The Chinese in America

First edition cover | |

| Author | Iris Chang |

|---|---|

| Audio read by | Nancy Wu |

| Language | English |

| Subject | History of Chinese Americans |

| Genre | |

| Publisher | Viking Penguin |

Publication date | April 2003 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 448 pages |

| ISBN | 978-0-670-03123-8 |

| OCLC | 779670934 |

| 973.04951 | |

| LC Class | E184.C5 C444 2003 |

The Chinese in America: A Narrative History is a non-fiction book about the history of Chinese Americans by Iris Chang. The epic and narrative history book was published in 2003 by Viking Penguin. It is Chang's third book after the 1996 Thread of the Silkworm and the 1997 The Rape of Nanking. Chang was inspired to write the book after relocating to the San Francisco Bay Area, where she had conversations with key figures in the Chinese-American community. She spent four years researching and writing the book, having conducted interviews and reviewed diaries, memoirs, oral histories, national archives, and doctoral theses.

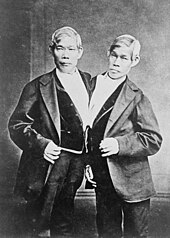

The book provides an overview of Chinese immigrants to the United States and their descendants. It covers several waves of migration: the first was triggered by the California gold rush and the first transcontinental railroad in the 1850s, the second after the Chinese Communist Party took power in 1949, and the third after China's opening up after the late 1970s. The book describes the discrimination that the Chinese experienced including the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the holding of arrivals at Angel Island Immigration Station, and the Wen Ho Lee case. It covers how Chinese Americans engaged in activism against the oppression such as the 1867 Chinese Labor Strike, suing plantation owners who breached agreements, and protesting against the United States' shipping scrap metal to Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War. She weaves people's stories into the overarching historical narrative including vignettes about the "Siamese twins" Chang and Eng Bunker, the news anchor Connie Chung, the architect Maya Lin, the horticulturalist Lue Gim Gong, the Air Force officer Ted Lieu, the author Amy Tan, the actress Anna May Wong, and the entrepreneur Jerry Yang.

Alongside some negative reviews, the book received mostly positive reviews. Reviewers praised the book for being engaging, well-written, and comprehensive. They liked its numerous anecdotes about Chinese Americans. Some commentators criticized the book for being biased and unbalanced in repeatedly bemoaning how poorly Chinese Americans have been treated. They faulted the book for lacking depth in certain areas and for lacking a clearer narrative. An audiobook version was released in 2005.

Biographical background and publication

Iris Shun-Ru Chang was born in Princeton, New Jersey, in 1968 to Shau-Jin and Ying-Ying Chang, two Taiwanese scholars who had received doctorates from Harvard University. When Chang was born, the couple were Princeton University postdoctoral researchers. Mandarin Chinese was Chang's first language, and she learned English in preschool. After skipping a grade, 17-year-old Chang began her studies at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. She initially planned to major in computer science and mathematics. In her third year, she changed her major to journalism. As a student, she reported for The Daily Illini, the Chicago Tribune, and The New York Times and interned at Newsweek. She graduated in 1989 and relocated to Chicago where she reported first for the Associated Press and subsequently for the Chicago Tribune.[1]

Chang resigned from her position at the Chicago Tribune in 1990 to enroll in Johns Hopkins University's science writing master's curriculum. She was 23 years old and several months into the Johns Hopkins courses when the publisher Basic Books gave her a book deal, making her its youngest author. The book was about the scientist Qian Xuesen, who, in the midst of the McCarthy era, was deported back to China, where he established its missile initiative. Chang finished her Johns Hopkins studies in 1991 and published the Qiang book, Thread of the Silkworm, in 1995. Despite receiving favorable reviews, the book was not commercially successful.[1]

Chang was inspired to write her next book, The Rape of Nanking, after attending a Cupertino, California, conference in 1994. The conference was about Japanese war crimes, particularly the 1937 Nanjing Massacre when Japan stormed China during the Second Sino-Japanese War. After seeing horrendous images at the conference, she decided to write about the massacre. Chang spent over two years on investigating and writing the book. She was in Nanjing for a month in 1995 to talk to the victims; she separately talked to the Japanese soldiers who perpetrated the massacre. Researching the war crimes deeply impacted her, causing her to have nightmares and routinely cry. Published in 1997, the book received positive reviews and spent 10 weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list. The book catapulted her into the spotlight; she appeared on television shows and President Bill Clinton asked her to be a guest at Renaissance Weekend.[1]

