Royal Indian Navy mutiny

| Royal Indian Navy rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

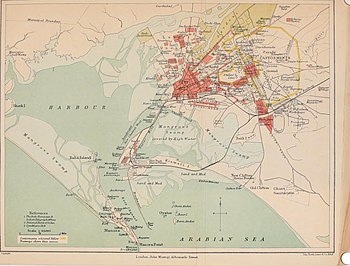

HMIS Hindustan near the shore. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| No centralised command |

| ||||||

The Royal Indian Navy mutiny was a failed insurrection of Indian naval ratings, soldiers, police personnel and civilians against the British government in India in February 1946. From the initial flashpoint in Bombay (now Mumbai), the revolt spread and found support throughout British India, from Karachi to Calcutta (now Kolkata), and ultimately came to involve over 10,000 sailors in 56 ships and shore establishments. The mutiny failed to turn into a revolution because sailors were asked to surrender after the British authorities had assembled superior forces to suppress the mutiny.[1][2]

The mutiny ended with the surrender of revolting RIN sailors to British authorities. The Indian National Congress and the Muslim League convinced Indian sailors to surrender and condemned the mutiny, realising the political and military risks of unrest of this nature on the eve of independence. The leaders of the Congress were of the view that their idea of a peaceful culmination to a freedom struggle and smooth transfer of power would have been lost if an armed revolt succeeded with undesirable consequences.[3] The Communist Party of India was the only nation–wide political organisation that supported the rebellion. The British authorities had later branded the Naval Mutiny as a "larger communist conspiracy raging from the Middle East to the Far East against the British crown".

The RIN Revolt started as a strike by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 18 February in protest against general conditions. The immediate issues of the revolt were living conditions and food. By dusk on 19 February, a Naval Central Strike committee was elected. The strike found some support amongst the Indian population, though not their political leadership who saw the dangers of mutiny on the eve of Independence. The actions of the mutineers were supported by demonstrations which included a one–day general strike in Bombay. The strike spread to other cities, and was joined by elements of the Royal Indian Air Force and local police forces.

Indian Naval personnel began calling themselves the "Indian National Navy" and offered left–handed salutes to British officers. At some places, NCOs in the British Indian Army ignored and defied orders from British superiors. In Madras and Poona (now Pune), the British garrisons had to face some unrest within the ranks of the Indian Army. Widespread rioting took place from Karachi to Calcutta. Notably, the revolting ships hoisted three flags tied together – those of the Congress, Muslim League, and the Red Flag of the Communist Party of India (CPI), signifying the unity and downplaying of communal issues among the mutineers.

The revolt was called off following a meeting between the President of the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC), M. S. Khan, and Vallab Bhai Patel of the Congress with a guarantee that none would be persecuted.[4] Contingents of the naval ratings were arrested and imprisoned in camps with distressing conditions over the following months,[5] and the condition of surrender which shielded them from persecution. Patel, who had been sent to Bombay to settle the crisis, issued a statement calling on the strikers to end their action, which was later echoed by a statement issued in Calcutta by Muhammad Ali Jinnah on behalf of the Muslim League. Under these considerable pressures, the strikers gave way. Arrests were then made, followed by courts martial and the dismissal of 476 sailors from the Royal Indian Navy. None of those dismissed were reinstated into either the Indian or Pakistani navies after independence.

Background

During the Second World War, the Royal Indian Navy (RIN) had rapidly expanded from a small naval force composed of sloops to become a full–fledged navy.[6] The expansion occurred in an ad hoc basis as operational requirements changed over the course of the war, the naval headquarters was moved from Bombay to New Delhi during this period, the navy acquired a varied assortment of warships and landing crafts, and the naval infrastructure in British India was expanded with improved dockyards, new training facilities and other support infrastructure.[7] The RIN played an instrumental role in halting the progress of Japanese forces in the Indian Ocean Theatre. The force was involved in escorting allied convoys in the Indian Ocean, defending the Indian shoreline against naval invasions and supporting allied military operations through coastlines and rivers during the Burma Campaign.[6]

Due to the war, recruitments began occurring beyond the confines of the "martial races" composed of demographics who were politically segregated.[8] The ratings were composed of a diverse group, from different regions and religions, mostly from rural backgrounds. Some of them had not even physically encountered Britons before the recruitment. Exponential rises in the price of goods, famines and other economic difficulties eventually forced many of them to join the expanding armed forces of the British Raj. In a period of 4 to 6 years, the recruits underwent a transformation in their mindset.[9] They were exposed to developments from around the world.[8]

In 1945, it was ten times larger than its size in 1939. Between 1942 and 1945, the CPI leaders helped in carrying out mass recruitment of Indians especially communist activists into the British Indian Army and RIN for war efforts against Nazi Germany. However once the war was over, the newly recruited men turned against the British government.

Demobilisation

The demobilisation of the Royal Indian Navy began once the war with Japan ended. Leased ships were paid off, a number of shore establishments were closed and the sailors were concentrated into select establishments for their release from service. Much of the concentration occurred in the naval establishments at Bombay, which served as the primary base for the RIN and hence became over crowded with bored and dissatisfied personnel awaiting their release.[6] The dissatisfaction among the Indian personnel came from a variety of causes such as dismal living conditions, arbitrary treatment, inadequate pay and a perception of an uncaring senior leadership. Despite the wartime expansion, the officer staff of the formed remained predominantly white and the navy was noted to be the most conservative in terms of number of Indian officers. The concentration of the personnel and grievances in its ranks combined with tense interracial relations and aspirations to end British rule in India led to a volatile situation in the navy.[10]

Unlike the close relationship between British Army and the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy was not privy to such a relationship with the Royal Navy. However the war had brought the two closer together under the leadership of the British High Command and due to temporary transfers between the two navies.[11] The British naval circles were prevalent with perceptions of lack of competency among Indians, opposition to the independence movement and assumptions of continued British presence in India.[12] John Henry Godfrey was the commanding officer of the RIN and had overseen its transformation from a small coastal defense fleet to a regional navy. In the post war period, he intended to preserve its status as a regional navy and had the vision for the RIN to serve as in instrument of British interests in the Indian Ocean. Operating under this vision, Godfrey proposed the acquisition of new warships from the British Admiralty and maintained that British officers would be necessary for the fleet to continue functioning as Indian officers lacked the required expertise and training.[11]

Indian National Army trials

The INA trials, the stories of Subhas Chandra Bose ("Netaji"), as well as the stories of INA's fight during the Siege of Imphal and in Burma were seeping into the glaring public–eye at the time. These, received through the wireless sets and the media, fed discontent and ultimately inspired the sailors to strike. After the Second World War, three officers of the Indian National Army (INA), General Shah Nawaz Khan, Colonel Prem Sahgal and Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon were put on trial at the Red Fort in Delhi for "waging war against the King Emperor", i.e., the Emperor of India.

According to the Home Department of the Raj, the Congress advocacy during the trials, their election campaign for the advisory council and the highlighting of excesses during the Quit India Movement contained inflammatory speeches and had created a volatile atmosphere. There were several upsurges between November 1945 and February 1946. In a September 1945, All India Congress Committee meeting, the party had taken the stand that in case of any confrontations, negotiation and settlement must be the way forward.[8]

Calcutta in particular experienced frequent instances of civil unrest in opposition to the trials,[13] and eventually led to the popular support emerging in favor of the revolutionary vision of an independent India that was advocated by the Communist Party of India.[14]

Unrest in the British forces in India

"Provided they do their duty, armed insurrection in India would not be an insoluble problem. If however the Indian Army went the other way the picture would be very different."

