1990 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1990 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | May 24, 1990 |

| Last system dissipated | October 21, 1990 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Gustav |

| • Maximum winds | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 956 mbar (hPa; 28.23 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 16 |

| Total storms | 14 |

| Hurricanes | 8 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 1 |

| Total fatalities | 171 total |

| Total damage | $152.61 million (1990 USD) |

| Related articles | |

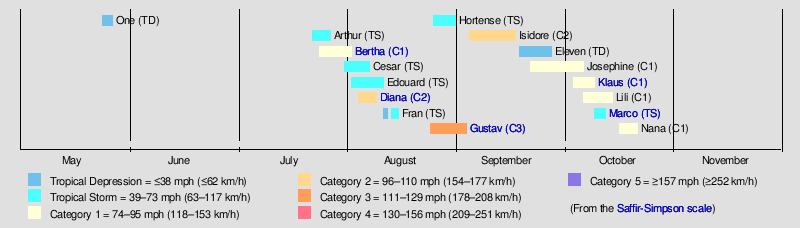

The 1990 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active Atlantic hurricane season since 1969, with a total of 14 named storms. The season also featured eight hurricanes, one of which intensified into a major hurricane. It officially began on June 1, 1990, and lasted until November 30, 1990.[1] These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. However, tropical cyclogenesis can occur prior to the start of the season, as demonstrated with Tropical Depression One, which formed in the Caribbean Sea on May 24.

Though active, the season featured relatively weak systems, most of which stayed at sea. The 1990 season was unusual in that no tropical cyclone of at least tropical storm strength made landfall in the United States for the first time since the 1962 season, although Tropical Storm Marco weakened to a depression just before landfall.

Only a few tropical cyclones caused significant impacts. Hurricane Diana killed an estimated 139 people in the Mexican states of Veracruz and Hidalgo, while also causing approximately $90.7 million in damage. Hurricane Klaus brought flooding to Martinique and caused torrential rainfall across the southeastern United States after combining with Tropical Storm Marco and a frontal boundary. As a result of effects from Diana and Klaus, both names were retired following the season. Overall, the storms of the season collectively caused 171 fatalities and approximately $157 million in damage.

Seasonal forecasts

Pre-season forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

| NOAA[2] | April 20, 1990 | 14 | 6 | Unknown |

| CSU[3] | June 5, 1990 | 11 | 7 | 3 |

| Record high activity[4] | 30 | 15 | 7 (Tie) | |

| Record low activity[4] | 1 | 0 (tie) | 0 | |

| Actual activity | 14 | 8 | 1 | |

Forecasts of hurricane activity are issued before each hurricane season by noted hurricane experts such as Dr. William M. Gray and his associates at Colorado State University (CSU). A normal season as defined by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), has eleven named storms, of which six reach hurricane strength, and two major hurricanes.[5] In April 1990, it was forecast that six storms would reach hurricane status, and there would be "three additional storms" from the previous year, which would indicate 14 named storms. The forecast did not specify how many hurricanes would reach major hurricane status.[2] In early June 1990, CSU released their predictions of tropical cyclonic activity within the Atlantic basin during the 1990 season. The forecast from CSU called for 11 named storms, seven of which to intensify into a hurricane, and three would strengthen further into a major hurricane.[3]

Seasonal summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1,[1][6] but activity in 1990 began five days earlier with the formation of Tropical Depression One on May 25. It was an above average season in which 16 tropical depressions formed. Fourteen depressions attained tropical storm status, and eight of these attained hurricane status. There was only one tropical cyclone to reach major hurricane status (Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale),[7] which was slightly below the 1950–2005 average of two per season.[5] Unusually, the season featured no landfalling tropical storms in the United States. This was only the sixth such occurrence known, the other seasons being 1853, 1862, 1864, 1922, and 1962.[8] Overall, the storms of the season collectively caused 171 deaths and approximately $153 million in damage.[8][9][10][11] The last storm of the season, Hurricane Nana, dissipated on October 21,[7] over a month before the official end of the season on November 30.[1][6]

The activity in the first two months of the season were limited in tropical cyclogenesis, with the second tropical depression of the season not developing until July 22. Following that, the season was very active, and there was a quick succession of tropical cyclone development from late-July to mid-August. The Atlantic briefly remained dormant, and activity resumed on August 24 with the development of Tropical Depression Eight (Hurricane Gustav). Although August was a very active month, there were only two named storms in September, both of which became hurricanes. Activity in October was higher than average, with five tropical cyclones either forming or existing in that month. Following an active October, no tropical cyclogenesis occurred in November.[7]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 97,[12] which is slightly above the mean value of 96.[13] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is the threshold for tropical storm strength.[14]

