Tarro, New South Wales

| Tarro Newcastle, New South Wales | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tarro General store reopened 2010 | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 32°48′32″S 151°39′22″E / 32.80889°S 151.65611°E | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 1,703 (SAL 2021)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| • Density | 1,948/km2 (5,050/sq mi) Note1 | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 2322 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 10 m (33 ft) | ||||||||||||||

| Area | 6 km2 (2.3 sq mi)Note2 | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | AEST (UTC+10) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | AEDT (UTC+11) | ||||||||||||||

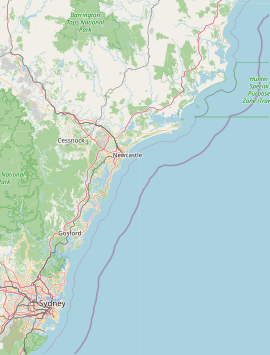

| Location |

| ||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | |||||||||||||||

| Region | Hunter[2] | ||||||||||||||

| County | Northumberland[3] | ||||||||||||||

| Parish | Alnwick[3] | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Wallsend[4] | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Paterson | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Tarro (/tæroʊ/) is a north-western suburb of the Newcastle City Council local government area in the Hunter Region of New South Wales, Australia.[2][3] It, and parts of nearby Beresfield, was originally known as Upper Hexham, "lower" Hexham being an older settlement located about 5 kilometres (3 mi) to the east on the Hunter River. The name "Tarro" reportedly means "stone" in an Aboriginal language.[5]

At the 2006 census, Tarro had a population of 1,558, almost all of which is concentrated in the south-western corner of the suburb.[6][7]

Geography

Tarro and the adjacent suburbs of Beresfield, Woodberry and Thornton are situated on low ridges rising out of the surrounding floodplain (and wetlands) of the Hunter River.

Early Tarro compromised a number of scattered farms which made use of the surrounding wetlands. Housing was otherwise strung out along Maitland Road (then the New England Highway, now Anderson Drive) between the railway station in the east to what was to become Beresfield in the west. After World War II, Tarro became increasingly suburban. The area bounded by Eastern, Western and Southern Avenues was subdivided. This was followed by land between Christie Road and Maitland Road, then in the late 1960s-1970s land between Western Avenue and Christie Road and then behind the Tarro Hotel. In mid-1980s land between Christie Road and Beresfield was sold off to L.J Hooker, then known as Hooker Homes, where more residential homes were built, all following the same basic design.[citation needed]

Modern Tarro includes a 3.4 km (2.1 mi) section of the Hunter River, located in the eastern and southeastern parts of the suburb. The suburb extends along the Hunter River in the southeast to the Hexham bridges, where it meets the suburb of Kooragang. Despite their name, the Hexham bridges are actually located in Tarro, the southbound bridge forming the border between Tarro and Kooragang. The southern and northern approaches to the bridges, on the Pacific Highway, are in Hexham and Tomago respectively.[7]

History

Indigenous past

The area where Tarro is located originally was part of the territory of the Pambalong clan of the Awabakal people. The land of the Pambalong stretched from Newcastle West, extended along the southern bank of the Hunter River, west through Hexham (Tarro) to Buttai and across to the foothills of Keeba-Keeba (Mount Sugarloaf) to the northern tip of Lake Macquarie and back to Newcastle West. The country of the Pambalong was known as Barrahineban.[8]

Churches

In 1841 Edward Sparke Snr, original settler and owner of "Woodlands" conveyed 2.43 hectares (6 acres) of land on the High Road to the Church of England and the Bishop of Australia. During the same year he donated 0.4 ha (1 acre) to the Lord Bishop of Australia, William Grant Broughton, for a burial ground. In 1842 Sparke and his wife Mary, with the approval of Robert Scott the mortgagee, sold Bishop Broughton 1.6 ha (4 acres) four acres "on which a Parsonage House is now built", commencing at the north east corner of the Township of Upper Hexham, for £100, "for erection and completion of Parsonage".[9]

A church, named St Stephens, was opened in Tarro around 1849. This rustic structure, was replaced by a more elegant wooden building in 1905. There was also a parsonage. This church was later joined by Sunday school hall in the 1960s. Next door was tennis court, which was later replaced by a youth centre in the early 1970s. Around 1980 St Stephens was sold and removed. The site of the church is now the site of the Tarro Interchange with the New England Highway.

Tarro's old pioneer cemetery is on Quarter Sessions Road with burials dating from the mid nineteenth century.[10]

The foundation stone for Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church at 42 Anderson Drive was laid on 4 December 1922.[11]

Post office

Tarro's first post office was named Upper Hexham and was located at the railway station. Around 1918 the post office moved to Woodberry Road, and later to 13 Maitland Road (now Anderson Drive). The post office housed the manual telephone switchboard until automatic switching was introduced in 1957. The post office closed on 30 July 1993 and Tarro is now served by Beresfield Post Office.

Railway

Tarro has a railway station, which opened in 1857 with the Newcastle-Maitland railway - the first section of the Main North line from Sydney to the New England region.[12] The station is one of the oldest in Australia, being the original eastern terminus for the Hunter Valley Railway before it was extended to Newcastle. It was originally known as Hexham when it opened in 1857. In 1871 the name was changed to Hexham Township and then Tarro.[13] The station is now served by NSW TrainLink's Hunter line.