Between 1943 and 1945, the Royal Indian Navy suffered nine mutinies on board various individual ships.[16]

In early February 1946, mutinies broke out in the Indian Pioneers unit stationed in Calcutta, Bengal Province and later at a signals training center at the air base in Jubbulpore, Central Provinces and Berar.[16] According to Francis Tuker, the commanding officer of the Eastern Command, the dissatisfaction against British colonial rule was rapidly growing within the bureaucracy and the police force as well as in the armed forces itself.[17]

HMIS Talwar

HMIS Talwar was a shore establishment,[18] with a signals school at Colaba, Bombay.[19] Following the end of the war, the establishment was among the locations in Bombay where a large number of ratings were deployed.[6] Around 1,000 communications operators were residing at the establishment,[20] most of the whom consisted of lower–middle class and middle–class people with matriculation or college education as opposed to general seamen who were primarily from the peasantry.[21] In late 1945, upon reassignment, around 20 operators along with a dozen sympathisers frustrated with racial discrimination faced by them during their period of service, formed a secretive group under the self designation of Azad Hind (transl. Free Indians) and began hatching conspiracies to undermine their senior officers.[22]

The first incident occurred on 1 December 1945, when RIN Commanders had intended to open up the establishment to the public; in the morning the group vandalised the premises by littering the parade ground with burnt flags and bunting, prominently displaying brooms and buckets at the tower and painting slogans such as "Quit India, Down with British Raj", and "Victory to Gandhi and Nehru", across various walls of the establishment.[23] The senior officers cleaned up the premises before the public arrived without further action. The weak response emboldened the conspirators who continued on with similar activities over the course of the following months.[22]

The response was a result of correspondences issued by the Commander–in–Chief Sir Claude Auchinleck informing officers to maintain a degree of tolerance for a smooth transition in case of Indian Independence such that British interests are secured by maintaining good relations. Unable to catch the conspirators and restricted from taking strict action against their underlings, the command at HMIS Talwar resorted to increasing the pace of demobilization in the hopes that the troublemakers would be pushed out of the force during the process. As a result, the group shrunk in size but the remaining ones remained enthused for more nationalistic activities.[24]

On 2 February 1946, Auchinleck himself was supposed to attend the establishment and the officers aware of the potential for vandalism had employed guards to prevent any large–scale action beforehand. Despite this, the group was able to add stickers and paint the walls of the podium from where the C–in–C was to receive the establishment's salute, featuring slogans such as "Quit India" and "Jai Hind". The vandalism was spotted before sunrise and Balai Chandra Dutt, a five–year veteran of the war, was caught while escaping the scene with stickers and glue in his hand.[25] Subsequently, his lockers were searched and communist and nationalist literature were found among its contents.[26][27] The material was considered to be seditious; Dutt was interrogated by five senior officers in quick succession including a rear-admiral, he claimed responsibility for all acts of vandalism and announced his status as a political prisoner.[28] He was imprisoned in solitary confinement for seventeen days,[9] while the acts themselves continued unabated following his imprisonment.[28]

On 8 February 1946, a number of naval ratings (enlisted personnel) were court martialed for insubordination,[16] and the commanding officer Frederick King reportedly indulged in racialist polemic along with the use of epithets such as "sons of bitches", "sons of coolies" and "junglies" to describe his Indian underlings.[18][27] Some of the naval ratings filed a formal complaints against the leadership style of the commanding officer.[10] On 17 February, a large number of ratings began refusing food and orders for military parades,[16] King had reportedly used the term "black bastards" to describe a group of sailors during the morning briefing.[10] By 18 February, the ratings at HMIS Sutlej, HMIS Jumna, and those at Castle and Fort Barracks in the Bombay Harbour followed suit and began refusing orders, in solidarity with the operators at HMIS Talwar.[29]

At 12:30, 18 February 1946, it was reported that all naval ratings below the rank of petty officer at HMIS Talwar were refusing commands from the CO.[30] Eventually, the ratings rebelled, seizing control of the shore establishment and expelling the officers. Over the course of the day, the ratings moved across the Bombay Harbour from ship to ship in an attempt to convince other ratings to join them in the mutiny.[31][32] In the meantime, B. C. Dutt had spent several days in solitary confinement and was allowed to return at the Talwar barracks before his expected dismissal from the force.[17] He would later come to be known one of the primary instigators of the mutiny.[27] Within a day, the mutiny had spread to 22 ships in the harbour and 12 other shore establishments in Bombay.[31][32] On the same day, the mutiny was also joined in by RIN operated wireless stations including those as distant as Aden and Bahrain; the mutineers at HMIS Talwar had used available wireless devices at the signals school to establish direct communications with them.[10]

Occupation of Bombay Harbour

On 19 February, the Flag Officer Commanding, Royal Indian Navy, Admiral John Henry Godfrey sent out a communication via the All India Radio, stating that the most stringent measures would be utilised to suppress their mutiny, including if necessary the destruction of the Navy itself.[33] Rear Admiral Arthur Rullion Rattray, second–in–command to the Royal Indian Navy,[34] and the commanding officer at the Bombay Harbour conducted an inspection in person which confirmed that the unrest was widespread and beyond his control.[10] Rattray insisted on a parley with the mutineers but Auchinleck and Godfrey were both opposed to the idea.[34] The events at HMIS Talwar had motivated sailors across Bombay and the Royal Indian Navy to join in by the prospects of a revolution to overthrow the British Raj and in solidarity with the grievances of their naval fraternity.[35]

Over the course of the day, many of the ratings moved into the city armed with hockey sticks and fire axes, causing traffic disruption and occasionally commandeering vehicles.[36] Motor launches seized at the harbour were paraded around and cheered on by crowds gathering at the piers.[36] Demonstrations and agitations broke out in the city,[37] gasoline was seized from passing trucks, tramway tracks outside the Prince of Wales Museum were set on fire,[36] the US Information Office was raided and the American flag located inside was pulled down and burned on the streets.[36][37]

On the morning of 20 February 1946, it was reported that Bombay Harbour, including all its ships and naval establishments had been overtaken by mutineers.[38] It encompassed 45 warships,[36][39] 10–12 shore establishments,[31][36] 11 auxiliary vessels and four flotillas,[39] overtaken by around 10,000 naval ratings.[36] The harbour facilities consisted of the Fort and Castle Barracks, the Central Communications Office which oversaw all signals traffic for naval communications in Bombay, the Colaba receiving station and hospital facilities of the Royal Indian Navy located nearby in Sewri. The warships included two destroyers HMIS Narbada and HMIS Jumna, two older warships HMIS Clive and HMIS Lawrence, one frigate HMIS Dhanush and four corvettes HMIS Gondwana (K348), HMIS Assam (K306), HMIS Mahratta (K395) and HMIS Sind (K274), among other ships such as gunboats and naval trawlers.[39]

