Taxi Driver

| Taxi Driver | |

|---|---|

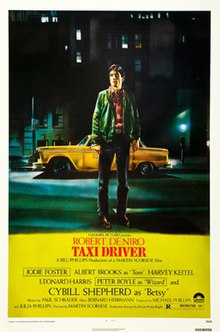

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Martin Scorsese |

| Written by | Paul Schrader |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Chapman |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Bernard Herrmann |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.9 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $28.6 million[5] |

Taxi Driver is a 1976 American neo-noir psychological drama film[6][7] directed by Martin Scorsese, written by Paul Schrader, and starring Robert De Niro, Jodie Foster, Cybill Shepherd, Harvey Keitel, Peter Boyle, Leonard Harris, and Albert Brooks in his first film role. Set in a morally decaying New York City following the Vietnam War, the film follows Travis Bickle (De Niro), a veteran Marine and taxi driver, and his deteriorating mental state as he works nights in the city.

With The Wrong Man (1956) and A Bigger Splash (1973) as inspiration, Scorsese wanted the film to feel like a dream to audiences[citation needed]. Filming began in the summer of 1975 in New York City, with actors taking pay cuts to ensure that the project could be completed on a low budget of $1.9 million. Production concluded that same year. Bernard Herrmann composed for the film what would be his final score; the music was finished just hours before his death, and the film is dedicated to him.

Theatrically released by Columbia Pictures on February 8, 1976, the film was critically and commercially successful despite generating controversy both for its graphic violence in the climactic ending and for the casting of then 12-year-old Foster as a child prostitute. The film received numerous accolades including the Palme d'Or at the 1976 Cannes Film Festival and four nominations at the 49th Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Actor (for De Niro), and Best Supporting Actress (for Foster).

Although Taxi Driver generated further controversy for inspiring John Hinckley Jr.'s attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in 1981, the film has remained popular. It is considered one of the greatest films ever made and one of the most culturally significant and inspirational of its time, garnering cult status.[8] In 2022, Sight & Sound named it the 29th-best film ever in its decennial critics' poll, and the 12th-greatest film of all time on its directors' poll, tied with Barry Lyndon. In 1994, the film was considered "culturally, historically, or aesthetically" significant by the U.S. Library of Congress and was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.

Plot

In New York City, Vietnam veteran Travis Bickle takes a job as a night shift taxi driver to cope with his chronic insomnia and loneliness, frequenting adult movie theaters and keeping a diary in which he consciously attempts to include aphorisms such as "you're only as healthy as you feel." He becomes disgusted with the crime and urban decay that he witnesses in the city and dreams about getting "the scum off the streets."

Travis becomes infatuated with Betsy, a campaign volunteer for Senator and presidential candidate Charles Palantine. Travis enters the campaign office where she works and asks her out for coffee, to which she agrees. Betsy agrees to go on another date with him. During their date, Travis takes Betsy to a porn theater, which repulses her into leaving. He attempts to reconcile with her, but to no avail. Enraged, he storms into the campaign office where she works and then proceeds to berate her before being kicked out of the office.

Experiencing an existential crisis and seeing various acts of prostitution throughout the city, Travis confides in a fellow taxi driver nicknamed Wizard about his violent thoughts. However, Wizard dismisses them and assures him that he will be fine. To find an outlet for his rage, Travis follows an intense physical training regimen. He gets in contact with black market gun dealer Easy Andy, and buys four handguns. At home, Travis practices drawing his weapons, even creating a quick-draw rig hidden in his sleeve. He begins attending Palantine's rallies to scope out his security. One night, Travis shoots and kills a black man attempting to rob a convenience store run by a friend of his.

On his trips around the city, Travis regularly encounters Iris, a 12-year-old child prostitute. Fooling her pimp and abusive lover, Sport, into thinking he wants to solicit her, Travis meets with her in private and tries to persuade her to stop prostituting herself. Soon after, Travis cuts his hair into a mohawk and attends a public rally where he plans to assassinate Palantine. However, Secret Service agents see Travis putting his hand inside his jacket and approach him, escalating into a foot chase. Travis escapes pursuit and makes it home undetected.

That evening, Travis drives to the brothel where Iris works to kill Sport. He enters the building and shoots Sport and one of Iris's clients, a mafioso. Travis is shot several times, but manages to kill the two men. He then brawls with the bouncer, whom he manages to stab through the hand with his knife located in his shoe and finish off with a gunshot to the head. Travis attempts to commit suicide, but is out of bullets. Severely injured, he slumps on a couch next to a sobbing Iris. As police respond to the scene, a delirious Travis imitates shooting himself in the head using his finger.

Travis goes into a coma due to his injuries. He is heralded by the press as a heroic vigilante and not prosecuted for the murders. He receives a letter from Iris's parents in Pittsburgh, who thank him and reveal that she is safe and attending school back home.

After recovering, Travis grows his hair out and returns to work, where he encounters Betsy as a fare; they interact cordially, with Betsy saying she followed his story in the newspapers. Travis drops her at home, and declines to take her money, driving off with a smile. He suddenly becomes agitated after noticing something in his rear-view mirror, but continues driving into the night.

