Tod Browning

Tod Browning | |

|---|---|

Browning in 1921 | |

| Born | Charles Albert Browning Jr. July 12, 1880 Louisville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 6, 1962 (aged 82) Malibu, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1896–1942 |

Tod Browning (born Charles Albert Browning Jr.; July 12, 1880 – October 6, 1962) was an American film director, film actor, screenwriter, vaudeville performer, and carnival sideshow and circus entertainer. He directed a number of films of various genres between 1915[a] and 1939, but was primarily known for horror films.[1] Browning was often cited in the trade press as "the Edgar Allan Poe of cinema."[2]

Browning's career spanned the silent and sound film eras. He is known as the director of Dracula (1931),[3] Freaks (1932),[4] and his silent film collaborations with Lon Chaney and Priscilla Dean.

Early life

"A non-conformist within his family, the alternative society of the circus shaped his disdain for normal mainstream society... circus life, for Browning, represented a flight from conventional lifestyles and responsibilities, which later manifested itself in a love of liquor, gambling and fast cars." — Film historian Jon Towlson in Diabolique Magazine, November 27, 2017[5]

Charles Albert Browning, Jr., was born in Louisville, Kentucky on July 12, 1880,[6][1] the second son of Charles Albert and Lydia Browning. Charles Albert Sr., "a bricklayer, carpenter and machinist," provided his family with a middle-class and Baptist household. Browning's uncle, the baseball star Pete "Louisville Slugger" Browning saw his sobriquet conferred on the iconic baseball bat. His Browning sought to escape early on." And: "A non-conformist within his family, Browning seems to have taken after his uncle, the baseball player Pete Browning. Like Pete he was alcoholic from a young age (an affliction that would eventually result in Pete being committed to a mental institution)."[7]

Circus, sideshow and vaudeville

Browning was fascinated by circus and carnival life as a child. At the age of 16, and before finishing high school, he ran away from his well-to-do family to join a traveling circus.[8]

Initially hired as a roustabout, he soon began serving as a "spieler" (a barker at sideshows) and by 1901 was performing song and dance routines for Ohio and Mississippi riverboat entertainment, as well as acting as a contortionist for the Manhattan Fair and Carnival Company.[9] Browning developed a live burial act in which he was billed as "The Living Hypnotic Corpse", and performed as a clown with the Ringling Brothers circus. He would later draw on these early experiences to inform his cinematic inventions.[10][11][12]

In 1906, Browning was briefly married to Amy Louis Stevens in Louisville.[13] Adopting the professional name "Tod" Browning (tod is the German word for death),[14] Browning abandoned his wife and became a vaudevillian, touring extensively as both a magician's assistant and a blackface comedian in an act called The Lizard and the Coon with comedian Roy C. Jones. He appeared in a Mutt and Jeff sketch in the 1912 burlesque revue The World of Mirth with comedian Charles Murray.[15]

Film actor: 1909–1913

In 1909, after 13 years performing in carnivals and vaudeville circuits, Browning, age 29, transitioned to film acting.[16]

Browning's work as a comedic film actor began in 1909 when he performed with director and screenwriter Edward Dillon in film shorts. In all, Browning was cast in over 50 of these one- or two-reeler slapstick productions. Film historian Boris Henry observes that "Browning's experience as a slapstick actor [became] incorporated into his career as a filmmaker." Dillon later provided many of the screenplays for the early films that Browning would direct.[17][18] A number of actors that Browning performed with in his early acting career would later appear in his own pictures, many of whom served their apprenticeships with Keystone Cops director Mack Sennett, among them Wallace Beery, Ford Sterling, Polly Moran, Wheeler Oakman, Raymond Griffith, Kalla Pasha, Mae Busch, Wallace MacDonald and Laura La Varnie.[19]

In 1913, Browning was hired by film director D. W. Griffith at Biograph Studios in New York City, first appearing as an undertaker in Scenting a Terrible Crime (1913).[20] Both Griffith and Browning departed Biograph and New York that same year and together joined Reliance-Majestic Studios in Hollywood, California.[21][22] Browning was featured in several Reliance-Majestic films, including The Wild Girl (1917).[23]

Early film directing and screenwriting: 1914–1916

Film historian Vivian Sobchack reports that "a number of one- or two-reelers are attributed to Browning from 1914 to 1916" and biographer Michael Barson credits Browning's directorial debut to the one-reeler drama The Lucky Transfer, released in March 1915.[24]

Browning's career almost ended when, intoxicated, he drove his vehicle into a railroad crossing and collided with a locomotive. Browning suffered grievous injuries, as did passenger George Siegmann. A second passenger, actor Elmer Booth, was killed instantly.[25][26] Film historian Jon Towlson notes that "alcoholism was to contribute to a major trauma in Browning's personal life that would shape his thematic obsessions...After 1915, Browning began to direct his traumatic experience into his work – radically reshaping it in the process."[27] According to biographers David J. Skal and Elias Savada, the tragic event transformed Browning's creative outlook:

A distinct pattern had appeared in his post-accident body of work, distinguishing it from the comedy that had been his specialty before 1915. Now his focus was moralistic melodrama, with recurrent themes of crime, culpability and retribution.[28]

Indeed, the thirty-one films that Browning wrote and directed between 1920 and 1939 were, with few exceptions, melodramas.[29]

Browning's injuries likely precluded a further career as an actor.[30] During his protracted convalescence,[31] Browning turned to writing screenplays for Reliance-Majestic.[32] Upon his recovery, Browning joined Griffith's film crew on the set of Intolerance (1916) as an assistant director and appeared in a bit part for the production's "modern story" sequence.[33][34]

Director: early silent feature films, 1917–1919

In 1917, Browning wrote and directed his first full-length feature film, Jim Bludso, for Fine Arts/ Triangle film companies, starring Wilfred Lucas in the title role. The story is based on a poem by John Hay, a former personal secretary to Abraham Lincoln during the American Civil War.[35][36]

Browning married his second wife Alice Watson in 1917; they would remain together until her death in 1944.[37]

Returning to New York in 1917, Browning directed pictures for Metro Pictures.[38][39] There he made Peggy, the Will O' the Wisp and The Jury of Fate. Both starred Mabel Taliaferro, the latter in a dual role achieved with double exposure techniques that were groundbreaking for the time.[citation needed] Film historian Vivian Sobchack notes that many of these films "involved the disguise and impersonations found in later Browning films." (See Filmography below.)[40] Browning returned to Hollywood in 1918 and produced three more films for Metro, each of which starred Edith Storey: The Eyes of Mystery, The Legion of Death and Revenge, all filmed and released in 1918. These early and profitable five-, six- and seven-reel features Browning made between 1917–1919 established him as "a successful director and script writer."[41][38][42]

In the spring of 1918 Browning departed Metro and signed with Bluebird Photoplays studios (a subsidiary of Carl Laemmle's Universal Pictures), then in 1919 with Universal where he would direct a series of "extremely successful" films starring Priscilla Dean.[43][44]

Universal Studios: 1919–1923

During his tenure at Universal, Browning directed a number of the studio's top female actors, among them Edith Roberts in The Deciding Kiss and Set Free (both 1918) and Mary MacLaren in The Unpainted Woman, A Petal on the Current and Bonnie, Bonnie Lassie, all 1919 productions.[45] Browning's most notable films for Universal, however, starred Priscilla Dean, "Universal's leading lady known for playing 'tough girls'" and with whom he would direct nine features.[46]

The Priscilla Dean films

Browning's first successful Dean picture—a "spectacular melodrama"—is The Virgin of Stamboul (1920). Dean portrays Sari, a "virgin beggar girl" who is desired by the Turkish chieftain Achmet Hamid (Wallace Beery).[47] Browning's handling of the former slapstick comedian Beery as Achmet reveals the actor's comedic legacy and Browning's own roots in burlesque.[48] Film historian Stuart Rosenthal wrote that the Dean vehicles possess "the seemingly authentic atmosphere with which Browning instilled his crime melodramas, adding immeasurably to later efforts like The Black Bird (1926), The Show (1927) and The Unholy Three (1925)."[49]

The Dean films exhibit Browning's fascination with 'exotic' foreign settings and with underworld criminal activities, which serve to drive the action of his films. Dean is cast as a thieving demimonde who infiltrates high society to burgle jewelry in The Exquisite Thief (1919); in Under Two Flags (1922), set in colonial French Algiers, Dean is cast as a French-Arab member of a harem—her sobriquet is "Cigarette—servicing the French Foreign Legion; and in Drifting (1923), with its "compelling" Shanghai, China scenes recreated on the Universal backlot, Dean plays an opium dealer.[50] In Browning's final Dean vehicle at Universal, White Tiger, he indulged his fascination with "quasi-theatrical" productions of illusion—and revealed to movie audiences the mechanisms of these deceptions. In doing so, Browning—a former member of the fraternity of magicians—violated a precept of their professional code.[51]

