Italo-Turkish War

| Italo-Turkish War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Scramble for Africa | |||||||||

Clockwise from top left: Battery of Italian 149/23 cannons; Mustafa Kemal with an Ottoman officer and Libyan mujahideen; Italian troops landing in Tripoli; an Italian Blériot aircraft; Ottoman gunboat Bafra sinking at Al Qunfudhah; Ottoman prisoners in Rhodes. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Mobilisation 1911:[2] 4 battalions Alpini, 7 battalions Ascari and 1 squadron Meharisti |

Initial:[3] ~8,000 regular Turkish troops ~20,000 local irregular troops Final:[3] ~40,000 Turks and Libyans | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

1,432 killed in action[4][5] 1,948 died of disease[4][6][5] 4,250 wounded[5] |

8,189 killed in action[7] ~10,000 killed in reprisals & executions[8] | ||||||||

| Events leading to World War I |

|---|

|

|

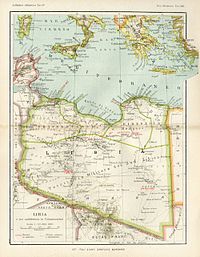

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War (Turkish: Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", Italian: Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911 to 18 October 1912. As a result of this conflict, Italy captured the Ottoman Tripolitania Vilayet, of which the main sub-provinces were Fezzan, Cyrenaica, and Tripoli itself. These territories became the colonies of Italian Tripolitania and Cyrenaica, which would later merge into Italian Libya.

During the conflict, Italian forces also occupied the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea. Italy agreed to return the Dodecanese to the Ottoman Empire in the Treaty of Ouchy[9] in 1912. However, the vagueness of the text, combined with subsequent adverse events unfavourable to the Ottoman Empire (the outbreak of the Balkan Wars and World War I), allowed a provisional Italian administration of the islands, and Turkey eventually renounced all claims on these islands in Article 15 of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne.[10]

The war is considered a precursor of the First World War. Members of the Balkan League, seeing how easily Italy defeated the Ottomans[11] and motivated by incipient Balkan nationalism, attacked the Ottoman Empire in October 1912, starting the First Balkan War a few days before the end of the Italo-Turkish War.[12]

The Italo-Turkish War saw some technological changes, most notably the use of airplanes in combat. On 23 October 1911, an Italian pilot, Capitano Carlo Piazza, flew over Turkish lines on the world's first aerial reconnaissance mission,[13] and on 1 November, the first aerial bomb was dropped by Sottotenente Giulio Gavotti, on Turkish troops in Libya, from an early model of Etrich Taube aircraft.[14] The Turks, using rifles, were the first to shoot down an airplane.[15] Another use of new technology was a network of wireless telegraphy stations established soon after the initial landings.[16] Guglielmo Marconi, the inventor of wireless telegraphy, came to Libya to conduct experiments with the Italian Corps of Engineers.

Background

Italian claims to Libya date back to the Ottoman defeat by the Russian Empire during the War of 1877–1878 and subsequent disputes thereafter. At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, France and the United Kingdom had agreed to the French occupation of Tunisia and British control over Cyprus respectively, which were both parts of the declining Ottoman state.

When Italian diplomats hinted about possible opposition to the Anglo-French maneuvers by their government, the French replied that Tripoli would have been a counterpart for Italy, which made a secret agreement with the British government in February 1887 via a diplomatic exchange of notes.[17] The agreement stipulated that Italy would support British control in Egypt, and that Britain would likewise support Italian influence in Libya.[18] In 1902, Italy and France had signed a secret treaty which accorded freedom of intervention in Tripolitania and Morocco.[19] The agreement, negotiated by Italian Foreign Minister Giulio Prinetti and French Ambassador Camille Barrère, ended the historic rivalry between both nations for control of North Africa. The same year, the British government promised Italy that "any alteration in the status of Libya would be in conformity with Italian interests". Those measures were intended to loosen Italian commitment to the Triple Alliance and thereby weaken Germany, which France and Britain viewed as their main rival in Europe.