Cast

- Robert De Niro as Travis Bickle

- Jodie Foster as Iris Steensma

- Cybill Shepherd as Betsy

- Harvey Keitel as Matthew "Sport" Higgins

- Albert Brooks as Tom

- Leonard Harris as Senator Charles Palantine

- Peter Boyle as "Wizard"

- Steven Prince as "Easy Andy", the Gun Salesman

- Martin Scorsese as "Passenger Watching Silhouette"/Man Outside Palantine Headquarters

- Harry Northup as "Doughboy"

- Victor Argo as Melio, the Bodega Clerk

- Joe Spinell as The Personnel Officer

Production

Development

Martin Scorsese has stated that it was Brian De Palma who introduced him to Paul Schrader,[10] and Taxi Driver arose from Scorsese's feeling that movies are like dreams or drug-induced reveries. He attempted to evoke within the viewer the feeling of being in a limbo state between sleeping and waking. Scorsese cites Alfred Hitchcock's The Wrong Man (1956) and Jack Hazan's A Bigger Splash (1973) as inspirations for his camerawork in the movie. The film gives the famous Satyajit Ray's protagonist Narasingh (played by Soumitra Chatterjee) in Abhijan (1962) as a direct influence for the character of the cynical cab driver Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro).[11] Before Scorsese was hired, John Milius and Irvin Kershner were considered to helm the project.[12] In writing the script, Schrader drew inspiration from the diaries of Arthur Bremer, who shot presidential candidate George Wallace in 1972,[13] as well as from the Harry Chapin song "Taxi", which is about an old girlfriend getting into a cab.[14] For the ending of the story, in which Bickle becomes a media hero, Schrader was inspired by Sara Jane Moore's attempted assassination of President Gerald Ford, which resulted in her being on the cover of Newsweek.[15]

Schrader also used himself as inspiration. In a 1981 interview with Tom Snyder on The Tomorrow Show, he related his experience of living in New York City while battling chronic insomnia, which led him to frequent pornographic bookstores and theaters because they remained open all night. Following a divorce and a breakup with a live-in girlfriend, he spent a few weeks living in his car. After visiting a hospital for a stomach ulcer, Schrader wrote the screenplay for Taxi Driver in "under a fortnight." He states, "The first draft was maybe 60 pages, and I started the next draft immediately, and it took less than two weeks." Schrader recalls, "I realized I hadn't spoken to anyone in weeks [...] that was when the metaphor of the taxi occurred to me. That is what I was: this person in an iron box, a coffin, floating around the city, but seemingly alone." Schrader decided to make Bickle a Vietnam vet because the national trauma of the war seemed to blend perfectly with Bickle's paranoid psychosis, making his experiences after the war more intense and threatening.[16] Two drafts were written in ten days.[17] Pickpocket, a film by the French director Robert Bresson, was also cited as an influence.[18]

In Scorsese on Scorsese, Scorsese mentions the religious symbolism in the story, comparing Bickle to a saint who wants to cleanse or purge both his mind and his body of weakness. Bickle attempts to kill himself near the end of the movie as a tribute to the samurai's "death with honor" principle.[11] Dustin Hoffman was offered the role of Travis Bickle but turned it down because he thought that Scorsese was "crazy".[19] Al Pacino and Jeff Bridges were also considered for Travis Bickle.[12]

Pre-production

While preparing for his role as Bickle, De Niro was filming Bernardo Bertolucci's 1900 in Italy. According to Boyle, he would "finish shooting on a Friday in Rome ... get on a plane ... [and] fly to New York." De Niro obtained a taxi driver's license, and when on break, would pick up a taxi and drive around New York for a couple of weeks before returning to Rome to resume filming 1900. Although Robert DeNiro had already starred in Godfather II (1974), he was only recognized one time while driving a cab in New York City.[20] De Niro apparently lost 16 kilograms (35 pounds) and listened repeatedly to a taped reading of the diaries of criminal Arthur Bremer. When he had time off from shooting 1900, De Niro visited an army base in Northern Italy and tape-recorded soldiers from the Midwestern United States, whose accents he thought might be appropriate for Travis's character.[21]

Scorsese brought in the film title designer Dan Perri to design the title sequence for Taxi Driver. Perri had been Scorsese's original choice to design the titles for Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore in 1974, but Warner Bros would not allow him to hire an unknown designer. By the time Taxi Driver was going into production, Perri had established his reputation with his work on The Exorcist, and Scorsese was now able to hire him. Perri created the opening titles for Taxi Driver using second unit footage which he color-treated through a process of film copying and slit-scan, resulting in a highly stylised graphic sequence that evoked the "underbelly" of New York City through lurid colors, glowing neon signs, distorted nocturnal images, and deep black levels. Perri went on to design opening titles for a number of major films after this, including Star Wars (1977) and Raging Bull (1980).[22][23]