Systems

Tropical Depression One

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | May 24 – May 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

Tropical Depression One formed on May 25 from a weak low pressure area to the west of Jamaica, which had been producing scattered showers over the island during the preceding days.[7][15] The depression moved across Cuba shortly after forming, although the convection was located to the east of its poorly defined center. As it headed toward Florida, it was absorbed by an approaching cold front.[7]

The depression did not cause significant damage. In Florida, the depression was forecast to ease drought conditions that persisted for about two years.[16] While crossing Cuba, the depression dropped heavy rainfall, and predictions stated that precipitation amounts could reach as high as 10 in (250 mm), but the greatest amount measured was at 6 in (150 mm) east of Havana.[17] Heavy rainfall also occurred across much of south Florida, peaking at 6.20 in (157 mm) at the Royal Palm Ranger Station in Everglades National Park.[18] While the depression was affecting south Florida, the National Weather Service issued "urban flood statements" warning of flooded streets in mainly low-lying areas, especially in Dade and Broward counties. Standing water on many Florida expressways caused automobile accidents, especially in Dade County, where 28 accidents were reported.[19]

Tropical Storm Arthur

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 22 – July 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 995 mbar (hPa) |

The second tropical depression of the season developed on July 22 from a tropical wave nearly midway between the Lesser Antilles and Cape Verde. The depression slowly intensified, and was eventually upgraded to Tropical Storm Arthur, two days later. On July 25, Tropical Storm Arthur crossed the Windward Islands chain,[20] and it was noted that the storm made landfall on Tobago.[21] Emerging into the Caribbean Sea, Arthur nearly attained hurricane status on July 25. Thereafter, wind shear began increasing over Arthur, and a weakening trend began after peak intensity. As Arthur headed further into the Caribbean Sea, it significantly weakened and was downgraded to a tropical depression on July 27. Later that day, Air Force reconnaissance and satellite imagery did not show a low-level circulation, indicating that Arthur had degenerated into open tropical wave 130 mi (210 km) southeast of Kingston, Jamaica.[20]

Shortly after Arthur became a tropical storm on July 24, a tropical storm warning was issued for Trinidad, Tobago, and Grenada; six hours later, it was extended to the Grenadines. About 24 hours later, all of the tropical storm warnings were discontinued. As Arthur headed further into the Caribbean Sea, a tropical storm watches and warnings were issued for Hispaniola and Puerto Rico on July 26. All of the tropical storm watches and warnings were discontinued after Arthur weakened to a tropical depression.[22] After Arthur made landfall on Tobago, several landslides occurred, and a major bridge had collapsed; electrical and water services were significantly disrupted. Damage was also reported on Grenada, where two bridges were damaged, electricity and telephone service was disrupted, and crops were affected as well. In addition, Arthur caused damage to four hotels and hundreds of houses.[23] Wind gusts on the island of Grenada reportedly reached 55 mph (89 km/h).[24] As Arthur passed south of Puerto Rico, there were reports of strong winds and heavy rainfall. Heavy rainfall was also reported on the south coast of Haiti as Arthur approached the country.[25]

Hurricane Bertha

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 24 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 973 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa, and after interacting with a cold front and an area of low pressure, developed into a subtropical depression on July 24, offshore of North Carolina near Cape Hatteras. The subtropical depression slowly acquired tropical characteristics, and was reclassified as Tropical Depression Three on July 27. On the following day, the National Hurricane Center upgraded the depression to Tropical Storm Bertha. It drifted northeast and became a hurricane 500 mi (800 km) west-southwest of Bermuda on July 29. As Bertha continued parallel to the East Coast of the United States, it had experienced strong wind shear and was downgraded back to a tropical storm later on July 29.[26] However, by July 30, Air Force reconnaissance flights reported at hurricane-force winds, and Bertha had re-intensified into a hurricane at that time. After becoming a hurricane again, Bertha continued northeastward, but transitioned into an extratropical cyclone over Nova Scotia on August 2.[27]

Nine deaths were attributed to Bertha, including six crew members of the Greek freighter Corazon who perished off the Canadian coast after their ship broke up. Another fatality was caused when one person fell off the ship Patricia Star and into the Atlantic; the other two deaths were from two people drowning in north Florida.[28] Damage to crops and a suspension bridge were reported from Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island; this damage totaled to $4.427 million (1990 CAD; $3.912 million 1990 USD).[10]