Following the Anglo-Russian Convention and the establishment of the Triple Entente, Tsar Nicholas II and King Victor Emmanuel III made the 1909 Racconigi Bargain in which Russia acknowledged Italy's interest in Tripoli and Cyrenaica in return for Italian support for Russian control of the Bosphorus.[20] However, the Italian government did little to realise that opportunity and so knowledge of the Libyan territory and resources remained scarce in the following years.[citation needed]

The removal of diplomatic obstacles coincided with increasing colonial fervor. In 1908, the Italian Colonial Office was upgraded to a Central Directorate of Colonial Affairs. The nationalist Enrico Corradini led the public call for action in Libya and, joined by the nationalist newspaper L'Idea Nazionale in 1911, demanded an invasion.[21] The Italian press began a large-scale lobbying campaign for an invasion of Libya in late March 1911. It was fancifully depicted as rich in minerals and well-watered, defended by only 4,000 Ottoman troops. Also, its population was described as hostile to the Ottomans and friendly to the Italians, and they predicted that the future invasion would be little more than a "military walk".[12]

The Italian government remained committed into 1911 to the maintenance of the Ottoman Empire, which was a close friend of its German ally. Prime Minister Giovanni Giolitti rejected nationalist calls for conflict over Ottoman Albania, which was seen as a possible colonial project, as late as the summer of 1911.

However, the Agadir Crisis in which French military action in Morocco in July 1911 would lead to the establishment of a French protectorate, changed the political calculations. The Italian leadership then decided that it could safely accede to public demands for a colonial project. The Triple Entente powers were highly supportive. British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey stated to the Italian ambassador on 28 July that he would support Italy, not the Ottomans. On 19 September, Grey instructed Permanent Under-Secretary of State Sir Arthur Nicolson, 1st Baron Carnock that Britain and France should not interfere with Italy's designs on Libya. Meanwhile, the Russian government urged Italy to act in a "prompt and resolute manner".[22]

In contrast to its engagement with the Entente powers, Italy largely ignored its military allies in the Triple Alliance. Giolitti and Foreign Minister Antonino Paternò Castello agreed on 14 September to launch a military campaign "before the Austrian and German governments [were aware] of it". Germany was then actively attempting to mediate between Rome and Constantinople, and Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal repeatedly warned Italy that military action in Libya would threaten the integrity of the Ottoman Empire and create a crisis in the Eastern Question, which would destabilise the Balkan Peninsula and the European balance of power. Italy also foresaw that result since Paternò Castello, in a July report to the king and Giolitti, laid out the reasons for and against military action in Libya, and he raised the concern that the Balkan revolt, which would likely follow an Italian attack on Libya, might force Austria-Hungary to take military action in Balkan areas claimed by Italy.[23]

The Italian Socialist Party had a strong influence over public opinion, but it was in opposition and also divided on the issue. It acted ineffectively against military intervention. The future Italian fascist leader Benito Mussolini, who was then still a left-wing Socialist, took a prominent antiwar position. A similar opposition was expressed in Parliament by Gaetano Salvemini and Leone Caetani.[citation needed]

An ultimatum was presented to the Ottoman government, led by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), on the night of 26–27 September 1911. Through Austro-Hungarian intermediation, the Ottomans replied with the proposal of transferring control of Libya without war and maintaining a formal Ottoman suzerainty. That suggestion was comparable to the situation in Egypt, which was under formal Ottoman suzerainty but was under de facto control by the British. Giolitti refused.

Italy declared war on 29 September 1911.[24]

Military campaign

Opening maneuver

The Italian army was ill-prepared for the war and was not informed of the government's plans for Libya until late September. The army had a shortage of soldiers as the class of 1889 was demobilized before the war started. Military operations started with the bombardment of Tripoli on 3 October.[24] The city was conquered by 1,500 sailors, much to the enthusiasm of the interventionist minority in Italy. Another proposal for a diplomatic settlement was rejected by the Italians, and so the Ottomans decided to defend the province.[26]

On 29 September 1911, Italy published the declaration of their direct interest towards Libya. Without a proper response, the Italian forces landed on the shores of Libya on 4 October 1911. A considerable number of Italians were living within the Ottoman Empire, mostly inhabiting Istanbul, Izmir, and Thessaloniki, dealing with trade and industry. The sudden declaration of war shocked both the Italian community living in the Empire as well as the Ottoman government. Depending on the mutual friendly relations, the Ottoman Government had sent their Libyan battalions to Yemen in order to suppress local rebellions, leaving only the military police in Libya.[27]

Therefore, the Ottomans did not have a full army in Tripolitania. Many of the Ottoman officers had to travel there by their own means, often secretly, through Egypt since the British government would not allow Ottoman troops to be transported en masse through Egypt. The Ottoman Navy was too weak to transport troops by sea. The Ottomans organised local Libyans for the defence against the Italian invasion.[28]

Between 1911 and 1912, over 1,000 Somalis from Mogadishu, the capital of Italian Somaliland, served as combat units along with Eritrean and Italian soldiers in the Italo-Turkish War.[29] Most of the Somalian troops stationed would return home only in 1935, when they were transferred back to Italian Somaliland in preparation for the invasion of Ethiopia.[30]