Filming

Columbia Pictures gave Scorsese a budget of $1.3 million in April 1974.[10] On a budget of only $1.9 million, various actors took pay cuts to bring the project to life. De Niro and Cybill Shepherd received only $35,000 to make the film, while Scorsese was given $65,000. Overall, $200,000 of the budget was allocated to performers in the movie.[3][24]

Taxi Driver was shot during a New York City summer heat wave and sanitation strike in 1975. The film ran into conflict with the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) due to its violence. Scorsese de-saturated the colors in the final shootout, which allowed the film to get an R rating. To capture the atmospheric scenes in Bickle's taxi, the sound technicians would get in the trunk while Scorsese and his cinematographer, Michael Chapman, would ensconce themselves on the back seat floor and use available light to shoot. Chapman later admitted the filming style was heavily influenced by New Wave filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard and his cinematographer Raoul Coutard, as the crew did not have the time or money to do "traditional things".[25] When Bickle decides to assassinate Senator Palantine, he cuts his hair into a mohawk. This detail was suggested by actor Victor Magnotta, a friend of Scorsese's who had a small role as a Secret Service agent and had served in Vietnam. Scorsese later noted that Magnotta told them that, "in Saigon, if you saw a guy with his head shaved—like a little Mohawk—that usually meant that those people were ready to go into a certain Special Forces situation. You didn't even go near them. They were ready to kill."[13]

Filming took place on New York City's West Side, at a time when the city was on the brink of bankruptcy. According to producer Michael Phillips, "the whole West Side was bombed out. There really were row after row of condemned buildings and that's what we used to build our sets [...] we didn't know we were documenting what looked like the dying gasp of New York."[26] The tracking shot over the shootout scene, filmed in an actual apartment, took three months of preparation; the production team had to cut through the ceiling to shoot it.[27]

Music

| Taxi Driver: Original Soundtrack Recording | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | |

| Released | May 19, 1998 |

| Recorded | December 22 and 23, 1975[28] |

| Genre | Soundtrack |

| Length | 61:33 |

| Label | Arista |

| Producer | Michael Phillips, Neely Plumb |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

Bernard Herrmann previously scored De Palma's Obsession and De Palma introduced Herrmann to Scorsese.[30] The music by Herrmann was his final score before his death on December 24, 1975, several hours after Herrmann completed the recording for the soundtrack, and the film is dedicated to his memory. Scorsese, a long-time admirer of Herrmann, had particularly wanted him to compose the score; Herrmann was his "first and only choice". Scorsese considered Herrmann's score of great importance to the success of the film: "It supplied the psychological basis throughout."[31] The album The Silver Tongued Devil and I from Kris Kristofferson was used in the film, following Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1974) where Kristofferson played a supporting role.[32] Jackson Browne's "Late for the Sky" is also featured.

Controversies

Casting of Jodie Foster

Some critics showed concern over 12-year-old Foster's presence during the climactic shoot-out.[33] Foster said that she was present during the setup and staging of the special effects used during the scene; the entire process was explained and demonstrated for her, step by step. Moreover, Foster said, she was fascinated and entertained by the behind-the-scenes preparation that went into the scene. In addition, before being given the part, Foster was subjected to psychological testing, attending sessions with a UCLA psychiatrist, to ensure that she would not be emotionally scarred by her role, in accordance with California Labor Board requirements monitoring children's welfare on film sets.[34][35]

Additional concerns surrounding Foster's age focus on the role she played as Iris, a prostitute. Years later, she confessed how uncomfortable the treatment of her character was on set. Scorsese did not know how to approach different scenes with the actress. The director relied on Robert De Niro to deliver his directions to the young actress. Foster often expressed how De Niro, in that moment, became a mentor to her, stating that her acting career was highly influenced by the actor's advice during the filming of Taxi Driver.[36]

John Hinckley Jr.

Taxi Driver formed part of the delusional fantasy of John Hinckley Jr.[37] that triggered his attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in 1981, an act for which he was found not guilty by reason of insanity.[38] Hinckley stated that his actions were an attempt to impress Foster, on whom Hinckley was fixated, by mimicking Travis's mohawked appearance at the Palantine rally. His attorney concluded his defense by playing the movie for the jury.[39][40] When Scorsese heard about Hinckley's motivation behind his assassination attempt, he briefly thought about quitting film-making as the association brought a negative perception of the film.[41]

MPAA rating

The climactic shoot-out was considered intensely graphic by some critics, who even considered giving the film an X rating.[42] The film was booed at the Cannes Film Festival for its graphic violence.[43] To obtain an R rating, Scorsese had the colors desaturated, making the brightly colored blood less prominent. In later interviews, Scorsese commented that he was pleased by the color change and considered it an improvement over the original scene.[44] However, in the special-edition DVD, Michael Chapman, the film's cinematographer, expresses regret about the decision and the fact that no print with the unmuted colors exists anymore, as the originals had long since deteriorated.