Tropical Storm Cesar

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 31 – August 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

While Bertha was approaching Atlantic Canada, a tropical wave emerged into an Atlantic from the west coast of Africa, and quickly developed into Tropical Depression Four approximately 335 mi (539 km) south of Cape Verde. The depression headed northwestward due to the weakness of a subtropical ridge and slowly intensified. While the depression was well west of Cape Verde, it intensified into Tropical Storm Cesar on August 2. Cesar continued on the generally northwestward path and no significant change in intensity occurred, as it peaked at 50 mph (80 km/h) shortly after becoming a tropical storm. Later in its duration, wind shear significantly increased, causing the low-level circulation to be removed from the deep convection on August 6, and Cesar weakened back to a tropical depression as a result. As it was weakening to a tropical depression, Cesar became nearly stationary, and turned abruptly eastward. On the following day, Cesar dissipated almost 1,150 mi (1,850 km) east-southeast of Bermuda.[29]

Tropical Storm Edouard

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 2 – August 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

A frontal wave formed near the Azores in early August. When thunderstorm activity grew near its center, it was deemed a subtropical depression on August 2 just east of the Azores. Associated with an upper-level cold low, it intensified into a subtropical storm on August 3, although water temperatures were cooler than what is usually required for tropical cyclogenesis. It tracking westward and passed near Graciosa before weakening back to a depression on August 4. The depression executed a small cyclonic loop, developing deep and organized convection near the circulation. Late on August 6, it transitioned into Tropical Depression Six. The depression moved northeastward toward the Azores, intensifying into Tropical Storm Edouard on August 8. Shortly thereafter it reached peak winds of 45 mph (72 km/h), and subsequently it moved past the northern Azores. On August 10, Edouard weakened again to depression status, and became extratropical on the following day. The remnants of Edouard dissipated on August 13, a few hundred miles west of Portugal.[30][31]

Much of the western Azores reported winds of at 35 mph (56 km/h). The island of Horta reported winds gusts from 35 to 65 mph (56 to 105 km/h). Lajes Air Force Base on Terceira Island reported a maximum wind gust of 38 mph (61 km/h). Also a tower on the island of Terceira reported sustained winds at 50 mph (80 km/h), while a gusts as high as 67 mph (108 km/h) were recorded.[32]

Hurricane Diana

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 4 – August 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave uneventfully crossed the Atlantic Ocean and entered the Caribbean Sea either late July or early August 1990. As the system entered the southwest Caribbean, it began to further develop, and became Tropical Depression Five on August 4. The depression headed northwestward, and intensified enough to be upgraded to Tropical Storm Diana on August 5. After becoming a tropical storm, Diana continued to quickly intensify, and maximum sustained winds were 65 mph (105 km/h) before landfall occurred in Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Quintana Roo, on the Yucatán Peninsula. Diana weakened somewhat over the Yucatán Peninsula, but was still a tropical storm when it entered the Gulf of Mexico. While over the Gulf of Mexico, Diana again rapidly intensified, and became a hurricane on August 7. Later that day, Diana further strengthened into a Category 2 hurricane, and peaked with winds of 100 mph (160 km/h).[33] Only two hours, Diana made landfall near Tampico, Tamaulipas, at the same intensity. After moving ashore, Diana rapidly weakened, and had deteriorated to a tropical storm only four hours after landfall. By August 8, Diana weakened back to a tropical depression near Mexico City. Diana briefly entered the Eastern Pacific Basin on August 9, but was not re-classified, and it rapidly dissipated at the south end of the Gulf of California.[33]

In preparations for Diana, there were several tropical storm watches and warning issued along the Yucatán Peninsula and several areas along the Gulf Coast of Mexico; hurricane watches and warnings were also put into effect.[34] While crossing the Yucatán Peninsula, Diana produced near-tropical storm force winds, and heavy rainfall, but not damage or fatalities. However, the mainland of Mexico fared much worse, where torrential rainfall caused mudslides in the states of Hidalgo and Veracruz. As a result of heavy rainfall, many houses were destroyed, and approximately 3,500 became homeless. Diana also produced high winds across Mexico, which toppled tree and fell electricity poles, leaving many without telephone service and block several roads. In addition, the remnants of Diana brought rainfall to the southwestern United States. Contemporary reports indicated that 139 people had been killed, with an additional 25,000 people being injured. Damage as a result of Diana was estimated at $90.7 million.[9]

