Temple of Confucius, Qufu

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hall of Great Perfection (Dacheng Hall), the main sanctuary of the Temple of Confucius | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Qufu, Shandong, China | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of | Temple and Cemetery of Confucius and the Kong Family Mansion in Qufu | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (iv), (vi) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Reference | 704 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Inscription | 1994 (18th Session) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 35°35′48″N 116°59′3″E / 35.59667°N 116.98417°E | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 孔庙 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 孔廟 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

The Temple of Confucius (Chinese: 孔廟; pinyin: Kǒng miào) in Qufu, Shandong Province, is the largest and most renowned temple of Confucius in East Asia.

Since 1994, the Temple of Confucius has been part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site "Temple and Cemetery of Confucius and the Kong Family Mansion in Qufu".[1] The two other parts of the site are the nearby Kong Family Mansion, where the main-line descendants of Confucius lived, and the Cemetery of Confucius a few kilometers to the north, where Confucius and many of his descendants have been buried. Those three sites are collectively known in Qufu as San Kong (三孔), i.e. "The Three Confucian [sites]".

There is a 72-meter-tall statue of Confucius made of brass and reinforced with steel. Qufu, Shandong province, is the birthplace of the ancient Chinese educator and philosopher.

History

Within two years after the death of Confucius, his former house in Qufu was already consecrated as a temple by the Duke of Lu.[2] In 205 BC, Emperor Gao of the Han dynasty was the first emperor to offer sacrifices to the memory of Confucius in Qufu. He set an example for many emperors and high officials to follow. Later, emperors would visit Qufu after their enthronement or on important occasions such as a successful war. In total, 12 different emperors paid 20 personal visits to Qufu to worship Confucius. About 100 others sent their deputies for 196 official visits. The original three-room house of Confucius was removed from the temple complex during a rebuilding undertaken in 611 AD. In 1012 and in 1094, during the Song dynasty, the temple was extended into a design with three sections and four courtyards, around which eventually more than 400 rooms were arranged. Fire and vandalism destroyed the temple in 1214, during the Jin dynasty. It was restored to its former extent by the year 1302 during the Yuan dynasty. Shortly thereafter, in 1331, the temple was framed in an enclosure wall modelled on the Imperial palace.

After another devastation by fire in 1499, the temple was finally restored to its present scale. In 1724, yet another fire largely destroyed the main hall and the sculptures it contained. The subsequent restoration was completed in 1730. Many of the replacement sculptures were damaged and destroyed during the Cultural Revolution in 1966. In total, the Temple of Confucius has undergone 15 major renovations, 31 large repairs, and numerous small building measures.

Another main Confucius Temple was built in Quzhou by the southern branch of the Confucius family.

Description

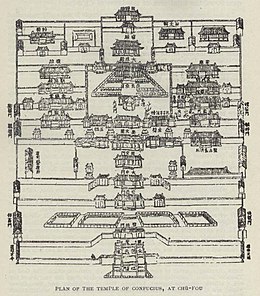

The temple complex is among the largest in China, it covers an area of 16,000 square metres and has a total of 460 rooms. Because the last major redesign following the fire in 1499 took place shortly after the building of the Forbidden City in the Ming dynasty, the architecture of the Temple of Confucius resembles that of the Forbidden City in many ways.

The main part of the temple consists of nine courtyards arranged on a central axis, which is oriented in the north–south direction and is 1.3 km in length. The first three courtyards have small gates and are planted with tall pine trees, they serve an introductory function. The first (southernmost) gate is named "Lingxing Gate" (欞星門) after a star in the Great Bear constellation, the name suggests that Confucius is a star from heaven. The buildings in the remaining courtyards form the heart of the complex. They are impressive structures with yellow roof-tiles (otherwise reserved for the emperor) and red-painted walls, they are surrounded by dark-green pine trees to create a color contrast with complementary colors.

The main structures of the temple are:

- Lingxing Gate (欞星門)

- Shengshi Gate (聖時門)

- Hongdao Gate (弘道門)

- Dazhong Gate (大中門)

- Thirteen Stele Pavilions (十三碑亭)

- Dacheng Gate (大成門)

- Kuiwen Hall (奎文閣, built in 1018, restored in 1504 during the Ming dynasty and in 1985)

- Xing Tan Pavilion (杏壇, Apricot Platform)

- De Mu Tian Di Arch

- Liangwu (兩廡)

- Dacheng Hall (大成殿, built in the Qing dynasty)

- Resting Hall (寢殿, dedicated to Confucius' Wife)

Dacheng Hall

The Dacheng Hall (Chinese: 大成殿; pinyin: Dàchéng diàn), whose name is usually translated as the Hall of Great Perfection or the Hall of Great Achievement, is the architectural center of the present-day complex. The hall covers an area of 54 by 34 m and stands slightly less than 32 m tall. It is supported by 28 richly decorated pillars, each 6 m high and 0.8 m in diameter and carved in one piece out of local rock. The 10 columns on the front side of the hall are decorated with coiled dragons. It is said that these columns were covered during visits by the emperor in order not to arouse his envy. Dacheng Hall served as the principal place for offering sacrifices to the memory of Confucius. It is also said to be one of the most beautiful views of Confucius Temple.

- Façade of Dacheng Hall

- One of the dragon pillars in front of Dacheng Hall

Apricot Platform

In the center of the courtyard in front of Dacheng Hall stands the Xing Tan Pavilion (simplified Chinese: 杏坛; traditional Chinese: 杏壇; pinyin: Xìng Tán), or the Apricot Platform. It commemorates Confucius teaching his students under an apricot tree. Each year at Qufu and at many other Confucian temples a ceremony is held on September 28 to commemorate Confucius' birthday.

