Bede

Bede the Venerable | |

|---|---|

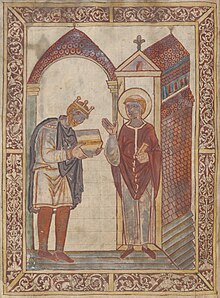

The Venerable Bede writing. Detail from a 12th-century codex. | |

| Church Father, Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | c. 673[1] Kingdom of Northumbria, possibly Monkwearmouth in present-day Sunderland, Tyne and Wear, England[1] |

| Died | 26 May 735 (aged 61 or 62) Jarrow, Northumbria[1] |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church,[2] Anglican Communion, and Lutheranism |

| Canonized | Declared a Doctor of the Church in 1899 by Pope Leo XIII, Rome |

| Major shrine | Durham Cathedral, England |

| Feast |

|

| Attributes | Holding the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, a quill, a biretta |

| Patronage | English writers and historians; Jarrow, Tyne and Wear, England, Beda College, San Beda University, San Beda College Alabang |

| Influences | |

Bede (/biːd/; Old English: Bēda [ˈbeːdɑ]; 672/3 – 26 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable (Latin: Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk, author and scholar. He was one of the greatest teachers and writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most famous work, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, gained him the title "The Father of English History". He served at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom of Northumbria of the Angles.

Born on lands belonging to the twin monastery of Monkwearmouth–Jarrow in present-day Tyne and Wear, England, Bede was sent to Monkwearmouth at the age of seven and later joined Abbot Ceolfrith at Jarrow. Both of them survived a plague that struck in 686 and killed the majority of the population there. While Bede spent most of his life in the monastery, he travelled to several abbeys and monasteries across the British Isles, even visiting the archbishop of York and King Ceolwulf of Northumbria.

His theological writings were extensive and included a number of Biblical commentaries and other works of exegetical erudition. Another important area of study for Bede was the academic discipline of computus, otherwise known to his contemporaries as the science of calculating calendar dates. One of the more important dates Bede tried to compute was Easter, an effort that was mired in controversy. He also helped popularize the practice of dating forward from the birth of Christ (Anno Domini—in the year of our Lord), a practice which eventually became commonplace in medieval Europe. He is considered by many historians to be the most important scholar of antiquity for the period between the death of Pope Gregory I in 604 and the coronation of Charlemagne in 800.

In 1899, Pope Leo XIII declared him a Doctor of the Church. He is the only native of Great Britain to achieve this designation.[a] Bede was moreover a skilled linguist and translator, and his work made the Latin and Greek writings of the early Church Fathers much more accessible to his fellow Anglo-Saxons, which contributed significantly to English Christianity. Bede's monastery had access to an impressive library which included works by Eusebius, Orosius, and many others.

Life

Almost everything that is known of Bede's life is contained in the last chapter of his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, a history of the church in England. It was completed in about 731,[5] and Bede implies that he was then in his fifty-ninth year, which would give a birth date in 672 or 673.[1][6][7][b] A minor source of information is the letter by his disciple Cuthbert (not to be confused with the saint, Cuthbert, who is mentioned in Bede's work) which relates Bede's death.[11][c] Bede, in the Historia, gives his birthplace as "on the lands of this monastery".[12] He is referring to the twin monasteries of Monkwearmouth and Jarrow,[13] in modern-day Wearside and Tyneside respectively. There is also a tradition that he was born at Monkton, two miles from the site where the monastery at Jarrow was later built.[1][14] Bede says nothing of his origins, but his connections with men of noble ancestry suggest that his own family was well-to-do.[15] Bede's first abbot was Benedict Biscop, and the names "Biscop" and "Beda" both appear in a list of the kings of Lindsey from around 800, further suggesting that Bede came from a noble family.[7]

Bede's name reflects West Saxon Bīeda (Anglian Bēda).[16] It is an Old English short name formed on the root of bēodan "to bid, command".[17] The name also occurs in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, s.a. 501, as Bieda, one of the sons of the Saxon founder of Portsmouth. The Liber Vitae of Durham Cathedral names two priests with this name, one of whom is presumably Bede himself. Some manuscripts of the Life of Cuthbert, one of Bede's works, mention that Cuthbert's own priest was named Bede; it is possible that this priest is the other name listed in the Liber Vitae.[18][19]

At the age of seven, Bede was sent as a puer oblatus[20] to the monastery of Monkwearmouth by his family to be educated by Benedict Biscop and later by Ceolfrith.[21] Bede does not say whether it was already intended at that point that he would be a monk.[22] It was fairly common in Ireland at this time for young boys, particularly those of noble birth, to be fostered out as an oblate; the practice was also likely to have been common among the Germanic peoples in England.[23] Monkwearmouth's sister monastery at Jarrow was founded by Ceolfrith in 682, and Bede probably transferred to Jarrow with Ceolfrith that year.[13]

The dedication stone for the church has survived as of 1969; it is dated 23 April 685, and as Bede would have been required to assist with menial tasks in his day-to-day life it is possible that he helped in building the original church.[23] In 686, plague broke out at Jarrow. The Life of Ceolfrith, written in about 710, records that only two surviving monks were capable of singing the full offices; one was Ceolfrith and the other a young boy, who according to the anonymous writer had been taught by Ceolfrith. The two managed to do the entire service of the liturgy until others could be trained. The young boy was almost certainly Bede, who would have been about 14.[21][24]

When Bede was about 17 years old, Adomnán, the abbot of Iona Abbey, visited Monkwearmouth and Jarrow. Bede would probably have met the abbot during this visit, and it may be that Adomnán sparked Bede's interest in the Easter dating controversy.[25] In about 692, in Bede's nineteenth year, Bede was ordained a deacon by his diocesan bishop, John, who was bishop of Hexham. The canonical age for the ordination of a deacon was 25; Bede's early ordination may mean that his abilities were considered exceptional,[23] but it is also possible that the minimum age requirement was often disregarded.[26] There might have been minor orders ranking below a deacon; but there is no record of whether Bede held any of these offices.[9][d] In Bede's thirtieth year (about 702), he became a priest, with the ordination again performed by Bishop John.[7]

In about 701 Bede wrote his first works, the De Arte Metrica and De Schematibus et Tropis; both were intended for use in the classroom.[26] He continued to write for the rest of his life, eventually completing over 60 books, most of which have survived. Not all his output can be easily dated, and Bede may have worked on some texts over a period of many years.[7][26] His last surviving work is a letter to Ecgbert of York, a former student, written in 734.[26] A 6th-century Greek and Latin manuscript of Acts of the Apostles that is believed to have been used by Bede survives and is now in the Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford. It is known as the Codex Laudianus.[27][28]

Bede may have worked on some of the Latin Bibles that were copied at Jarrow, one of which, the Codex Amiatinus, is now held by the Laurentian Library in Florence.[29] Bede was a teacher as well as a writer;[30] he enjoyed music and was said to be accomplished as a singer and as a reciter of poetry in the vernacular.[26] It is possible that he suffered a speech impediment, but this depends on a phrase in the introduction to his verse life of St Cuthbert. Translations of this phrase differ, and it is uncertain whether Bede intended to say that he was cured of a speech problem, or merely that he was inspired by the saint's works.[31][32][e]