Tropical Storm Fran

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 11 – August 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

On August 11, a tropical wave developed into the seventh tropical depression of the season, while situated several hundred miles southwest of Cape Verde. The depression moved rapidly westwards, and intensified to just under tropical storm status on August 12. However, later that day, the depression began to lose its low-level circulation, while deep convection was diminishing. As a result, the depression became "too weak to classify" for Dvorak technique, and the system had degenerated back into a tropical wave early on August 13. After weakening back to a tropical wave, the system quickly re-organized, and re-developed into a tropical depression twelve hours later. Later that day, the depression further intensified, and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Fran. No significant change in intensity occurred after Fran became a tropical storm and maximum sustained winds never exceeded 40 mph (64 km/h).[35] By the next day, Fran made landfall on Trinidad at the same intensity.[36] While on Trinidad, Fran significantly interacted with the South American mainland, and quickly dissipated on August 15.[35]

After Fran became a tropical storm on August 13, a tropical storm warning was issued for Trinidad, Tobago, and Grenada. Simultaneously, a tropical storm watch came into effect for Barbados and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. As Fran was passing through the Windward Islands, the tropical storm watch was discontinued. Only two hours before Fran dissipated, the tropical storm warning was discontinued for Trinidad, Tobago, and Grenada.[37] As a result of Fran, only heavy rains were reported on the Windward Islands.[36] Light rainfall was reported on Trinidad, peaking at 2.6 in (66 mm). In addition, wind gusts were reported up to 29 mph (47 km/h).[38]

Hurricane Gustav

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 24 – September 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min); 956 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression developed from a tropical wave approximately 1,000 mi (1,600 km) east of Barbados on August 24. After forming, the depression moved westward and on the next day intensified into a tropical storm on the following day. After becoming a tropical storm, Gustav continued to intensify as it headed west-northwestward. Intensification into a hurricane occurred on August 26, as the storm began slowly curving northward under the influence of a trough. After reaching Category 2 intensity, Gustav was affected by wind shear, and weakened, but eventually re-intensified. The hurricane ultimately peaked as a Category 3 hurricane on August 31,[39] and was also the most intense tropical cyclone of the season, in addition to being the only major hurricane in the Atlantic that year.[7] Around the time of attaining peak intensity, Gustav began a fujiwhara interaction with nearby Tropical Storm Hortense. After attaining peak intensity on August 31, Gustav weakened back, at nearly the same rate as it had intensified, and deteriorated to a tropical storm on September 2. By September 3, Gustav transitioned into an extratropical cyclone, 230 mi (370 km) south of Iceland.[40]

Gustav initially appeared as a significant threat to the Lesser Antilles, which was devastated by Hurricane Hugo about a year prior. As a result, several hurricane watches and warnings were issued on August 27, but all were discontinued later that day as Gustav turned northward.[41] The only effects reported on the Lesser Antilles were large swells, light winds, and light rains.[42] Following the passage of Gustav, no damage or fatalities were reported.[40]

Tropical Storm Hortense

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 25 – August 31 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 993 mbar (hPa) |

The ninth tropical depression of the season developed from a tropical wave 700 mi (1,100 km) west-southwest of Cape Verde on August 25. The depression headed west-northwestward, while slowly intensifying and establishing better-defined upper-level outflow. By August 26, the depression intensified enough to be upgraded to Tropical Storm Hortense. After becoming a tropical storm, Hortense was steered nearly due north, under the influence on an upper-level low. Hortense later headed generally northwestward, after the upper-level low degenerated into a trough and moved eastward. Although intensification was somewhat slow, Hortense managed to peak as a 65 mph (105 km/h) tropical storm on August 28. On August 29, nearby Hurricane Gustav was rapidly intensifying, and began to significantly affect Hortense with increasing vertical wind shear. Hortense weakened, with the storm degenerating into a tropical depression on August 30. Further weakening occurred, and Hortense dissipated on August 31 roughly 805 mi (1,295 km) east-southeast of Bermuda.[43]

Hurricane Isidore

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 4 – September 17 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 100 mph (155 km/h) (1-min); 978 mbar (hPa) |