Stele pavilions

A large number of stone stelae are located on the premises of the Temple of Confucius. A recent book on Confucian stelae in Qufu catalogs around 500 such monuments on the temple's grounds,[3] noting that the list is far from complete.[4] The steles commemorate repeated rebuildings and renovations of the temple complex, contain texts extolling Confucius and imperial edicts granting him new honorary titles. While most of these tablets were originally associated with the Temple of Confucius, some have been moved to the temple's grounds for safekeeping from other sites in Qufu in modern times.[5]

The inscriptions on the stelae are mostly in Chinese, but some of the Yuan dynasty and Qing dynasty stelae also have texts, respectively, in Middle Mongolian (using the 'Pags-Pa script) and Manchu.

Some of the most important imperial stelae are concentrated in the area known as the "Thirteen Stele Pavilions" (十三碑亭, Shisan Bei Ting). These 13 pavilions are arranged in two rows in the narrow courtyard between the Pavilion of the Star of Literature (奎文閣, Kuiwen Ge) in the south and the Gates of Great Perfection (大成門, Dacheng Men) in the north.

The northern row consists of five pavilions, each of which houses one large stele carried by a giant stone tortoise (bixi) and crowned with dragons; they were installed during the Kangxi, Yongzheng and Qianlong eras of the Qing dynasty (between Kangxi 22 and Qianlong 13, i.e. A.D. 1683–1748). These imperial stelae stand 3.8 to 4 m tall, their turtles being up to 4.8 m long. They weigh up to 65 tons (including the stele, the bixi turtle, and the plinth under it).[6]

The southern row consists of eight pavilions, housing smaller steles, several in each. Four of them house stelae from the Jurchen Jin dynasty (1115-1234) and the Mongol Yuan dynasty; the others, from the Qing dynasty.[7]

A large number of smaller tablets of various eras, without bixi pedestals, are lined in the open air in "annexes" around the four corners of the Thirteen Stele Pavilions area.[8]

Four important tortoise-borne imperial stelae from the Ming dynasty can be found in the courtyard south of the Star of Literature Pavilion. This area has two stele pavilions. The eastern pavilion houses a stele from Year 4 of the Hongwu era (1371), designating deities associated with geographical directions etc. The western pavilion contains a stele from Year 15 of the Yongle era (1417), commemorating a renovation of the temple. The other two stelae are in the open air: a Year 4 of the Chenghua era (1468) stele in front of the eastern pavilion, and Year 17 of the Hongzhi era (1504) stele in front of the western pavilion, also commemorating temple repair projects. Dozens more of smaller, turtle-less stelae are located in this area as well.[9]

- Tortoise-borne stelae in the Temple of Confucius

- Taiping Xingguo 8 (983)

- Cheng'an 8 (1197)

- Dade 5 (1301)

- Dade era (1297-1307) (left); Dade 11 (1307) (right); Late Zhiyuan 5 (1339) (center)

- Hongwu 4 (1371)

- Yongle 15 (1417)

- Chenghua 4 (1468)

- Hongzhi 17 (1504)

- Shunzhi 8 (1651)

- Kangxi 7 (1668)

- Kangxi 15 (1676; right), Kangxi 21 (1682; left)

- Kangxi 22 (1683)

- Kangxi 25 (1686)

- Yongzheng 8 (1730)

- Yongzheng 8 (1730)

- Yongzheng 8 (1730)

- Qianlong 13 (1748)

See also

- Mount Ni near Qufu, traditionally believed to be the birthplace of Confucius

- Temple of Yan Hui, another temple in Qufu built in honor of Confucius' favorite student

- Zoucheng, a nearby city with the temple of the "second sage" Mencius

- Kong Family Mansion, residence of Confucius' direct descendants next to the temple

- Temple of Zengzi 曾廟

- Mencius's sites- Meng family mansion 孟府, Temple of Mencius 孟廟, and Cemetery of Mencius 孟林

Notes

- ^ "Temple and Cemetery of Confucius and the Kong Family Mansion in Qufu". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Advisory Body Evaluation of the Temple of Confucius, the Cemetery of Confucius, and the Kong Family Mansion in Qufu (ICOMOS) (Report). ICOMOS. 1994. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Luo Chenglie (2001), list on pp. 1110-1128

- ^ Luo Chenglie (2001), p. 1 (Compiler's preface)

- ^ E.g., some stelae found in Jiuxian village, which was the site of the Qufu county seat during the Song, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties.

- ^ The list of stelae in this row in Luo Chenglie (2001), p. 1119, and the individual entries for the five stelae listed there. The weight information, page 10 (end note 1) in the Compiler's preface.

- ^ The list of stelae in these pavilions in Luo Chenglie (2001), p. 1119-1122, and the individual entries for the five stelae listed there.

- ^ The list of stelae in these four areas in Luo Chenglie (2001), p. 1122-1126.

- ^ The list of stelae in these four areas in Luo Chenglie (2001), p. 1110-1114.

References

- Confucius; Slingerland, Edward Gilman (2003), Confucius analects: with selections from traditional commentaries, Hackett Publishing, ISBN 0-87220-635-1

- 孔繁银 (Kong Fanyin) (2002), 曲阜的历史名人与文物 (Famous people and cultural relics of Qufu's history), 齐鲁书社 (Jinlu Shushe), ISBN 7-5333-0981-2

- 骆承烈 (Luo Chenglie), ed. (2001), 石头上的儒家文献-曲阜的碑文录 (Confucian writing in stone: a catalog of inscriptions on Qufu's steles), vol. 1, 2, 齐鲁书社 (Jinlu Shushe), ISBN 7-5333-0781-X. Continuous page numbering through both volumes. Table of contents is available at https://web.archive.org/web/20110723030617/http://www.book110.net/book/466/0466441.htm