In 708, some monks at Hexham accused Bede of having committed heresy in his work De Temporibus.[33] The standard theological view of world history at the time was known as the Six Ages of the World; in his book, Bede calculated the age of the world for himself, rather than accepting the authority of Isidore of Seville, and came to the conclusion that Christ had been born 3,952 years after the creation of the world, rather than the figure of over 5,000 years that was commonly accepted by theologians.[34] The accusation occurred in front of the bishop of Hexham, Wilfrid, who was present at a feast when some drunken monks made the accusation. Wilfrid did not respond to the accusation, but a monk present relayed the episode to Bede, who replied within a few days to the monk, writing a letter setting forth his defence and asking that the letter also be read to Wilfrid.[33][f] Bede had another brush with Wilfrid, for the historian says that he met Wilfrid sometime between 706 and 709 and discussed Æthelthryth, the abbess of Ely. Wilfrid had been present at the exhumation of her body in 695, and Bede questioned the bishop about the exact circumstances of the body and asked for more details of her life, as Wilfrid had been her advisor.[35]

In 733, Bede travelled to York to visit Ecgbert, who was then bishop of York. The See of York was elevated to an archbishopric in 735, and it is likely that Bede and Ecgbert discussed the proposal for the elevation during his visit.[36] Bede hoped to visit Ecgbert again in 734 but was too ill to make the journey.[36] Bede also travelled to the monastery of Lindisfarne and at some point visited the otherwise unknown monastery of a monk named Wicthed, a visit that is mentioned in a letter to that monk. Because of his widespread correspondence with others throughout the British Isles, and because many of the letters imply that Bede had met his correspondents, it is likely that Bede travelled to some other places, although nothing further about timing or locations can be guessed.[37]

It seems certain that he did not visit Rome, however, as he did not mention it in the autobiographical chapter of his Historia Ecclesiastica.[38] Nothhelm, a correspondent of Bede's who assisted him by finding documents for him in Rome, is known to have visited Bede, though the date cannot be determined beyond the fact that it was after Nothhelm's visit to Rome.[39] Except for a few visits to other monasteries, his life was spent in a round of prayer, observance of the monastic discipline and study of the Sacred Scriptures.[40] He was considered the most learned man of his time.[41]

Bede died at Jarrow on the Feast of the Ascension, 26 May 735 and was buried there.[7] Cuthbert, a disciple of Bede's, wrote a letter to a Cuthwin (of whom nothing else is known), describing Bede's last days and his death. According to Cuthbert, Bede fell ill, "with frequent attacks of breathlessness but almost without pain", before Easter. On the Tuesday, two days before Bede died, his breathing became worse and his feet swelled. He continued to dictate to a scribe, however, and despite spending the night awake in prayer he dictated again the following day.[42]

At three o'clock, according to Cuthbert, he asked for a box of his to be brought and distributed among the priests of the monastery "a few treasures" of his: "some pepper, and napkins, and some incense". That night he dictated a final sentence to the scribe, a boy named Wilberht, and died soon afterwards.[42] The account of Cuthbert does not make entirely clear whether Bede died before midnight or after. However, by the reckoning of Bede's time, passage from the old day to the new occurred at sunset, not midnight, and Cuthbert is clear that he died after sunset. Thus, while his box was brought at three o'clock Wednesday afternoon of 25 May, by the time of the final dictation it was considered 26 May, although it might still have been 25 May in modern usage.[43]

Cuthbert's letter also relates a five-line poem in the vernacular that Bede composed on his deathbed, known as "Bede's Death Song". It is the most-widely copied Old English poem and appears in 45 manuscripts, but its attribution to Bede is not certain—not all manuscripts name Bede as the author, and the ones that do are of later origin than those that do not.[44][45][46] Bede's remains may have been translated to Durham Cathedral in the 11th century; his tomb there was looted in 1541, but the contents were probably re-interred in the Galilee chapel at the cathedral.[7]

One further oddity in his writings is that in one of his works, the Commentary on the Seven Catholic Epistles, he writes in a manner that gives the impression he was married.[18] The section in question is the only one in that work that is written in first-person view. Bede says: "Prayers are hindered by the conjugal duty because as often as I perform what is due to my wife I am not able to pray."[47] Another passage, in the Commentary on Luke, also mentions a wife in the first person: "Formerly I possessed a wife in the lustful passion of desire and now I possess her in honourable sanctification and true love of Christ."[47] The historian Benedicta Ward argued that these passages are Bede employing a rhetorical device.[48]

Works

Bede wrote scientific, historical and theological works, reflecting the range of his writings from music and metrics to exegetical Scripture commentaries. He knew patristic literature, as well as Pliny the Elder, Virgil, Lucretius, Ovid, Horace and other classical writers. He knew some Greek. Bede's scriptural commentaries employed the allegorical method of interpretation,[49] and his history includes accounts of miracles, which to modern historians has seemed at odds with his critical approach to the materials in his history. Modern studies have shown the important role such concepts played in the world-view of Early Medieval scholars.[50] Although Bede is mainly studied as a historian now, in his time his works on grammar, chronology, and biblical studies were as important as his historical and hagiographical works. The non-historical works contributed greatly to the Carolingian Renaissance.[51] He has been credited with writing a penitential, though his authorship of this work is disputed.[52]

Ecclesiastical History of the English People

Bede's best-known work is the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, or An Ecclesiastical History of the English People,[53] completed in about 731. Bede was aided in writing this book by Albinus, abbot of St Augustine's Abbey, Canterbury.[54] The first of the five books begins with some geographical background and then sketches the history of England, beginning with Caesar's invasion in 55 BC.[55] A brief account of Christianity in Roman Britain, including the martyrdom of St Alban, is followed by the story of Augustine's mission to England in 597, which brought Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons.[7]

The second book begins with the death of Gregory the Great in 604 and follows the further progress of Christianity in Kent and the first attempts to evangelise Northumbria.[56] These ended in disaster when Penda, the pagan king of Mercia, killed the newly Christian Edwin of Northumbria at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in about 632.[56] The setback was temporary, and the third book recounts the growth of Christianity in Northumbria under kings Oswald of Northumbria and Oswy.[57] The climax of the third book is the account of the Council of Whitby, traditionally seen as a major turning point in English history.[58] The fourth book begins with the consecration of Theodore as Archbishop of Canterbury and recounts Wilfrid's efforts to bring Christianity to the Kingdom of Sussex.[59]

The fifth book brings the story up to Bede's day and includes an account of missionary work in Frisia and of the conflict with the British church over the correct dating of Easter.[59] Bede wrote a preface for the work, in which he dedicates it to Ceolwulf, king of Northumbria.[60] The preface mentions that Ceolwulf received an earlier draft of the book; presumably Ceolwulf knew enough Latin to understand it, and he may even have been able to read it.[7][55] The preface makes it clear that Ceolwulf had requested the earlier copy, and Bede had asked for Ceolwulf's approval; this correspondence with the king indicates that Bede's monastery had connections among the Northumbrian nobility.[7]

Sources

The monastery at Wearmouth-Jarrow had an excellent library. Both Benedict Biscop and Ceolfrith had acquired books from the Continent, and in Bede's day the monastery was a renowned centre of learning.[61] It has been estimated that there were about 200 books in the monastic library.[62]

For the period prior to Augustine's arrival in 597, Bede drew on earlier writers, including Solinus.[7][63] He had access to two works of Eusebius: the Historia Ecclesiastica, and also the Chronicon, though he had neither in the original Greek; instead he had a Latin translation of the Historia, by Rufinus, and Jerome's translation of the Chronicon.[64] He also knew Orosius's Adversus Paganus, and Gregory of Tours' Historia Francorum, both Christian histories,[64] as well as the work of Eutropius, a pagan historian.[65] He used Constantius's Life of Germanus as a source for Germanus's visits to Britain.[7][63]