A vigorous tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa on September 3. It quickly developed an area of deep convection with a well-defined circulation, which prompted it being classified a tropical depression on September 4. At the time it was situated hundreds of miles south of Cape Verde at a very southerly latitude of 7.2°N, making it the southernmost-forming tropical cyclone on record in the north Atlantic basin. Initial intensification was slow as the system moved northwestward, a movement caused by a large mid-level trough over the central Atlantic. On September 5 the NHC upgraded the depression to Tropical Storm Isidore. Subsequently, it intensified at a faster rate, becoming a hurricane on September 6. The following day, satellite estimates from the Dvorak technique suggested a peak intensity of 100 mph (160 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 978 mbar (hPa; 28.88 inHg).[44]

After peaking, Isidore entered a region of stronger upper-level winds and quickly weakened. By September 8 it had deteriorated into a tropical storm, although re-intensification occurred after the shear decreased. An eye feature redeveloped in the center of the convection, and Isidore re-intensified into a hurricane on September 9. It ultimately reached a secondary peak intensity of 90 mph (140 km/h). Isidore's motion slowed, briefly becoming stationary, although it remained a hurricane for several days. Cooler waters imparted weakening to a tropical storm on September 16, and the next day it became extratropical to the east of Newfoundland.[44] There were a few ships that came in contact with Hurricane Isidore, one of which reported hurricane-force wind gusts. The storm never approached land during its duration, and no damage or casualties were reported.[44]

Tropical Depression Eleven

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 18 – September 27 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

On September 18, Tropical Depression Eleven formed midway between Africa and the Lesser Antilles from a tropical wave. Ship and reconnaissance aircraft observations reported that the depression almost reached tropical storm strength. However, it was torn apart by strong upper-level winds until it dissipated on September 27. The system never affected land.[7]

Hurricane Josephine

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 21 – October 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 980 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave exited the coast of Africa on September 16 with copious convection. It tracked westward, developing into Tropical Depression Twelve on September 21 while located a few hundred miles west of Cape Verde. Without intensifying further, the depression turned northward, due to a weakness caused by the deepening of a 200 mbar cut-off low near the Iberian Peninsula. Under the influence of a building high pressure area, the depression turned to a northwest and later westward drift. It into Tropical Storm Josephine on September 24, although increased wind shear from a trough weakened the storm back to a tropical depression on September 26. It remained weak for several days, gradually turning to the north due to a weak trough over the northwestern Atlantic. On October 1, another high pressure area halted its northward movement, causing Josephine to turn to the east. That day, it re-intensified into a tropical storm as it began to execute a small cyclonic loop. An approaching trough caused Josephine to accelerate north-northeastward, and with favorable conditions it intensified into a hurricane on October 5, after existing nearly two weeks.[45][46]

Josephine intensified slightly more on October 5, attaining its peak intensity later that day with maximum sustained winds of 85 mph (137 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 980 mbar (980 hPa; 29 inHg). A large mid-latitude storm began developing on October 5, and Hurricane Josephine accelerated around the east periphery on the system. Josephine weakened back to a tropical storm early on October 6, while moving to the north of the mid-latitude system. After tracking near the mid-latitude cyclone, Tropical Storm Josephine transitioned into an extratropical storm on October 6 before being absorbed by it. The mid-latitude cyclone later developed into Hurricane Lili.[45][46]

Hurricane Klaus

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 3 – October 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 985 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into Tropical Depression Thirteen on October 3 around 115 mi (185 km)/h) east of Dominica. The depression rapidly intensified into a tropical storm, and was classified as Tropical Storm Klaus only six hours later. Because Klaus was in an area of weak steering current, it was drifting west-northwestward. On October 5, Klaus briefly intensified into a hurricane, and passed only 12 mi (19 km) east of Barbuda later that day. By the following day, Klaus had weakened back into a tropical storm. After weakening to a tropical storm, Klaus began to accelerate, while turning westward. Klaus became significantly affected by wind shear, as it weakened to a tropical depression to the north of Puerto Rico on October 8. Later that day, deep convection began to re-developed near the low-level circulation of Klaus, and it had re-intensified into a tropical storm.[47] As Klaus tracked northwestward near the Bahamas on October 9, it was absorbed by an area of low pressure, which would eventually develop into Tropical Storm Marco.[48]