Perhaps the most fortuitous outcome of the Dean films at Universal is that they introduced Browning to future collaborator Lon Chaney, the actor who would star in Browning's most outstanding films of the silent era. Chaney had already earned the sobriquet "The Man of a Thousand Faces" as early as 1919 for his work at Universal.[52] Universal's vice-president Irving Thalberg paired Browning with Chaney for the first time in The Wicked Darling (1919), a melodrama in which Chaney played the thief "Stoop" Conners who forces a poor girl (Dean) from the slums into a life of crime and prostitution.[53]

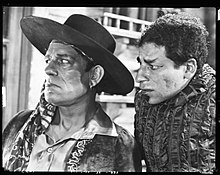

In 1921, Browning and Thalberg enlisted Chaney in another Dean vehicle, Outside the Law, in which he plays the dual roles of the sinister "Black Mike" Sylva and the benevolent Ah Wing. Both of these Universal production exhibit Browning's "natural affinity for the melodramatic and grotesque." In a special effect that drew critical attention, Chaney appears to murder his own dual character counterpart through trick photography[54] and "with Thalberg supporting their imaginative freedom, Chaney's ability and unique presence fanned the flames of Browning's passion for the extraordinary."[55] Biographer Stuart Rosenthal remarks upon the foundations of the Browning-Chaney professional synergy:

In the screen personality of Lon Chaney, Tod Browning found the perfect embodiment of the type of character that interested him... Chaney's unconditional dedication to his acting gave his characters the extraordinary intensity that was absolutely essential to the credibility of Browning's creations.[56]

When Thalberg resigned as vice-president at Universal to serve as production manager with the newly amalgamated Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) in 1925, Browning and Chaney accompanied him.[57]

The Browning-Chaney collaborations at MGM: 1925–1929

After moving to MGM in 1925 under the auspices of production manager Irving Thalberg, Browning and Chaney made eight critically and commercially successful feature films, representing the zenith of both their silent film careers. Browning wrote or co-wrote the stories for six of the eight productions. Screenwriter Waldemar Young, credited on nine of the MGM pictures, worked effectively with Browning.[58][59] At MGM, Browning would reach his artistic maturity as a filmmaker.[60]

The first of these MGM productions established Browning as a talented filmmaker in Hollywood, and deepened Chaney's professional and personal influence on the director: The Unholy Three.[61][62][63]

The Unholy Three (1925)

In a circus tale by author Tod Robbins—a setting familiar to Browning—a trio of criminal ex-carnies and a pickpocket form a jewelry theft ring. Their activities lead to a murder and an attempt to frame an innocent bookkeeper. Two of the criminal quartet reveal their humanity and are redeemed; two perish through violent justice.

The Unholy Three is an outstanding example of Browning's delight in the "bizarre" (though, here, not macabre) melodrama and its "the perverse characterizations" that Browning and Chaney devise anticipate their subsequent collaborations.[64]

Lon Chaney doubles as Professor Echo, a sideshow ventriloquist, and as Mrs. "Granny" O'Grady (a cross-dressing Echo), the mastermind of the gang. Granny/Echo operates a talking parrot pet shop as a front for the operation. Film critic Alfred Eaker notes that Chaney renders "the drag persona with depth of feeling. Chaney never camps it up and delivers a remarkable, multifaceted performance."[65]

Harry Earles, a member of The Doll Family midget performers plays the violent and wicked Tweedledee who poses as Granny's infant grandchild, Little Willie. (Granny conveys the diminutive Willie in a perambulator.)[66]

Victor McLagen is cast as weak-minded Hercules, the circus strongman who constantly seeks to assert his physical primacy over his cohorts. Hercules detests Granny/Echo, but is terrified by the ventriloquist's "pet" gorilla. He doubles as Granny O'Grady's son-in-law and father to Little Willie.[67]

The pickpocket Rosie, played by Mae Busch, is the object of Echo's affection, and they share a mutual admiration as fellow larcenists. She postures as the daughter to Granny/Echo and as the mother of Little Willie.[68][69]

The pet shop employs the diffident bookkeeper, Hector "The Boob" MacDonald (Matt Moore) who is wholly ignorant of the criminal proceedings. Rosie finds this "weak, gentle, upright, hardworking" man attractive.[70][71]

When Granny O'Malley assembles her faux-"family" in her parlor to deceive police investigators, the movie audience knows that "the grandmother is the head of a gang and a ventriloquist, the father a stupid Hercules, the mother a thief, the baby a libidinous, greedy [midget], and the pet...an enormous gorilla." Browning's portrait is a "sarcastic distortion" that subverts a cliched American wholesomeness and serves to deliver "a harsh indictment...of the bourgeois family."[72]

Film historian Stuart Rosenthal identifies "the ability to control another being" as a central theme in The Unholy Three. The deceptive scheme through which the thieves manipulate wealthy clients, demonstrates a control over "the suckers" who are stripped of their wealth, much as circus sideshow patrons are deceived: Professor Echo and his ventriloquist's dummy distract a "hopelessly naive and novelty-loving" audience as pickpocket Rosie relieves them of their wallets.[73][74] Browning ultimately turns the application of "mental control" to serve justice. When bookkeeper Hector takes the stand in court, testifying in his defense against a false charge of murder, the reformed Echo applies his willpower to silence the defendant, and uses his voice throwing power to provide the exonerating testimony. When Hector descends from the stand, he tells his attorney "That wasn't me talking. I didn't say a word." Browning employs a set of dissolves to make the ventriloquists role perfectly clear.[75][76]

Film historian Robin Blyn comments on the significance of Echo's courtroom confession:

Professor Echo's [moral] conversion represents one of the final judgement on the conversion of the cinema of sound attractions to a sound-based narrative cinema disciplined to the demands of realism. Echo's decision to interrupt the proceedings and confess, rather than 'throwing voices' at the judge or the jury, conveys the extent to which the realist mode had become the reigning aesthetic law. Moreover, in refusing his illusionist gift, Echo relinquishes ventriloquism as an outmoded and ineffective art...[77]

With The Unholy Three, Browning provided MGM with a huge box-office and critical success.[78]

The Mystic (1925)

Although fascinated by the grotesque, the deformed and the perverse, Browning (a former magician) was a debunker of the occult and the supernatural...Indeed, Browning is more interested in tricks and illusions than the supernatural. — Film historian Vivian Sobchack in The Films of Tod Browning (2006)[79]

While Lon Chaney was making The Tower of Lies (1925) with director Victor Sjöström Browning wrote and directed an Aileen Pringle vehicle, The Mystic.[80][81] The picture has many of the elements typical of Browning oeuvre at MGM: Carnivals, Hungarian Gypsies and séances provide the exotic mise-en-scene, while the melodramatic plot involves embezzlement and swindling. An American con man Michael Nash (Conway Tearle) develops a moral conscience after falling in love with Pringle's character, Zara, and is consistent with Browning's "themes of reformation and unpunished crimes." and the couple achieve a happy reckoning.[82] Browning, a former sideshow performer, is quick to reveal to his movie audience the illusionist fakery that serves to extract a fortune from a gullible heiress, played by Gladys Hulette.[83]

Dollar Down (1925): Browning followed The Mystic with another "crook melodrama involving swindlers" for Truart productions. Based on a story by Jane Courthope and Ethyl Hill, Dollar Down stars Ruth Roland and Henry B. Walthall.[84][85]

Following these "more conventional" crime films, Browning and Chaney embarked on their final films of the late silent period, "the strangest collaboration between director and actor in cinema history; the premises of the films were outrageous."[86][87]

The Blackbird (1926)

Browning helps to keep the development of The Blackbird taut by employing Chaney's face as an index of the rapidly oscillating mood of the title character. Chaney is the key person who will determine the fates of West End Bertie and Fifi. The plasticity of his facial expressions belies to the audience the spirit of cooperation he offers the young couple...the internal explosiveness monitored in his face is a constant reminder of the danger represented by his presence. — Biographer Stuart Rosenthal in Tod Browning: The Hollywood Professionals, Volume 4 (1975)[88]

Browning and Chaney were reunited in their next feature film, The Blackbird (1926), one of the most "visually arresting" of their collaborations.[89]

Browning introduces Limehouse district gangster Dan Tate (Chaney), alias "The Blackbird", who creates an alter identity, the physically deformed christian missionary "The Bishop." Tate's purported "twin" brother is a persona he uses to periodically evade suspicion by the police under "a phony mantle of christian goodness"—an image utterly at odds with the persona of The Blackbird.[90] According to film historian Stuart Rosenthal, "Tate's masquerade as the Bishop succeeds primarily because the Bishop's face so believably reflects a profound spiritual suffering that is absolutely foreign to the title character [The Blackbird]."[91]