Italian troops landing in Libya

The first disembarkation of Italian troops occurred on 10 October. Having no prior military experiences and lacking adequate planning for amphibious invasions, the Italian armies poured onto the coasts of Libya, facing numerous problems during their landings and deployments.[31] One of these problems was that the Ottoman vice admiral in 1911, Bucknam Pasha, was at first successfully blockading the Italians from landing on the Tripolitanian coast.[32]

The Italians believed that a force of 20,000 would be able to take over Libya. The force was able to capture Tripoli, Tobruk, Derna, Bengasi, and Homs between 3 and 21 October. However, the Italians suffered a defeat at Shar al-Shatt, with at least 21 officers and 482 soldiers dead. The Italians executed 400 women and 4,000 men through firing squads and hanging in retaliation.[33]

The corps was consequently enlarged to 100,000 men[34] who had to face 20,000 Libyans and 8,000 Ottomans. The war turned into one of position. Even the Italian utilisation of armoured cars[35] and air power, both among the earliest in modern warfare, had little effect on the initial outcome.[36] In the first military use of heavier-than-air craft, Capitano Carlo Piazza flew the first reconnaissance flight on 23 October 1911. A week later, Sottotenente Giulio Gavotti dropped four grenades on Tajura (Arabic: تاجوراء Tājūrā’, or Tajoura) and Ain Zara in the first aerial bombing in history.[37]

Trench phase

(from Italian weekly La Domenica del Corriere, 26 May – 2 June 1912).

Technologically and numerically superior Italian forces easily managed to take the shores. However, the Italians still could not penetrate deep inland.[38] The Libyans and Turks, estimated at 15,000, made frequent attacks day and night on the strongly-entrenched Italian garrison in the southern suburbs of Benghazi. The four Italian infantry regiments on the defensive were supported by the cruisers San Marco and Agordat. The Italians rarely attempted a sortie.[39]

An attack of 20,000 Ottoman and local troops was repulsed on 30 November with considerable losses. Shortly afterward, the garrison was reinforced by the 57th infantry regiment from Italy. The battleship Regina Elena also arrived from Tobruk. During the night of 14 and 15 December, the Ottomans attacked in great force but were repulsed with aid of the fire from the ships. The Italians lost several field guns.[39]

At Derna, the Ottomans and the Libyans were estimated at 3,500, but they were being constantly reinforced, and a general assault on the Italian position was expected. The Italian and Turkish forces in Tripoli and Cyrenaica were constantly reinforced since the Ottoman withdrawal to the interior enabled them to reinforce their troops considerably.[39]

Lacking a considerable navy, the Ottomans were not able to send regular forces to Libya and so the Ottoman government supported a great number of young officers to travel to the area in order to rally the locals and coordinate the resistance. Enver Bey, Mustafa Kemal Bey, Ali Fethi Bey, Cami Bey, Nuri Bey and many other Turkish officers managed to reach Libya, traveling under secret identities such as covering as a medical doctor, journalist among others. The Ottoman Şehzade Osman Fuad had also joined these officers, granting royal support to the resistance. During the war, Mustafa Kemal Bey, the future founder of the Republic of Turkey, was wounded by shrapnel to his eye.[38] The cost of the war was defrayed chiefly by voluntary offerings from Muslims; men, weapons, ammunition and all kinds of other supplies were constantly sent across to the Egyptian and Tunisian frontiers, not withstanding their neutrality. The Italians occupied Sidi Barrani on the coast between Tobruk and Solum to prevent contraband and troops from entering across the Egyptian frontier, and the naval blockaders guarded the coast as well as capturing several sailing ships laden with contraband.[39]

Italian troops landed at Tobruk after a brief bombardment on 4 December 1911, occupied the seashore, and marched towards the hinterlands facing weak resistance.[40] Small numbers of Ottoman soldiers and Libyan volunteers were later organized by Captain Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. The small 22 December Battle of Tobruk resulted in Mustafa Kemal's victory.[41] With that achievement, he was assigned to Derna War quarters to coordinate the field on 6 March 1912.[citation needed] The Libyan campaign ground to a stalemate by December 1911.[5]

On 3 March 1912, 1,500 Libyan volunteers attacked Italian troops who were building trenches near Derna. The Italians, who were outnumbered but had superior weaponry, held the line. A lack of coordination between the Italian units sent from Derna as reinforcements and the intervention of Ottoman artillery threatened the Italian line, and the Libyans attempted to surround the Italian troops. Further Italian reinforcements, however, stabilised the situation, and the battle ended in the afternoon with an Italian victory.[citation needed]