Following her relocation to the San Francisco Bay Area, Chang became drawn to the history of Chinese Americans in the middle of the 1990s through conversations with key figures in the Chinese-American community.[2] She began working on The Chinese in America in 1999 and completed it in four years.[1] Having been emotionally drained from writing The Rape of Nanking, she said working on The Chinese in America was "like a vacation" that allowed her "to recover from the wounds of writing Nanking".[3] Chang was motivated to write the book owing to the American media's propagation of "offensive stereotypes" about Chinese Americans. Chang described how the Chinese were depicted in animations as having pigtails, slanted eyes, and buck teeth. In movies, Chinese men and women were depicted as secret agents and sex workers, respectively. The Chinese were shown in textbook drawings as using "long, claw-like fingernails to consume snails".[4]

While writing The Chinese in America, Chang consulted diaries, memoirs, oral histories, national archives, and community newspapers.[2][5][6] She conducted numerous interviews and incorporated the story of her family.[2] Chang relied on newly written doctoral theses, a significant number of which were from students who had been born in China.[7] On multiple computers in her house, she catalogued her research in around 4,000 database items.[8] She described the writing process as not challenging but that determining what to include and what to omit was the challenging part.[8][6]

Viking Penguin published The Chinese in America in April 2003.[9][10] Like her two previous books, The Chinese in America discusses efforts by the Chinese people to secure their human rights.[11] Unlike her two previous books which concentrated on particular people and events, The Chinese in America presents a unified storyline of a comprehensive historical period.[12] To promote the work, over the course of 31 days Chang visited 20 cities for her book tour.[13] While visiting Louisville, Kentucky, during a tour for the book, she had a mental health emergency and needed to be admitted to the hospital.[14] According to her literary agent Susan Rabiner, Chang at the time of her death from suicide in 2004 was writing a The Chinese in America book for children.[1]

Style

The Chinese in America is an epic and narrative history.[15][16][17] The book interweaves individual narratives into the overarching historical patterns.[1][10][18] Sian Wu of International Examiner said Chang provides "a diverse, varying portrait" of Chinese people in the United States. Chang profiles both men and women, and the narratives span a diversity of time periods and economic classes.[12] According to the San Jose Mercury News's Nora Villagran, the book has "a fascinating passage of places and people". She cited Chang's stories about the news anchor Connie Chung, the scientist Wen Ho Lee, the architect Maya Lin, the Air Force officer Ted Lieu, the author Amy Tan, the actress Anna May Wong, and the entrepreneur Jerry Yang.[19]

According to The Christian Science Monitor reviewer Terry Hong, the book is filled with obscure tidbits and thought-provoking ideas that would benefit even academics who were experts in Asian American history. She cited how Chang chronicles that since there were insufficient laundry services in their area, Chinese and white gold rush prospectors mailed their clothes to Hong Kong. Capitalizing on the situation, Chinese entrepreneurs founded local laundromats as they were willing to do the "women's work" white people were averse to doing. A second example, Hong said, was Chang's discussion of "Gold Mountain families", who were particularly prevalent in the relatives in Taishan, Guangdong. These family members no longer possessed employment capability because they enjoyed a high quality of life through remittances from their relatives who were working in the United States. According to Hong, a third example is Chang's inclusion of obscure narratives about Chinese American residents of the Deep South. Chang describes their extensive record of interracial marriages while they negotiated the stresses of not fitting neatly into the black or white racial categories.[2]

Reviewers had different opinions about the book's prose. Kimberly B. Marlowe of The Seattle Times said there is "a curious monotone to her prose in places", while Jill Wolfson of the San Jose Mercury News called it "clear, rich prose".[5][15] The Willamette Week's Steffen Silvis found the prose to be a "strong, engaging style", while Wisconsin State Journal's William R. Wineke called it "an easy dialogue that carries the reader along".[20][21] Silvis liked the book's numerous "interesting asides". He cited Chang's discussion of how chop suey was created and how Chang and Eng Bunker, the well-known "Siamese twins", bought slaves and settled in North Carolina.[20] The Los Angeles Times reviewer Anthony Day cited her story about Lue Gim Gong who invented several strains of fruit like that bore his name such as an orange and a grapefruit.[22] His orange could endure freezing temperatures and long-distance transport.[23] Repps Hudson, a book critic for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, said a "fascinating moment" in the book was Chang's chronicling of the Guangdong gold miners who sought to become rich during the California gold rush.[24]