Bede's account of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is drawn largely from Gildas's De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae.[66] Bede would also have been familiar with more recent accounts such as Stephen of Ripon's Life of Wilfrid, and anonymous Life of Gregory the Great and Life of Cuthbert.[63] He also drew on Josephus's Antiquities, and the works of Cassiodorus,[67] and there was a copy of the Liber Pontificalis in Bede's monastery.[68] Bede quotes from several classical authors, including Cicero, Plautus, and Terence, but he may have had access to their work via a Latin grammar rather than directly.[3] However, it is clear he was familiar with the works of Virgil and with Pliny the Elder's Natural History, and his monastery also owned copies of the works of Dionysius Exiguus.[3]

He probably drew his account of Alban from a life of that saint which has not survived. He acknowledges two other lives of saints directly; one is a life of Fursa, and the other of Æthelburh; the latter no longer survives.[69] He also had access to a life of Ceolfrith.[70] Some of Bede's material came from oral traditions, including a description of the physical appearance of Paulinus of York, who had died nearly 90 years before Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica was written.[70]

Bede had correspondents who supplied him with material. Albinus, the abbot of the monastery in Canterbury, provided much information about the church in Kent, and with the assistance of Nothhelm, at that time a priest in London, obtained copies of Gregory the Great's correspondence from Rome relating to Augustine's mission.[7][63][71] Almost all of Bede's information regarding Augustine is taken from these letters.[7] Bede acknowledged his correspondents in the preface to the Historia Ecclesiastica;[72] he was in contact with Bishop Daniel of Winchester, for information about the history of the church in Wessex and also wrote to the monastery at Lastingham for information about Cedd and Chad.[72] Bede also mentions an Abbot Esi as a source for the affairs of the East Anglian church, and Bishop Cynibert for information about Lindsey.[72]

The historian Walter Goffart argues that Bede based the structure of the Historia on three works, using them as the framework around which the three main sections of the work were structured. For the early part of the work, up until the Gregorian mission, Goffart feels that Bede used De excidio. The second section, detailing the Gregorian mission of Augustine of Canterbury was framed on Life of Gregory the Great written at Whitby. The last section, detailing events after the Gregorian mission, Goffart feels was modelled on Life of Wilfrid.[73] Most of Bede's informants for information after Augustine's mission came from the eastern part of Britain, leaving significant gaps in the knowledge of the western areas, which were those areas likely to have a native Briton presence.[74][75]

Models and style

Bede's stylistic models included some of the same authors from whom he drew the material for the earlier parts of his history. His introduction imitates the work of Orosius,[7] and his title is an echo of Eusebius's Historia Ecclesiastica.[1] Bede also followed Eusebius in taking the Acts of the Apostles as the model for the overall work: where Eusebius used the Acts as the theme for his description of the development of the church, Bede made it the model for his history of the Anglo-Saxon church.[76] Bede quoted his sources at length in his narrative, as Eusebius had done.[7] Bede also appears to have taken quotes directly from his correspondents at times. For example, he almost always uses the terms "Australes" and "Occidentales" for the South and West Saxons respectively, but in a passage in the first book he uses "Meridiani" and "Occidui" instead, as perhaps his informant had done.[7] At the end of the work, Bede adds a brief autobiographical note; this was an idea taken from Gregory of Tours' earlier History of the Franks.[77]

Bede's work as a hagiographer and his detailed attention to dating were both useful preparations for the task of writing the Historia Ecclesiastica. His interest in computus, the science of calculating the date of Easter, was also useful in the account he gives of the controversy between the British and Anglo-Saxon church over the correct method of obtaining the Easter date.[53]

Bede is described by Michael Lapidge as "without question the most accomplished Latinist produced in these islands in the Anglo-Saxon period".[78] His Latin has been praised for its clarity, but his style in the Historia Ecclesiastica is not simple. He knew rhetoric and often used figures of speech and rhetorical forms which cannot easily be reproduced in translation, depending as they often do on the connotations of the Latin words. However, unlike contemporaries such as Aldhelm, whose Latin is full of difficulties, Bede's own text is easy to read.[79] In the words of Charles Plummer, one of the best-known editors of the Historia Ecclesiastica, Bede's Latin is "clear and limpid ... it is very seldom that we have to pause to think of the meaning of a sentence ... Alcuin rightly praises Bede for his unpretending style."[80]

Intent

Bede's primary intention in writing the Historia Ecclesiastica was to show the growth of the united church throughout England. The native Britons, whose Christian church survived the departure of the Romans, earn Bede's ire for refusing to help convert the Anglo-Saxons; by the end of the Historia the English, and their church, are dominant over the Britons.[81] This goal, of showing the movement towards unity, explains Bede's animosity towards the British method of calculating Easter: much of the Historia is devoted to a history of the dispute, including the final resolution at the Synod of Whitby in 664.[77] Bede is also concerned to show the unity of the English, despite the disparate kingdoms that still existed when he was writing. He also wants to instruct the reader by spiritual example and to entertain, and to the latter end he adds stories about many of the places and people about which he wrote.[81]

N. J. Higham argues that Bede designed his work to promote his reform agenda to Ceolwulf, the Northumbrian king. Bede painted a highly optimistic picture of the current situation in the Church, as opposed to the more pessimistic picture found in his private letters.[82]

Bede's extensive use of miracles can prove difficult for readers who consider him a more or less reliable historian but do not accept the possibility of miracles. Yet both reflect an inseparable integrity and regard for accuracy and truth, expressed in terms both of historical events and of a tradition of Christian faith that continues. Bede, like Gregory the Great whom Bede quotes on the subject in the Historia, felt that faith brought about by miracles was a stepping stone to a higher, truer faith, and that as a result miracles had their place in a work designed to instruct.[83]

Omissions and biases

Bede is somewhat reticent about the career of Wilfrid, a contemporary and one of the most prominent clerics of his day. This may be because Wilfrid's opulent lifestyle was uncongenial to Bede's monastic mind; it may also be that the events of Wilfrid's life, divisive and controversial as they were, simply did not fit with Bede's theme of the progression to a unified and harmonious church.[56]

Bede's account of the early migrations of the Angles and Saxons to England omits any mention of a movement of those peoples across the English Channel from Britain to Brittany described by Procopius, who was writing in the sixth century. Frank Stenton describes this omission as "a scholar's dislike of the indefinite"; traditional material that could not be dated or used for Bede's didactic purposes had no interest for him.[84]

Bede was a Northumbrian, and this tinged his work with a local bias.[85] The sources to which he had access gave him less information about the west of England than for other areas.[86] He says relatively little about the achievements of Mercia and Wessex, omitting, for example, any mention of Boniface, a West Saxon missionary to the continent of some renown and of whom Bede had almost certainly heard, though Bede does discuss Northumbrian missionaries to the continent. He is also parsimonious in his praise for Aldhelm, a West Saxon who had done much to convert the native Britons to the Roman form of Christianity. He lists seven kings of the Anglo-Saxons whom he regards as having held imperium, or overlordship; only one king of Wessex, Ceawlin, is listed as Bretwalda, and none from Mercia, though elsewhere he acknowledges the secular power several of the Mercians held.[87] Historian Robin Fleming states that he was so hostile to Mercia because Northumbria had been diminished by Mercian power that he consulted no Mercian informants and included no stories about its saints.[88]

Bede relates the story of Augustine's mission from Rome, and tells how the British clergy refused to assist Augustine in the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons. This, combined with Gildas's negative assessment of the British church at the time of the Anglo-Saxon invasions, led Bede to a very critical view of the native church. However, Bede ignores the fact that at the time of Augustine's mission, the history between the two was one of warfare and conquest, which, in the words of Barbara Yorke, would have naturally "curbed any missionary impulses towards the Anglo-Saxons from the British clergy."[89]

Use of Anno Domini

At the time Bede wrote the Historia Ecclesiastica, there were two common ways of referring to dates. One was to use indictions, which were 15-year cycles, counting from 312 AD. There were three different varieties of indiction, each starting on a different day of the year. The other approach was to use regnal years—the reigning Roman emperor, for example, or the ruler of whichever kingdom was under discussion. This meant that in discussing conflicts between kingdoms, the date would have to be given in the regnal years of all the kings involved. Bede used both these approaches on occasion but adopted a third method as his main approach to dating: the Anno Domini method invented by Dionysius Exiguus.[90] Although Bede did not invent this method, his adoption of it and his promulgation of it in De Temporum Ratione, his work on chronology, is the main reason it is now so widely used.[90][91] Bede's Easter table, contained in De Temporum Ratione, was developed from Dionysius Exiguus' Easter table.