Since Klaus passed very close to the Leeward Islands, tropical storm watches and warnings were issued, as well as hurricane watches and warning, starting on October 4. In addition, tropical storm watches and warnings were also issued for the British and United States Virgin Islands, and the Bahamas. After several watches and warnings were issued, all were discontinued by October 9, around the time when Klaus was absorbed by the area of low pressure.[49] In Martinique, flooding caused seven fatalities, and displaced 1,500 other people. Heavy rainfall also occurred on other Leeward Islands, with estimates as high as 15 in (380 mm) of precipitation. However, no effects were reported in the Bahamas.[8] The remnants brought large waves and heavy rainfall to southeastern United States, which caused four deaths when a dam burst in South Carolina. In total, Klaus caused 11 fatalities,[8][48] but only $1 million in damage.[11]

Hurricane Lili

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 6 – October 14 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 987 mbar (hPa) |

A cold-core low which affected the latter stages of Josephine developed at the surface and became a subtropical storm on October 6, about 875 mi (1,408 km) southeast of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The subtropical storm moved southwest and slowly curved westward, nearly intensifying into a hurricane. On October 11, the subtropical storm finally acquired tropical characteristics. Simultaneously, the now-tropical cyclone intensified into a hurricane, and was re-classified as Hurricane Lili. After becoming a hurricane, Lili headed rapidly west-southwestward, and did not intensify past maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (121 km/h). After passing 140 mi (230 km) south of Bermuda later that day, Lili began to curve slowly northward, thereby avoiding landfall in the United States. While about 200 mi (320 km) east-southeast of Cape Hatteras, Lili weakened back to tropical storm intensity. Weakening to a tropical storm, Lili curved northeastward and accelerated toward Atlantic Canada.[50] However, Lili transitioned into an extratropical storm on October 14, just offshore of Nova Scotia. The post-tropical cyclone made landfall on Newfoundland soon afterwards.[51]

Lili posed a threat to Bermuda, and a hurricane warning as the storm approached, but only gusty winds and light rainfall was reported.[52] As Lili continued westward, it had also posed a significant threat to the East Coast of the United States, since some of the computer models did not predict a northward curve. As a result, several hurricane watches and warnings were issued from Little River Inlet, South Carolina, to Cape Henlopen, Delaware.[53] However, Lili later curved northward, and only caused minor coastal erosion in North Carolina and rainfall in Pennsylvania.[54] Lili began impacting Atlantic Canada as it was transitioning an extratropical cyclone, and the storm reportedly caused strong winds in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland.[55] No damage total or fatalities were reported.[51]

Tropical Storm Marco

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 9 – October 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 989 mbar (hPa) |

As Klaus was dissipating, a new cold low developed over Cuba and developed down to the surface as a tropical depression on October 9. The depression emerged over the Straits of Florida, and quickly intensified into a tropical storm on October 10. After becoming a tropical storm, Marco steadily intensified and eventually peaked with winds of 65 mph (105 km/h). Marco headed towards Florida, and remained just offshore of the western coast and nearly made landfall near St. Petersburg, Florida, on October 12. However, Marco continued to interact with land, and weakened to a tropical depression before actually making landfall near Cedar Key, Florida, with winds of 35 mph (56 km/h). It rapidly weakened over land, and dissipated in Georgia later that day.[56] Although it had dissipated, Marco added to the heavy rainfall already brought to the southeastern states by the remnants Hurricane Klaus.[57]

Although only a depression at final landfall, this was officially counted as a tropical storm hit on the United States as much of the circulation was on land before landfall in the area of St. Petersburg, Florida.[58] In preparations for Marco, a tropical storm warning was issued for nearly the entire Gulf and Atlantic coast of Florida.[59] In Florida, Marco caused flooding damage to houses and roads, in addition to producing tropical storm force winds across the state. However, Marco is more notable for the impact from the remnants, especially in Georgia and South Carolina, where rainfall from the storm peaked at 19.89 in (505 mm) near Louisville, Georgia. In combination with the remnants of Hurricane Klaus, Marco caused heavy rainfall in South Carolina, causing a dam to burst, leading to three fatalities. Several more fatalities were caused by the remnants of Marco and Klaus, and the system caused 12 deaths.[8][60] It also caused $57 million in damage, most of it from damage or destruction of residences in Georgia.[8]

Hurricane Nana

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 16 – October 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 989 mbar (hPa) |

On October 7, a vigorous tropical wave emerged off the coast of Africa near Cape Verde, and despite semi-favorable conditions, the wave did not develop initially, due to embedded westerlies, which caused the wave to remain disorganized, despite having deep convection. Six days later, the wave had reached the Lesser Antilles, and split, the northern portion of the wave then developed into Tropical Depression Sixteen on October 16. The depression rapidly intensified to a tropical storm, and then a hurricane the next day, receiving the name Nana. Development increased slightly and the system reached its peak intensity of 85 mph (137 km/h) that same day. Nana dissipated while heading southward on October 21.[61]