Day of the Los Angeles Times said Chang's style is "straightforward and without grace" and that she narrates the tale "thoroughly and with confidence". He said she discusses but does not furnish the story's intense, poignant matter. She instead leaves it to those who review her book to reflect on the provided information.[22] The National Post columnist John Fraser formed a different view, calling the author a "retroactive emotionalist". He said the book has an "atmosphere of victimology" and a "tone of complaint" that frequently is "inappropriate and ahistorical". Fraser took issue with the tone because he said while it was difficult for transplants in 19th century America, being a resident of China in the 19th and 20th centuries was "infinitely rougher".[25] According to The Sacramento Bee's Will Evans, Chang describes "historical details or current events as if reporting on them—but there's an underlying pointed critique, a sense of injustice".[10] Evans interviewed University of California, Berkeley Asian American studies professor Ling-Chi Wang who said, "When you read this book, you can feel her emotion, her feelings about the Chinese American experience."[10]

Content

The book chronicles Chinese immigrants to the United States and their descendants.[26] The narrative starts in China, reviewing the Qing leadership's graft.[12] The United States experienced several waves of immigration from the Chinese.[27] The California gold rush in the 1850s followed by the first transcontinental railroad in the next decade triggered the first migration.[28] Around 100,000 men from China, who were primarily from impoverished villages, relocated to Gold Mountain to look for gold.[22][29] The male to female ratio was 12 to 1.[29] The gold rush ended and the Chinese laborers sought work. While enduring a rugged terrain and challenging winter conditions, over 50,000 Chinese laborers built the railroad and over 1,000 died before it was finished in 1869.[7][24] After railroad work dried up, the Chinese dispersed throughout the nation, taking on various jobs with low pay.[12][28] They were cooks, grocery store workers, herbalists, laundry workers, and waiters. They remitted a large portion of their wages to family members in China. Those family members led affluent lives, no longer needed to work, and demanded even more remittances.[28] The Chinese created Chinatowns in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and various American cities.[22]

At first, the predominant white population viewed the Chinese Americans as curiosities and did not bother them.[20] But as additional Chinese immigrated, the white population became more hateful owing to uneasiness at their success and fear that the Chinese would supplant them as workers.[4][20][30] After the golden spike signifying the end of construction for the transcontinental railroad was driven in 1867, many Chinese railroad workers immediately lost their jobs and sought work, inaugurating extensive competition between white people and the Chinese.[31] That led to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act which for around 75 years barred the Chinese from legally moving to the United States so they attempted other ways of getting in.[28][31] The 1906 San Francisco earthquake and subsequent fires obliterated public documents.[32] This allowed many of them to try the paper son approach where they used fake papers to prove they were born in China to American citizens.[28][32] The American government's reaction was to hold Chinese arrivals at the Angel Island Immigration Station in San Francisco.[27][28] Their detention was in conditions reminiscent of a jail.[28] The station, which 60,000 Chinese immigrants were held at, was created in 1910 and remained opened for 30 years.[27]

The immigrants from China largely were men, so prostitution, which the miners patronized, flourished. Tongs, secret societies, were formed as rival groups that provided Chinatown businessmen with sex slaves.[28] At the end of the 19th century, California experienced numerous riots against the Chinese.[12] By World War II, the Chinese in America who returned to China were shocked by the severe plight of residents there. At the same time, the people in China found those from America to be peculiar.[22] Since China and the United States were allies against the Japanese during World War II, Chinese Americans fared better. President Franklin D. Roosevelt asked Congress in 1943 to rescind the Chinese Exclusion Act and to let the Chinese become naturalized citizens. After the Communists' 1949 defeat of the Nationalists, Chinese Americans weathered worsening relations, particularly when China and the United States were adversaries during the Korean War.[7]