Assessment

The Historia Ecclesiastica was copied often in the Middle Ages, and about 160 manuscripts containing it survive. About half of those are located on the European continent, rather than in the British Isles.[92] Most of the 8th- and 9th-century texts of Bede's Historia come from the northern parts of the Carolingian Empire.[93] This total does not include manuscripts with only a part of the work, of which another 100 or so survive. It was printed for the first time between 1474 and 1482, probably at Strasbourg.[92]

Modern historians have studied the Historia extensively, and several editions have been produced.[94] For many years, early Anglo-Saxon history was essentially a retelling of the Historia, but recent scholarship has focused as much on what Bede did not write as what he did. The belief that the Historia was the culmination of Bede's works, the aim of all his scholarship, was a belief common among historians in the past but is no longer accepted by most scholars.[95]

Modern historians and editors of Bede have been lavish in their praise of his achievement in the Historia Ecclesiastica. Stenton regards it as one of the "small class of books which transcend all but the most fundamental conditions of time and place", and regards its quality as dependent on Bede's "astonishing power of co-ordinating the fragments of information which came to him through tradition, the relation of friends, or documentary evidence ... In an age where little was attempted beyond the registration of fact, he had reached the conception of history."[96] Patrick Wormald describes him as "the first and greatest of England's historians".[97]

The Historia Ecclesiastica has given Bede a high reputation, but his concerns were different from those of a modern writer of history.[7] His focus on the history of the organisation of the English church, and on heresies and the efforts made to root them out, led him to exclude the secular history of kings and kingdoms except where a moral lesson could be drawn or where they illuminated events in the church.[7] Besides the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the medieval writers William of Malmesbury, Henry of Huntingdon, and Geoffrey of Monmouth used his works as sources and inspirations.[98] Early modern writers, such as Polydore Vergil and Matthew Parker, the Elizabethan Archbishop of Canterbury, also utilised the Historia, and his works were used by both Protestant and Catholic sides in the wars of religion.[99]

Some historians have questioned the reliability of some of Bede's accounts. One historian, Charlotte Behr, thinks that the Historia's account of the arrival of the Germanic invaders in Kent should not be considered to relate what actually happened, but rather relates myths that were current in Kent during Bede's time.[100]

It is likely that Bede's work, because it was so widely copied, discouraged others from writing histories and may even have led to the disappearance of manuscripts containing older historical works.[101]

Other historical works

Chronicles

As Chapter 66 of his On the Reckoning of Time, in 725 Bede wrote the Greater Chronicle (chronica maiora), which sometimes circulated as a separate work. For recent events the Chronicle, like his Ecclesiastical History, relied upon Gildas, upon a version of the Liber Pontificalis current at least to the papacy of Pope Sergius I (687–701), and other sources. For earlier events he drew on Eusebius's Chronikoi Kanones. The dating of events in the Chronicle is inconsistent with his other works, using the era of creation, the Anno Mundi.[103]

Hagiography

His other historical works included lives of the abbots of Wearmouth and Jarrow, as well as verse and prose lives of St Cuthbert, an adaptation of Paulinus of Nola's Life of St Felix, and a translation of the Greek Passion of St Anastasius. He also created a listing of saints, the Martyrology.[104]

Theological works

In his own time, Bede was as well known for his biblical commentaries, and for his exegetical and other theological works. The majority of his writings were of this type and covered the Old Testament and the New Testament. Most survived the Middle Ages, but a few were lost.[105] It was for his theological writings that he earned the title of Doctor Anglorum and why he was declared a saint.[4]

Bede synthesised and transmitted the learning from his predecessors, as well as made careful, judicious innovation in knowledge (such as recalculating the age of the Earth—for which he was censured before surviving the heresy accusations and eventually having his views championed by Archbishop Ussher in the sixteenth century—see below) that had theological implications. In order to do this, he learned Greek and attempted to learn Hebrew. He spent time reading and rereading both the Old and the New Testaments. He mentions that he studied from a text of Jerome's Vulgate, which itself was from the Hebrew text.[3][4]

He also studied both the Latin and the Greek Fathers of the Church. In the monastic library at Jarrow were numerous books by theologians, including works by Basil, Cassian, John Chrysostom, Isidore of Seville, Origen, Gregory of Nazianzus, Augustine of Hippo, Jerome, Pope Gregory I, Ambrose of Milan, Cassiodorus, and Cyprian.[3][4] He used these, in conjunction with the Biblical texts themselves, to write his commentaries and other theological works.[4]

He had a Latin translation by Evagrius of Athanasius's Life of Antony and a copy of Sulpicius Severus' Life of St Martin.[3] He also used lesser known writers, such as Fulgentius, Julian of Eclanum, Tyconius, and Prosper of Aquitaine. Bede was the first to refer to Jerome, Augustine, Pope Gregory and Ambrose as the four Latin Fathers of the Church.[106] It is clear from Bede's own comments that he felt his calling was to explain to his students and readers the theology and thoughts of the Church Fathers.[107]

Bede also wrote homilies, works written to explain theology used in worship services. He wrote homilies on the major Christian seasons such as Advent, Lent, or Easter, as well as on other subjects such as anniversaries of significant events.[4]

Both types of Bede's theological works circulated widely in the Middle Ages. Several of his biblical commentaries were incorporated into the Glossa Ordinaria, an 11th-century collection of biblical commentaries. Some of Bede's homilies were collected by Paul the Deacon, and they were used in that form in the Monastic Office. Boniface used Bede's homilies in his missionary efforts on the continent.[4]

Bede sometimes included in his theological books an acknowledgement of the predecessors on whose works he drew. In two cases he left instructions that his marginal notes, which gave the details of his sources, should be preserved by the copyist, and he may have originally added marginal comments about his sources to others of his works. Where he does not specify, it is still possible to identify books to which he must have had access by quotations that he uses. A full catalogue of the library available to Bede in the monastery cannot be reconstructed, but it is possible to tell, for example, that Bede was very familiar with the works of Virgil.[108][g]

There is little evidence that he had access to any other of the pagan Latin writers—he quotes many of these writers, but the quotes are almost always found in the Latin grammars that were common in his day, one or more of which would certainly have been at the monastery. Another difficulty is that manuscripts of early writers were often incomplete: it is apparent that Bede had access to Pliny's Encyclopaedia, for example, but it seems that the version he had was missing book xviii, since he did not quote from it in his De temporum ratione.[108][h]

Bede's works included Commentary on Revelation,[109] Commentary on the Catholic Epistles,[110] Commentary on Acts, Reconsideration on the Books of Acts,[111] On the Gospel of Mark, On the Gospel of Luke, and Homilies on the Gospels.[112] At the time of his death he was working on a translation of the Gospel of John into English.[113][114] He did this for the last 40 days of his life. When the last passage had been translated he said: "All is finished."[41] The works dealing with the Old Testament included Commentary on Samuel,[115] Commentary on Genesis,[116] Commentaries on Ezra and Nehemiah, On the Temple, On the Tabernacle,[117] Commentaries on Tobit, Commentaries on Proverbs,[118] Commentaries on the Song of Songs, Commentaries on the Canticle of Habakkuk.[119] The works on Ezra, the tabernacle and the temple were especially influenced by Gregory the Great's writings.[120]

Historical and astronomical chronology

De temporibus, or On Time, written in about 703, provides an introduction to the principles of Easter computus.[121] This was based on parts of Isidore of Seville's Etymologies, and Bede also included a chronology of the world which was derived from Eusebius, with some revisions based on Jerome's translation of the Bible.[7] In about 723,[7] Bede wrote a longer work on the same subject, On the Reckoning of Time, which was influential throughout the Middle Ages.[122] He also wrote several shorter letters and essays discussing specific aspects of computus.

