. 20. ISBN 9780213164386.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 64-65.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 68.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 111.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 113.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 288.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 287.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 69.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 72.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 70-71.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 73.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 63.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 54.

- ^ Ackroyd, Peter (2018). Queer City: Gay London from the Romans to the Present Day. New York: Abrams Press. p. 43. ISBN 9781419730993.

- ^ Ackroyd 2018, p. 54.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 98.

- ^ a b c d e Richardson 2000, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 104.

- ^ Ackroyd 2018, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2012, p. 302.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 303.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 305.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 76.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2012, p. 292.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 310.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 307.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 308.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 311.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 306.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 89.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 125.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 93.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 293.

- ^ a b c Richardson 2000, p. 107.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 109.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 126.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 96.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 94.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 127-128.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 294.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 301.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 61.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 61-62.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 83.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 114.

- ^ Richardson 2000, p. 98.

- ^ a b Richardson 2000, p. 100.

- ^ Porter 2011, p. 162.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 68.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 51.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 104.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 346-347.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 69.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 351.

- ^ a b c Mortimer 2012, p. 351-353.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 354.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 336.

- ^ a b Mortimer 2012, p. 339.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 326-327.

- ^ a b Porter 2016, p. 77.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 329.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 330.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 330-331.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 333.

- ^ Mortimer 2012, p. 334-335.

- ^ Porter 2016, p. 58.