The solitary exception to the mutiny at the Bombay Harbour was the frigate HMIS Shamsher,[40] a "test ship" with Indian officers. The commanding officer of HMIS Shamsher, Lieutenant Krishnan had created a diversionary signal and moved out of the harbour on 20:00, 18 February 1946. Despite protestations from his Sub–Lieutenant R. K. S. Ghandhi, Krishnan did not join the rebellion and was also able to prevent a mutiny from the ratings under his command, with an apparent "charismatic speech" where he used his Indian identity to maintain the chain of command.[41]

The rebellion also included shore establishments in the vicinity of Bombay; HMIS Machlimar at Versova, an anti–submarine training school was manned by 300 ratings, HMIS Hamla at Marvé which held the residence quarters of the landing craft wing of the RIN had been seized by 600 ratings, HMIS Kakauri, the demobilisation center in the city which was seized by over 1,400 ratings who were housed there. On Trombay Island, the Mahul wireless communications station and HMIS Cheetah, a second demobilisation center were also seized by mutineers. HMIS Akbar at Kolshet, a training facility for Special Services ratings which had the capacity of 3,000 trainees was seized by the 500 ratings who were residing within it premises. Two inland establishments, HMIS Shivaji in Lonavala was a mechanical training establishment was seized by 800 ratings and HMIS Feroze in the Malabar Hills, a reserve officer's training facility that had been converted into an officer's demobilisation center, was seized by 120 ratings.[42]

Strike Committee and the Charter of Demands

In the afternoon of 19 February, the mutineers at the Bombay Harbour had congregated at HMIS Talwar to elect the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC) as their representatives and formulate the Charter of Demands.[43][44] Warships and shore establishments became constituencies for the election of the committee from which individual representatives were elected to the committee. Most of the members of the committee remain unknown, and many of them were reportedly under 25.[43] Of those known, were the petty officer Madan Singh and signalman M. S. Khan, who were authorised by the committee to conduct informal talks.[44] The Charter of Demands was sent to the authorities and consisted of a mixture of political and service related demands.[19][44]

- Release of all Indian political prisoners;

- Release of all Indian National Army personnel unconditionally;

- Withdrawal of all Indian personnel from Indonesia and Egypt;

- Eviction of British nationals from India;

- Prosecution of the commanding officers and signal bosuns for mistreatment of crew;

- Release of all detained naval ratings;

- Demobilisation of the Royal Indian Navy ratings and officers, with haste;

- Equality in status with the Royal Navy regarding pay, family allowances and other facilities;

- Optimum quality of Indian food in the service;

- Removal of requirements for return of clothing kit after discharge from service;

- Improvement in standards of treatment by officers towards subordinates;

- Installation of Indian officers and supervisors.

On the warships and shore establishments, the British flags and naval ensigns were pulled down and the flags of the Indian National Congress, All–India Muslim League and the Communist Party of India were hoisted.[45] The Bombay committee of the Communist Party of India called a general strike which was supported by leaders from the Congress Socialist Party, a socialist caucus within the Indian National Congress. The provincial units of the Indian National Congress and the All India Muslim League however opposed the mutiny from the onset.[46] Disappointed and disgruntled with opposition from the national leadership towards the mutiny, the flags of the Congress and Muslim League were pulled down and only the red flags kept aloft.[45]

Intervention by the Southern Command

On 20 February 1946, the Naval Central Strike Committee had recommended some of the ratings to move into the city to garner popular support for their demands.[47] RIN trucks packed with naval ratings entered European–dominated commercial districts of Bombay shouting slogans to galvanize Indians, followed by instances of altercations between the mutineers and Europeans including servicemen.[38] Police personnel, students and labour organisations in the city went on sympathetic strikes in support of the mutineers.[47] The Royal Indian Air Force units also witnessed unrest in its base of operations in Bombay. The personnel including pilots refused transportation duties for the deployment of British troops in the city and orders to fly bombers over the harbour.[48] Around 1,200 air force strikers began a procession in the city alongside the ratings.[47] The procession was joined in by striking servicemen from the Naval Accounts Civilian Staff.[47]

Meanwhile, the Viceroy's Executive Council convened a meeting and came to the decision to stand firm and accept only unconditional surrender, refusing any notions of a parley.[15] Rear Admiral Rattray issued an order to confine all the naval ratings back into their quarters at the barracks by 15:30.[38] General Rob Lockhart, the commanding officer of the Southern Command was given charge of suppressing the mutiny.[16] Royal Marines and the 5th Mahratta Light Infantry were deployed in Bombay to push the agitating ratings out of Bombay and back into their barracks.[49][50]

The strike committee had advised mutineers to refrain from engaging in combat with the army personnel in the city,[14] and the ratings hesitant about engaging in a confrontation with the police and the army retreated to the harbour by afternoon.[32] The troops however proved inadequate in pushing the mutineers back into their barracks.[37] Warning shots from machine guns and rifles were fired near the harbour to prevent the army from advancing further.[32] The naval ratings had taken position at the harbour and were well armed with small arms and ammunitions available at the warships, lockers and munitions depots at the naval establishments. The warships in the harbour were armed with Bofors 40 mm anti–aircraft guns and main batteries with 4–inch guns, that had been altered to the advancing troops and directed their guns towards the land.[37] HMIS Narbada and HMIS Jumna took up positions, pointing their batteries at the oil storage and other military buildings on the Bombay shoreline.[38]

In the evening, Admiral Godfrey reached Bombay after being flown in from the headquarters at New Delhi.[51] The army had formed an encirclement around the harbour and naval districts.[52] The ratings informed The Free Press Journal that the government was attempting to enforce a blockade and cut off food supply to them.[53] During the same time, Godfrey offered to accede to one of the demands, that of improvement in the quality of food which reportedly baffled the mutineers.[53] Parel Mahila Sangh, a communist–affiliated union organised food relief from fishermen and mill workers in Bombay, to be shipped into the harbour.[13]

On 21 February 1946, Admiral John Henry Godfrey released a statement on the All India Radio, threatening the mutineers to surrender immediately or face complete destruction.[54] He had conferred with the First Sea Lord (Chief of Naval Staff), Sir Andrew Cunningham who recommended the swift suppression of the mutiny to prevent it from turning into a greater military conflict.[44] The British flotilla of the Royal Navy, consisting of the cruiser HMS Glasgow, three frigates and five destroyers were called in from Singapore.[55][44] Bombers from the Royal Air Force were flown over the harbour as a show of strength.[54][32]

The Royal Marines were directed to re–take the Castle Barracks,[55] the mutineers entered into fire fights on some of the army positions on land.[50] The mutineers attempted a probe into the city but the army successful repulsed it, preventing them from surging into Bombay.[50] Godfrey sent a message to the British Admiralty requesting urgent assistance and stating that the mutineers possessed capabilities to take the city.[4] Meanwhile, the ratings manning shops at the harbour exchanged rifle fire with advancing British troops of the 5th Mahratta Light Infantry.[15] Salvos from the main guns of the RIN warships were fired at the British troops approaching the barracks.[56]

Around 16:00, the firing from the warships were ceased following instructions from the Strike Committee and the ratings retreated out of the barracks.[4] The marines stormed the barrack facilities in the evening, seized the munitions storage and secured all the entrances and exits of the barracks.[55] With the marines having gained a foothold inside the harbour, the Central Strike Committee was moved from the shore establishment HMIS Talwar to the state of the art warship HMIS Narbada.[14]