On the Reckoning of Time (De temporum ratione) included an introduction to the traditional ancient and medieval view of the cosmos, including an explanation of how the spherical Earth influenced the changing length of daylight, of how the seasonal motion of the Sun and Moon influenced the changing appearance of the new moon at evening twilight.[123] Bede also records the effect of the moon on tides. He shows that the twice-daily timing of tides is related to the Moon and that the lunar monthly cycle of spring and neap tides is also related to the Moon's position.[124] He goes on to note that the times of tides vary along the same coast and that the water movements cause low tide at one place when there is high tide elsewhere.[125] Since the focus of his book was the computus, Bede gave instructions for computing the date of Easter from the date of the Paschal full moon, for calculating the motion of the Sun and Moon through the zodiac, and for many other calculations related to the calendar. He gives some information about the months of the Anglo-Saxon calendar.[126]

Any codex of Bede's Easter table is normally found together with a codex of his De temporum ratione. His Easter table, being an exact extension of Dionysius Exiguus' Paschal table and covering the time interval AD 532–1063,[127] contains a 532-year Paschal cycle based on the so-called classical Alexandrian 19-year lunar cycle,[128] being the close variant of bishop Theophilus' 19-year lunar cycle proposed by Annianus and adopted by bishop Cyril of Alexandria around AD 425.[129] The ultimate similar (but rather different) predecessor of this Metonic 19-year lunar cycle is the one invented by Anatolius around AD 260.[130]

For calendric purposes, Bede made a new calculation of the age of the world since the creation, which he dated as 3952 BC. Because of his innovations in computing the age of the world, he was accused of heresy at the table of Bishop Wilfrid, his chronology being contrary to accepted calculations. Once informed of the accusations of these "lewd rustics", Bede refuted them in his Letter to Plegwin.[131]

In addition to these works on astronomical timekeeping, he also wrote De natura rerum, or On the Nature of Things, modelled in part after the work of the same title by Isidore of Seville.[132] His works were so influential that late in the ninth century Notker the Stammerer, a monk of the Monastery of St Gall in Switzerland, wrote that "God, the orderer of natures, who raised the Sun from the East on the fourth day of Creation, in the sixth day of the world has made Bede rise from the West as a new Sun to illuminate the whole Earth".[133]

Educational works

Bede wrote some works designed to help teach grammar in the abbey school. One of these was De arte metrica, a discussion of the composition of Latin verse, drawing on previous grammarians' work. It was based on Donatus's De pedibus and Servius's De finalibus and used examples from Christian poets as well as Virgil. It became a standard text for the teaching of Latin verse during the next few centuries. Bede dedicated this work to Cuthbert, apparently a student, for he is named "beloved son" in the dedication, and Bede says "I have laboured to educate you in divine letters and ecclesiastical statutes."[134] De orthographia is a work on orthography, designed to help a medieval reader of Latin with unfamiliar abbreviations and words from classical Latin works. Although it could serve as a textbook, it appears to have been mainly intended as a reference work. The date of composition for both of these works is unknown.[135]

De schematibus et tropis sacrae scripturae discusses the Bible's use of rhetoric.[7] Bede was familiar with pagan authors such as Virgil, but it was not considered appropriate to teach biblical grammar from such texts, and Bede argues for the superiority of Christian texts in understanding Christian literature.[7][136] Similarly, his text on poetic metre uses only Christian poetry for examples.[7]

Latin poetry

A number of poems have been attributed to Bede. His poetic output has been systematically surveyed and edited by Michael Lapidge, who concluded that the following works belong to Bede: the Versus de die iudicii ("verses on the day of Judgement", found complete in 33 manuscripts and fragmentarily in 10); the metrical Vita Sancti Cudbercti ("Life of St Cuthbert"); and two collections of verse mentioned in the Historia ecclesiastica V.24.2. Bede names the first of these collections as "librum epigrammatum heroico metro siue elegiaco" ("a book of epigrams in the heroic or elegiac metre"), and much of its content has been reconstructed by Lapidge from scattered attestations under the title Liber epigrammatum. The second is named as "liber hymnorum diuerso metro siue rythmo" ("a book of hymns, diverse in metre or rhythm"); this has been reconstructed by Lapidge as containing ten liturgical hymns, one paraliturgical hymn (for the Feast of St Æthelthryth), and four other hymn-like compositions.[137]

Vernacular poetry

According to his disciple Cuthbert, Bede was doctus in nostris carminibus ("learned in our songs"). Cuthbert's letter on Bede's death, the Epistola Cuthberti de obitu Bedae, moreover, commonly is understood to indicate that Bede composed a five-line vernacular poem known to modern scholars as Bede's Death Song

And he used to repeat that sentence from St Paul "It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God," and many other verses of Scripture, urging us thereby to awake from the slumber of the soul by thinking in good time of our last hour. And in our own language—for he was familiar with English poetry—speaking of the soul's dread departure from the body:

Fore ðæm nedfere nænig wiorðe

ðonc snottora ðon him ðearf siæ

to ymbhycgenne ær his hinionge

hwæt his gastæ godes oððe yfles

æfter deað dæge doemed wiorðe.[138]Facing that enforced journey, no man can be

More prudent than he has good call to be,

If he consider, before his going hence,

What for his spirit of good hap or of evil

After his day of death shall be determined.

As Opland notes, however, it is not entirely clear that Cuthbert is attributing this text to Bede: most manuscripts of the latter do not use a finite verb to describe Bede's presentation of the song, and the theme was relatively common in Old English and Anglo-Latin literature. The fact that Cuthbert's description places the performance of the Old English poem in the context of a series of quoted passages from Sacred Scripture might be taken as evidence simply that Bede also cited analogous vernacular texts.[139]

On the other hand, the inclusion of the Old English text of the poem in Cuthbert's Latin letter, the observation that Bede "was learned in our song," and the fact that Bede composed a Latin poem on the same subject all point to the possibility of his having written it. By citing the poem directly, Cuthbert seems to imply that its particular wording was somehow important, either since it was a vernacular poem endorsed by a scholar who evidently frowned upon secular entertainment[140] or because it is a direct quotation of Bede's last original composition.[141]

Veneration

There is no evidence for cult being paid to Bede in England in the 8th century. One reason for this may be that he died on the feast day of Augustine of Canterbury. Later, when he was venerated in England, he was either commemorated after Augustine on 26 May, or his feast was moved to 27 May. However, he was venerated outside England, mainly through the efforts of Boniface and Alcuin, both of whom promoted the cult on the continent. Boniface wrote repeatedly back to England during his missionary efforts, requesting copies of Bede's theological works.[142]

Alcuin, who was taught at the school set up in York by Bede's pupil Ecgbert, praised Bede as an example for monks to follow and was instrumental in disseminating Bede's works to all of Alcuin's friends.[142] Bede's cult became prominent in England during the 10th-century revival of monasticism and by the 14th century had spread to many of the cathedrals of England. Wulfstan, Bishop of Worcester was a particular devotee of Bede's, dedicating a church to him in 1062, which was Wulfstan's first undertaking after his consecration as bishop.[143]

His body was 'translated' (the ecclesiastical term for relocation of relics) from Jarrow to Durham Cathedral around 1020, where it was placed in the same tomb with St Cuthbert. Later Bede's remains were moved to a shrine in the Galilee Chapel at Durham Cathedral in 1370. The shrine was destroyed during the English Reformation, but the bones were reburied in the chapel. In 1831 the bones were dug up and then reburied in a new tomb, which is still there.[144] Other relics were claimed by York, Glastonbury[13] and Fulda.[145]

His scholarship and importance to Catholicism were recognised in 1899 when the Vatican declared him a Doctor of the Church.[7][146] He is the only Englishman named a Doctor of the Church.[41][92] He is also the only Englishman in Dante's Paradise (Paradiso X.130), mentioned among theologians and doctors of the church in the same canto as Isidore of Seville and the Scot Richard of St Victor.