After the Communists took power in 1949, another wave of Chinese people moved to the United States.[22] Scholars overwhelmingly made up this stream of Chinese arrivals. Chung dubs them "intellectuals", a wide-ranging group encompassing doctors, scientists, and engineers. Before arriving, they had received a solid education from Chinese, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese educational institutions. They relocated to the United States to continue their education in the country's universities. Top-tier American university graduates inordinately were these arrivals' children. Chung argues that despite their accomplishments, they are still accused of being operatives for their homeland.[28] Joseph McCarthy in 1950 started a campaign to find communists and to determine how China got taken by the communists.[33]

Between 1850 and 1882, there had been about a quarter of a million Chinese in the country. Between 1882 and 1943 when the exclusion act was in effect, scores of thousands of Chinese were able to immigrate through deceitful means.[7] After the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 became law, numerous Chinese immigrated to the United States.[34] 100,000 entered in the 1960s, around a quarter of a million in the 1970s, over 450,000 in the 1980s, and over a half a million in the 1990s.[7]

In the 20th century's last 20 years after China's opening up, there was another wave of Chinese immigrants who were a mix of both the highly educated and those with minimal education.[27][35] Many of the latter came illegally into the United States and are employed in restaurants and clothing sweatshops managed by fellow Chinese Americans who take advantage of them.[7] Other Chinese Americans took on jobs during the 1990s dot-com boom.[12] Of the latest wave of arrivals, there were over 40,000 Chinese adoptees.[29] The book discusses contemporary stories such as that of Wen Ho Lee, a Los Alamos National Laboratory scientist who was wrongly implicated in espionage.[36][37] Titled "An Uncertain Future", the final chapter probes into the changing dynamics of racial groups' acceptance in America.[12] She concludes that China–United States relations deeply impact the plight of Chinese Americans irrespective of how long their ancestors have been in America.[7]

Themes

The Chinese Americans' struggle for success, its costs and tenuousness, are major themes in Chang's highly readable, panoramic history of Chinese American immigration from the Gold Mountain generation to the present.

A frequent theme is Chinese Americans being alternatively lauded and oppressed over the past century and a half.[1][12] Chang chronicles how society lauded how diligent Chinese workers were in constructing the first transcontinental railroad but then vilified as taking America's riches. When World War II was being fought, the Chinese were considered allies. But in the midst of the Korean War, the Chinese were charged with involvement in Communist espionage. Although they were called the model minority, they were labeled as clothing laborers who are indigent and lack education.[12]

During the gold rush era, the Chinese were forcibly displaced from their mining positions and stolen from. Sometimes, they were killed without any intervention from law enforcement. The 1887 Hells Canyon Massacre in Oregon caused numerous Chinese deaths. The Chinese were denied suffrage and they were disallowed from hospitals.[20] In California, Chinese-American children were not allowed to attend public schools. After the courts ruled against this practice, San Francisco created separate schools for Chinese children. In 1853, California passed the Criminal Proceeding Act which included Chinese Americans as part of the "degraded castes", which barred them from testifying in judicial proceedings involving white people.[39] The Naturalization Act of 1870 restricted naturalization to "white persons" and "aliens of African nativity and of persons of African descent", which barred Chinese-born immigrants from becoming citizens.[7] More contemporary events of Chang chronicles include the accusations against Wen Ho Lee and the Hainan Island incident in which an American surveillance aircraft went down over China. She said incidents like these inflame tensions from the American majority on Chinese Americans.[8] In response to critics who called the portrayal of the oppression unpatriotic, Chang said in an interview, "I see this as my love letter to America. Many people believe that to criticize the government is not patriotic, but I think it is the most patriotic thing you can do."[1][40]

Chang said that despite Chinese Americans' significant contributions to America, people still consider them and other Asian Americans to be outsiders owing to their skin color and their eye shape. She wrote of Asian Americans that "regardless of how many generations their families have been American, [most] can remember being asked, 'Where are you really from?'"[2] When Chang was in junior high, a white student asked her about her allegiance to the United States.[10] She cites the American figure skating Olympian Michelle Kwan, who was beaten by gold medalist Tara Lipinski in the 1998 Winter Olympics. MSNBC's headline was "American beats Kwan".[20] Another instance was some veterans' opposition to Maya Lin's design of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial—they called her a "gook"—despite her being American born.[7] According to Chang, in their obsession to become wealthy, Chinese immigrants neglected to develop political and social clout. Failing to connect and assist those of other backgrounds, they stay on the fringes of society owing to not sharing their background with others.[41]