On 14 September, the Italian command sent three columns of infantry to disband the Arab camp near Derna. The Italian troops occupied a plateau and interrupted Ottoman supply lines. Three days later, the Ottoman commander, Enver Bey, attacked the Italian positions on the plateau. The larger Italian fire drove back the Ottoman soldiers, who were surrounded by a battalion of Alpini and suffered heavy losses. A later Ottoman attack had the same outcome.[citation needed] Then, operations in Cyrenaica ceased until the end of the war.

Although some elements of the local population collaborated with the Italians, counterattacks by Ottoman soldiers with the help of local troops confined the Italian army to the coastal region.[8] In fact, by the end of 1912 the Italians had made little progress in conquering Libya. The Italian soldiers were in effect besieged in seven enclaves on the coasts of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica.[42] The largest was at Tripoli and extended barely 15 kilometers (9.3 miles) from the town.[42]

Naval warfare

At sea, the Italians enjoyed a clear advantage. The Italian Navy had seven times the tonnage of the Ottoman Navy and was better trained.[43]

In January 1912, the Italian cruiser Piemonte, with the Soldato class destroyers Artigliere and Garibaldino, sank seven Ottoman gunboats (Ayintab, Bafra, Gökcedag, Kastamonu, Muha, Ordu and Refahiye) and a yacht (Sipka) in the Battle of Kunfuda Bay. The Italians blockaded the Red Sea ports of the Ottomans and actively supplied and supported the Emirate of Asir, which was also then at war with the Ottoman Empire.[44]

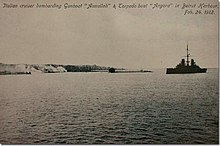

Then, on 24 February, in the Battle of Beirut, two Italian armoured cruisers attacked and sank an Ottoman casemate corvette and six lighters, retreated and returned and then sank an Ottoman torpedo boat. Avnillah alone suffered 58 killed and 108 wounded. By contrast, the Italian ships took no casualties and also no direct hits from any of the Ottoman warships.[45] Italy had feared that the Ottoman naval forces at Beirut could be used to threaten the approach to the Suez Canal. The Ottoman naval presence at Beirut was completely annihilated and casualties on the Ottoman side were heavy. The Italian Navy gained complete naval dominance of the southern Mediterranean for the rest of the war.

Although Italy could extend its control to almost all of the 2,000 km of the Libyan coast between April and early August 1912, its ground forces could not venture beyond the protection of the navy's guns and so were limited to a thin coastal strip. In the summer of 1912, Italy began operations against the Ottoman possessions in the Aegean Sea with the approval of the other powers, which were eager to end a war that was lasting much longer than expected. Italy occupied twelve islands in the sea, comprising the Ottoman province of Rhodes, which then became known as the Dodecanese, but that raised the discontent of Austria-Hungary, which feared that it could fuel the irredentism of nations such as Serbia and Greece and cause imbalance in the already-fragile situation in the Balkan area. The only other relevant military operation of the summer was an attack of five Italian torpedo boats in the Dardanelles on 18 July.

Irregular war and atrocities

With a decree of 5 November 1911, Italy declared its sovereignty over Libya. Although the Italians controlled the coast, many of their troops had been killed in battle and nearly 6,000 Ottoman soldiers remained to face an army of nearly 140,000 Italians. As a result, the Ottomans began using guerrilla tactics. Indeed, some "Young Turk" officers reached Libya and helped organize a guerrilla war with local mujahideen.[46] Many local Libyans joined forces with the Ottomans because of their common faith against the "Christian invaders" and started bloody guerrilla warfare. Italian authorities adopted many repressive measures against the rebels, such as public hangings as retaliation for ambushes.

On 23 October 1911, over 500 Italian soldiers were slaughtered by Turkish troops at Sciara Sciatt, on the outskirts of Tripoli.[47] This massacre occurred, at least in part, reportedly due to the rape and sexual assault of Libyan and Turkish women by the Italian troops.[48] Nevertheless, as a consequence, on the next day the 1911 Tripoli massacre had Italian troops systematically murder thousands of civilians by moving through local homes and gardens one by one, including by setting fire to a mosque with 100 refugees inside.[49] Although Italian authorities attempted to keep the news of the massacre from getting out, the incident soon became internationally known.[49] The Italians started to show photographs of the massacred Italian soldiers at Sciara Sciat to justify their revenge.