The railway station was once quite large with a timber and glazed station master's office and signal room as well as brick ticket offices and waiting rooms on the Maitland-bound platform and a smaller timber ticket office and waiting room on the Newcastle-bound platform.[14] After suffering vandalism in the 1970s, these buildings were demolished and replaced by simple weathersheds. At one time there were loading ramps to the west of the railway station and roadbridge which were used to load coal in the 1940s from a small mine, Kent Colliery, at Beresfield. Some evidence of these ramps still remains.

Demographics

According to the 2016 Census[15] the median age in Tarro is 45. The population of the suburb is 1,645, a slight increase from 1,641 in 2011. 5.1% of residents are Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander with the median age among this group being 19. Tarro has a higher proportion (24.4%) of residents aged 65+ than the national average (15.8%).

86.3% of residents report being born in Australia; significantly higher than the national average of 66.7%. The most common other countries of birth are England (2.5%), New Zealand (0.9%) and Taiwan (0.8%). The most common reported ancestries in Tarro are English, Australian and Irish. 75.2% of residents reported having both parents born in Australia; considerably higher than the national average of 47.3%.

The top religious groups in Tarro are Anglican 28.6%, Catholic 20.5% and Uniting Church 6.7%. 24.7% stated no religion and 8.7% did not answer the question.

Education

The first school in Tarro was held in the home of the Anglican Reverend Bolton in 1844. Around 1860, a school house was opened, opposite St Stephens' Church, on the northern side of Maitland Road.[16]

A Government operated public school opened in Upper Hexham in 1881. This eventually became Beresfield Public School. The original schoolhouse is now in the grounds of Beresfield Public School at 181 Anderson Drive. The schoolhouse is now heritage listed.[17] A second public primary school was built in Tarro proper, opening in 1961. Tarro also has a Catholic primary school, adjoining Our Lady of Lourdes Catholic Church.

The nearest public secondary school is Francis Greenway High School at Beresfield. The high school is named after convict architect Francis Greenway who was granted land in the Tarro area around 1820.[18]

Other facilities

Tarro has a petrol station, butcher's shop, and motel/mobile home village. The Tarro Hotel closed in July 2015 and was demolished soon after. The local newsagent/general store has also closed as of 2024. There is also a fire station, community hall, Telstra telephone exchange, pumping station and depot belonging to the Hunter Water Corporation, electricity sub-station and a number of small churches. The pumping station is heritage listed.[19] Tarro Park sports ground, largely reclaimed from wetlands, has several soccer and football fields, a playground and bird ponds. Tarro's second smaller park, opposite the community hall on Northern avenue was resumed by the catholic school in the 2000s and fenced to prevent public access.

Police station

Tarro previously had a police station which closed in 1976, with the area then to be served from Beresfield police station. The Beresfield police station currently operates on a part-time basis with the main coverage of the area being provided from Maitland Police station.

War memorial

Following World War I, Tarro and the nearby community of Woodberry established a memorial to veterans. The memorial was unveiled by Lieutenant Colonel Charles Nicholson, Member for Maitland, on behalf of Woodberry and Tarro residents about 1920. The memorial lists 14 veterans, including five killed in action The memorial was relocated & rededicated by D J Shearman in December 1974. The memorial can now be seen at the Fred Harvey Oval, Lawson Avenue, Woodberry.[20]

Image gallery

- Tarro telephone exchange

- Tarro Hotel

- Tarro Fire Station

Notes

- ^ Most of Tarro is unpopulated with almost all of the population residing in the south-western corner of the suburb. The population density figure provided is the average density of the part of the suburb where most of the population lives, not the average for the whole area which is considerably lower at 259.7/km2 (673/sq mi). This lower figure does not accurately represent the population density in the suburb.

- ^ Area calculation is based on 1:100000 map 9232 NEWCASTLE.

References

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Tarro (suburb and locality)". Australian Census 2021 QuickStats. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ^ a b c "Suburb Search - Local Council Boundaries - Hunter (HT) - Newcastle". New South Wales Division of Local Government. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ a b c "Tarro". Geographical Names Register (GNR) of NSW. Geographical Names Board of New South Wales. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Wallsend". New South Wales Electoral Commission. 28 March 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ "Place names, origins and meanings". Newcastle City Council. Retrieved 17 October 2008.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (25 October 2007). "Tarro (State Suburb)". 2006 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 18 October 2008. Map

- ^ a b "Tarro". Land and Property Management Authority - Spatial Information eXchange. New South Wales Land and Property Information. Retrieved 14 May 2008.

- ^ Maynard, John. Whose Traditional Land?: The Pambalong or Big Swamp People Barahineban (PDF) (Technical report). The University of Newcastle. pp. 27–37. Retrieved 6 June 2014.

- ^ Hartley, Dulcie, "Men of Their Time - Pioneers of The Hunter River" page 21 ISBN 0-646-25218-6 [1995]

- ^ "Search Results". Newcastle City Council. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Our Lady of Lourdes Church". NSW Heritage Branch. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Main North Line". nswrail.net. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Tarro Station". nswrail.net. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Tarro Railway Station (NSW)". State Records NSW. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "2016 Census QuickStats: Tarro". censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Orchard, Gail, God's Acre: Religion Comes to the Bend in the River, p. 14

- ^ "Beresfield Public School". NSW Heritage Branch. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Unmarked Grave of our First Lighthouse Designer". Lighthouse.net. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Pumping Station". NSW Heritage Branch. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Woodberry - Tarro War Memorial". Register of War Memorials in NSW. New South Wales Government. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2008.