Tate's competitor in crime, the "gentleman-thief" Bertram "West End Bertie" Glade (Owen Moore, becomes romantically involved with a Limehouse cabaret singer, Mademoiselle Fifi Lorraine (Renée Adorée). The jealous Tate attempts to frame Bertie for the murder of a policeman, but is mortally injured in an accident while in the guise of The Bishop. Tate's wife, Polly (Doris Lloyd discovers her husband's dual identity, and honors him by concealing his role as "The Blackbird." The reformed Bertie and his lover Fifi are united in matrimony.[92]

Chaney's adroit "quick-change" transformations from the Blackbird into The Bishop—intrinsic to the methods of "show culture"—are "explicitly revealed" to the movie audience, such that Browning invites them to share in the deception.[93]

Browning introduces a number of slapstick elements into The Blackbird. Doris Lloyd, portrays Tate's ex-wife Limehouse Polly, demonstrating her comic acumen in scenes as a flower girl,[94] and Browning's Limehouse drunkards are "archetypical of burlesque cinema." Film historian Boris Henry points out that "it would not be surprising if the fights that Lon Chaney as Dan Tate mimes between his two characters (The Blackbird and The Bishop) were inspired by actor-director Max Linder's performance in Be My Wife, 1921."[95]

Film historian Stuart Rosenthal identifies Browning's characterization of Dan Tate/the Blackbird as a species of vermin lacking in nobility, a parasitic scavenger that feeds on carrion and is unworthy of sympathy.[96] In death, according to film critic Nicole Brenez, The Blackbird "is deprived of [himself]...death, then, is no longer a beautiful vanishing, but a terrible spiriting away."[97]

Though admired by critics for Chaney's performance, the film was only modestly successful at the box office.[98]

The Road to Mandalay (1926)

Any comprehensive contemporary evaluation of Browning's The Road to Mandalay is problematic. According to Browning biographer Alfred Eaker only a small fraction of the original seven reels exist. A 16 mm version survives in a "fragmented and disintegrated state" discovered in France in the 1980s.[99]

In a story that Browning wrote with screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz ,[85] The Road to Mandalay (not related to author Rudyard Kipling's 1890 poem), is derived from the character "dead-eyed" Singapore Joe (Lon Chaney), a Singapore brothel operator. As Browning himself explained:

The [story] writes itself after I have conceived the characters... the same for The Road to Mandalay. The initial idea was that of a man so frightfully ugly that he was ashamed to reveal himself to his own daughter. In this way one can develop any story.[100]

The picture explores one of Browning's most persistent themes: that of a parent who asserts sexual authority vicariously through their own offspring.[101] As such, an Oedipal narrative is established, "a narrative that dominates Browning's work" and recognized as such by contemporary critics.[102][103]

Joe's daughter, Rosemary (Lois Moran), now a young adult, has been raised in a convent where her father left her as an infant with her uncle, Father James (Henry B. Walthall). Rosemary is ignorant of her parentage; she lives a chaste and penurious existence. Brothel keeper Joe makes furtive visits to the shop where she works as a clerk.[104] His attempts to anomalously befriend the girl are met with revulsion at his freakish appearance. Joe resolves to undergo plastic surgery to achieve a reproachment with his daughter and redeem his sordid history. Father James doubts his brothers' commitment to reform and to reestablish his parenthood. A conflict emerges when Joe's cohorts and rivals in crime, "The Admiral" Herrington (Owen Moore) and English Charlie Wing (Kamiyama Sojin), members of "the black spiders of the Seven Seas" appear on the scene. The Admiral encounters Rosemary at the bazaar where she works and is instantly smitten with her; his genuine resolve to abandon his criminal life wins Rosemary's devotion and a marriage is arranged. When Joe discovers these developments, the full force of his "sexual frustrations" are unleashed. Joe's attempt to thwart his daughter's efforts to escape his control ends when Rosemary stabs her father, mortally wounding him. The denouement is achieved when the dying Joe consents to her marriage and Father James performs the last rites upon his brother.[105]

Film critic Alfred Eaker observes: "The Road to Mandalay is depraved, pop-Freudian, silent melodrama at its ripest. Fortunately, both Browning and Chaney approach this hodgepodge of silliness in dead earnest."[106] Religious imagery commonly appears in Browning's films, "surrounding his characters with religious paraphernalia." Browning, a mason, uses Christian iconography to emphasize Joe's moral alienation from Rosemary.[107] Biographer Stuart Rosenthal writes:

As Singapore Joe gazes longingly at his daughter...the display of crucifixes that [surrounds her] testifies of his love for her while paradoxically acting as a barrier between them.[108]

Rosenthal adds ""Religion for the Browning hero is an additional spring of frustration – another defaulted promise."[109]

As in all of the Browning-Chaney collaborations, The Road to Mandalay was profitable at the box office.[110]

London After Midnight (1927)

Whereas Browning's The Road to Mandalay (1926) exists in a much deteriorated 16 mm abridged version,[111] London After Midnight is no longer believed to exist, the last print destroyed in an MGM vault fire in 1965.[112]

London After Midnight is widely considered by archivists the Holy Grail and "the most sought after and discussed lost film of the silent era."[113] A detailed photo reconstruction, based on stills from the film was assembled by Turner Classic Movies' Rick Schmidlin in 2002.[114]

Based on Browning's own tale entitled "The Hypnotist", London After Midnight is a "drawing room murder mystery'—its macabre and Gothic atmosphere resembling director Robert Wiene's 1920 The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.[115]

Sir Roger Balfour is found dead at the estate of his friend Sir James Hamlin. The gunshot wound to Balfour's head appears self-inflicted. The Scotland Yard inspector and forensic hypnotist in charge, "Professor" Edward C. Burke (Lon Chaney) receives no reports of foul play and the death is deemed a suicide. Five years past, and the estates current occupants are alarmed by a ghoulish, fanged figure wearing a cape and top hat stalking the hallways at night. He is accompanied by a corpse-like female companion. The pair of intruders are the disguised Inspector Burke, masquerading as a vampire (also played by Chaney), and his assistant, "Luna, the Bat Girl" (Edna Tichenor). When the terrified residents call Scotland Yard, Inspector Burke appears and reopens Balfour's case as a homicide. Burke uses his double role to stage a series of elaborate illusions and applications of hypnotism to discover the identity of the murderer among Balfour's former associates.[116][117][118]

Browning's "preposterous" plot is the platform on which he demonstrates the methods of magic and show culture, reproducing the mystifying spectacles of "spirit theater" that purport to operate through the paranormal. Browning's cinematic illusions are conducted strictly through mechanical stage apparatus: no trick photography is employed.[119] "illusion, hypnotism and disguise" are used to mimic the conceits and pretenses of the occult, but primarily for dramatic effect and only to reveal them as tricks.[120]

Mystery stories are tricky, for if they are too gruesome or horrible, if they exceed the average imagination by too much, the audience will laugh. London After Midnight is an example of how to get people to accept ghosts and other supernatural spirits by letting them turn out to be the machinations of a detective. Thereby the audience is not asked to believe the horrible impossible, but the horrible possible, and plausibility increased, rather than lessened, the thrill and chills. — Tod Browning commenting on his cinematic methods in an interview with Joan Dickey for Motion Picture Magazine, March 1928[121][122]

After the murderer is apprehended, Browning's Inspector Burke/The Man in the Beaver Hat reveals the devices and techniques he has used to extract the confession, while systematically disabusing the cast characters—and the movie audience—of any supernatural influence on the foregoing events.[123] Film historians Stefanie Diekmann and Ekkehard Knörer observe succinctly that "All in all, Browning's scenarios [including London After Midnight] appear as a long series of tricks, performed and explained."[124]

Lon Chaney's make-up to create the menacing "Man with the Beaver Hat" is legendary. Biographer Alfred Eaker writes: "Chaney's vampire...is a make-up artist's delight, and an actor's hell. Fishing wire looped around his blackened eye sockets, a set of painfully inserted, shark-like teeth producing a hideous grin, a ludicrous wig under a top hat, and white pancake makeup achieved Chaney's kinky look. To add to the effect Chaney developed a misshapen, incongruous walk for the character."[65]

London After Midnight received a mixed critical response, but delivered handsomely at the box office "grossing over $1,000,000 in 1927 dollars against a budget of $151,666.14."[125]

The Show (1927)