Treaty of Ouchy

Italian diplomats decided to take advantage of the situation to obtain a favourable peace deal. On 18 October 1912, Italy and the Ottoman Empire signed a treaty in Ouchy in Lausanne called the First Treaty of Lausanne, which is often also called Treaty of Ouchy to distinguish it from the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, (the Second Treaty of Lausanne).[50][51]

The main provisions of the treaty were as follows:[52]

- The Ottomans would withdraw all military personnel from Trablus and Benghazi vilayets (Libya), but in return, Italy would return Rhodes and the other Aegean islands that it held to the Ottomans.

- Trablus and Benghazi vilayets would have a special status and a naib (regent), and a kadi (judge) would represent the Caliph.

- Before the appointment of the kadis and naibs, the Ottomans would consult the Italian government.

- The Ottoman government would be responsible for the expenses of these kadis and naibs.

Subsequent events prevented the return of the Dodecanese to Turkey, however. The First Balkan War broke out shortly before the treaty had been signed. Turkey was in no position to reoccupy the islands while its main armies were engaged in a bitter struggle to preserve its remaining territories in the Balkans. To avoid a Greek invasion of the islands, it was implicitly agreed on that the Dodecanese would remain under neutral Italian administration until the conclusion of hostilities between the Greeks and the Ottomans, after which the islands would revert to Ottoman rule.

Turkey's continued involvement in the Balkan Wars, followed shortly by World War I (which found Turkey and Italy again on opposing sides), meant that the islands were never returned to the Ottoman Empire. Turkey gave up its claims on the islands in the Treaty of Lausanne, and the Dodecanese continued to be administered by Italy until 1947, when after the Italian defeat in World War II, the islands were ceded to Greece.

Aftermath

The invasion of Libya was a costly enterprise for Italy. Instead of the 30 million lire a month judged sufficient at its beginning, it reached a cost of 80 million a month for a much longer period than was originally estimated.[citation needed] The war cost Italy 1.3 billion lire, nearly a billion more than Giovanni Giolitti estimated before the war.[53] This ruined ten years of fiscal prudence.[53]

After the withdrawal of the Ottoman army the Italians could easily extend their occupation of the country, seizing East Tripolitania, Ghadames, the Djebel and Fezzan with Murzuk during 1913.[54] The outbreak of the First World War with the necessity to bring back the troops to Italy, the proclamation of the Jihad by the Ottomans and the uprising of the Libyans in Tripolitania forced the Italians to abandon all occupied territory and to entrench themselves in Tripoli, Derna, and on the coast of Cyrenaica.[54] The Italian control over much of the interior of Libya remained ineffective until the late 1920s when forces under the Generals Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani waged bloody pacification campaigns. Resistance petered out only after the execution of the rebel leader Omar Mukhtar on 15 September 1931. The result of the Italian colonisation for the Libyan population was that by the mid-1930s it had been cut in half due to emigration, famine, and war casualties. The Libyan population in 1950 was at the same level as in 1911, approximately 1.5 million.[55]

Europe, Balkans and First World War

In 1924, the Serbian diplomat Miroslav Spalajković could look back on the events that led to the First World War and its aftermath and state of the Italian attack, "all subsequent events are nothing more than the evolution of that first aggression."[56] Unlike the British-controlled Egypt, the Ottoman Tripolitania vilayet, which made up modern-day Libya, was core territory of the Empire, like that of the Balkans.[57] The coalition that had defended the Ottomans during the Crimean War (1853–1856), minimised Ottoman territorial losses at the Congress of Berlin (1878) and supported the Ottomans during the Bulgarian Crisis (1885–88) had largely disappeared.[58] The reaction in the Balkans to the Italian declaration of war was immediate. The first draft by Serbia of a military treaty with Bulgaria against Turkey was written by November 1911, with a defensive treaty signed in March 1912 and an offensive treaty signed in May 1912 focused on military action against Ottoman-ruled Southeastern Europe. The series of bilateral treaties between Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro that created the Balkan League was completed in 1912, with the First Balkan War (1912–1913) beginning by a Montenegrin attack on 8 October 1912, ten days before the Treaty of Ouchy.[59] The swift and nearly-complete victory of the Balkan League astonished contemporary observers.[60] However, none of the victors were happy with the division of captured territory, which resulted in the Second Balkan War (1913) in which Serbia, Greece, the Ottomans, and Romania took almost all of the territory that Bulgaria had captured in the first war.[61] In the wake of the enormous change in the regional balance of power, Russia switched its primary allegiance in the region from Bulgaria to Serbia and guaranteed Serbian autonomy from any outside military intervention. The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, by a Serbian nationalist and the resulting Austro-Hungarian plan for military action against Serbia was a major precipitating event of the First World War (1914–1918).