In the meantime, Royal Indian Air Force personnel from the Andheri and Colaba camps revolted and joined up with the naval ratings. Sporting white flags spattered with fake blood,[57] around 1,000 airmen occupied the Marine Drive of Bombay.[58] The contingent issued their own set of demands mimicking the Charter of Demands and included a demand for standardisation of pay scales with the Royal Air Force (RAF).[53] The Royal Indian Air Force personnel at the Sion area began a strike in support of the mutineers.[46]

Civil unrest in Bombay

On 22 February 1946, British reinforcements in the form of battalions from the Essex Regiment, the Queen's Regiment and the Border Regiment, along with 146th Regiment of the Royal Armoured Corps arrived at Bombay from Poona, Bombay Province. This was followed in quick succession with the arrival of an anti–tank battery from the Field Regiment of the Royal Artillery stationed in Jubbulpore.[55] Curfew was imposed in the city. Fearing a wider, communist–inspired rebellion in the country, the government decided to crack down on the agitators.[54] Over the course of the unrest, up to 236 people were killed and thousands were injured, though these figures include communal violence sparked by the mutiny.[44] On 23 February 1946, the Naval Central Strike Committee requested all the warships to fly black flags of surrender.[59]

HMIS Hindustan and Karachi

The news of the mutiny at HMIS Talwar reached Karachi on 19 February 1946.[35][32] In the afternoon, the naval ratings from the shore establishments HMIS Bahadur, HMIS Himalaya and HMIS Monze called a meeting of ratings at the beach of Manora Island through the Saliors' Association in Karachi. The general body came to a unanimous decision to launch an agitation on 21 February with a procession beginning at the Keamari jetty on the mainland and eventually moving through the city in opposition to British rule and endorsing unity between the Indian National Congress and the All–India Muslim League.[60]

However, on 20 February 1946, before the planned procession could occur, a dozen naval ratings on the old sloop HMIS Hindustan disembarked from the ship and refused to return unless certain officers were transferred, in protest against discrimination faced by them.[61] Over the course of the day, the group began to swell as naval ratings from HMIS Himalaya followed by ratings from other establishments joined them. The group moved into the Keamari locality with slogans such as "Inquilab Zindabad" (transl. Long live the revolution), "Hindustan Azad" (transl. Freedom for India), urging commercial establishments to begin a general strike and eventually began a march towards the railway station claiming that they intended to march on Delhi. In the meantime, a second meeting was called which quickly came to the decision to drop the planned agitation and support the activities of the ratings in the city. The ratings working through the association, organised for walls in the naval areas and in the city to be struck with posters and painted with galvanising slogans such as "We shall live as a free nation" and "Tyrants your days are over", among others.[62]

Occupation of Manora Island

In the morning of 21 February 1946, Manora Island was rife with unrest.[62] The warship HMIS Hindustan docked at the Karachi Harbour had been seized by the naval ratings at midnight, the officers subdued,[55][48] and the warship moored at the Manora Island.[63] Within hours of the mutiny at HMIS Hindustan, the trainings establishment HMIS Bahadur, the radar school HMIS Chamak and the gunnery school HMIS Himalaya were seized by around 1,500 naval ratings,[64] all located on the island.[63] The British officers at HMIS Bahadur shot and killed one of the ratings during the process, whose blood soaked shirt became the flag for the mutineers.[65] The other military vessel in the harbour, HMIS Travancore was also seized by the ratings.[48]

The mutiny at the naval establishments at Manora were joined by local residents.[65] By morning, the mutineers were crossing over to Keamari on civilian and military motor launches from the jetty of HMIIS Himalaya. Some of the ratings were caught on their way by British manned patrol boats that fired at them and retreated when HMIS Hindustan began shelling in their direction with up its twelve–pounder guns. Two ratings on the launches died and several were wounded in the minor confrontation.[62]

In the meantime, troops from the 44th Indian Airborne Division, the Black Watch and a battery of the Royal Regiment of Artillery were deployed in Karachi for assistance.[55][63] According to unconfirmed reports, many of the Indian regiments refused to fire at the mutineers.[65][66] The army predominantly relied on British troops for the duration of the mutiny and the civil unrest in the city that followed afterwards.[66]

The authorities were in close contact with their counterparts in Bombay and intended to prevent a similar collaboration between mutineers and civilians that had reportedly led to a critical situation in Bombay.[67] Cordons were placed at the bridges connecting Keamari with the rest of the city by the police, along with British troops armed with Thompson submachine guns.[67][64] The cordons prevented the mutineers from entering the city and hundreds of ratings were pinned down at the Keamari area throughout the day. Local workers at the dockyards joined up with the ratings and held demonstrations with slogans calling for revolution.[67]

In the evening, the mutineers at Keamari fixed rendezvous points with the workers and boatmen, and returned to the island. The mutineers held a number of meetings at night on the island to deliberate upon a plan of action for the following day. Around 11:00 pm, HMIS Chamak, the radar school received information from HMIS Himalaya, the gunnery school and jetty on the island that HMIS Hindustan had received an ultimatum from the authorities to surrender by 10:00 am. HMIS Hindustan was the sole warship in the area and commanded the passage into the Karachi Harbour.[67] In the morning of 22 February 1946, Commodore Curtis, the British commanding officer at the harbour held parley at 8:30 am, coming on board the ship in an effort to persuade the ratings to surrender, and providing "safe conduct" to those who would do so by 9:00 am.[68] The ultimatum's time delineation had been adjusted with the low tide which put the warship off the shore at a strategically disadvantageous position with respect to troops on land.[67]

The parley drew no response and the ultimatum was ignored, the ratings were observed to be in preparations for manning the ship's armaments.[69] Altered by this development, the British troops advanced through Keamari and attempted to board HMIS Hindustan,[4] beginning with sniper fire from a distance directed at those on the deck of the ship. The mutineers returned fire with the Oerlikon 20 mm cannons on the ship,[69] heavy machine guns on board the ship were also utilised.[4] Two four–inch main guns on board the ship were primed although their field of vision of impaired due to low tide. In a retaliatory measure, the artillery battery fired at the ship with mortars and field guns,[69] including the 75 millimeter howitzers.[4] The warship refrained from retaliating with its full armament to avoid hitting sympathetic civilian targets in the city in light of its impaired vision.[70] One of the main gun turrets exploded due to the shelling resulting in a fire aboard the ship, while it was attempting to leave the harbour. On this turn of events at 10:55, the mutineers at HMIS Hindustan surrendered and the battle had ended.[69]

In the morning, the government issued a public warning, stating that lethal force would be used against anyone approaching within a mile of HMIS Hindustan. This delayed the crossing of mutineers from Manora to Keamari as it significantly reduced the number of boatmen willing to assist them. The confrontation with HMIS Hindustan had ended by the time some of the ratings made it across were met with British troops that had advanced into and occupied Keamari.[71] In the meantime, British paratroopers captured the shore establishments on the island.[72] The Black Watch was also directed to re–take Manora Island,[63] who according to an Intelligence Bureau report to the Home Department had captured the gunnery school at 9:50 am. The report further stated that the casualties at the time were 7 RIN ratings and 15 paratroopers wounded on the island.[73] The remaining ratings were trapped at the jetty on Manora, unable to cross over to Keamari and faced with the Black Watch behind them.[71] In the end, 8–14 were killed, 33 wounded including British troops and 200 mutineers arrested.[71][4]