Themes and interpretations

Roger Ebert has written of the film's ending:

There has been much discussion about the ending, in which we see newspaper clippings about Travis's "heroism" of saving Iris, and then Betsy gets into his cab and seems to give him admiration instead of her earlier disgust. Is this a fantasy scene? Did Travis survive the shoot-out? Are we experiencing his dying thoughts? Can the sequence be accepted as literally true? ... I am not sure there can be an answer to these questions. The end sequence plays like music, not drama: It completes the story on an emotional, not a literal, level. We end not on carnage but on redemption, which is the goal of so many of Scorsese's characters.[45]

James Berardinelli, in his review of the film, argues against the dream or fantasy interpretation, stating:

Scorsese and writer Paul Schrader append the perfect conclusion to Taxi Driver. Steeped in irony, the five-minute epilogue underscores the vagaries of fate. The media builds Bickle into a hero, when, had he been a little quicker drawing his gun against Senator Palantine, he would have been reviled as an assassin. As the film closes, the misanthrope has been embraced as the model citizen—someone who takes on pimps, drug dealers, and mobsters to save one little girl.[46]

In the 1990 LaserDisc audio commentary (included on the [DVD] and Blu-ray), Scorsese acknowledged several critics' interpretation of the film's ending as Bickle's dying dream. He admits that the last scene of Bickle glancing at an unseen object implies that Bickle will fall into rage and recklessness in the future and that he is like "a ticking time bomb".[47] Writer Paul Schrader confirms this in his commentary on the 30th-anniversary DVD, stating that Travis "is not cured by the movie's end," and that "he's not going to be a hero next time."[48] When asked on the website Reddit about the film's ending, Schrader said that it was not to be taken as a dream sequence but that he envisioned it as returning to the beginning of the film, as if the last frame "could be spliced to the first frame, and the movie started all over again."[49]

The film has also been associated with the 1970s wave of vigilante films, but it has also been set apart from them as a more reputable New Hollywood film. While it shares similarities with those films,[50] it is not explicitly a vigilante film and does not belong to that particular wave of cinema.[51]

The film can be seen as a spiritual successor to The Searchers, according to Roger Ebert. Both films focus on a solitary war veteran who tries to save a young girl who is resistant to his efforts. The main characters in both movies are portrayed as being disconnected from society and incapable of forming normal relationships with others. Although it is unclear whether Paul Schrader sought inspiration from The Searchers specifically, the similarities between the two films are evident.[52]

The film has been labeled as "neo-noir" by some critics,[53][54] while others have referred to it as an antihero film.[55][56] When shown on television, the ending credits featured a black screen with a disclaimer mentioning that "the distinction between hero and villain is sometimes a matter of interpretation or misinterpretation of facts." This disclaimer was thought to have been added after the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan in 1981, but in fact, it had been mentioned in a review of the film as early as 1979. LA Weekly, Letterboxd, and Yardbarker list this movie as belonging to the vetsploitation subgenre.[57][58][59]

Reception

Box office

The film opened at the Coronet Theater in New York City and grossed a house record of $68,000 in its first week.[60] It went on to gross $28.3 million in the United States,[61] making it the 17th-highest-grossing film of 1976.

Critical response

Taxi Driver received universal critical acclaim. Roger Ebert instantly praised it as one of the greatest films he had ever seen, claiming:

Taxi Driver is a hell, from the opening shot of a cab emerging from stygian clouds of steam to the climactic killing scene in which the camera finally looks straight down. Scorsese wanted to look away from Travis's rejection; we almost want to look away from his life. But he's there, all right, and he's suffering.[62]

On the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 89% based on 158 reviews and an average rating of 9.1/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "A must-see film for movie lovers, this Martin Scorsese masterpiece is as hard-hitting as it is compelling, with Robert De Niro at his best."[63] Metacritic gives the film a score of 94 out of 100, based on reviews from 23 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[64]

Taxi Driver was ranked by the American Film Institute as the 52nd-greatest American film on its AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) list, and Bickle was voted the 30th-greatest villain in a poll by the same organization. The Village Voice ranked Taxi Driver at number 33 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[65] Empire also ranked him 18th in its "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters" poll,[66] and the film ranks at No. 17 on the magazine's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time.[67]

Time Out magazine conducted a poll of the 100 greatest movies set in New York City. Taxi Driver topped the list, placing at No. 1.[68] Schrader's screenplay for the film was ranked the 43rd-greatest ever written by the Writers Guild of America.[69] Taxi Driver was also ranked as the 44th best-directed film of all time by the Directors Guild of America.[70] In contrast, Leonard Maltin gave a rating of only 2 stars and called it a "gory, cold-blooded story of a sick man's lurid descent into violence" that was "ugly and unredeeming".[71]

In 2012, in a Sight & Sound poll, Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi selected Taxi Driver as one of his 10 best films of all time.[72] Quentin Tarantino also listed the movie among his 10 greatest films of all time.[73]

Accolades

American Film Institute

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (1998) – #47

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills (2001) – #22

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Heroes & Villains (2003)

- Travis Bickle – #30 Villain

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes (2005)

- "You talkin' to me?" – #10

- AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores (2005) – Nominated[87]

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) (2007) – #52

Other honors

- National Film Registry – Inducted in 1994[88]

- The film was chosen by Time as one of the 100 best films of all time.[89]