His feast day was included in the General Roman Calendar in 1899, for celebration on 27 May rather than on his date of death, 26 May, which was then the feast day of St Augustine of Canterbury. He is venerated in the Catholic Church,[92] in the Church of England[147] and in the Episcopal Church (United States)[148] on 25 May, and in the Eastern Orthodox Church, with a feast day on 27 May (Βεδέα του Ομολογητού).[149]

Bede became known as Venerable Bede (Latin: Beda Venerabilis) by the 9th century[150] because of his holiness,[41] but this was not linked to consideration for sainthood by the Catholic Church. According to a legend, the epithet was miraculously supplied by angels, thus completing his unfinished epitaph.[151][i] It is first utilised in connection with Bede in the 9th century, where Bede was grouped with others who were called "venerable" at two ecclesiastical councils held at Aachen in 816 and 836. Paul the Deacon then referred to him as venerable consistently. By the 11th and 12th century, it had become commonplace.[11]

Modern legacy

Bede's reputation as a historian, based mostly on the Historia Ecclesiastica, remains strong.[96][97] Thomas Carlyle called him "the greatest historical writer since Herodotus".[152] Walter Goffart says of Bede that he "holds a privileged and unrivalled place among first historians of Christian Europe".[94] He is patron of Beda College in Rome which prepares older men for the Roman Catholic priesthood. His life and work have been celebrated with the annual Jarrow Lecture, held at St Paul's Church, Jarrow, since 1958.[153]

Bede has been described as a progressive scholar, who made Latin and Greek teachings accessible to his fellow Anglo-Saxons.[154]

Jarrow Hall (formerly Bede's World), in Jarrow, is a museum that celebrates the history of Bede and other parts of English heritage, on the site where he lived.

Bede Metro station, part of the Tyne and Wear Metro light rail network, is named after him.[155]

See also

- List of manuscripts of Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica

- List of works by Bede

- Medieval ecclesiastic historiography

Catholic Church portal

Catholic Church portal

Notes

- ^ Anselm of Canterbury, also a Doctor of the Church, was originally from Italy.

- ^ Bede's words are "Ex quo tempore accepti presbyteratus usque ad annum aetatis meae LVIIII ..."; which means "From the time I became a priest until the fifty-ninth year of my life I have made it my business ... to make brief extracts from the works of the venerable fathers on the holy Scriptures ..."[8][9] Other, less plausible, interpretations of this passage have been suggested—for example that it means Bede stopped writing about scripture in his fifty-ninth year.[10]

- ^ Cuthbert is probably the same person as the later abbot of Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, but this is not entirely certain.[11]

- ^ Isidore of Seville lists six orders below a deacon, but these orders need not have existed at Monkwearmouth.[9]

- ^ The key phrase is per linguae curationem, which is variously translated as "how his tongue was healed", "[a] canker on the tongue", or, following a different interpretation of curationem, "the guidance of my tongue".[32]

- ^ The letter itself is in Bedae Opera de Temporibus edited by C. W. Jones, pp. 307–315

- ^ Laistner 1935, pp. 263–266 provides a list of works definitely or tentatively identified as in Bede's library.

- ^ Laistner 1935, pp. 263–266 provides a list of works definitely or tentatively identified as in Bede's library.

- ^ The legend tells that the monk engraving the tomb was stuck for an epithet. He had got as far as Hac sunt in fossa Bedae ... ossa ("Here in this grave are the bones of ... Bede") before heading off to bed. In the morning an angel had inserted the word venerabilis.

References

- ^ a b c d e f Ray 2001, pp. 57–59

- ^ Hutchinson-Hall, John (Ellsworth). Orthodox Saints of the British Isles. Vol II (St. Eadfrith Press, 2014) p. 133

- ^ a b c d e f Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. xxv–xxvi

- ^ a b c d e f g Ward 2001, pp. 57–64

- ^ Brooks 2006, p. 5

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, p. xix

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Campbell 2004

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 566–567

- ^ a b c Blair 1990, p. 253

- ^ Whiting 1935, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Higham 2006, pp. 9–10

- ^ Bede, Ecclesiastical History, V.24, p. 329.

- ^ a b c Farmer 2004, pp. 47–48

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. xix–xx

- ^ Blair 1990, p. 4

- ^ J. Insley, "Portesmutha" in: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde vol. 23, Walter de Gruyter (2003), 291.

- ^ Förstemann, Altdeutsches Namenbuch s.v. BUD (289) connects the Old High German short name Bodo (variants Boto, Boddo, Potho, Boda, Puoto etc.) as from the same verbal root.

- ^ a b Higham 2006, pp. 8–9

- ^ Swanton 1998, pp. 14–15

- ^ Kendall 2010, p. 101; Rowley 2017, p. 258

- ^ a b Blair 1990, p. 178

- ^ Blair 1990, p. 241

- ^ a b c Colgrave & Mynors 1969, p. xx

- ^ Plummer, Bedae Opera Historica, vol. I, p. xii.

- ^ Blair 1990, p. 181

- ^ a b c d e Blair 1990, p. 5

- ^ Blair 1990, p. 234

- ^ "Classical and Medieval MSS". Bodleian Library. Retrieved 30 December 2010.

- ^ A few pages from another copy are held by the British Museum. Farmer 1978, p. 20

- ^ Ray 2001, p. 57

- ^ Whiting 1935, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Whitelock 1976, p. 21.

- ^ a b Blair 1990, p. 267

- ^ Bede 1985, p. 38.

- ^ Goffart, Narrators p. 322

- ^ a b Blair 1990, p. 305

- ^ Higham 2006, p. 15

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, p. 556n

- ^ Plummer, Bedae Opera Historica, vol. II, p. 3.

- ^ Firth, Ashley (19 April 2022). "Who Was Bede?". MancHistorian. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ a b c d Fr. Paolo O. Pirlo, SHMI (1997). "St. Venerable Bede". My First Book of Saints. Sons of Holy Mary Immaculate – Quality Catholic Publications. p. 104. ISBN 978-971-91595-4-4.

- ^ a b Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 580–587

- ^ Blair 1990, p. 307

- ^ Donald Scragg, "Bede's Death Song", in Lapidge, Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 59.

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 580–581n

- ^ "St. Gallen Stiftsbibliothek Cod. Sang. 254. Jerome, Commentary on the Old Testament book of Isaiah. Includes the most authentic version of the Old English "Death Song" by the Venerable Bede". Europeana Regia. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ^ a b Quoted in Ward 1990, p. 57

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 57

- ^ Holder (trans.), Bede: On the Tabernacle, (Liverpool: Liverpool Univ. Pr., 1994), pp. xvii–xx.