In 1926, while Lon Chaney was busy making Tell It to the Marines with filmmaker George W. Hill, Browning directed The Show, "one of the most bizarre productions to emerge from silent cinema." (The Show anticipates his subsequent feature with Chaney, a "carnival of terror": The Unknown).[126]

Screenwriter Waldemar Young based the scenario on elements from the author Charles Tenny Jackson's The Day of Souls.[127]

The Show is a tour-de-force demonstration of Browning's penchant for the spectacle of carnival sideshow acts combined with the revelatory exposure of the theatrical apparatus and techniques that create these illusions. Film historian Matthew Solomon notes that "this is not specific to his films with Lon Chaney."[128] Indeed, The Show features two of MGM's leading actors: John Gilbert, as the unscrupulous ballyhoo Cock Robin, and Renée Adorée as his tempestuous lover, Salome. Actor Lionel Barrymore plays the homicidal Greek. Romantic infidelities, the pursuit of a small fortune, a murder, attempted murders, Cock Robin's moral redeemtion and his reconciliation with Salome comprise the plot and its "saccarine" ending.[129]

Browning presents a menagerie of circus sideshow novelty acts from the fictitious "Palace of Illusions", including disembodied hands delivering tickets to customers; an illusionary beheading of a biblical figure (Gilbert as John the Baptist); Neptuna (Betty Boyd) Queen of the Mermaids; the sexually untoward Zela (Zalla Zarana) Half-Lady; and Arachnida (Edna Tichenor, the Human Spider perched on her web. Browning ultimately reveals "how the trick is done", explicating the mechanical devices to the film audience – not to the film's carnival patrons.[130]

You see, now he's got the fake sword. — intertitle remark by an onscreen observer of Browning's "detailed reconstruction" of an illusionary theatrical beheading in The Show. — Film historian Matthew Solomon in Staging Deception: Theatrical Illusionism in Browning's Films of the 1920s (2006)[131]

The central dramatic event of The Show derives from another literary work, a "magic playlet" by Oscar Wilde entitled Salomé (1896). Browning devises an elaborate and "carefully choreographed" sideshow reenactment of Jokanaan's biblical beheading (played by Gilbert), with Adorée as Salomé presiding over the lurid decapitation, symbolic of sadomasochism and castration.[132]

The Show received generally good reviews, but approval was muted due to Gilbert's unsavory character, Cock Robin. Browning was now poised to make his masterwork of the silent era, The Unknown (1927).[133][134][135]

The Unknown (1927): A silent era chef d'oeuvre

The Unknown marks the creative apogee of the Tod Browning and Lon Chaney collaborations, and is widely considered their most outstanding work of the silent era.[136] More so than any of Browning's silent pictures, he fully realizes one of his central themes in The Unknown: the linkage of physical deformity with sexual frustration.[137]

[The story] writes itself after I have conceived the characters. The Unknown came to me after I had the idea of a man [Alonzo] without arms. I then asked myself what are the most amazing situations and actions that a man thus reduced could be involved... — Tod Browning in Motion Picture Classic interview, 1928[138][139]

I contrived to make myself look like an armless man, not simply to shock and horrify you but merely to bring to the screen a dramatic story of an armless man. — Actor Lon Chaney, on his creation of the character Alonzo in The Unknown.[140]

Circus performer "Alonzo the armless", a Gypsy knife-thrower, appears as a double amputee, casting his knives with his feet. His deformity is an illusion (except for a bifid thumb), achieved by donning a corset to bind and conceal his healthy arms. The able-bodied Alonzo, sought by the police, engages in this deception to evade detection and arrest.[141] Alonzo harbors a secret love for Nanon (Joan Crawford), his assistant in the act. Nanon's father is the abusive (perhaps sexually so) ringmaster Zanzi (Nick De Ruiz), and Nanon has developed a pathological aversion to any man's embrace. Her emotional dysfunction precludes any sexual intimacy with the highly virile strong-man, Malabar, or Alonzo, his own sexual prowess symbolized by his knife-throwing expertise and his double thumb.[142][143] When Alonzo murders Zanzi during an argument, the homicide is witnessed by Nanon, who detects only the bifid thumb of her father's assailant.[144][145]

Browning's theme of sexual frustration and physical mutilation ultimately manifests itself in Alonzo's act of symbolic castration; he willingly has his arms amputated by an unlicensed surgeon so as to make himself unthreatening to Nanon (and to eliminate the incriminating bifid thumb), so as to win her affection. The "nightmarish irony" of Alonzo's sacrifice is the most outrageous of Browning's plot conceits and consistent with his obsessive examination of "sexual frustration and emasculation".[146][147] When Alonzo recovers from his surgery, he returns to the circus to find that Nanon has overcome her sexual aversions and married the strongman Malabar (Norman Kerry).[148] The primal ferocity of Alonzo's reaction to Nanon's betrayal in marrying Malabar is instinctual. Film historian Stuart Rosenthal writes:

The reversion to an animalistic state in Browning's cinema functions as a way of acquiring raw power to be used as a means of sexual assertion. The incident that prompts the regression [to an animal state] and a search for vengeance is, in almost every case, sexual in nature.[149]

Alonzo's efforts at retribution lead to his own horrific death in a "Grand Guignol finale".[150][151][152]

The Unknown is widely regarded as the most outstanding of the Browning-Chaney collaborations and a masterpiece of the late silent film era.[153] Film critic Scott Brogan regards The Unknown worthy of "cult status."[154]

The Big City (1928)

A lost film, The Big City stars Lon Chaney, Marceline Day and Betty Compson, the latter in her only appearance in an MGM film.[155] Browning wrote the story and Waldemar Young the screenplay concerning "A gangster Lon Chaney who uses a costume jewelry store as a front for his jewel theft operation. After a conflict with a rival gang, he and his girlfriend Marceline Day reform."[156]

Film historian Vivian Sobchack remarked that "The Big City concerns a nightclub robbery, again, the rivalry between two thieves. This time Chaney plays only one of them—without a twisted limb or any facial disguise.'"[157] Critic Stuart Rosenthal commented on The Big City: "...Chaney, without makeup, in a characteristic gangster role."[158]

The Big City garnered MGM $387,000 in profits.[159]

West of Zanzibar (1928)

In West of Zanzibar Browning bares his carnival showman background not to betray himself as an aesthetic primitive, but to display his complete comprehension of the presentational mode, and of the film frame as proscenium...Browning remains neglected because most of the available English-language writing on his films focuses on the thematic singularities of his oeuvre, to the near-exclusion of any analysis of his aesthetic strategies. — Film critic Brian Darr in Senses of Cinema (July 2010)[160]

In 1928, Browning and Lon Chaney embarked upon their penultimate collaboration, West of Zanzibar, based on Chester M. De Vonde play Kongo (1926).[161] scenario by Elliott J. Clawson and Waldemar Young, provided Chaney with dual characterizations: the magician Pharos, and the later paraplegic Pharos who is nicknamed "Dead Legs."[162] A variation of the "unknown parentage motif" Browning dramatizes a complex tale of "obsessive revenge" and "psychological horror."[163] Biographer Stuart Rosenthal made these observations on Chaney's portrayals:

Dead Legs is one of the ugliest and most incorrigible of Browning's heroes...Chaney demonstrated great sensitivity to the feelings and drives of the outcasts Browning devised for him to play. Browning may well be the only filmmaker who saw Chaney as more than an attention-getting gimmick. While many of Chaney's films for other directors involve tales of retribution, only in the Browning vehicles is he endowed with substantial human complexity.[164]

The story opens in Paris, where Pharos, a magician,[165] is cuckolded by his wife Anna (Jacqueline Gadsden) and her lover Crane (Lionel Barrymore). Pharos is crippled when Crane pushes him from a balcony, leaving him a paraplegic. Anna and Crane abscond to Africa. After a year, Phroso learns that Anna has returned. He finds his wife dead in a church, with an infant daughter beside her. He swears to avenge himself both on Crane and the child he assumes was sired by Crane. Unbeknownst to Phroso, the child is actually his.[166] Rosenthal singles out this scene for special mention:

The religious symbolism that turns up periodically in Browning's pictures serves two antagonistic ends. When Dead Legs discovers his dead wife and her child on the pulpit of the cathedral, the solemn surrounding lend a tone of fanatical irrevocability to his vow to make "Crane and his brat pay." At the same time, Chaney's difficult and painful movements upon his belly at the front of the church have the look of a savage parody of a religious supplicant whose faith has been rendered a mockery. God's justice having failed, Dead Legs is about to embark upon his mission of righteousness.[109]

Eighteen years hence, the crippled Pharos, now dubbed Dead Legs, operates an African trading outpost. He secretly preys upon Crane's ivory operations employing local tribes and using sideshow tricks and illusions to seize the goods.[167] After years of anticipation, Dead Legs prepares to hatch his "macabre revenge": a sinister double murder. He summons Anna's daughter Maizie (Mary Nolan) from the sordid brothel and gin mill where he has left her to be raised. He also invites Crane to visit his outpost so as to expose the identity of the culprit stealing his ivory. Dead Legs has arranged to have Crane murdered, but not before informing him that he will invoke the local Death Code, which stipulates that "a man's demise be followed by the death of his wife or child."[168] Crane mockingly disabuses Dead Legs of his gross misapprehension: Maizie is Dead Legs' daughter, not his, a child that Pharos conceived with Anna in Paris. Crane is killed before Dead Legs can absorb the significance of this news.