- In 2015, Taxi Driver ranked 19th on BBC's "100 Greatest American Films" list, voted on by film critics from around the world.[90]

Legacy

Taxi Driver, American Gigolo, Light Sleeper, and The Walker make up a series referred to variously as the "Man in a Room" or "Night Worker" films. Screenwriter Paul Schrader (who directed the latter three films) has said that he considers the central characters of the four films to be one character, who has changed as he has aged.[91][92] The film also influenced the Charles Winkler film You Talkin' to Me?[93]

Although Meryl Streep had not aspired to become a film actor, De Niro's performance in Taxi Driver had a profound impact on her; she said to herself, "That's the kind of actor I want to be when I grow up."[94]

The 1994 portrayal of psychopath Albie Kinsella by Robert Carlyle in British television series Cracker was in part inspired by Travis Bickle, and Carlyle's performance has frequently been compared to De Niro's as a result.[95][96]

In the 2012 film Seven Psychopaths, psychotic Los Angeles actor Billy Bickle (Sam Rockwell) believes himself to be the illegitimate son of Travis Bickle.[97]

The vigilante ending inspired Jacques Audiard for his 2015 Palme d'Or-winning film Dheepan. The French director based the eponymous Tamil Tiger character on the one played by Robert De Niro in order to make him a "real movie hero".[98] The script of Joker by Todd Phillips also draws inspiration from Taxi Driver.[99][100][101]

"You talkin' to me?"

De Niro's "You talkin' to me?" speech has become a pop culture mainstay. In 2005, it was ranked number 10 on the American Film Institute's AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes.

In the relevant scene, the deranged Bickle is looking into a mirror at himself, imagining a confrontation that would give him a chance to draw his gun:

You talkin' to me? You talkin' to me? You talkin' to me? Then who the hell else are you talkin' to? You talkin' to me? Well I'm the only one here. Who the fuck do you think you're talking to?

While Scorsese said that he drew inspiration from John Huston's 1967 movie Reflections in a Golden Eye in a scene in which Marlon Brando's character is facing the mirror,[102] screenwriter Paul Schrader said De Niro improvised the dialogue and that De Niro's performance was inspired by "an underground New York comedian" he had once seen, possibly including his signature line.[103] Roger Ebert said of the latter part of the phrase "I'm the only one here" that it was "the truest line in the film.... Travis Bickle's desperate need to make some kind of contact somehow—to share or mimic the effortless social interaction he sees all around him, but does not participate in."[104] In his 2009 memoir, saxophonist Clarence Clemons said that De Niro explained the line's origins during production of New York, New York (1977), with the actor seeing Bruce Springsteen say the line onstage at a concert.[105] In the 2000 film The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle, De Niro went on to repeat the monologue with some alterations in the role of the character Fearless Leader.[106]

"Now back to Gene Krupa's syncopated style."

When Travis and Cybill Shepherd's character go to the film, they pass by a street drummer who says: "Now back to Gene Krupa's syncopated style!" This line was sampled in 1997 in Apollo Four Forty's song Krupa.[107]

Home media

The first Collector's Edition DVD, which was released in 1999, was packaged as a single-disc edition. It contained special features such as behind-the-scenes footage and several trailers, including one for Taxi Driver.

In 2006, a 30th-anniversary two-disc "Collector's Edition" DVD was released. The first disc contains the film itself, two audio commentaries (one by writer Schrader and the other by Professor Robert Kolker), and trailers. This edition also includes some of the special features from the earlier release on the second disc, as well as some newly produced documentary material.[108][109]

To commemorate the film's 35th anniversary, a Blu-ray was released on April 5, 2011. It includes the special features from the previous two-disc collector's edition, plus an audio commentary by Scorsese that was released in 1991 for the Criterion Collection, which was previously released on LaserDisc.[110]

As part of the Blu-ray production, Sony gave the film a full 4K digital restoration, which included scanning and cleaning the original negative (removing emulsion dirt and scratches). Colors were matched to director-approved prints under guidance from Scorsese and director of photography Michael Chapman. An all-new lossless DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 soundtrack was also created from the original stereo recordings by Scorsese's personal sound team.[111][112] The restored print premiered in February 2011 at the Berlin Film Festival. To promote the Blu-ray, Sony also had the print screened at AMC Theatres across the United States on March 19 and 22.[113][114][115]

Possible sequel and remake

In late January 2005, De Niro and Scorsese announced a sequel.[116] At a 25th-anniversary screening of Raging Bull, De Niro talked about the development of a story featuring an older Travis Bickle. In 2000, De Niro expressed interest in bringing back the character in a conversation with Actors Studio host James Lipton.[117] In November 2013, he revealed that Schrader had written a first draft, but both he and Scorsese thought it was not good enough to proceed.[118]