The Italo-Turkish War illustrated to the French and British governments that Italy was more valuable to them inside the Triple Alliance than being formally allied with the Entente. In January 1912, the French diplomat Paul Cambon wrote to Raymond Poincaré that Italy was "more burdensome than useful as an ally. Against Austria, she harbours a latent hostility that nothing can disarm".[62] The tensions within the Triple Alliance would eventually lead Italy to sign the 1915 Treaty of London, which had it abandon the Triple Alliance and join the Entente.[citation needed]

In Italy itself, massive funerals for fallen heroes brought the Catholic Church closer to the government from which it had long been alienated. There emerged a cult of patriotic sacrifice in which the colonial war was celebrated in an aggressive and imperialistic way. The ideology of "crusade" and "martyrdom" characterised the funerals. The result was to consolidate Catholic war culture among devout Italians, which was soon expanded to include Italian involvement in the Great War (1915–1918). That aggressive spirit was revived by the Fascists in the 1920s to strengthen their popular support.[63]

The resistance in Libya was an important experience for the young officers of the Ottoman Army, such as Mustafa Kemal Bey, Enver Bey, Ali Fethi Bey, Cami Bey, Nuri Bey and many others. These young officers were to perform important military duties and accomplishments in the First World War, led the Turkish independency war and found the Republic of Turkey.[64]

Fate of the Dodecanese Islands

Because of the First World War, the Dodecanese remained under Italian military occupation. According to the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, which was never ratified, Italy was supposed to cede all of the islands except Rhodes to Greece in exchange for a vast Italian zone of influence in southwest Anatolia. However, the Greek defeat in the Greco–Turkish War and the foundation of modern Turkey created a new situation that made the enforcement of the terms of that treaty impossible. In Article 15 of the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which superseded the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, Turkey formally recognised the Italian annexation of the Dodecanese. The population was largely Greek, and by treaty in 1947, the islands eventually became part of Greece.[65] As the Dodecanese were part of Italy, the local population was not affected by the subsequent population exchange between Greece and Turkey, and a small community of Dodecanese Turks has remained to this day.

Literature

In his book Primo, the Turkish Child, the Turkish author Ömer Seyfettin tells the fictional story of a boy living in the Ottoman city of Selânik (Salonica, today Thessaloniki), who has to choose his national identity between his Turkish father and Italian mother after the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912 and the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 (Ömer Seyfettin, Primo Türk Çocuğu).[non-primary source needed]

See also

References

- ^ Erik Goldstein (2005). Wars and Peace Treaties: 1816 to 1991. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-1134899128.

- ^ a b Translated and Compiled from the Reports of the Italian General Staff, "The Italo-Turkish War (1911–12)" (Franklin Hudson Publishing Company, 1914), p. 15

- ^ a b The History of the Italian-Turkish War, William Henry Beehler, pp. 13–36

- ^ a b Spencer C. Tucker; Priscilla Mary Roberts. World War I: A Student Encyclopedia. p. 946.

- ^ a b c d Emigrant nation: the making of Italy abroad, Mark I. Choate, Harvard University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-674-02784-1, p. 176.

- ^ Translated and Compiled from the Reports of the Italian General Staff, "The Italo-Turkish War (1911–12)" (Franklin Hudson Publishing Company, 1914), p. 82

- ^ Lyall, Jason (2020). "Divided Armies": Inequality and Battlefield Performance in Modern War. Princeton University Press. p. 278.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Spencer Tucker, Priscilla Mary Roberts: World War I: A Student Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, 2005, ISBN 1-85109-879-8, p. 946.

- ^ "Treaty of Lausanne, October, 1912". www.mtholyoke.edu. Archived from the original on 25 October 2021. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Treaty of Lausanne - World War I Document Archive". wwi.lib.byu.edu. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Jean-Michel Rabaté (2008). 1913: The Cradle of Modernism. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-470-69147-2.

Realizing how easily the Italians had defeated the Ottomans, the members of the Balkan League attacked the empire before the war with Italy was over

- ^ a b Stanton, Andrea L. (2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. Sage. p. 310. ISBN 978-1412981767.