Civil unrest in Karachi

Movement and communication between Keamari and Karachi were cut off with the placement of a military and police cordon from 21 February onward.[74] Civilian dhows at Keamari were confiscated by British authorities and brought into the city,[75] and the military deployment searched vehicles that had entered the city from Keamari to prevent mutineers from infiltrating Karachi.[76] Much of the population was concentrated near the ports and Keamari in particular was densely populated with a heavy working–class concentration,[77] as a result civilian life was severely disrupted with the military deployment and the placement of cordons.[75] Exaggerated narrations of events spread through the city, and the civilian population, which was already sympathetic to the mutineers, were galvanized along with growing apprehensions for the military presence.[76] The narrations included rumours and were primarily spread by the expropriated boatmen and fishermen who were able to maintain some lines of communication with those in Keamari.[75]

On 22 February 1946, flashes of firing and sounds of gunfire from the confrontation could be seen and heard in Karachi.[75] The port area was swarmed with military vehicles where some of them were vandalised by civilians.[75] Indian military police were heckled and jeered at by crowds while British troops, military trucks and dispatches were attacked with stones on several routes.[75] The mutineers surrendered but civil unrest had begun to sweep through the city.[78] The protests which began spontaneously in the preceding days, became more organised with the involvement of students and local leaders.[75] In the evening, the Communist Party of India held a public meeting at the Karachi Idgah park, which witnessed a gathering of around 1,000 people and was presided over by Sobho Gianchandani.[79] According to the authorities, "dangerous and provocative anti–British speeches" were made at this assembly; an expression prominent in the meeting was that the mutineers had shown them how the arms provided to them could really be utilised while civilians were helpless because of the lack of weapons or contact with the mutineers. The meeting concluded with the decision to call for a city–wide hartal (transl. general strike) on the following day.[80]

On 23 February 1946, Karachi observed a complete shutdown with warehouses and stores closed,[78] tramway workers on strike,[81] and students from college and schools demonstrating on the streets.[78] The authorities, in an attempt to prevent civil unrest which was witnessed in Bombay a day earlier, arrested three prominent communist leaders in the city and the district magistrate imposed a section 144 order in the Karachi district which prohibited gatherings of more than three people.[82] The police force was however ineffective in enforcing the order due to low morale in the force, abstentions and instances of collusion between police personnel and civilian agitators. Over the course of the day, the streets filled as more and more people joined mass demonstrations and gatherings.[78]

Numerous mass gatherings, meetings and demonstrations were held while the Communist Party of India led a procession of 30,000 people through the city.[78] The subdued naval ratings on Manora Island also carriedout a hunger strike while in custody. Many of the striking ratings, some of whom were identified as their leaders, were arrested by the authorities and sent to the military prison camp at Malir in the Thar Desert.[71] At noon, a crowd of thousands had formed at Idgah park which was joined by the Communist Party–led procession.[78] The police force was eventually deployed at the park who were repulsed after several attempts to disperse the crowd. Idgah had become a centre of resistance for the protesters, where later in the day, some of the communist leaders called for the protesters to disperse but were unable to contain the majority of the crowd who were galvanised by the previous day's radical messages and attacked the nearby police personnel.[83]

The government called for the armed forces to be deployed in the city and the crowd at the park, faced with the arrival of the troops, scattered into smaller groups. The troops occupied the park in the afternoon, but the smaller groups, inflamed by their deployment, targeted government establishments such as post offices, police stations and the sole European–owned Grindlays Bank in the city.[84] Government buildings were vandalised by smaller groups throughout the city and a sub–post office burned to the ground. One group attempted to capture the municipal building but were prevented by the police who arrested 11 youths, including a Communist Party leader. The crowds targeted Anglo–Indians, Europeans and occasionally Indian government servants, who were stripped of their hats and ties, which were then burnt on the ground. This was followed by police moving through the streets and on several occasions resorting to opening fire to disperse the crowds. The crowds, which were primarily composed of students and working–class people, dispersed at night as they returned to their homes.[81]

On 24 February 1946, the military forces in the city successfully enforced a curfew. The unrest subsided over the following days and the military presence was removed by the end of 26 February. Estimates of casualties from the shootings come only from official figures: 4–8 killed, 33 injured from police firings in self–defense and 53 policemen injured.[81]

Other revolts and incidents

On 20 February 1946, it was reported that with the aid of radio and telegraph messages from the Signals School and Central Communications Office in Bombay, the mutiny had spread to all RIN sub stations in India, located at Madras, Cochin, Vizagapatam, Jamnagar, Calcutta and Delhi.[85] The Bombay telegraphs also requested assistance from Royal Indian Air Force (RIAF) and Royal Indian Army Service Corps (RIASC).[86] During the mutiny, the supplies provided to the RIASC was pilfered by servicemen and sold off to the mutineers through the black market.[87] HMIS India, the naval headquarters at New Delhi witnessed around 80 signals operators refusing to following commands and barricading themselves inside their station.[64][53]

On 22 February 1946, large–scale agitations by civilians began across several cities other than Bombay and Karachi, such as Madras, Calcutta and New Delhi. Looting was widespread and directed at government institutions, grains stores were looted by the impoverished, as were jewelry shops and banks. Criminal elements known as goondas were also reportedly involved.[21]

Andaman Sea

The minesweeper flotilla of the Royal Indian Navy, with its command warship HMIS Kistna was stationed in the Andaman Sea.[88] The flotilla included six other ships namely, HMIS Hongkong, HMIS Bengal (J243), HMIS Rohilkhand (J180), HMIS Deccan (J129), HMIS Baluchistan (J182) and HMIS Bihar (J247).[89] HMIS Kistna received news of the mutiny in Bombay during the breakfast hour on 20 February 1946. The commanding officer of the flotilla addressed the personnel at 16:00 expressing sympathies with "legitimate aspirations" while emphasizing the importance of maintaining order and discipline. The following day, further broadcasts increased tensions between the officers and the naval ratings, and rumours began to spread among the sailors. Lacking direct communication with the mutineers and access to print news, the ratings were primarily informed about the mutiny by the officers and were unable to understand the situation in Bombay.[88]

On 23 February 1946, all seven ships of the minesweeper flotilla ceased duties and went on strike.[86]

Kathiawar

Godfrey had issued a statement through the All India Radio giving the example of the shore establishment HMIS Valsura at Jamnagar for having the stayed loyal and threatening the destruction of the navy if the mutineers didn't surrender. The broadcast reportedly agitated the ratings.[90]

In Morvi State, a transport vessel named SS Kathiawar had set out for sea on 21 February 1946. The ship was seized by the 120 ratings on board after receiving a radio transmission for assistance from the warship HMIS Hindustan in Karachi. The ship was subsequently diverted towards Karachi but HMIS Hindustan surrendered before they could reach their designation which prompted them to redirect towards Bombay. The mutiny had however ended by the time it reached the city.[90]