Schrader disputed this in a 2024 interview, saying, "Robert is the one who wanted to do that. He asked Marty and I. [...] So he pressed Marty on it and Marty asked me and I said, 'Marty, that’s the worst fucking idea I’ve ever heard.' He said, 'Yeah, but you tell him. Let’s have dinner.' So we had dinner at Bob’s restaurant and Bob was talking about it. I said, 'Wow, that’s the worst fucking idea I’ve ever heard. That character dies at the end of that movie or dies shortly thereafter. He’s gone. Oh, but maybe there is a version of him that I could do. Maybe he became Ted Kaczynski and maybe he’s in a cabin somewhere and just sitting there, making letter bombs. Now, that would be cool. That would be a nice Travis. He doesn’t have a cab anymore. He just sits there [Laughs] making letter bombs.' But Bob didn’t cotton to that idea, either."[119]

In 2010, Variety reported rumors that Lars von Trier, Scorsese, and De Niro planned to work on a remake of the film with the same restrictions used in The Five Obstructions.[120] However, in 2014, Paul Schrader said that the remake was not being made. He commented, "It was a terrible idea" and "in Marty's mind, it never was something that should be done."[121]

See also

- Martin Scorsese filmography

- 1976 in film

- List of cult films

- List of films set in New York City

- Crime in New York City

- History of the United States (1964–1980)

Notes

- ^ Posthumous nomination.

- ^ a b Posthumous award.

- ^ Posthumous nomination

References

- ^ a b c "AFI|Catalog - Taxi Driver". catalog.afi.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- ^ "Taxi Driver (18)". British Board of Film Classification. May 5, 2006. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- ^ a b F. Dick, Bernard (1992). Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio. University Press of Kentucky. p. 193. ISBN 9780813149615. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ Grist, Leighton (2000). The Films of Martin Scorsese, 1963–77: Authorship and Context. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 130. ISBN 9780230286146. Archived from the original on March 8, 2018. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ "Taxi Driver". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Archived from the original on February 1, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "Taxi Driver - Golden Globes". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

Robert De Niro stars as Travis Bickle in this oppressive psychodrama about a Vietnam veteran who rebels against the decadence and immorality of big city life in New York while working the nightshift as a taxi driver.

- ^ Mitchell, Neil (February 8, 2016). "Taxi Driver: 5 films that influenced Scorsese's masterpiece". British Film Institute. Retrieved August 5, 2024.

Forty years later, we look at some of the filmic influences on Martin Scorsese's brilliant psychodrama Taxi Driver.

- ^ Suarez, Carla (October 25, 2020). "Cult Series: Taxi Driver - Scorsese's legendary portrayal of a lone wolf's existential angst". STRAND Magazine. Archived from the original on May 14, 2023. Retrieved May 14, 2023.

- ^ "Taxi Driver (1976)". BFI. Archived from the original on December 29, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2018.

- ^ a b Wilson 2011, p. 51.

- ^ a b Thompson, David; Christie, Ian (1989). Scorsese on Scorsese. New York City: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. p. 63. ISBN 0571220029.

- ^ a b "The Untold Truth of Taxi Driver". September 20, 2022. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved June 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Rausch, Andrew J. (2010). The Films of Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro. Scarecrow Press. pp. 27–32. ISBN 978-0-8108-7413-8.

- ^ Thompson, Richard (March–April 1976). "Interview: Paul Schrader". Film Comment: 6–19. Archived from the original on June 14, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2022.

- ^ Taxi Driver (Two-Disc Collector's Edition) (DVD, Audio Commentary), Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, August 14, 2007

- ^ "Travis gave punks a hair of aggression." Toronto Star February 12, 2005: H02

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 50.

- ^ Thurman, John (April 5, 1976). "Citizen Bickle, or the Allusive Taxi Driver: Uses of Intertextuality". Sensesofcinema.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2024.

- ^ Dadds, Kimberley (December 10, 2017). "Hoffman turned down 'crazy' Scorsese". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on July 22, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2021.

- ^ "Taxi Driver". IMDb.

- ^ Rausch, Andrew J. (2010). The Films of Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro. Scarecrow Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780810874145.

- ^ Perkins, Will (March 18, 2017). "Dan Perri: A Career Retrospective". Art of the Title. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Mir, Shaun (September 5, 2011). "Taxi Driver". Art of the Title. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ D. Snider, Eric (February 8, 2016). "13 Surprising Facts About Taxi Driver On Its 45th Anniversary". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (April 7, 2016). "'Taxi Driver' Oral History: De Niro, Scorsese, Foster, Schrader Spill All on 40th Anniversary". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Hilary (April 22, 2016). "Tribeca: 'Taxi Driver' Team Recalls Filming in 1970s New York, Current Relevance of Classic". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge (April 1, 2015). "Martin Scorsese Remembers Shooting Taxi Driver in New York". Vulture. Archived from the original on March 30, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Bernard Hermann". CFBT-FM. Archived from the original on March 17, 2014. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ^ "Taxi Driver [Original Soundtrack]". AllMusic. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved October 27, 2016.

- ^ Wilson 2011, p. 57.

- ^ Smith, Steven C. (1991). A Heart at Fire's Center: The Life and Music of Bernard Herrmann (2002 reprint ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 350–352. ISBN 0-520-22939-8. Archived from the original on March 31, 2024. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Rabin, Nathan (February 9, 2010). "Week 27: Kris Kristofferson, Silver-Tongued Devil". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ^ "Jodie Foster recalls working with Robert De Niro and Martin Scorsese in Taxi Driver as a Kid". Vanity Fair. April 7, 2016. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2020.