The climax of the film involves Dead Legs' struggle to save his own offspring from the customary death sentence that his own deadly scheme has set in motion. Dead Legs ultimately suffers the consequences of his "horribly misdirected revenge ploy."[169] The redemptive element with which Browning-Chaney endows Pharos/Dead Legs fate is noted by Rosenthal: "West of Zanzibar reaches the peak of its psychological horror when Chaney discovers that the girl he is using as a pawn in his revenge scheme is his own daughter. Dead Legs undertook his mission of revenge with complete confidence in the righteousness of his cause. Now he is suddenly overwhelmed by the realization of his own guilt. That Barrymore as Crane committed the original transgression in no way diminishes that guilt."[170]

A Browning hero would never feel a compulsion to symbolically relive a moment of humiliation. Instead of taking the philosophical route of subjugating himself to his frustration, Browning's Chaney opts for the primitive satisfaction of striking back, of converting his emotional upheaval into a source of primal strength. The viewer, empathizing with the protagonist, is shocked at the realization of his own potential for harnessing the power of his sense of outrage. This is one of the reasons why West of Zanzibar, and Chaney's other Browning films are so much more disturbing than the horror mysteries he made with other directors. — Stuart Rosenthal in Tod Browning: The Hollywood Professionals, Volume 4 (1975)[171]

Dead Legs' physical deformity reduces him to crawling on the ground, and thus to the "state of an animal."[172] Browning's camera placement accentuates his snake-like "slithering" and establishes "his animal transformation by suddenly changing the visual frame of reference to one that puts the viewer on the same level as the beast on the screen, thereby making him vulnerable to it, accomplished by tilting the camera up at floor level in front of the moving subject [used to] accentuate Chaney's [Dead Legs] slithering movements in West of Zanzibar."[173] Film historians Stephanie Diekmann and Ekkehard Knörer state more generally "...the spectator in Browning's films can never remain a voyeur; or rather, he is never safe in his voyeuristic position..."[174]

Diekmann and Knörer also place West of Zanzibar in the within the realm of the Grand Guignol tradition:

As far as plots are concerned, the proximity of Tod Browning's cinema to the theater of the Grand Guignol is evident...From the castrating mutilation of The Unholy Three (1925) to the sadistic cruelty and bestial brutality intermingled with the orientalising chinoiserie of Where East Is East (1929); from the horribly misdirected revenge ploy of West of Zanzibar (1928); to the no less horribly successful revenge plot of Freaks (1932); from the double-crossing gunplay of The Mystic to the erotically charged twists and turns of The Show: on the level of plot alone, all these are close in spirit and explicitness to Andre de Lorde's theatre of fear and horror.[169]

Despite being characterized as a "cess-pool" by the censorious Harrison's Reports motion picture trade journal, West of Zanzibar enjoyed popular success at the box office.[175]

Where East Is East (1929)

Adapted by Waldemar Young from a story by Browning and Harry Sinclair Drago, Where East Is East borrows its title from the opening and closing verses of Rudyard Kipling's 1889 poem "The Ballad of East and West": "Oh! East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet..."[176] Browning's appropriation of the term "Where East Is East" is both ironic and subversive with regard to his simultaneous cinematic presentation of Eurocentric cliches of the "East" (common in early 20th century advertising, literature and film), and his exposure of these memes as myths.[177] Film historian Stefan Brandt writes that this verse was commonly invoked by Western observers to reinforce conceptions stressing "the homogeneity and internal consistency of 'The East'" and points out that Kipling (born and raised in Bombay, India) was "far from being one-dimensional" when his literary work "dismantles the myth of ethnic essentiality":[178]

Browning's Where East Is East...playfully reenacts the symbolic dimension contained in Kipling's phrase. The expression not only emerges in the movie's title; the vision of the East that is negotiated and shown in all its absurdity here is very much akin to that associated with Kipling.[179]

Biographer Bernd Herzogenrath adds that "paradoxically, the film both essentializes the East as a universal and homogeneous entity ("Where East Is East") and deconstructs it as a Western myth consisting of nothing but colorful [male] fantasies." [brackets and parentheses in original][180]

The last of Browning-Chaney collaborations with an "outrageous premise"[181] and their final silent era film, Where East Is East was marketed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer "as a colonial drama in the mold of British imperialist fiction."[182]

Where East Is East, set in the "picturesque French Indo-China of the 1920s"[183] concerns the efforts of big game trapper "Tiger" Haynes (Chaney) intervention to stop his beloved half-Chinese daughter Toyo (Lupe Velez) from marrying Bobby "white boy" Bailey, a Western suitor and son of a circus owner. He relents when Bobby rescues Toyo from an escaped tiger. The Asian seductress, Madame de Sylva (Estelle Taylor), Tiger's former wife and mother to Toyo—who abandoned her infant to be raised by Tiger—returns to lure Bobby from Toyo and ruin the couple's plans for conjugal bliss.[184][185] Tiger takes drastic action, unleashing a gorilla which dispatches Madame de Sylva but mortally wounds Tiger. He lives long enough witness the marriage of Toyo and Bobby.[186][187]

At first glance, Browning's Where East Is East seems to deploy many of the well-known stereotypes concerning the Orient that were familiar from [Hollywood] productions of the 1910s and 1920s.— above all, in the notion of the East as fundamentally different and unique. At the same time the concept that 'East is East' is satirized through the staging of the Orient as an assortment of costumes and gestures. The conjunction 'where' [in the movie's title] hints at the fictional dimension that the East accrued through Hollywood films. In Browning's ironic use of Kipling's phrase, it is, above all, this constructed world of cinematic fiction that harbors the myth of the East... it is only there that 'East is East.' — Film historian Stefan Brandt in White Bo[d]y in Wonderland: Cultural Alterity and Sexual Desire in Where East Is East (2006)[188]

In a key sequence in which the American Bobby Bailey (Lloyd Hughes), nicknamed "white boy", is briefly seduced by the Asian Madame de Sylva (mother to Bobby's fiancee Toya), Browning offers a cliche-ridden intertitle exchange that is belied by his cinematic treatment. Film historian Stefan Brandt writes: "Browning here plays with the ambiguities involved in the common misreading of Kipling's poem, encouraging his American audience to question the existing patterns of colonial discourse and come to conclusions that go beyond that mode of thinking. The romantic version of the Orient as a land of eternal mysticism is exposed here as a Eurocentric illusion that we must not fall prey to."[189]

Browning's presentation of the alluring Madame de Sylva -whose French title diverges from her Asian origins- introduces one of Browning's primary themes: Reality vs. Appearance. Rosenthal notes that "physical beauty masking perversity is identical to the usual Browning premise of respectability covering corruption. This is the formula used in Where East Is East. Tiger's thorny face masks a wealth of kindness, sensitively and abiding paternal love. But behind the exotic beauty of Madame de Silva lies an unctuous, sinister manner and callous spitefulness."[190]

The animal imagery with which Browning invests Where East Is East informed Lon Chaney's characterization of Tiger Haynes, the name alone identifying him as both "tiger hunter and the tiger himself."[191] Biographer Stuart Rosenthal comments on the Browning-Chaney characterization of Tiger Haynes:

Tiger's bitterness in Where East is East is the result of disgust for Madame de Silva's past and present treachery. [Tiger Haynes] is striving desperately to overcome [his] inner embarrassment and, by revenging himself, re-establish his personal feelings of sexual dominance.[192]

As in Browning's The Unknown (1927) in which protagonist Alonzo is trampled to death by a horse, "animals become the agents of destruction for Tiger [Haynes] in Where East Is East."[193]

Sound films: 1929–1939

Upon completing Where East Is East, MGM prepared to make his first sound production, The Thirteenth Chair (1929). The question as to Browning's adaptability to the film industry's ineluctable transition to sound technology is disputed among film historians.[194]