Madras

On 19 February 1946, around 150 naval ratings mutinied at the shore establishment and naval base HMIS Adyar in Madras, Madras Presidency. The mutineers paraded through the streets of the city shouting slogans and attacked the British officers who attempted to impede them in their activities.[43]

1,600 personnel with the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers at Avadi publicised their decision to refuse orders and initiate a general strike.[55]

On 25 February 1946, the city of Madras observed complete shut down as a result of a general strike.[90]

Punjab

On 22 February 1946, the stations of the RIAF in Punjab witnessed a mass general strike. Several demonstrations in the bazaars (transl. marketplaces) were held across the province by the personnel from the force warning the government against shooting at Indians and demanding the release of the Indian National Army soldiers.[45]

Calcutta

On 22 February 1946, the naval ratings of the frigate HMIS Hooghly (K330) began refusing orders in protest against the violent suppression of the mutiny in Bombay and Karachi. The Communist Party of India called a general strike in the city and around 100,000 workers participated in mass demonstrations and agitations over the following days.[90]

On 25 February 1946, a detachment of troops surrounded the frigate located at the Kolkata Harbour and arrested the disobedient ratings, who were imprisoned. The general strike in the city came to an end on the following day.[90]

Vizagapatnam

On 22 February 1946, the British troops arrested 306 mutineers without use of force.[55]

Lack of support

The mutineers in the armed forces received no support from national political leaders and were themselves largely leaderless.

Mahatma Gandhi condemned the revolt. His statement on 3 March 1946 criticized the strikers for revolting without the call of a "prepared revolutionary party" and without the "guidance and intervention" of "political leaders of their choice". He added: "If they mutinied for the freedom of India they were doubly wrong. They could not do so without a call from a prepared revolutionary party."[91] He further criticized the local Indian National Congress leader Aruna Asaf Ali, who was one of the few prominent political leaders of the time to offer support for the mutineers, stating that she would rather unite Hindus and Muslims on the barricades than on the constitutional front. Gandhi's criticism also belies the submissions to the looming reality of Partition of India, having stated "If the union at the barricade is honest then there must be union also at the constitutional front."

The Muslim League made similar criticisms of the mutiny, arguing that unrest amongst the sailors was not best expressed on the streets, however serious their grievances might be. Legitimacy could only, probably, be conferred by a recognised political leadership as the head of any kind of movement. Spontaneous and unregulated upsurges, as the RIN strikers were viewed, could only disrupt and, at worst, destroy consensus at the political level. This may be Gandhi's (and the Congress's) conclusions from the Quit India Movement in 1942 when central control quickly dissolved under the impact of suppression by the colonial authorities, and localised actions, including widespread acts of sabotage, continued well into 1943. It may have been the conclusion that the rapid emergence of militant mass demonstrations in support of the sailors would erode central political authority if and when transfer of power occurred. The Muslim League had observed passive support for the "Quit India" campaign among its supporters and, devoid of communal clashes despite the fact that it was opposed by the then collaborationist Muslim League. It is possible that the League also realised the likelihood of a destabilised authority as and when power was transferred. This certainly is reflected on the opinion of the sailors who participated in the strike. It has been concluded by later historians that the discomfiture of the mainstream political parties was because the public outpourings indicated their weakening hold over the masses at a time when they could show no success in reaching agreement with the British Indian government.

The Communist Party of India, the third largest political force at the time, extended full support to the naval ratings and mobilised the workers in their support, hoping to end British rule through revolution rather than negotiation. The two principal parties of British India, the Congress and the Muslim League, refused to support the ratings. The class content of the mass uprising frightened them and they urged the ratings to surrender. Patel and Jinnah, two representative faces of the communal divide, were united on this issue and Gandhi also condemned the 'Mutineers'. The Communist Party gave a call for a general strike on 22 February. There was an unprecedented response and over a lakh students and workers came out on the streets of Calcutta, Karachi and Madras. The workers and students carrying red flags paraded the streets with the slogans "Accept the demands of the ratings" and "End British and Police zoolum". Upon surrender, the ratings faced court–martial, imprisonment and victimisation. Even after 1947, the governments of Independent India and Pakistan refused to reinstate them or offer compensation. The only prominent leader from Congress who supported them was Aruna Asaf Ali. Disappointed with the progress of the Congress Party on many issues, Aruna Asaf Ali joined the Communist Party of India (CPI) in the early 1950s.

It has been speculated that the actions of the Communist Party to support the mutineers was partly born out of its nationalist power struggle with the Indian National Congress. M. R. Jayakar, who was a Judge in the Federal Court of India (which later became the Supreme Court of India), wrote in a personal letter

There is a secret rivalry between the Communists and Congressmen, each trying to put the other in the wrong. In yesterday’s speech Vallabhbhai almost said, without using so many words, that the trouble was due to the Communists trying to rival the Congress in the manner of leadership.

The only major political segments that still mentions the revolt are the Communist Party of India and the Communist Party of India (Marxist). The literature of the Communist Party portrays the RIN Revolt as a spontaneous nationalist uprising that had the potential to prevent the partition of India, and one that was essentially betrayed by the leaders of the nationalist movement.

More recently, the RIN Revolt has been renamed the Naval Uprising and the mutineers honoured for the part they played in India's independence. In addition to the statue which stands in Mumbai opposite the sprawling Taj Wellingdon Mews, two prominent mutineers, Madan Singh and B.C. Dutt, have each had ships named after them by the Indian Navy.

Aftermath

Between 25 and 26 February 1946, the rest of the mutineers surrendered with a guarantee from the Indian National Congress and the All–India Muslim League that none of them would be persecuted.[4] Contingents of the naval ratings were arrested and imprisoned in camps with distressing conditions over the following months, despite resistance from national leaders,[5] and the condition of surrender which shielded them from persecution.[4]

Precautionary measures were taken against possibility of a second rebellious outbreak. Firing mechanisms were removed from the warships, small arms kept under lock by British officers and army troops were deployed as guards on board warships and at the shore establishments. British admirals, despite the mutiny, were unwilling to cede control and retained assumptions of the navy acting as an instrument of British interests in the Indian Ocean.[11]

In British circles, confidence in the loyalty and reliability of the Royal Indian Navy was shattered.[11] The mutiny marred the reputation of John Henry Godfrey.[63] He became known for professional neglect and was blamed for losing control of the navy during the mutiny.[12] Godfrey took responsibility for his inability to prevent and contain the rebellion, which had jeopordised British security in the Indian Ocean.[92] Although he was not held responsible in any official naval proceedings and continued to serve the British Admiralty, he was informally rebuked through means such as being overlooked in award of honors.[12]

Precautions

On 23 March 1946, Vice Admiral Geoffrey Audley Miles replaced Godfrey as Flag Officer Commanding Royal Indian Navy. Between June 1941 to March 1943, Miles had served as the head of the British naval mission in Moscow and was responsible for coordinating British naval operations with the Soviet Navy. He was appointed as the commanding officer of the British naval forces in Western Mediterranean from March 1943 till the end of the war, and was the British representative at the Tripartite Naval Commission. The diplomatic experience of Miles hence led to a perceptions of him being best suited to deal with the aftermath of the mutiny by the British government and expectations on him remained high.[12]