Nana initially posed a threat to Bermuda, and as a result, a hurricane watch was issued late on October 18. However, after Nana weakened to a tropical storm on October 20, the hurricane watch was downgraded to a tropical storm watch. Furthermore, Nana began to curve southeastward away from Bermuda, and later on October 20, the tropical storm watch was discontinued.[62] The only known effect from Nana on Bermuda was 0.33 in (8.4 mm) of rain.[63] Nana was a very small hurricane, the circulation probably being only 30–40 mi (48–64 km) wide.[64]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the north Atlantic in 1990.[65] This was the same list used for the 1984 season.[66] Storms were named Marco and Nana for the first time in 1990.

|

Retirement

The World Meteorological Organization retired the names Diana and Klaus from the Atlantic hurricane name lists following the 1990 season.[67] They were replaced with Dolly, and Kyle, respectively, for the 1996 season.[68]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 1990 Atlantic hurricane season. It includes their name, duration, peak classification and intensities, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1990 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | May 24 – 26 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1007 | Cuba, Southeastern United States | None | None | |||

| Arthur | July 22 – 27 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 995 | Greater Antilles, Windward Islands, Venezuela, Grenada, Jamaica, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico | Minimal | None | |||

| Bertha | July 24 – August 2 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 973 | Bahamas, East Coast of the United States, Bermuda, Atlantic Canada | $3.91 million | 9 | |||

| Cesar | July 31 – August 7 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | None | None | None | |||

| Edouard | August 2 – 11 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1003 | Portugal | None | None | |||

| Diana | August 4 – 9 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 980 | Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Belize, Yucatán Peninsula, Mainland Mexico | $90.7 million | 139 | |||

| Fran | August 11 – 15 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1007 | Greater Antilles, Windward Islands, Venezuela | Minimal | None | |||

| Gustav | August 24 – September 3 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 956 | Lesser Antilles | None | None | |||

| Hortense | August 25 – 31 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 993 | None | None | None | |||

| Isidore | September 4 – 17 | Category 2 hurricane | 100 (155) | 978 | None | None | None | |||

| Eleven | September 18 – 27 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Josephine | September 21 – October 6 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 980 | None | None | None | |||

| Klaus | October 3 – 9 | Category 1 hurricane | 80 (130) | 985 | Lesser Antilles, Puerto Rico, Hispaniola, Turks and Caicos Islands, Bahamas, Southeastern United States | $1 million | 11 | |||

| Lili | October 6 – 14 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 987 | Bermuda, East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Canada | None | None | |||

| Marco | October 9 – 12 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 989 | Florida, Georgia, The Carolinas, East Coast of the United States | $57 million | 12 | |||

| Nana | October 16 – 21 | Category 1 hurricane | 85 (140) | 989 | Bermuda | Moderate | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 16 systems | May 24 – October 21 | 120 (195) | 956 | $153 million | 171 | |||||

See also

- Tropical cyclones in 1990

- 1990 Pacific hurricane season

- 1990 Pacific typhoon season

- 1990 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone season: 1989–90, 1990–91

- Australian region cyclone season: 1989–90, 1990–91

- South Pacific cyclone season: 1989–90, 1990–91

- South Atlantic tropical cyclone

- Mediterranean tropical-like cyclone

References

- ^ a b c "Hurricane season begins among dire predictions". The Hour. Associated Press. June 1, 1990. p. 3. Retrieved March 11, 2011.

- ^ a b "State's luck may wane, storm expect predicts". Gainesville Sun. Associated Press. April 21, 1990. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "Hurricane forecast says Florida sitting duck". Associated Press. June 6, 1990. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "North Atlantic Ocean Historical Tropical Cyclone Statistics". Fort Collins, Colorado: Colorado State University. Retrieved July 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "Background information: the North Atlantic Hurricane Season". Climate Prediction Center. May 27, 2010. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Dorst, Neil (January 12, 2010). "FAQ: When is hurricane season?". Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Avila, Lixion A. (August 1991). "Atlantic Tropical Systems of 1990" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 119 (8): 2027–2033. Bibcode:1991MWRv..119.2027A. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1991)119<2027:ATSO>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Mayfield, B. Max; Lawrence, Miles B. (August 1991). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1990". Monthly Weather Review. 119 (8): 2014–2026. Bibcode:1991MWRv..119.2014M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1991)119<2014:AHSO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Economic Effects of Mexican Natural Disasters (PDF) (Report) (in Spanish). Pan American Health Organization. 1990. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2009. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ a b "1990-Bertha". Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Glass, Robert (October 6, 1990). "Klaus Weakens, Moves Over Open Atlantic Waters". Associated Press.