Biographers David Skal and Elias Savada report that Browning "had made his fortune as a silent film director but had considerable difficulties in adapting his talents to talking pictures."[195] Film critic Vivian Sobchack notes that Browning, in both his silent and sound creations, "starts with the visual rather than the narrative" and cites director Edgar G. Ulmer: "until the end of his career, Browning tried to avoid using dialogue; he wanted to obtain visual effects."[196] Biographer Jon Towlson argues that Browning's 1932 Freaks reveals "a director in full control of the [sound] medium, able to use the camera to reveal a rich subtext beneath the dialogue" and at odds with the general assessment of the filmmakers post-silent era pictures.[197]

Browning's sound oeuvre consists of nine features before his retirement from filmmaking in 1939.[198]

The Thirteenth Chair (1929)

Browning's first sound film, The Thirteenth Chair is based on a 1916 "drawing room murder mystery" stage play of the same title by Bayard Veiller first adapted to film in a 1919 silent version and later a sound remake in 1937.[199]

Set in Calcutta, the story concerns two homicides committed at séances. Illusion and deception are employed to expose the murderer.[200]

In a cast featuring some of MGM's top contract players including Conrad Nagel, Leila Hyams and Margaret Wycherly[201] Hungarian-American Bela Lugosi, a veteran of silent films and the star of Broadway's Dracula (1924) was enlisted by Browning to play Inspector Delzante, when Lon Chaney declined to yet embark on a talking picture.[202][203]

The first of his three collaborations with Lugosi, Browning's handling of the actor's role as Delzante anticipated the part of Count Dracula in his Dracula (1931).[204] Browning endows Lugosi's Delzante with bizarre eccentricities, including a guttural, broken English and heavily accented eyebrows, characteristics that Lugosi made famous in his film roles as vampires.[205] Film historian Alfred Eaker remarks: "Serious awkwardness mars this film, a product from that transitional period from silent to the new, imposing medium of sound. Because of that awkwardness The Thirteenth Chair is not Browning in best form."[65]

Outside the Law (1930)

A remake of Browning's 1921 silent version starred Priscilla Dean and Lon Chaney who appeared in dual roles. Outside the Law concerns a criminal rivalry among gangsters. It stars Edward G. Robinson as Cobra Collins and Mary Nolan as his moll Connie Madden. Film critic Alfred Eaker commented that Browning's remake "received comparatively poor reviews."[206][207]

Dracula (1931): The first talkie horror picture

"I am Dracula". – Bela Lugosi's iconic introduction as the vampire Count Dracula[208]

Browning's Dracula initiated the modern horror genre, and it remains his only "one true horror film."[209] Today the picture stands as the first of Browning's two sound era masterpieces, rivaled only by his Freaks (1932).[210] The picture set in motion Universal Studios' highly lucrative production of vampire and monster movies during the 1930s.[211] Browning approached Universal's Carl Laemmle Jr. in 1930 to organize a film version of Bram Stoker's 1897 gothic horror novel Dracula, previously adapted to film by director F. W. Murnau in 1922.[212]

In an effort to avoid copyright infringement lawsuits, Universal opted to base the film on Hamilton Deane's and Louis Bromfield's melodramatic stage version Dracula (1924), rather than Stoker's novel.[213][214]

Actor Lon Chaney, then completing his first sound film with director Jack Conway in a remake of Browning's silent The Unholy Three (1925), was tapped for the role of Count Dracula.[215] Terminally ill from lung cancer, Chaney entered negotiations for the project. The actor died a few short weeks before shooting was set to commence on Dracula — a significant personal and professional loss to long-time collaborator Browning.[216] Hungarian expatriate and actor Bela Ferenc Deszo Blasco, appearing under the stage name Bela Lugosi, had successfully performed the role of Count Dracula in the American productions of the play for three years.[217] According to film historian David Thomson, "when Chaney died, it was taken for granted that Lugosi would have the role in the film."[218]

The most awesome powers of control belong to the vampires, and Browning's attitude toward these undead poses a particularly intriguing problem. The vampires depend, for support, upon the infirm and innocent elements of society the Browning scorns. They sustain themselves through the blood of the weak...but they are vulnerable to those with the determination to resist them. – Stuart Rosenthal in Tod Browning: The Hollywood Professionals, Volume 4 (1975)[219]

Lugosi's portrayal of Count Dracula is inextricably linked to the vampire genre established by Browning. As film critic Elizabeth Bronfen observes, "the notoriety of Browning's Dracula within film history resides above all else in the uncanny identification between Bela Lugosi and his role."[220] Browning quickly establishes what would become Dracula's— and Bela Lugosi's—sine qua non: "The camera repeatedly focuses on Dracula's hypnotic gaze, which, along with his idiosyncratic articulation, was to become his cinematic trademark."[221] Film historian Alec Charles observes that "The first time we see Bela Lugosi in Tod Browning's Dracula...he looks almost directly into the camera...Browning affords the audience the first of those famously intense and direct into-the-camera Lugosi looks, a style of gaze that would be duplicated time and again by the likes of Christopher Lee and Lugosi's lesser imitators..."[222] Lugosi embraced his screen persona as the preeminent "aristocratic Eastern European vampire" and welcomed his typecasting, assuring his "artistic legacy".[223]

Film critic Elizabeth Bronfen reports that Browning's cinematic interpretation of the script has been widely criticized by film scholars. Browning is cited for failing to provide adequate "montage or shot/reverse shots", the "incoherence of the narrative" and his putative poor handling of the "implausible dialogue" reminiscent of "filmed theatre." Bronfen further notes critic's complaints that Browning failed to visually record the iconic vampiric catalog: puncture wounds on a victims necks, the imbibing of fresh blood, a stake penetrating the heart of Count Dracula. Moreover, no "transformation scenes" are visualized in which the undead or vampires morph into wolves or bats.[224]

Film critics have attributed these "alleged faults" to Browning's lack of enthusiasm for the project. Actor Helen Chandler, who plays Dracula's mistress, Mina Seward, commented that Browning seemed disengaged during shooting, and left the direction to cinematographer Karl Freund.[225]

Bronfen emphasizes the "financial constraints" imposed by Universal executives, strictly limiting authorization for special effects or complex technical shots, and favoring a static camera requiring Browning to "shoot in sequence" in order to improve efficiency.[226] Bronfen suggests that Browning's own thematic concerns may have prompted him—in this, 'the first talkie horror picture'—to privilege the spoken word over visual tricks.":

Browning's concern was always with the bizarre desires of those on the social and cultural margins. It is enough for him to render their fantasies as scenic fragments, which require neither a coherent, nor a sensational story line... the theatricality of his filmic rendition emphasizes both the power of suggestion emanating from Count Dracula's hypnotic gaze and Professor Van Helsing's will power, as well as the seduction transmitted by foregrounding the voices of the marginal and monstrous... even the choice of a static camera seems logical, once one sees it as an attempt to savour the newly discovered possibilities of sound as a medium of seductive film horror.[227]

The scenario follows the vampire Count Dracula to England where he preys upon members of the British upper-middle class, but is confronted by nemesis Professor Van Helsing, (Edward Van Sloan) who possesses sufficient will power and knowledge of vampirism to defeat Count Dracula.[228] Film historian Stuart Rosenthal remarks that "the Browning version of Dracula retains the Victorian formality of the original source in the relationships among the normal characters. In this atmosphere the seething, unstoppable evil personified by the Count is a materialization of Victorian morality's greatest dread."[229]

A number of sequences in Dracula have earned special mention, despite criticism concerning the "static and stagy quality of the film."[230] The dramatic and sinister opening sequence in which the young solicitor Renfield (Dwight Frye) is conveyed in a coach to Count Dracula's Transylvanian castle is one of the most discussed and praised of the picture. Karl Freund's Expressionistic technique is largely credited with its success.[231]

Browning employs "a favorite device" with an animal montage early in the film to establish a metaphoric equivalence between the emergence of the vampires from their crypts and the small parasitic vermin that infest the castle: spiders, wasps and rats.[232] Unlike Browning's previous films, Dracula is not a "long series of [illusionist] tricks, performed and explained"[174] but rather an application of cinematic effects "presenting vampirism as scientifically verified 'reality'."[233]

Despite Universal executives editing out portions of Browning's film, Dracula was enormously successful.[234] Opening at New York City's Roxy Theatre, Dracula earned $50,000 in 48 hours, and was Universal's most lucrative film of the Depression Era.[235] Five years after its release, it had grossed over one million dollars worldwide.[213] Film critic Dennis Harvey writes: "Dracula's enormous popularity fast-tracked Browning's return to MGM, under highly favorable financial terms and the protection of longtime ally, production chief Irving Thalberg."[236][237]

Iron Man (1931)

The last of Browning's three sound films he directed for Universal Studios, Iron Man (1931) is largely ignored in critical literature.[238][239]