The change in leadership did not bring about change in attitudes in the British naval leadership and Miles embraced the vision for the near and long term of the navy that had been pervaded by Godfrey. He continued to employ British naval officers and no changes were made in the hierarchy of command. Miles personally visited all the shore establishments, paid off the lease on the smaller warships and sent the larger warships for exercises at sea on a continual basis. The schedule was made more hectic to keep the naval ratings distracted and minimize routine contact with the civilian population. The warships remained disarmed and the small arms out of access during the exercises. No further unrest occurred in the navy and Miles was considered to have been at least partially successful in restoring confidence in the reliability in the Royal Indian Navy.[12]

Following independence, the navy was divided in two, but British officers remained in positions of authority within the two navies; the Royal Indian Navy (later renamed to Indian Navy) and the Royal Pakistan Navy (later renamed to Pakistan Navy). Vice Admiral William Edward Parry became the commanding officer of the Indian Navy. None of the discharged sailors were pardoned or reinstated in either navy.[93]

Many sailors on HMIS Talwar were reported to have communist leanings and on a search of 38 sailors who were arrested on HMIS New Delhi, 15 were found to be subscribers to CPI literature. The British later came to know that the revolt, though not initiated by the Communist Party of India, was inspired by its literature.

Investigations

Numerous boards of inquiry were set up at the shore establishments and naval bases across India by the naval authorities as factfinding bodies to investigate the causes and circumstances of the mutiny. The bodies consisted of British armed forces officers and primarily took witness testimonies of RIN officers with a small cross–section of other ranks. The cause of the mutiny was determined to have its basis in administrative deficiencies such as inadequate information, failure of regular inspections, lack of experienced petty officers, chiefs and officers.

On 8 March 1946, Commander–in–Chief Sir Claude Auchinleck recommended a commission of inquiry determine the causes and origin of the mutiny.[94] The commission of inquiry's members were:

- The Hon'ble Sir Saiyid Fazl Ali, Chief Justice of Patna High Court (Chairman)

- Mr. Justice K. S. Krishnaswami Iyengar, Chief Justice, Cochin State

- Mr. Justice Mahajan, Judge, Lahore High Court

- Vice-Admiral W. R. Patterson, CB, CVO, Flag Officer Commanding, Cruiser Squadron in the East Indies Fleet

- Major-General T. W. Rees, CB, CIE, DSO, MC, Indian Army, Commanding the 4th Indian Division

The commission became highly politicised. It was criticised for being over–legalistic, selective in its conduct and antagonistic towards the military institution.[10] Its report was publicly released in January 1947.[95] British naval officers remained skeptical of its findings.[96]

Impact

Indian historians have looked at the mutiny as a protest against racial discrimination and supply of bad food by the British officials.[97] British scholars note that there was no comparable unrest in the Army, and have concluded that internal conditions in the Navy were central to the mutiny. There was poor leadership and a failure to instill any belief in the legitimacy of their service. Furthermore, there was tension between officers (mostly British), petty officers (largely Punjabi Muslims), and junior ratings (mostly Hindu), as well as anger at the very slow rate of release from wartime service.

The grievances focused on the slow pace of demobilisation. British units were near mutiny and it was feared that Indian units might follow suit. The weekly intelligence summary issued on 25 March 1946 admitted that the Indian Army, Navy and Air Force units were no longer trustworthy, and, for the Army, "only day to day estimates of steadiness could be made". The situation has thus been deemed the "Point of No Return."[98]

The British authorities in 1948 branded the 1946 Indian Naval Mutiny as a "larger communist conspiracy raging from the Middle East to the Far East against the British crown".

However, probably just as important remains the question as to what the implications would have been for India's internal politics had the revolt continued. The Indian nationalist leaders, most notably Gandhi and the Congress leadership, had apparently been concerned that the revolt would compromise the strategy of a negotiated and constitutional settlement, but they sought to negotiate with the British and not within the two prominent symbols of respective nationalism—–the Congress and the Muslim League.

In 1967 during a seminar discussion marking the 20th anniversary of Independence; it was revealed by the British High Commissioner of the time John Freeman, that the mutiny of 1946 had raised the fear of another large–scale mutiny along the lines of the Indian Rebellion of 1857, from the 2.5 million Indian soldiers who had participated in the Second World War.[99]

Legacy

The rising was championed by Marxist cultural activists from Bengal. Salil Chaudhury wrote a revolutionary song in 1946 on behalf of the Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA). Later, Hemanga Biswas, another veteran of the IPTA, penned a commemorative tribute. A Bengali play based on the incident, Kallol (Sound of the Wave), by radical playwright Utpal Dutt, became an important anti–establishment statement, when it was first performed in 1965 in Calcutta. It drew large crowds to the Minerva Theatre where it was being performed; soon it was banned by the Congress government of West Bengal and its writer imprisoned for several months.

The revolt is part of the background to John Masters' Bhowani Junction whose plot is set at this time. Several Indian and British characters in the book discuss and debate the revolt and its implications.

The 2014 Malayalam movie Iyobinte Pusthakam directed by Amal Neerad features the protagonist Aloshy (Fahadh Faasil) as a Royal Indian Navy mutineer returning home along with fellow mutineer and National Award–winning stage and film actor P. J. Antony (played by director Aashiq Abu)

See also

Naval mutinies:

Notes and references

- ^ Bell, C.M.; Elleman, B.A. (2003). Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective. Cass series. Frank Cass. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-7146-5460-7.

- ^ Mohanan 2019, p. 208.

- ^ Narasiah, K. R. A. (7 May 2022). "1946 Last War of Independence Royal Indian Navy Mutiny review: The 1946 naval uprising". The Hindu.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Spector 1981, p. 274.

- ^ a b Vitali 2018, p. 3-4.

- ^ a b c d Madsen 2003, p. 175.

- ^ Madsen 2003, pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b c Jena 1996, p. 488.

- ^ a b Jena 1996, p. 489.

- ^ a b c d e f Madsen 2003, p. 177.

- ^ a b c d Madsen 2003, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e Madsen 2003, p. 182.

- ^ a b Vitali 2018, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Meyer 2017, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Spector 1981, p. 273.

- ^ a b c d e Marston 2014, p. 143.

- ^ a b Jena 1996, p. 490.

- ^ a b Meyer 2017, p. 10.

- ^ a b Vitali 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Spence 2015, p. 489.

- ^ a b Spence 2015, p. 493.

- ^ a b Meyer 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Gourgey 1996, p. 5.

- ^ Meyer 2017, p. 7-8.

- ^ Meyer 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Meyer 2017, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c Davies 2019, p. 5.

- ^ a b Meyer 2017, p. 9.

- ^ Madsen 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Spence 2015, p. 491.

- ^ a b c Spence 2015, p. 492.

- ^ a b c d e f Jena 1996, p. 485.

- ^ Madsen 2003, pp. 178–179.

- ^ a b Meyer 2017, p. 20.

- ^ a b Davies 2014, p. 387.

- ^ a b c d e f g Spector 1981, p. 271.

- ^ a b c d Madsen 2003, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 1993, p. 193.

- ^ a b c Singh 1986, p. 90.

- ^ Singh 1986, p. 92.

- ^ Spence 2015, pp. 497–498.

- ^ Singh 1986, pp. 90–91.

- ^ a b c Spector 1981, p. 272.

- ^ a b c d e f Madsen 2003, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Javed 2010, p. 6.