- ^ Maksel, Rebecca. "The World's First Warplane". airspacemag.com. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission: Aviation at the Start of the First World War Archived 2012-10-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James D. Crabtree: On air defense, ISBN 0275947920, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 9

- ^ Wireless telegraphy in the Italo-Turkish War

- ^ A.J.P. Taylor (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe, 1848–1918. Oxford University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0195014082.

- ^ Andrea Ungari (2014). The Libyan War 1911–1912. Cambridge Scholars. p. 117. ISBN 978-1443864923.

- ^ "Alliance System / System of alliances". thecorner.org. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ^ Clark, Christopher M. (2012). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. London: Allen Lane. p. 244. ISBN 978-0713999426. LCCN 2012515665.

- ^ Clark, pp. 244–245

- ^ Clark, pp. 245–246

- ^ Clark, p. 246

- ^ a b Geppert, Mulligan & Rose 2015, p. 42.

- ^ Biddle, Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare, p. 19

- ^ "Karalahana.com: Turkey's Black Sea region (Pontos) history, culture and travel guide". Archived from the original on September 15, 2012.

- ^ İlber Ortaylı, 2012, “ Yakın Tarihin Gerçekleri “ pp. 49–55

- ^ M. Taylan Sorgun, "Bitmeyen Savas", 1972. Memoirs of Halil Pasa

- ^ W. Mitchell. Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, Whitehall Yard, Volume 57, Issue 2. p. 997.

- ^ William James Makin (1935). War Over Ethiopia. p. 227.

- ^ İlber Ortaylı, 2012, “ Yakın Tarihin Gerçekleri “ p. 49

- ^ Borrettt, William C. (1945). Down East: Another Cargo of Tales Told Under The Old Town Clock. Halifax: Imperial Publishing. p. 181.

- ^ Geppert, Mulligan & Rose 2015, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Geppert, Mulligan & Rose 2015, p. 43.

- ^ Crow, Encyclopedia of Armored Cars, p. 104.

- ^ Biddle, Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare, p. 19.

- ^ Hallion Strike From the Sky: The History of Battlefield Air Attack, 1910–1945, p. 11.

- ^ a b İlber Ortaylı, 2012, “ Yakın Tarihin Gerçekleri “ p. 53

- ^ a b c d William Henry Beehler, The History of the Italian-Turkish War, September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912, Engagements At Benghasi And Derna In December 1911 (p. 49)

- ^ "1911–1912 Turco-Italian War and Captain Mustafa Kemal". Ministry of Culture of Turkey, edited by Turkish Armed Forces-Division of History and Strategical Studies, pp. 62–65, Ankara, 1985.

- ^ "1911–1912 Turco-Italian War and Captain Mustafa Kemal". Ministry of Culture of Turkey, edited by Turkish Armed Forces-Division of History and Strategical Studies, pp. 62–65, Ankara, 1985.

- ^ a b Libya: a modern history, John Wright, Taylor & Francis, 1981, ISBN 0-7099-2727-4, p. 28.

- ^ Tucker, Roberts, 2005, p. 945.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (25 March 2018). "The Encyclopedia Britannica: a dictionary of arts, sciences, literature and general information". The Encyclopedia Britannica Co. Retrieved 25 March 2018 – via Google Books.[page needed]

- ^ Beehler, William (1913). The history of the Italian-Turkish War, September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. Annapolis: The Advertiser Republican. p. 58.

awn illah.

- ^ "Arab Thoughts on the Italian Colonial Wars in Libya – Small Wars Journal". smallwarsjournal.com. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ Gerwarth, Robert; Manela, Erez (3 July 2014). Empires at War: 1911–1923. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191006944. Retrieved 25 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Duggan, Christopher (2008). The Force of Destiny: A History of Italy Since 1796. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-618-35367-5.

- ^ a b Geoff Simons (2003). Libya and the West: From Independence to Lockerbie. I.B. Tauris. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-86064-988-2.

- ^ "Treaty of Peace Between Italy and Turkey". The American Journal of International Law. 7 (1): 58–62. 1913. doi:10.2307/2212446. JSTOR 2212446. S2CID 246008658.

- ^ "Treaty of Lausanne, October, 1912". Mount Holyoke College, Program in International Relations. Archived from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2007-07-23.

- ^ "Uşi (Ouchy) Antlaşması" [Treaty of Ouchy] (in Turkish). Bildirmem.com. 31 May 2009. Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ a b Mark I. Choate: Emigrant nation: the making of Italy abroad, Harvard University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-674-02784-1, p. 175.

- ^ a b Bertarelli (1929), p. 206.