- ^ "Jodie Foster details how 'uncomfortable' it was playing a prostitute aged 12 in Taxi Driver". Independent.co.uk. May 20, 2016. Archived from the original on February 26, 2019.

- ^ Keyser, Les (1992). Martin Scorsese. Twayne. p. 94. ISBN 0-8057-9315-1.

- ^ "Forty Years After "Taxi Driver," Jodie Foster Recalls the Making of a Classic". September 22, 2016. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019.

- ^ Woods, Paul A. (2005). Scorsese: a journey through the American psyche. Plexus. ISBN 0-85965-355-2.

- ^ "Hinckley Found Not Guilty, Insane". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 5, 2019.

- ^ "Hinckley, Jury Watch 'Taxi Driver' Film". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020.

- ^ j. d, Anjelica Cappellino (August 9, 2016). "The Trial of John Hinckley Jr. and Its Impact on Expert Testimony". Expert Institute. Archived from the original on February 15, 2019.

- ^ "Taxi Driver remains one of the best (and most troubling) of Palme winners". The A.V. Club. January 16, 2014. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019.

- ^ Taubin, Amy (March 28, 2000). Taxi Driver. British Film Institute. ISBN 0-85170-393-3.

- ^ "At Cannes, Le Booing Isn't Just Reserved for Bad Films". The New York Times. August 17, 2017. Archived from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2020.

- ^ "'Taxi Driver' Oral History: De Niro, Scorsese, Foster, Schrader Spill All on 40th Anniversary". The Hollywood Reporter. April 7, 2016. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018.

- ^ Great Movie: Taxi Driver Archived October 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine RogerEbert.com January 1, 2004. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ "ReelViews Movie Review". Reelviews.net. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Taxi Driver LaserDisc commentary

- ^ Taxi Driver audio commentary with Paul Schrader

- ^ Schrader, Paul (August 5, 2013). "I am Paul Schrader, writer of Taxi Driver, writer/director of American Gigolo and director of The Canyons. AMA!". Reddit. Archived from the original on January 31, 2014. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Lim, Dennis (October 19, 2009). "Vigilante films, an American tradition". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ Novak, Glenn D. (November 1987). "Social Ills and the One-Man Solution: Depictions of Evil in the Vigilante Film" (PDF). International Conference on the Expressions of Evil in Literature and the Visual Arts. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ebert, Roger. "Taxi Driver Movie Review & Film Summary (1976) | Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2018. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Film site Movie Review: Taxi Driver (1976)". filmsite.org. AMC. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ Schwartz, Ronald (January 1, 2005). Neo-noir: The New Film Noir Style from Psycho to Collateral. Scarecrow Press. p. 33. ISBN 9780810856769. Archived from the original on December 3, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ Bouzereau, Laurent (Writer, Director, and Producer) (1999). Making Taxi Driver (Television production). United States: Columbia TriStar Home Video. 102 minutes in.

The best movies that I know of are the seventies', precisely because I think people were really ... interested by the antihero, which has pretty much gone away now. ... I do think that it would be a movie that it would be very difficult to finance nowadays.

- ^ "De Niro takes anti-hero honours". BBC News. August 16, 2004. Archived from the original on November 14, 2017. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ^ Sweeney, Sean (May 25, 2018). "10 VETSPLOITATION MOVIES TO WATCH OVER MEMORIAL DAY WEEKEND". LA Weekly. Semanal Media LLC. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved February 4, 2024.

- ^ "Vetsploitation. List by Jarrett". Letterboxd. 2018. Archived from the original on February 4, 2024. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Jeremy (June 10, 2020). "Vietnam War movies, ranked. 11. "Rolling Thunder"". Yardbarker. Archived from the original on March 9, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

Vetsploitation was a viable Hollywood genre in the late '70s and throughout much of the '80s. "First Blood," "The Exterminator," "Thou Shalt Not Kill… Except"… even "Taxi Driver" to a degree.

- ^ "Taxi Driver Is Sensational". Variety. February 18, 1976. p. 24.

- ^ Taxi Driver Archived February 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Box Office Mojo Internet Movie Database. Retrieved March 31, 2007

- ^ "Taxi Driver". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 25, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ "Taxi Driver". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on October 1, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ "Taxi Driver". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Archived from the original on March 11, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ "Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on August 26, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2006.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters". Empire. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2008.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire. October 3, 2008. Archived from the original on August 22, 2016. Retrieved April 9, 2016.

- ^ "The 101 best New York movies of all time". Time Out. June 17, 2016. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved May 29, 2016.

- ^ "101 Greatest Screenplays". Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on February 6, 2017. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ The 80 Best-Directed Films Directors Guild of America. Retrieved April 12, 2024.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2013). Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide The Modern Era. New York: Penguin Group. p. 1385. ISBN 978-0-451-41810-4.