Another theme is that Chinese Americans engaged in activism against oppression and were not meek foreign workers.[12][36] During the 1867 Chinese Labor Strike, Chinese American transcontinental railroad laborers seeking higher wages and a reduction in their work time participated in a general strike.[12][36] Plantation owners tried to hire Chinese workers to supplant Black slaves in the wake of the Civil War. When the owners breached the employment agreements, the Chinese workers enlisted attorneys to file lawsuits.[36] As a result, the Chinese no longer worked on Southern farms by 1915.[22] When the United States was transporting scrap metal to Japan during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Chinese Americans demonstrated for an embargo and garnered the public's approval. Joining with various ethnic communities, Chinese students at the University of California, Berkeley fought for and convinced the school to establish an ethnic studies curriculum.[12] When they were targeted with racially discriminatory taxes and laws, they demonstrated and filed lawsuits.[4] In the 1980s, Lowell High School sought to require Chinese students who sought admittance to have better grades than students of other demographics. The school board scrapped the change after the Chinese filed a lawsuit against it.[27] When the Los Alamos National Laboratory nuclear scientist Wen Ho Lee was wrongly charged with spying, a boycott against the lab prevailed.[32] Chang argues that the Chinese Americans' activism has challenged the misconception that they are "the model minority".[12] She said that the Chinese Americans' fights—alongside those of Native Americans, African Americans, and Latino Americans—contributed to molding American civil rights legislation.[4]

Reception

The Los Angeles Times reviewer Anthony Day praised the book for "tell[ing] one important part of the American story comprehensively", while the San Francisco Chronicle book critic Sanford D. Horwitt commended it for being an "absorbing, passionate story of the Chinese American experience".[22][27] In a positive review lauding the "exhaustive research" and "sheer writing ability", Jeff Guinn of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram wrote, "this engrossing account of Chinese-American struggles and triumphs is Pulitzer material".[43] Rachel Moloshok of Pennsylvania Legacies praised Chang's "nuanced and sensitive storytelling".[44] Repps Hudson, a book critic for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, extolled the book, writing, "Chang's book is valuable for the mirror it holds up to the United States. ... Chang's timely book deserves to be read in homes and schools because it documents well the struggles of one ethnic group to win its rightful place alongside others."[24]

The News & Observer book reviewer Roger Daniels judged the book to be "a fast-paced, sometimes breathless, well-written page-turner" that is "a good introduction to the topic".[7] The Christian Science Monitor Terry Hong found the book to be "a thought-provoking overview" that details Chinese Americans' cruciality to the history of the United States. Although she had several minor critiques, she concluded the book was an "exemplary achievement". Hong found Chang's use of the word "hapa" to be "problematic". Hong pointed out that Chang had contradictory statements as she said Chinese American residents of the 1960s South received "acceptance as honorary Caucasians". However, two pages afterwards she contradicts this by stating, "They could not earn full acceptance ... even as honorary Caucasians."[2] The Dallas Morning News book critic Jerome Weeks criticized the book for coming across as "a well-intentioned, generic textbook", citing how the "old Chinese proverb" cliché are the opening words of the initial chapter.[45]

Peter Schrag of The Washington Post penned a mixed review of the book, writing, "Chang has found a great subject, and her stories are well worth reading. But their very power begs for more depth, a clearer narrative line and a stronger, more confident sense of history." He said it "needs a stronger thread of hard data and analysis", pointing out the lack of information regarding the populace's size as Chang discusses how immigration ebbed and flowed. According to Schrag, she could have provided more than scant details about the Overseas Chinese and how they impacted American culture. He said she appears unclear about her story as she says on one page that there is a "new generation of Chinese American political activists" but two pages later writes that encountering governmental oppression in their homeland "caused many Chinese to focus their energies on economic achievement rather than politics". He lamented that Chang did not explain how most Chinese immigrants' being "intellectuals" impacted immigration policies and the population as a whole. He called her chronicling of major events in United States history like the Cold War, McCarthyism, and the financial misconduct during the Reagan period to be "simplistic" and to "make you a little uncomfortable with the rest of her account".[28]