- ^ a b Jena 1996, p. 486.

- ^ a b c d Javed 2010, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Javed 2010, p. 3.

- ^ Marston 2014, pp. 143–144.

- ^ a b c Marston 2014, p. 144.

- ^ Richardson 1993, p. 197.

- ^ Meyer 2017, pp. 11–12.

- ^ a b c d Meyer 2017, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Davies 2019, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Richardson 1993, p. 198.

- ^ Madsen 2003, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Dayal 1995, p. 228.

- ^ Bose 1988, p. 166.

- ^ Vitali 2018, p. 3.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 2.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 2-3.

- ^ a b c Deshpande 1989, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e West 2010, p. 125.

- ^ a b c Gourgey 1996, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Javed 2010, p. 4.

- ^ a b Deshpande 1989, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e Deshpande 1989, p. 4.

- ^ Richardson 1993, p. 198-199.

- ^ a b c d Richardson 1993, p. 199.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 4-5.

- ^ a b c d Deshpande 1989, p. 5.

- ^ Javed 2010, p. 4-5.

- ^ Sarkar & Bhattacharya 2007, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 9-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g Deshpande 1989, p. 10.

- ^ a b Deshpande 1989, p. 9.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 7-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Deshpande 1989, p. 12.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 10-11.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Deshpande 1989, p. 14.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 11-12.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 12-13.

- ^ Deshpande 1989, p. 13-14.

- ^ Richardson 1993, p. 193-194.

- ^ a b Richardson 1993, p. 194.

- ^ Spence 2015, p. 494.

- ^ a b Spence 2015, p. 496.

- ^ Singh 1986, p. 91-92.

- ^ a b c d e Javed 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Gourgey 1996, p. 57.

- ^ West 2010, p. 126.

- ^ Meyer 2017, p. 16.

- ^ Singh 1986, p. 79.

- ^ Madsen 2003, p. 187.

- ^ Madsen 2003, p. 177-178.

- ^ Pandey, B.N. (1976). Nehru (in German). Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-349-00792-9. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Kapoor, Pramod (2022). 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny: Last War of Independence (in German). Roli Books. p. 253. ISBN 978-939-2-13028-1. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Aiyar, Swaminathan S. Anklesaria. "Swaminathan S Anklesaria Aiyar: Freedom, won by himsa or ahimsa?". The Economic Times. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

General references

- Bhagwatkar, V. M. (1976). "The R. I. N. Mutiny of Bombay—February, 1946". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 37: 387. JSTOR 44138995.

- Bose, Biswanath (1988). Rin Mutiny, 1946: Reference and Guide for All. Northern Book Centre. ISBN 978-81-85119-30-4.

- Chandra, Bipan; Mukherjee, Mridula; Mukherjee, Aditya; Panikkar, K. N.; Mahajan, Sucheta (2000). India's struggle for independence, 1857-1947. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-81-8475-183-3.

- Davies, Andrew (October 2019). "Transnational connections and anti-colonial radicalism in the Royal Indian Navy mutiny, 1946". Global Networks. 19 (4): 521–538. doi:10.1111/glob.12256. S2CID 199807923.

- Davies, Andrew D. (3 July 2014). "Learning 'Large Ideas' Overseas: Discipline, (im)mobility and Political Lives in the Royal Indian Navy Mutiny". Mobilities. 9 (3): 384–400. doi:10.1080/17450101.2014.946769. S2CID 144917512.

- Davies, Andrew (August 2013). "Identity and the assemblages of protest: The spatial politics of the Royal Indian Navy Mutiny, 1946". Geoforum. 48: 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.03.013.

- Dayal, Ravi (1995). We Fought Together for Freedom: Chapters from the Indian National Movement. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563286-6.

- Deshpande, Anirudh (March 1989). "Sailors and the crowd: popular protest in Karachi, 1946". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 26 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1177/001946468902600101. S2CID 144466285.

- Gourgey, Percy S. (1996). The Indian Naval Revolt of 1946. Chennai: Orient Longman. ISBN 9788125011361.

- Javed, Ajeet (2010). "The United Struggle of 1946". Pakistan Perspectives. 15 (1). Karachi: 146–154. ProQuest 919609575.

- Jeffrey, Robin (April 1981). "India's Working Class Revolt: Punnapra-Vayalar and the Communist 'Conspiracy' of 1946". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 18 (2): 97–122. doi:10.1177/001946468101800201. S2CID 143883855.

- Jena, Teertha Prakash (1996). "Challenge in Royal Indian Navy (1946) - a Revaluation of Its Causes". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 57: 485–491. JSTOR 44133352.

- Louis, Roger (2006). The Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonisation. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84511-347-6.

- Madsen, Chris (2003). "The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny, 1946". In Bell, Christopher; Elleman, Bruce (eds.). Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective. Routledge. pp. 175–192. ISBN 978-1-135-75553-9.

- Marston, Daniel (2014). "Question of loyalty? The Indian National Army and the Royal Indian Navy mutiny". The Indian Army and the End of the Raj. Cambridge University Press. pp. 116–150. ISBN 978-0-521-89975-8.

- Meyer, John M. (2 January 2017). "The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946: Nationalist Competition and Civil-Military Relations in Postwar India". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 45 (1): 46–69. doi:10.1080/03086534.2016.1262645. S2CID 159800201.

- Mohanan, Kalesh (2019). The Royal Indian Navy: Trajectories, Transformations and the Transfer of Power. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-70957-5.

- Pati, Biswamoy (2009). "From the Parlour to the Streets: A Short Note on Aruna Asaf Ali". Economic and Political Weekly. 44 (28): 24–27. JSTOR 40279255.

- Richardson, William (January 1993). "The Mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy at Bombay in February 1946". The Mariner's Mirror. 79 (2): 192–201. doi:10.1080/00253359.1993.10656448.

- Sarkar, Sumit; Bhattacharya, Sabyasachi (2007). Towards Freedom: Documents on the Movement for Independence in India, 1946. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-569245-7.

- Singh, Satyindra (1986). Under Two Ensigns: The Indian Navy, 1945-1950. Oxford & IBH Publishing Company. ISBN 978-81-204-0094-8.

- Spector, Ronald (January 1981). "The Royal Indian Navy Strike of 1946: A Study of Cohesion and Disintegration in Colonial Armed Forces". Armed Forces & Society. 7 (2): 271–284. doi:10.1177/0095327X8100700208. S2CID 144234125.

- Spence, Daniel Owen (27 May 2015). "Beyond Talwar : A Cultural Reappraisal of the 1946 Royal Indian Navy Mutiny". The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 43 (3): 489–508. doi:10.1080/03086534.2015.1026126. S2CID 159558723.

- Talbot, Ian (December 2013). "Safety First: The Security of Britons in India, 1946—1947". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. 23: 203–221. doi:10.1017/S0080440113000091. JSTOR 23726108. S2CID 143417672.

- Vitali, Valentina (2 October 2018). "Meanings of Failed Action: A Reassessment of the 1946 Royal Indian Navy Uprising" (PDF). South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies. 41 (4): 763–788. doi:10.1080/00856401.2018.1523106. S2CID 149478354.

- West, Nigel (2010). Historical Dictionary of Naval Intelligence. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-7377-3.