Described as "a cautionary tale about the boxer as a physically powerful man brought down by a woman",[240] Browning's boxing story lacks the macabre elements that typically dominate his cinema.[241] Film historian Vivian Sobchack observes that "Iron Man, in subject and plot, is generally regarded as uncharacteristic of Browning's other work."[84] Thematically, however, the picture exhibits a continuity consistent with his obsessive interest in "situations of moral and sexual frustration."[242][243]

Film critic Leger Grindon cites the four "subsidiary motifs" recognized by Browning biographer Stuart Rosenthal: "appearances hiding truth (particularly physical beauty as a mask for villainy), sexual frustration, opposing tendencies within a protagonist that are often projected onto alter egos and finally, an inability to assign guilt." These themes are evident in Iron Man.[244][245]

Actor Lew Ayres, following his screen debut in Universal's immensely successful anti-war themed All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), plays Kid Mason, a Lightweight boxing champion. This sports-drama concerns the struggle between the Kid's friend and manager George Regan Robert Armstrong, and the boxer's adulterous wife Rose (Jean Harlow) to prevail in a contest for his affection and loyalty.[246]

Rather than relying largely upon "editing and composition as expressive tools" Browning moved away from a stationary camera "toward a conspicuous use of camera movement" under the influence of Karl Freund, cinematographer on the 1931 Dracula. Iron Man exhibits this "transformation" in Browning's cinematic style as he entered the sound era.[247] Leger Grindon provides this assessment of Browning's last picture for Universal:

Iron Man is not an anomaly in Tod Browning's career; rather, it is a work that testifies to the continuity of his thematic concerns, as well as showcasing his growing facility with the camera after his work with [cameraman] Karl Fruend...[248]

Though box office earnings for Iron Man are unavailable, a measure of its success is indicated in the two remakes the film inspired: Some Blondes Are Dangerous (1937) and Iron Man (1950).[240]

Browning returned to MGM after completing Iron Man to embark upon the most controversial film of his career: Freaks (1932).[249][250]

Magnum opus: Freaks (1932)

Freaks may be one of the most compassionate movies ever made. – Film critic Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema: Directors and Directions, 1929–1968 (1968) p. 229

Not even the most morbidly inclined could possibly find this picture to their liking. Saying it is horrible is putting it mildly. It is revolting to the extent of turning one's stomach...Anyone who considers this [to be] entertainment should be placed in the pathological ward in some hospital. — Harrison's Reports, 16 July 1932[251]

If Freaks has caused a furor in certain censor circles, the fault lies in the manner in which it was campaigned to the public. I found it to be an interesting and entertaining picture, and I did not have nightmares, nor did I attempt to murder any of my relatives. — Motion Picture Herald, 23 July 1932[251]

After the spectacular success of Dracula (1931) at Universal, Browning returned to MGM, lured by a generous contract and enjoying the auspices of production manager Irving Thalberg.[252] Anticipating a repeat of his recent success at Universal, Thalberg accepted Browning's story proposal based on Tod Robbins' circus-themed tale "Spurs" (1926).[253]

The studio purchased the rights and enlisted screenwriter Willis Goldbeck and Leon Gordon to develop the script with Browning.[254] Thalberg collaborated closely with the director on pre-production, but Browning completed all the actual shooting on the film without interference from studio executives.[255] Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's president, Louis B. Mayer, registered his disgust with the project from its inception and during the filming, but Thalberg successfully intervened on Browning's behalf to proceed with the film.[256] The picture that emerged was Browning's "most notorious and bizarre melodrama."[257]

A "morality play", Freaks centers around the cruel seduction of a circus sideshow midget Hans (Harry Earles) by a statuesque trapeze artist Cleopatra (Olga Baclanova). She and her lover, strongman Hercules (Henry Victor), scheme to murder the diminutive Hans for his inheritance money after sexually humiliating him. The community of freaks mobilizes in Hans' defense, meting out severe justice to Cleopatra and Hercules: the former trapeze beauty is surgically transformed into a sideshow freak. [258]

Browning enlisted a cast of performers largely assembled from carnival freak shows—a community and milieu both of which the director was intimately familiar. The circus freaks serve as dramatic and comedic players, central to the story's development, and do not appear in their respective sideshow routines as novelties.[259][260]

Two major themes in Browning's work—"Sexual Frustration" and "Reality vs. Appearances"—emerge in Freaks from the conflict inherent in the physical incompatibility between Cleopatra and Hans.[261] The guileless Hans' self-delusional fantasy of winning the affection of Cleopatra—"seductive, mature, cunning and self-assured"—provokes her contempt, eliciting "cruel sexual jests" at odds with her attractive physical charms.[262] Browning provides the moral rationale for the final reckoning with Cleopatra before she has discovered Hans' fortune and plans to murder him. Film historian Stuart Rosenthal explains:

It is here that Browning justifies the disruption of an individual's sexual equanimity as a cause for retaliation. Cleopatra's decision to wed the dwarf for his wealth and then dispose of him is not, in itself, a significant advance in villainy...her most heinous crime is committed when she teases Hans by provocatively dropping her cape to the floor, then gleefully kneels to allow her victim to replace it upon her shoulders...This kind of exploitation appears more obscene by far than the fairly clean act of homicide.[67]

Browning addresses another theme fundamental to his work: "Inability to Assign Guilt". The community of freaks delay judgement on Cleopatra when she insults Frieda (Daisy Earles), the midget performer who loves Hans.[263] Their social solidarity cautions restraint, but when the assault on Hans becomes egregious, they act single-mindedly to punish the offender. Browning exonerates the freaks of any guilt: they are "totally justified" in their act of retribution.[264] Stuart Rosenthal describes this doctrine, the "crux" of Browning's social ideal:

Freaks is the film that is most explicit about the closeness of equability and retribution. The freaks live by a simple and unequivocal code that one imagines might be the crux of Browning's ideal for society: 'Offend one of them, and offend them all'...if anyone attempts to harm or take advantage of one of their number, the entire colony responds quickly and surely to mete out appropriate punishment.[265]

Browning cinematic style in Freaks is informed by the precepts of German Expressionism, combining a subdued documentary-like realism with "chiaroscuro shadow" for dramatic effect.[266]

The wedding banquet sequence in which Cleopatra and Hercules brutally degrade Hans is "among the most discussed moments of Freaks" and according to biographer Vivian Sobchack "a masterpiece of sound and image, and utterly unique in conception and realization."[267][268]

The final sequence in which the freaks carry out their "shocking" revenge and Cleopatra's fate is revealed "achieves the most sustained level of high-pitched terror of any Browning picture."[269]

Freaks was given general release only after Thalberg excised 30 minutes of footage deemed offensive to the public.[270] Though Browning had a long history of making profitable pictures at MGM, Freaks was a "disaster" at the box office, though earning mixed reviews among critics.

Browning's reputation as a reliable filmmaker among the Hollywood establishment was tarnished, and he completed only four more pictures before retiring from the industry after 1939. According to biographer Alfred Eaker, "Freaks, in effect, ended Browning's career."[271][272]

Fast Workers (1933)

In the aftermath of the commercial failure of his 1932 Freaks, Browning was assigned to produce and direct (uncredited) an adaptation of John McDermott's play Rivets.[273]

The script for Fast Workers by Karl Brown and Laurence Stallings dramatizes the mutual infidelities, often humorous, that plague a ménage à trois comprising a high-rise construction worker and seducer Gunner Smith (John Gilbert), his co-worker and sidekick, Bucker Reilly (Robert Armstrong) and Mary (Mae Clarke), an attractive "Gold digger" seeking financial and emotional stability during the Great Depression.[274] Browning brings to bear all the thematic modes that typically motivate his characters.[275] Film historian Stuart Rosenthal writes:

In Fast Workers the four varieties of frustration[276] are so well integrated among themselves that it is difficult, if not impossible to say where one ends and another begins. These interrelations make it one of the most perplexing of Browning's films, especially with regard to morality and justice.[170]

The betrayals, humiliations and retaliations that plague the characters, and the moral legitimacy of their behaviors remains unresolved. Rosenthal comments on Browning's ambivalence: "Fast Workers is Browning's final cynical word on the impossibility of an individual obtaining justice, however righteous his cause, without critically sullying himself. Superficially, things have been set right. Gunner and Bucker are again friends and, together are equal to any wily female. Yet Gunner, the individual who is the most culpable, finds himself in the most secure position, while the basically well-intentioned Mary is rejected and condemned by both men."[277] An outstanding example of Browning's ability to visually convey terror—a technique he developed in the silent era—is demonstrated when Mary perceives that Bucker, cuckolded by Gunner, reveals his homicidal rage.[278]