Asianweek reviewer Sam Chu Lin dubbed the book "informative, thought-provoking and entertaining".[34] Jeff Wenger of The Asian Reporter called the book "undeniably a towering intellectual achievement", while the Northwest Asian Weekly found it to be "gripping and sobering".[46][47] Sian Wu of the International Examiner said that the book lacks a detailed assessment of why Chinese Americans are considered outsiders. According to Wu, the book may be "too fast of a read" for history enthusiasts because it is written under the premise that the reader is unfamiliar with the history of China and Chinese Americans. She concluded, however, that the wealth of obscure tales about Chinese Americans in "a voice that is both proud and perceptive" transform the book into "a fascinating look" at their accomplishments.[12]

The Economist penned a negative review of the book, including critiquing her lack of explanation for why the snakeheads who smuggle people to the United States are from a tiny Fujian district and her glossing over the details of the "staggering proposition" that in the gold rush era, numerous people in California sent their laundry to Hong Kong for cleaning.[48] The Choice book critic Karen J. Leong wrote a negative review of the book. She criticized how the book neglects ethnic Chinese newcomers not from China—such as those from Singapore and Latin America—by mainly emphasizing the Chinese residents of California. According to Leong, the book's most fleshed out parts are her discussion of her previous works on Qian Xuesen and the Second Sino-Japanese War rather than her recaps of researchers' and journalists' writings. Leong recommended that people consult the writers listed in the bibliography rather than read the book.[49]

Jeff Wenger of The Asian Reporter penned a mixed review of the book, calling the book "tend[ing] toward bias". He criticized Chang's use of the word "genocide" to describe the Seattle riot of 1886 in which white men attacked Chinese people. According to Wenger, while the actions were horrible, they were not even close to genocide. Wenger concluded that the book "would have been superior if it had been more consistently balanced, but, to its credit, it is always scholarly", calling it "invaluable for being deeper and broader on this important subject matter than anything else around".[42] Chinese American Forum book critic George Koo lauded the nearly 500-page book as being "far from dense" as Chang "skillfully compressed" many years of history, investigation, and interviews into "an epic that flows effortlessly and sweeps the reader along for an informative, fascinating and emotional ride".[33]

The Willamette Week's Steffen Silvis called it "a powerful book that leaves one breathless at times by the ignorance and barbarity of white American culture and law".[20] Barbara Chai of the Far Eastern Economic Review mostly praised the book, calling it "a comprehensive account" that discusses events in "an engaging and thought-provoking way". She criticized Chang's inclination to dwell on how Chinese Americans are oppressed because the stories and details are sufficient to entirely depict the narrative.[4] The Jakarta Post reviewer Rich Simons agreed, calling her "negativity and bitterness wearing" in her "almost unceasing criticism" of how the Chinese have fared in the United States.[29] In a mixed review, The Oregonian book critic Steve Duin said, "As a scrapbook of individual human odysseys, her history struggles to provide more than dimly-lit snapshots. As a chronicle of the timeless battle for civil liberties, the book is high, panoramic drama."[39]

In a positive review, Scott Nishimura of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram stated that Chang has "the eye of a historian and the rhythm of a mesmerizing storyteller" and covers international events across time "without bogging the story down in minutiae".[18] Peggy Spitzer Christoff of the Library Journal wrote, "Though some scholars might hope for more rigorous analysis, general readers will find many surprising aspects of the Chinese American experiences in the United States."[50] Booklist reviewer Brad Hooper said that for young adults the book is "a gripping narrative for teens' personal interest and for class discussion of America's diverse heritage".[51] Publishers Weekly said the author's "even, nuanced and expertly researched narrative evinces deep admiration for Chinese America, with good reason", while Book's Eric Wargo praised Chang's "superb" chronicling of Chinese American history.[52][53] Kirkus Reviews compared The Chinese in America to Lynn Pan's book Sons of the Yellow Emperor, which discusses similar material. The publication said The Chinese in America misses that book's "gravity and grace" but still is "a solid addition in a far-from-exhausted field".[54]

As part of an undergraduate course, Henry Yu, a history professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, had his students read The Chinese in America. Yu said that they enjoyed the book. The book describes a century and a half of oppression against the Chinese including the Chinese Exclusion Act and Wen Ho Lee's case. Yu said, "The early parts of the book, where she talks about the early histories, they piss you off. That's a valuable thing, teaching-wise. I want my students to be pissed off."[55]