- ^ McClure and Collins, The Ecclesiastical History, pp. xviii–xix.

- ^ Goffart 1988, pp. 242–243

- ^ Frantzen, Allan J. (1983). The Literature of Penance in Anglo-Saxon England (1st ed.). New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0813509556.

- ^ a b Farmer 1978, p. 21

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ a b Farmer 1978, p. 22

- ^ a b c Farmer 1978, p. 31

- ^ Farmer 1978, pp. 31–32

- ^ Abels 1983, pp. 1–2

- ^ a b Farmer 1978, p. 32

- ^ Bede, "Preface", Historia Ecclesiastica, p. 41.

- ^ Cramp, "Monkwearmouth (or Wearmouth) and Jarrow", pp. 325–326.

- ^ Michael Lapidge, "Libraries", in Lapidge, Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 286–287.

- ^ a b c d Farmer 1978, p. 25

- ^ a b Campbell, "Bede", in Dorey, Latin Historians, p. 162.

- ^ Campbell, "Bede", in Dorey, Latin Historians, p. 163.

- ^ Lapidge, "Gildas", p. 204.

- ^ Meyvaert 1996, p. 831

- ^ Meyvaert 1996, p. 843

- ^ Plummer, Bedae Opera Historic, vol. I, p. xxiv.

- ^ a b Campbell, "Bede", in Dorey, Latin Historians, p. 164.

- ^ Keynes, "Nothhelm", pp. 335 336.

- ^ a b c Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica, Preface, p. 42.

- ^ Goffart 1988, pp. 296–307

- ^ Brooks 2006, pp. 7–10

- ^ Brooks 2006, pp. 12–14

- ^ Farmer 1978, p. 26

- ^ a b Farmer 1978, p. 27

- ^ Lapidge 2005, p. 323

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. xxxvii–xxxviii

- ^ Plummer, Bedae Opera Historica, vol. I, pp. liii–liv.

- ^ a b Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. xxx–xxxi

- ^ Higham 2013, pp. 476–493.

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. xxxiv–xxxvi

- ^ Stenton 1971, pp. 8–9

- ^ Wallace-Hadrill 1988, p. xxxi

- ^ Yorke 2006, p. 119

- ^ Yorke 2006, pp. 21–22

- ^ Fleming 2011, p. 111

- ^ Yorke 2006, p. 118

- ^ a b Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. xviii–xix

- ^ Stenton 1971, p. 186

- ^ a b c d Wright 2008, pp. 4–5

- ^ Higham 2006, p. 21

- ^ a b Goffart 1988, p. 236

- ^ Goffart 1988, pp. 238–239

- ^ a b Stenton 1971, p. 187

- ^ a b Wormald 1999, p. 29

- ^ Higham 2006, p. 27

- ^ Higham 2006, p. 33

- ^ Behr 2000, pp. 25–52

- ^ Plummer, Bedae Opera Historica, vol. I, p. xlvii and note.

- ^ Cannon & Griffiths 1997, pp. 42–43

- ^ Wallis (trans.), The Reckoning of Time, pp. lxvii–lxxi, 157–237, 353–66

- ^ Goffart 1988, pp. 245–246

- ^ Brown 1987, p. 42

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 44

- ^ Meyvaert 1996, p. 827

- ^ a b Laistner 1935, pp. 237–262.

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 51

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 56

- ^ Ward 1990, pp. 58–59

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 60

- ^ Loyn 1962, p. 270

- ^ Bühler, Curt F. "A Lollard Tract: on Translating the Bible Into English". Medium Ævum, vol. 7, no. 3, 1938, p. 181. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 67

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 68

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 72

- ^ Obermair 2010, pp. 45–57

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 74

- ^ Thacker 1998, p. 80

- ^ Brown 1987, p. 37

- ^ Brown 1987, pp. 38–41

- ^ Bede 2004, pp. 82–85, 307–312

- ^ Bede 2004, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Bede 2004, p. 65.

- ^ Bede 2004, pp. 53–54, 285–287; see also [1]

- ^ Zuidhoek (2019) 103-120

- ^ Zuidhoek (2019) 70

- ^ Mosshammer (2008) 190-203

- ^ Declercq (2000) 65-66

- ^ Bede 2004, pp. xxx, 405–415

- ^ Brown 1987, p. 36

- ^ Bede 2004, p. lxxxv

- ^ Brown 1987, pp. 31–32

- ^ Brown 1987, pp. 35–36

- ^ Colgrave gives the example of Desiderius of Vienne, who was reprimanded by Gregory the Great for using "heathen" authors in his teaching.

- ^ Joseph P. McGowan, review of Michael Lapidge, ed. and tr. Bede's Latin Poetry. Oxford Medieval Texts. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2019. Pp. xvi, 605. $135.00. ISBN 978-0-19-924277-1, in The Medieval Review (4 April 2021).

- ^ Colgrave & Mynors 1969, pp. 580–583

- ^ Opland 1980, pp. 140–141

- ^ McCready 1994, pp. 14–19

- ^ Opland 1980, p. 14

- ^ a b Ward 1990, pp. 136–138

- ^ Ward 1990, p. 139

- ^ Wright 2008, p. 4 (caption)

- ^ Higham 2006, p. 24

- ^ "Acta Sanctae Sedis" (PDF) (in Latin). Vatican. 1899. pp. 358–359. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 June 2015.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018. Church Publishing, Inc. 17 December 2019. ISBN 978-1-64065-235-4.

- ^ "Venerable Bede, the Church Historian". www.oca.org.

- ^ Wright 2008, p. 3

- ^ "Catholic Encyclopedia: The Venerable Bede". New Advent.

- ^ Adrian, Arthur A. "Dean Stanley's Report of Conversations with Carlyle". Victorian Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, Indiana University Press, 1957, pp. 72–74.

- ^ "The jarrow lecture". stpaulschurchjarrow.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2008. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ "How Sunderland became a poster child for Brexit". 8 July 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Bede Metro Station | Co-Curate". co-curate.ncl.ac.uk. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

Sources

Primary sources

- Bede (c. 860). "St. Gallen Stiftsbibliothek Cod. Sang. 254. Jerome, Commentary on the Old Testament book of Isaiah. Includes the most authentic version of the Old English "Death Song" by the Venerable Bede". Europeana Regia. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- ——— (1896). Plummer, C (ed.). Hist. eccl. · Venerabilis Baedae opera historica. Vol. 2 vols.

- ——— (1969). Colgrave, Bertram; Mynors, R.A.B. (eds.). Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822202-6. (Parallel Latin text and English translation with English notes.)

- ——— (1985). David Hurst (ed.). The Commentary on the Seven Catholic Epistles of Bede the Venerable. Cistercian Publications. ISBN 9780879078829.

- ——— (1991). D. H. Farmer (ed.). Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Revised by R.E. Latham. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044565-7.

- ——— (1991). Kendall, Calvin B. (ed.). Libri II De Arte Metrica et De Schematibus et Tropis. Saarbrücken: AQ-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-922441-60-1.

- ——— (1994). McClure, Judith; Collins, Roger (eds.). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-283866-7.

- ——— (1943). Jones, C.W. (ed.). Bedae Opera de Temporibus. Cambridge, MA: Mediaeval Academy of America.

- ——— (2004). Bede: The Reckoning of Time. Translated by Wallis, Faith. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-693-1.

- ——— (2011). On the Song of Songs and selected writings. The Classics of Western Spirituality. Translated by Holder, Arthur G. New York: Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4700-7. (contains translations of On the Song of Songs, Homilies on the Gospels and selections from the Ecclesiastical history of the English people).