- ^ "Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ "Extended range forecast of Atlantic seasonal hurricane activity and landfall strike probability for 2010" (PDF). Colorado State University. December 9, 2009. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 5, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ Landsea, Christopher W. (2019). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". Hurricane Research Division. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ "First depression of season forms". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. May 25, 1990. p. 4B. Retrieved March 1, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Marx, Anthony (May 26, 1990). "Depression dousing Caribbean". The News. p. 1C. Retrieved March 1, 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Depression may soak Florida, ease drought". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. May 26, 1990. p. 10A. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Roth, David (August 4, 2008). "Tropical Depression No. 1 – May 24–26, 1990". Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "South Florida gets drenching". Ocala-Star Banner. Associated Press. May 28, 1990. p. 3B. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Miles (1990). Tropical Storm Arthur Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ "2000 Hurricane Season" (DOC). World Meteorological Organization.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (1990). Tropical Storm Arthur Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 4. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Caribbean – Tropical Depression Arthur Jul 1990 UNDRO Information Reports 1–2. United Nations Department of Humanitarian Affairs (Report). ReliefWeb. July 26, 1990. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- ^ "Tropical Storm Arthur fades, regains gusto". The Victoria Advocate. Associated Press. July 27, 1990. p. 14A. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ "Jamaica to get storm". Kentucky New Era. Associated Press. July 27, 1990. p. 2A. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Bertha Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Bertha Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Bertha Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (1990). Tropical Storm Cesar Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ Case, Robert (1990). Tropical Storm Edouard Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Case, Robert A. (1990). Tropical Storm Edouard Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Case, Robert A. (1990). Tropical Storm Edouard Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Avila, Lixion (1990). Hurricane Diana Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Avila, Lixion (1990). Hurricane Diana Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 5. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Miles (1990). Tropical Storm Fran Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ a b "Tropical Storm Fran loses strength". The Telegraph-Herald. Associated Press. August 14, 1990. p. 2A. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (1990). Tropical Storm Fran Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 3. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ^ De Souza, G. (May 2001). "Tropical Cyclones Affecting Trinidad and Tobago, 1725 To 2000" (PDF). Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 23, 2005. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Gustav Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Gustav Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Gustav Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 8. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Staff Writer (August 27, 1990). "Gustav spares northeast Caribbean". United Press International.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (1990). Tropical Storm Hortense Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c Avila, Lixion (1990). Hurricane Isidore Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Case, Robert A. (1990). Hurricane Josephine Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Case, Robert A. (1990). Hurricane Josephine Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (1990). Hurricane Klaus Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Lawrence, Miles (1990). Hurricane Klaus Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Lawrence, Miles (1990). Hurricane Klaus Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 5. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Lili Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Lili Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Laxman, Leanne (October 12, 1990). "Hurricane Lili bearing down on North Carolina". Daily News. Associated Press. p. 7–A. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Gerrish, Hal (1990). Hurricane Lili Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 8. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Black, Marshall D. (October 15, 1990). "Heavy rains flood into Arendtsville". Gettysburg Times. p. 3A. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Canadian Tropical Cyclone Season Summary for 1990 (Report). Canadian Hurricane Centre. August 10, 2009. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (1990). Tropical Storm Marco Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Roth, David (September 26, 2006). "Tropical Storm Marco/Klaus – October 8–13, 1990". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. Archived from the original on January 3, 2011. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (1990). Tropical Storm Marco Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Mayfield, Max (1990). Tropical Storm Marco Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 11. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (October 14, 1990). "East Breathes Easier as Storms' Threat Pales". The New York Times. p. 123.

- ^ Avila, Lixion (1990). Hurricane Nana Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 1. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ Avila, Lixion (1990). Hurricane Nana Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 6. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Roth, David M. (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Avila, Lixion (1990). Hurricane Nana Preliminary Report (Report). National Hurricane Center. p. 2. Retrieved January 12, 2011.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1990. p. 3-6. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1984. p. 3-9. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1996. p. 3-7. Retrieved January 17, 2024.