- ^ "Asghar Farhadi's Top 10 Director's Poll". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Quentin Tarantino's handwritten list of the 11 greatest films of all time". Far Out Magazine. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ "The 49th Academy Awards (1977) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "Film in 1977". British Academy Film Awards. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "Taxi Driver". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "29th Annual DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Taxi Driver". Golden Globe Awards. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "19th Annual GRAMMY Awards". Grammy Awards. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1970-79". Kansas City Film Critics Circle. December 14, 2013. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ "2nd Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on September 4, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Films Selected to The National Film Registry, Library of Congress, 1989–2005 Archived April 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 10, 2007.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. December 19, 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Film Hall of Fame: Productions". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ "Film Hall of Fame: Characters". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved November 27, 2024.

- ^ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America Awards. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores: Honoring America’s Greatest Film Music, Official Ballot American Film Institute via Internet Archive. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2020.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (January 23, 2012). "The Complete List – ALL-TIME 100 Movies". Time. Archived from the original on March 14, 2007. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "100 Greatest American Films". BBC. July 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Interview with Paul Schrader Archived June 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, BBC Radio 4's Film Programme, August 10, 2007

- ^ "Filmmaker Magazine, Fall 1992". Filmmakermagazine.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ James, Caryn (2012). "New York Times film overview". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ Longworth, Karina (2013). Meryl Streep: Anatomy of an Actor. Phaidon Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7148-6669-7. Archived from the original on February 9, 2024. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ McKay, Alastair (August 13, 2005). "To be and to pretend". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 18, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2019.

- ^ "Pain, with no jokes taken out". The Independent. September 16, 1995. Archived from the original on October 13, 2019. Retrieved October 13, 2019.

- ^ Shone, Tom (December 3, 2012). "Sam Rockwell: Hollywood's odd man out". Archived from the original on August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 3, 2014.

- ^ Trio, Lieven (August 25, 2015). "Jacques Audiard dévoile 'Dheepan', sa palme d'or". Metro. Archived from the original on August 26, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ^ Kohn, Eric (April 3, 2019). "'Joker': Robert De Niro Addresses the Connection Between His Character and 'King of Comedy'". IndieWire. Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved August 28, 2019.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (August 22, 2017). "The Joker Origin Story On Deck: Todd Phillips, Scott Silver, Martin Scorsese Aboard WB/DC Film". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "The Making of Joker". Closer Magazine Movie Special Edition. 19 (65). American Media, Inc.: 8–19. 2019. ISSN 1537-663X.

- ^ Taubin, Amy (2000). Taxi Driver. London: BFI Publishing. ISBN 0-85170-393-3.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (February 15, 1976). "Scorsese's Disturbing 'Taxi Driver'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 1, 1996). "Taxi Driver: 20th Anniversary Edition". RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Clemons, Clarence (2009). Big Man: Real Life & Tall Tales. Sphere. ISBN 978-0-7515-4346-9.

- ^ "Robert De Niro's Best, Worst and Craziest Performances". rollingstone.com. September 24, 2015. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved February 28, 2020.

- ^ "Taxi Driver Drummer Trivia". February 25, 2018.

- ^ Taxi Driver, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment, August 14, 2007, archived from the original on November 14, 2020, retrieved February 15, 2019

- ^ Tobias, Scott (August 11, 2007). "Taxi Driver: Collector's Edition". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ Taxi Driver Blu-ray, archived from the original on February 16, 2019, retrieved February 15, 2019

- ^ "Home Cinema @ The Digital Fix – Taxi Driver 35th AE (US BD) in April". Homecinema.thedigitalfix.co.uk. Archived from the original on February 19, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- ^ "From Berlin: 4K 'Taxi Driver' World Premiere". MSN. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011.

- ^ Meza, Ed (January 27, 2011). "Restored 'Taxi Driver' to preem in Berlin". Variety. Archived from the original on February 15, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ "Berlinale 2011: Taxi Driver". Park Circus. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ "Scorsese's 'Taxi Driver' is Returning to AMC Theatres for Two Days". FirstShowing.net. March 3, 2011. Archived from the original on February 16, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (February 5, 2005). "Scorsese and De Niro plan Taxi Driver sequel". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ Saravia, Jerry. "Taxi Driver 2: Bringing Out Travis". faustus. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (November 14, 2013). "Robert De Niro: 'I'd like to see where Travis Bickle is today'". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on November 24, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

- ^ Newman, Nick (May 20, 2024). "Paul Schrader on 'Oh, Canada,' Tarantino's 'The Movie Critic,' and the 'Worst F**king Idea' of a 'Taxi Driver' Sequel". Indiewire.

- ^ Steve Barton (February 16, 2010). "Lars von Trier, Robert De Niro, and Martin Scorsese Collaborating on New Taxi Driver". Dread Central. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2010.

- ^ Selcke, Dan (February 19, 2014). "Taxi Driver will not be remade by Lars Von Trier, if anyone was worried". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on August 18, 2016. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

Works cited

- Wilson, Michael (2011). Scorsese On Scorsese. Cahiers du Cinéma. ISBN 9782866427023.