- ^ The Libyan Economy: Economic Diversification and International Repositioning, Waniss Otman, Erling Karlberg, p. 13

- ^ Clark, pp. 243–244

- ^ Clark, p. 243

- ^ Clark, p. 250

- ^ Clark, pp. 251–252

- ^ Clark, p. 252

- ^ Clark, pp. 256–258

- ^ Clark, p. 249

- ^ Matteo Caponi, "Liturgie funebri e sacrificio patriottico I riti di suffragio per i caduti nella guerra di Libia (1911–1912)."["Funeral Liturgies and Patriotic Sacrifices: The Rites for the Souls of Those Who Fell in the War of Libya (1911–1912)"] Rivista di storia del cristianesimo 10.2 (2013) 437–459

- ^ İlber Ortaylı, 2012, “ Yakın Tarihin Gerçekleri “ p. 55

- ^ P.J. Carabott, "The Temporary Italian Occupation of the Dodecanese: A Prelude to Permanency," Diplomacy and Statecraft, (1993) 4#2 pp 285–312.

Works cited

- Geppert, Dominik; Mulligan, William; Rose, Andreas, eds. (2015). The Wars before the Great War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107478145.

Further reading

- Askew, William C. Europe and Italy's Acquisition of Libya, 1911–1912 (1942) online Archived 2020-10-08 at the Wayback Machine

- Baldry, John (1976). "al-Yaman and the Turkish occupation 1849–1914". Arabica. 23: 156–196. doi:10.1163/157005876X00227.

- Beehler, William Henry. The history of the Italian-Turkish War, September 29, 1911, to October 18, 1912. (1913; reprint: Harvard University Press, 2008)

- Biddle, Tami Davis, Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Ideas about Strategic Bombing, 1914–1945. Princeton University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-691-12010-2.

- Childs, Timothy W. Italo-Turkish Diplomacy and the War Over Libya, 1911–1912. Brill, Leiden, 1990. ISBN 90-04-09025-8.

- Crow, Duncan, and Icks, Robert J. Encyclopedia of Armored Cars. Chatwell Books, Secaucus, New Jersey, 1976. ISBN 0-89009-058-0.

- Hallion, Richard P. Strike From the Sky: The History of Battlefield Air Attack, 1910–1945. (2nd ed.) University of Alabama Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0817356576.

- Paris, Michael. Winged Warfare. Manchester University Press, New York, 1992, pp. 106–115.

- Stevenson, Charles. A Box of Sand: The Italo-Ottoman War 1911–1912: The First Land, Sea and Air War (2014), a major scholarly study

- Vandervort, Bruce. Wars of imperial conquest in Africa, 1830–1914 (Indiana University Press, 1998)

In other languages

- Bertarelli, L.V. (1929). Guida d'Italia, Vol. XVII (in Italian). Milano: Consociazione Turistica Italiana.

- Maltese, Paolo. "L'impresa di Libia", in Storia Illustrata #167, October 1971.

- "1911–1912 Turco–Italian War and Captain Mustafa Kemal". Ministry of Culture of Turkey, edited by Turkish Armed Forces-Division of History and Strategical Studies, pp. 62–65, Ankara, 1985.

- Schill, Pierre. Réveiller l'archive d'une guerre coloniale. Photographies et écrits de Gaston Chérau, correspondant de guerre lors du conflit italo-turc pour la Libye (1911–1912), éd. Créaphis, 2018. 480 pages and 230 photographs. ISBN 978-2-35428-141-0

- Awaken the archive of a colonial war. Photographs and writings of a French war correspondent during the Italo-Turkish war in Libya (1911–1912). With contributions from art historian Caroline Recher, critic Smaranda Olcèse, writer Mathieu Larnaudie and historian Quentin Deluermoz.

- "Trablusgarp Savaşı Ve 1911–1912 Türk-İtalyan İlişkileri: Tarblusgarp Savaşı'nda Mustafa Kemal Atatürk'le İlgili Bazı Belgeler", Hale Şıvgın, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, 2006, ISBN 978-975-16-0160-5

External links

![]() Media related to Italo-Turkish War at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Italo-Turkish War at Wikimedia Commons

- Antonio De Martino.Tripoli italiana Societa Libraria italiana (Library of Congress). New York, 1911

- Turco-Italian War at Turkey in the First World War website

- Johnston, Alan (2011-05-10). "Libya 1911: How an Italian pilot began the air war era". BBC News Online. Retrieved 10 May 2011.

- Map of Europe Archived 2015-03-16 at the Wayback Machine during Italo-Turkish War at omniatlas.com

- V. I. Lenin, The End of the Italo-Turkish War, September 28, 1912.