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer committed $525,000 to the film's production budget, quite a high sum for a relatively short feature. Ultimately, MGM reported earnings of only $165,000 on the film after its release, resulting in a net loss of $360,000 on the motion picture.[279]

Mark of the Vampire (1935)

Browning returned to a vampire-themed picture with his 1935 Mark of the Vampire.[280] Rather than risk a legal battle with Universal Studios who held the rights to Browning's 1931 Dracula, he opted for a reprise of his successful silent era London After Midnight (1927), made for MGM and starring Lon Chaney in a dual role.[281]

With Mark of the Vampire, Browning follows the plot conceit employed in London After Midnight: An investigator and hypnotist seeks to expose a murderer by means of a "vampire masquerade" so as to elicit his confession.[282] Browning deviates from his 1927 silent film in that here the sleuth, Professor Zelen (Lionel Barrymore),[283] rather than posing as a vampire himself in a dual role, hires a troupe of talented thespians to stage an elaborate hoax to deceive the murder suspect Baron Otto von Zinden (Jean Hersholt).[284] Bela Lugosi was enlisted to play the lead vampire in the troupe, Count Moro.[285] As a direct descendant of Browning's carnival-themed films, Browning offers the movie audience a generous dose of Gothic iconography: "hypnotic trances, flapping bats, spooky graveyards, moaning organs, cobwebs thick as curtains – and bound it all together with bits of obscure Eastern European folklore..."[286]

As such, Mark of the Vampire leads the audience to suspend disbelief in their skepticism regarding vampires through a series of staged illusions, only to sharply disabuse them of their credulity in the final minutes of the movie.[287][288] Browning reportedly composed the conventional plot scenes as he would a stage production, but softened the static impression through the editing process. In scenes that depicted the supernatural, Browning freely used a moving camera. Film historian Matthew Sweney observes "the [special] effects shots...overpower the static shots in which the film's plot and denouement take place...creating a visual tension in the film."

Cinematographer James Wong Howe's lighting methods endowed the film with a spectral quality that complimented Browning's "sense of the unreal".[289] Critic Stuart Rosenthal writes:

"The delicate, silkily evil texture [that characterizes the imagery] is as much a triumph for James Wong Howe's lighting as it is for Browning's sense of the unreal. Howe has bathed his sets in the luminous glow which is free of the harsh shadows and contrasts that mark Freund's work in Dracula."[290]

Mark of the Vampire is widely cited for its famous "tracking shot on the stairwell" in which Count Mora (Bela Lugosi) and his daughter Luna (Carol Borland) descend in a stately promenade. Browning inter-cuts their progress with images of vermin and venomous insects, visual equivalents for the vampires as they emerge from their own crypts in search of sustenance.[291] Rosenthal describes the one-minute sequence:

"...Bela Lugosi and the bat-girl [Carol Borland] descend the cobweb-covered staircase of the abandoned mansion, their progress broken into a series of shots, each of which involves continuous movement of either the camera, the players, or both. This creates the impression of a steady, unearthly gliding motion...the glimpses of bats, rats and insects accent the steady, deliberate progress of the horrific pair…the effect is disorienting and the viewer becomes ill-at-ease because he is entirely outside his realm of natural experience."[292]

In another notable and "exquisitely edited" scene Browning presents a lesbian-inspired seduction. Count Mora, in the form of a bat, summons Luna to the cemetery where Irene Borotyn (Elizabeth Allan) (daughter of murder victim Sir Karell, awaits in a trance.) When vampire Luna avidly embraces her victim, Count Moro voyeuristically looks on approvingly. Borland's Luna would inspire the character Morticia in the TV series The Addams Family.[293]

The soundtrack for Mark of the Vampire is notable in that it employs no orchestral music aside from accompanying the opening and closing credits. Melodic passages, when heard, are provided only by the players. The sound effects provided by recording director Douglas Shearer contribute significantly to the film's ambiance.[294] [295] Film historian Matthew Sweney writes:

"The only incidental music...consisting as it does with groans and nocturnal animal sounds is perhaps minimalistic, but it is not used minimally, occurring throughout film expressly to score the vampire scenes...frightning scenes are not punctuated with orchestral crescendos, but by babies crying, women screaming, horses neighing, bells striking."[296]

The climatic coup-de-grace occurs when the murderer's incredulity regarding the existence of vampires is reversed when Browning cinematically creates an astonishing illusion of the winged Luna in flight transforming into a human. The rationalist Baron Otto, a witness to this legerdemain, is converted into a believer in the supernatural and ultimately confesses, under hypnosis, to the murder of his brother Sir Karell.[297]

In the final five minutes of Mark of the Vampire, the theatre audience is confronted with the "theatrical trap" that Browning has laid throughout the picture: none of the supernatural elements of film are genuine—the "vampires" are merely actors engaged in a deception. This is made explicit when Bela Lugosi, no longer in character as Count Moro, declares to a fellow actor: "Did you see me? I was greater than any real vampire!"[298]

The Devil-Doll (1936)

Browning created a work reminiscent of his collaborations with actor Lon Chaney in the "bizarre melodrama" The Devil-Doll.[299]

Based on the novel Burn, Witch, Burn (1932) by Abraham Merritt, the script was crafted by Browning with contributions from Garrett Fort, Guy Endore and Erich von Stroheim (director of Greed (1924) and Foolish Wives (1922)), and "although it has its horrific moments, like Freaks (1932), The Devil-Doll is not a horror film."[300]

In The Devil-Doll, Browning borrows a number of the plot devices from his 1925 The Unholy Three.[301]

Paul Lavond (Lionel Barrymore) has spent 17 years incarcerated at Devil's Island, framed for murder and embezzlement committed by his financial associates. He escapes from the prison with fellow inmate, the ailing Marcel (Henry B. Walthall). The terminally ill scientist divulges to Lavond his secret formula for transforming humans into miniature, animated puppets. In alliance with Marcel's widow Malita (Rafaela Ottiano), the vengeful Lavond unleashes an army of tiny living "dolls" to exact a terrible retribution against the three "unholy" bankers.[302] Biographer Vivian Sobchack acknowledges that "the premises on which the revenge plot rest are incredible, but the visual realization is so fascinating that we are drawn, nonetheless, into a world that seems quite credible and moving" and reminds viewers that "there are some rather comic scenes in the film..."[303]

Barrymore's dual role as Lavond and his cross-dressing persona, the elderly Madame Mandilip, a doll shop proprietor, is strikingly similar to Lon Chaney's Professor Echo and his transvestite counterpart "Granny" O'Grady, a parrot shop owner in The Unholy Three (1925). [304] Film critic Stuart Rosenthal notes that Browning recycling of this characterization as a plot device "is further evidence for the interchangeability of Browning's heroes, all of whom would act identically if given the same set of circumstances."[305]

Thematically, The Devil-Doll presents a version of Browning "indirect" sexual frustration.[306] Here, Lavond's daughter Lorraine (Maureen O'Sullivan), ignorant of her father's identity, remains so. Stuart Rothenthal explains:

"Lionel Barrymore in The Devil-Doll makes an attempt [as did Lon Chaney in The Road to Mandalay (1926) and West of Zanzibar (1928)] to protect his daughter from embarrassment and unhappiness by concealing his identity from her even after he has been cleared of embezzlement. In an ironic way, by denying himself his daughter, he is punishing himself for the crimes he committed in the course of his self-exoneration...Clearly, the most deplorable consequence [of his frameup] was not the years he spent in prison, but the alienation of his daughter's love and respect."[307]

Rosenthal points out another parallel between The Devil-Doll and The Unholy Three (1925): "Lavond's concern for his daughter and refusal to misuse his powers mark him as a good man...when his revenge is complete, like Echo [in The Unholy Three], Lavond demonstrates a highly beneficent nature."[308]

Browning proficient use of the camera and the remarkable special effects depicting the "miniature" people are both disturbing and fascinating, directed with "eerie skill."[309]

Film historians Stefanie Diekmann and Ekkehard Knörer report that the only direct link between Browning's fascination with "the grotesque, the deformed and the perverse"[79] and the traditions of the French Grand Guignol is actor Rafaela Ottiano who plays doll-obsessed scientist Matila. Before her supporting role in The Devil-Doll, she enjoyed "a distinguished career as a Grand Guignol performer."[310]

Shortly after the completion of The Devil-Doll, Irving Thalberg, Browning's mentor at MGM, died at age 37. It would be two years before his final film: Miracles for Sale (1939).[311]

Miracles for Sale (1939)

Miracles for Sale (1939) was the last of Browning's 46 feature films since he began directing in 1917.[54][312] Browning's career had been in abeyance for two years after completing The Devil-Doll in 1936.[313]

In 1939, he was tasked with adapting Clayton Rawson's locked-room mystery, Death from a Top Hat (1938).