Adaptations

The audiobook version of The Chinese in America was released in 2005. Performed by Nancy Wu, the 17-hour-long audiobook is unabridged.[56] Susan G. Baird of the Library Journal praised Wu's "beautiful voice and accent as she speaks in English and pronounces Chinese words and names", while Kliatt's Sunnie Grant said Wu "does an admirable job in reading the text".[17][56] AudioFile had a mixed review of the reading, praising Wu's performance for being "sensitive, even, and well paced" but finding "the flat tonality" used for several Chinese names and phrases to be "somewhat distracting".[57]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Eng, Monica (2005-02-06). "Flameout: Best-Selling Author Iris Chang Had It All. Then Something Went Terribly Wrong". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 2354294644. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Hong, Terry (2003-05-08). "Fu Manchu doesn't live here. The struggle and triumph of Chinese-Americans are an integral part of US history". The Christian Science Monitor. ProQuest 1802777358. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ Hong, Terry (2004-11-18). "Living With Loss". AsianWeek. p. 13. ProQuest 367341809.

- ^ a b c d e Chai, Barbara (2003-08-28). "Overdue History: The Chinese in America finally have a comprehensive chronicle of their struggles and achievements". Far Eastern Economic Review. Vol. 166, no. 34. pp. 66–67. Factiva feer000020030821dz8s0000s.

- ^ a b Marlowe, Kimberly B. (2003-05-18). "Chinese Americans' long journey - Iris Chang sets the record straight on the struggles and achievements of a vital ethnic group". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b Eck, Michael (2004-04-11). "Chinese History in America a 'Cyclical Journey'". Times Union. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Daniels, Roger (2003-06-22). "Tragedy and triumph: Asians walked a rocky path into America". The News & Observer. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Wenger, Jeff (2003-05-20). "Iris Chang discusses Chinese in America". The Asian Reporter. p. 21. ProQuest 367947981.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (2004-11-12). "Iris Chang Is Dead at 36; Chronicled Rape of Nanking". The New York Times. ProQuest 92748499. Archived from the original on 2024-06-27. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e Evans, Will (2003-06-19). "Iris Chang's new epic seeks to set the record straight" (pages 1 and 2). The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original (pages 1 and 2) on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Wu, Esther (2003-10-16). "Author felt compelled to offer untold stories". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wu, Sian (2003-05-21). "An American Story: The history of Chinese immigrants". International Examiner. p. 12. ProQuest 367752919.

- ^ Gare, Shelley (2007-12-08). "Brought down by history". The Australian. ProQuest 356056582. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ "Chang, Iris". ProQuest Biographies. 2022. ProQuest 2776684279.

- ^ a b Wolfson, Jill (2003-04-27). "Epic Explores Being Chinese in the u.s." San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ Magida, Arthur J. (2004-11-17). "She forced us to face history's horrors". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Grant, Sunnie (November 2005). "The Chinese in America". Kliatt. Vol. 39, no. 6. p. 52. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ a b Nishimura, Scott (2003-06-22). "An American Story: The history of Chinese emigration is a powerful, moving tale" (pages 1 and 2). Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original (pages 1 and 2) on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Villagran, Nora (2003-06-03). "Chinese-American Writer Tells History of Human Rights". San Jose Mercury News. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Silvis, Steffen (2003-05-21). "Rape of Nanking author Iris Chang examines the overlooked personal tragedies of Chinese living in America. Chinese Whispers". Willamette Week. p. 59. ProQuest 368308967.

- ^ Wineke, William R. (2003-04-27). "Despite Decades Upon Decades of Pain, Injustices, Tears and Fears, the Chinese in America ... Press On". Wisconsin State Journal. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Day, Anthony (2003-05-09). "The Chinese immigrant story, all part of the American epic". Los Angeles Times. ProQuest 421999893. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ Tan, Cheryl Lu-Tien (2003-05-06). "Helping us all understand: Iris Chang's book tries to shed new light on Chinese-Americans" (pages 1 and 2). The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original (pages 1 and 2) on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Hudson, Repps (2003-04-27). "Story of Chinese in America reflects a flaw in our national character". St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Fraser, John (2003-07-12). "A major education in victimology". National Post. ProQuest 330106811. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Best-selling author Iris Chang found dead in her car". Times Herald-Record. Associated Press. 2004-11-11. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Horwitt, Sanford D. (2003-05-11). "The threat of success / Chinese immigrants have fought 150 years of discrimination". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schrag, Peter (2003-05-18). "Journey to the West. The Chinese in America: A Narrative History". The Washington Post. ProQuest 2263766112.