- The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Translated by Swanton, Michael James. New York: Routledge. 1998. ISBN 978-0-415-92129-9.

Secondary sources

- Abels, Richard (1983). "The Council of Whitby: A Study in Early Anglo-Saxon Politics". Journal of British Studies. 23 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1086/385808. JSTOR 175617. S2CID 144462900.

- Behr, Charlotte (2000). "The Origins of Kingship in Early Medieval Kent". Early Medieval Europe. 9 (1): 25–52. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00058. S2CID 162301448.

- Blair, Peter Hunter (1990). The World of Bede (Reprint of 1970 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39819-0.

- Brooks, Nicholas (2006). "From British to English Christianity: Deconstructing Bede's Interpretation of the Conversion". In Howe, Nicholas; Karkov, Catherine (eds.). Conversion and Colonization in Anglo-Saxon England. Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-0-86698-363-1.

- Brown, George Hardin (1987). Bede, the Venerable. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 978-0-8057-6940-1.

- ——— (1999). "Royal and Ecclesiastical rivalries in Bede's History". Renascence. 51 (1): 19–33. doi:10.5840/renascence19995213.

- Campbell, J. (23 September 2004). "Bede (673/4–735)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1922. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Cannon, John; Griffiths, Ralph (1997). The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Monarchy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822786-1.

- Chadwick, Henry (1995). "Theodore, the English Church, and the Monothelete Controversy". In Lapidge, Michael (ed.). Archbishop Theodore. Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England #11. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–95. ISBN 978-0-521-48077-2.

- Colgrave, Bertram; Mynors, R.A.B. (1969). "Introduction". Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822202-6.

- Declercq, Georges (2000). Anno Domini (The Origins of the Christian Era). Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 9782503510507.

- Dorey, T.A. (1966). Latin Historians. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Englisch, Brigitte (1994). Die Artes liberales im frühen Mittelalter (5.–9. Jahrhundert). Das Quadrivium und der Komputus als Indikatoren für Kontinuität und Erneuerung der exakten Wissenschaften zwischen Antike und Mittelalter. Stuttgart: Sudhoffs Archiv, Beihefte 33. pp. 71–80 (biography), pp. 242–246 (De natura rerum), pp. 280–370 (computus).

- Farmer, David Hugh (1978). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-282038-9.

- ——— (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860949-0.

- Fleming, Robin (2011). Britain after Rome: The Fall and the Rise, 400 to 1070. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014823-7.

- Goffart, Walter A. (1988). The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550–800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-05514-5.

- Higham, N.J. (2006). (Re-)Reading Bede: The Historia Ecclesiastica in Context. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-35368-7.

- Higham, N.J. (2013). "Bede's Agenda in Book IV of the 'Ecclesiastical History of the English People': A Tricky Matter of Advising the King". Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 64 (3): 476–493. doi:10.1017/s0022046913000523. S2CID 159608095.

- Kendall, Calvin B. (2010). "Bede and Education". In DeGregorio, Scott (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Bede. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–112. ISBN 9781139825429.

- Laistner, M.L.W. (1935). "The Library of the Venerable Bede". In A. Hamilton Thompson (ed.). Bede: His Life, Times and Writings: Essays in Commemoration of the Twelfth Century of his Death. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN 9780198223177.

- Lapidge, Michael (2005). "Poeticism in Pre-Conquest Anglo-Latin Prose". In Reinhardt, Tobias; et al. (eds.). Aspects of the Language of Latin Prose. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-726332-7.

- Loyn, H.R. (1962). Anglo-Saxon England and the Norman Conquest. Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-48232-6.

- McCready, William D. (1994). Miracles and the Venerable Bede: Studies and Texts. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies #118. Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. ISBN 978-0-88844-118-8.

- Mayr-Harting, Henry (1991). The Coming of Christianity to Anglo-Saxon England. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-00769-4.

- Meyvaert, Paul (1996). "Bede, Cassiodorus, and the Codex Amiatinus". Speculum. 71 (4). Medieval Academy of America: 827–883. doi:10.2307/2865722. JSTOR 2865722. S2CID 162009695.

- Mosshammer, Alden A. (2008). The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199543120.

- Obermair, Hannes (2010). "Novit iustus animas. Ein Bozner Blatt aus Bedas Kommentar der Sprüche Salomos" (PDF). Concilium Medii Aevi. 31. Edition Ruprecht: 45–57. ISSN 1437-904X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- Opland, Jeff (1980). Anglo-Saxon Oral Poetry: A Study of the Traditions. New Haven and London: Yale U.P. ISBN 978-0-300-02426-5.

- Ray, Roger (2001). "Bede". In Lapidge, Michael; et al. (eds.). Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Malden, MA: Blackwell. pp. 57–59. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Rowley, Sharon M. (2017). "Bede". In Echard, Sian; Rouse, Robert (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Medieval Literature in Britain. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 257–264. ISBN 978-1118396988.

- Stenton, F.M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England (Third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280139-5.

- Thacker, Alan (1998). "Memorializing Gregory the Great: The Origin and Transmission of a Papal Cult in the 7th and early 8th centuries". Early Medieval Europe. 7 (1): 59–84. doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00018. S2CID 161546509.

- Thompson, A. Hamilton (1969). Bede: His Life, Times and Writings: Essays in Commemoration of the Twelfth Century of his Death. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tyler, Damian (April 2007). "Reluctant Kings and Christian Conversion in Seventh-Century England". History. 92 (306): 144–161. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.2007.00389.x.

- Wallace-Hadrill, J.M. (1988). Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People: A Historical Commentary. Oxford Medieval Texts. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-822269-9.

- Ward, Benedicta (1990). The Venerable Bede. Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8192-1494-2.

- ——— (2001). "Bede the Theologian". In Evans, G.R. (ed.). The Medieval Theologians: An Introduction to Theology in the Medieval Period. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 57–64. ISBN 978-0-631-21203-4.

- Whiting, C.E. (1935). "The Life of the Venerable Bede". In A. Hamilton Thompson (ed.). Bede: His Life, Times and Writings: Essays in Commemoration of the Twelfth Century of his Death. Oxford: Clarendon. ISBN 9780198223177.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1976). "Bede and his Teachers and Friends". In Gerald Bonner (ed.). Famulus Christi: Essays in Commemoration of the Thirteenth Centenary of the Birth of the Venerable Bede. SPCK. ISBN 9780281029495.

- Wormald, Patrick (1999). The Making of English Law: King Alfred to the Twelfth Century. Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-13496-1.

- Wright, J. Robert (2008). A Companion to Bede: A Reader's Commentary on The Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6309-6.

- Yorke, Barbara (2006). The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-77292-2.

- Zuidhoek, Jan (2019). Reconstructing Metonic 19-year Lunar Cycles (on the basis of NASA's Six Millennium Catalog of Phases of the Moon). Zwolle: JZ. ISBN 978-9090324678.

Further reading

- Story, Joanna; Bailey, Richard (2015). "The Skull of Bede". The Antiquaries Journal. 95: 325–350. doi:10.1017/s0003581515000244. S2CID 163360680.

External links

- Dickinson College Commentaries: Historia Ecclēsiastica

- Works by Bede at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Bede at the Internet Archive

- Works by Bede at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Bede's World: the museum of early medieval Northumbria at Jarrow

- The Venerable Bede from In Our Time (BBC Radio 4)

- Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Books 1–5, L.C. Jane's 1903 Temple Classics translation. From the Internet Medieval Sourcebook.

- Bede's Ecclesiastical History and the Continuation of Bede (pdf), at CCEL, edited & translated by A.M. Sellar.

- Saint Bede, complete works, in Latin, with historical works also in English at The Online Library of Liberty

- Dionysius Exiguus' Paschal table