- ^ a b c d Simons, Rich (2004-04-04). "A colorful, sometimes sad story". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ Guinn, Jeff (2003-07-27). "Author gives America's melting pot a good stir". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Sarasota Herald-Tribune.

- ^ a b Yamaguchi, David (2017-09-14). "Eclipse Chasing, Part 2". North American Post. ProQuest 2199222204. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c Benson, Heidi (2003-05-08). "From China to Gold Mountain / San Jose writer offers new perspective on immigrant history". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b Koo, George (2003-07-01). "The Chinese in America: A Narrative History". Chinese American Forum. Vol. 19, no. 1. pp. 44–45. ISSN 0895-4690. EBSCOhost 11149763.

- ^ a b Lin, Sam Chu (2003-03-26). "APA Author Sheds New Light on Chinese American Experience". Asianweek. p. 10. ProQuest 367568734.

- ^ Conan, Neal (2003-05-07). "Interview: Author Iris Chang discusses the Chinese immigration experience during the last two centuries and her book, "The Chinese in America"". Talk of the Nation. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b c d Eng, Monica (2004-06-02). "Illinois author Iris Chang follows the remarkable arc of Chinese-American history: 'My love letter to America'" (pages 1 and 2). Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 2346726620. Archived from the original (pages 1 and 2) on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Zhang, Jennifer (2003-06-18). "Best selling author gives Senior Center book talk". Cupertino Courier. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ "Our Editors Recommend". San Francisco Chronicle. 2003-05-25. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ a b Duin, Steve (2003-05-18). "Book Review. Nonfiction Review: The Chinese in America". The Oregonian. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ Eng, Monica (2004-11-15). "Iris Chang: Passionate and engaged". Chicago Tribune. ProQuest 2328696989. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ "Community's strength lies in coalitions". Northwest Asian Weekly. 2003-06-06. p. 2. ProQuest 362689380.

- ^ a b Wenger, Jeff (2003-08-19). "Chang offers sensitive, scholarly Chinese in America". The Asian Reporter. p. 14. ProQuest 368121461.

- ^ Guinn, Jeff (2003-06-18). "Our book editors' Top 20 picks" (pages 1 and 2). Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original (pages 1 and 2) on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Moloshok, Rachel (May 2012). "The Chinese in America: A Narrative History". Pennsylvania Legacies. Vol. 12, no. 1. p. 38. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ Weeks, Jerome (2003-10-15). "Detailed history - Iris Chang's grit punctuates roaming 'Chinese in America'". The Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.

- ^ Wenger, Jeff (2004-11-23). "From the Wild West; Remembering Iris Chang". The Asian Reporter. p. 7. ProQuest 368144534.

- ^ "Iris Chang deepened our view of history". Northwest Asian Weekly. 2004-11-20. p. 2. ProQuest 362690884.

- ^ "A ragged tale of riches; Chinese immigration". The Economist. Vol. 367, no. 8329. 2003-06-21. p. 76US. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ Leong, Karen J. (October 2003). "The Chinese in America : a narrative history". Choice. Vol. 41, no. 2. doi:10.5860/CHOICE.41-1108.

- ^ Christoff, Peggy Spitzer (2003-05-01). "Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America: a Narrative History". Library Journal. Vol. 128, no. 8. p. 134. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ Hooper, Brad (2003-04-01). "Chang, Iris. The Chinese in America: a Narrative History". Booklist. Vol. 99, no. 15. p. 1354. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ "The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. (Nonfiction)". Publishers Weekly. Vol. 250, no. 18. 2003-05-05. p. 216. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ Wargo, Eric (May–June 2003). "The Chinese in America: a Narrative History". Book. pp. 79+. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ "The Chinese in America: A Narrative History. (Nonfiction)". Kirkus Reviews. Vol. 71, no. 6. 2003-03-15. p. 437. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ Ito, Robert (2005-05-18). "Leaving the Atrocity Exhibit". The Village Voice. p. 46. ProQuest 232259666.

- ^ a b Baird, Susan G. (2005-10-01). "The Chinese in America: A Narrative History". Library Journal. Vol. 130, no. 16. p. 121. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30 – via Gale.

- ^ "The Chinese in America". AudioFile. August–September 2005. Archived from the original on 2024-06-30. Retrieved 2024-06-30.